A stock market is a market for the trading of company stock, and derivatives of same; both of these are securities listed on a stock exchange as well as those only traded privately.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stock_market

How Stocks and the Stock Market Work

http://money.howstuffworks.com/stock.htm

US Markets

http://money.cnn.com/data/us_markets/

Virtual Stock Exchange

http://vse.marketwatch.com/Game/Homepage.aspx

Map of the Market

http://www.smartmoney.com/marketmap/

Stock Market Quotes

http://www.marketwatch.com/

The history of the stock market begins back in the 11th century in Cairo, Egypt. It is believed that during this period of time Jewish and Islamic merchants established a trade association that incorporated most of what we consider modern day credit and payment methods. By the 12th century agricultural debts were managed and regulated by French courratier de change. The courratier de change could technically be considered the first “stock brokers” because they not only managed debt and payments, but they also traded in debt products. Another century passed and the development of the modern stock market continued. At his point merchants and financiers in Venice added governmental securities to traded debts and investments. Many other major cities soon followed this example and began to trade in their own government securities. The first official stocks and bonds to be issued and traded were for the Dutch East India Company and they were traded on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange in 1602.

Today there are several stock exchanges in just about every developed country. Each of these exchanges has its own listing of stocks and bonds that it trades, and each is subject to its own economic cycle. These cycles include periods of growth, staleness and recessions. The health of each stock market will depend on the health of local economies, national economies, and in some cases international economies. Before you select a stock market to use for your investment activities make sure that you understand the types of investments that it offers, and make sure that you understand the investment rules, policies and procedures for that stock market.

http://ezinearticles.com/?The-Stock-Market-Timeline&id=414225

Stock Exchanges

A stock exchange is a forum for trading in securities representing shares of firms. An exchange provides ways by which financing is raised by the sale of shares to outside investors. It provides a mechanism for the valuation of companies through the process of price discovery and a means by which such information is disseminated.

A formal definition of the term exchange is a critical component of law and regulation regarding securities trading markets, discussed by Domowitz (1996) and Lee (1998). In the United States, the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) is legally an exchange, while the markets operated by the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASDAQ) and Instinet, an electronic communications network (ECN), are not. All three examples nevertheless satisfy the definition of a stock exchange given above. Given differences across countries with respect to legal definitions, a more unified approach is needed to focus the discussion.

The approach taken here is to identify important attributes and functions of institutions satisfying the basic definition in practice. Exchanges provide trading systems and may offer more than one. Types of trading systems are sometimes differentiated by the form of market intermediation provided by entities with direct access to the system. The nature of competition between exchanges is a defining feature, since exchanges may adopt varying market structures in order to compete in different fashions. A stock exchange is a business entity, and the form of its governance arrangements is important in understanding its nature and conduct.

Trading Systems

Trading markets may be defined as systems consisting of an order routing system, an information network, and a trade execution mechanism (Stoll, 1992). A trading system is a communications technology for passing allowable messages between traders, together with a set of rules that transform traders' messages into transactions prices and allocations of quantities of stock among market participants.

The nature of allowable messages varies with the exchange's rules and technology. A typical message consists of an offer to buy, or to sell, a given number of shares at a certain price. The NYSE, for example, permits such messages, as well as orders, to buy some amount of stock at current market prices. The OptiMark system of the Pacific Stock Exchange also allows traders to submit a message indicating the strength of the traders' desire to transact an amount of stock at a particular price. Orders for the shares of a company, contingent on the completion of transactions in other companies, are possible. As technology advances, the ability of trading systems to offer more flexible messages increases.

The transformation of messages and information from the system into a price and a set of quantity allocations is governed by another set of rules. In open outcry auctions, bids and offers are orally exchanged by traders standing in a single physical location. The acceptance of a bid or offer by another trader generates a transaction. In dealer systems, such as NASDAQ, dealers accept orders by telephone or computerized routing, and transact at prices they themselves set. In batch auctions, such as that of the Arizona Stock Exchange, price is set by maximizing trading volume, given order submission at the time of the auction. In most computerized markets, traders submit orders to a central limit order book, and a mathematical algorithm determines prices and quantities. Examples include the CAC system of the Paris Bourse and the OMsystem of the Stockholm Stock Exchange. The range of possibilities here is large, and a taxonomy of rules is given in Domowitz (1993).

Market Intermediation

Investors are generally not given free access to trading systems. Entry into the exchange's systems is intermediated by brokers. Brokers may simply route orders to exchanges. They sometimes make decisions as to what exchange, and what system within the exchange, should process various parts of an order. In open outcry markets, brokers also physically represent orders on the floor of the exchange.

Exchanges are differentiated most by a class of intermediaries known as market makers. Market makers trade for their own accounts, usually providing an offer to sell and an offer to buy at the same time, but at different prices. In doing so, they both contribute to the pricing process and supply immediacy to the market by a willingness to be a counterparty to an order for which another investor may not be immediately available.

On some exchanges, most notably the NYSE, there is one primary market maker designated by the exchange, known as the specialist. The specialist obtains consideration for the supply of immediacy and the maintenance of an orderly market by having private access to order-flow information through the order book for the stock.

There may be multiple market makers in a given stock, regardless of the precise form of trading system. The prototype example is that of dealer markets, in which the dealers are the market makers. They post bids and offers, and trade out of their own inventory.

Electronic limit order book markets offer the possibility of trading without such financial intermediation. In practice, however, market makers exist on electronic markets as well. Multiple market makers in a security are often designated by an exchange, fulfill obligations not dissimilar to those of a specialist, and receive some consideration for the service. Anyone with direct access to the trading system can function as a market maker, however, simply by continuously offering quotes for stock on both sides of the market.

Competition

Exchanges have two clienteles: companies, which list their shares, and investors, who trade on the exchange. Historically, the product (a listing) offered to companies was a bundle, consisting of(1) liquidity, (2) monitoring of trading against forms of fraud, (3) standard-form rules of trading, (4) a signal that a listing firm's stock is of high quality, and (5) a clearing function to ensure timely payment and delivery of shares (Macey and O'Hara, 1999). The product offered to investors consists of a combination of liquidity and pricing information, as well as any benefits accruing to the investor from the bundle offered to companies.

Government regulation and increased competition from automated trading systems lessen the importance of exchange monitoring and standardized rules. Technological advances in information processing allow better signals about company quality than simple listings, permit wide distribution of pricing information outside exchanges, and enable separation of the clearing function from other exchange operations. The result is that exchanges now compete solely along the dimensions of liquidity and cost of trading (Domowitz and Stell, 1999; Macey and O'Hara 1999).

Competition through liquidity and cost has led to increased automation of the exchange trade execution process. Automated exchanges are less costly to build and operate, and provide lower-cost trade execution. Liquidity is enhanced by the ability to establish wide networks of traders through communications systems with an automated execution system at the nexus. The drive for increased liquidity through computerization has led to new developments in the structure of the exchange services industry, most notably including mergers and alliances between automated exchanges for increased order flow.

Communications technology and the computerization of trade execution have also globalized trading. The physical location and boundaries of an exchange floor are no longer important to traders. A company does not need to be listed, or even traded, on a domestic exchange. Not only are there many possible execution services providers, but electronic exchanges place their own terminals on foreign soil, allowing direct access to overseas listings, regardless of the nationality of the companies involved. An example is the U.K. electronic exchange, Tradepoint, which conducts operations in the United States.

Governance

Exchanges historically have been organized as not-for-profit membership cooperatives. Exchange governance is shifting to a for-profit corporate structure. Ten such demutualizations globally are listed in Domowitz and Stell (1999), and such initiatives are under investigation by many traditional exchanges, including NASDAQ and the NYSE. Three rationales for this change have been proposed.

Increased competition between exchanges forces the change in ownership structure (Hart and Moore, 1996). This is the view of the exchange services industry, as well. The industry argument is simply that a corporate structure with a profit motive enables faster initiatives in response to competitive advances than a committee-and voting-oriented membership organization.

Changes in the contractual relationship between exchanges and listing companies might outweigh competition as a force behind the shift from cooperative to corporate ownership arrangements (Macey and O'Hara, 1999). The long-term mutual dependency between companies and exchanges no longer exists, and market makers do not make firm-specific investments that might be fostered under a cooperative umbrella.

The third view is that communications and computerized execution technology permit and encourage the change in governance structure (Domowitz and Stell, 1999). Traditional ex changes are limited by floor space, and access is rationed through the sale of limited memberships. In an automated auction, there are no barriers to providing unlimited direct access, with a transactions-fee pricing structure, which in turn lends itself to corporate for-profit operations. All examples of the change in governance begin with a conversion from floor trading technology to automated trade execution. For trade execution services with no prior history of cooperative governance structure, the mutual structure is routinely avoided in favor of a for-profit joint-stock corporation.

http://www.answers.com/topic/stock-exchange?cat=biz-fin

Stock Market History

Here we have the stock market history for the stock market is the 20th century. In the 20th century the stock market has returned to investors an average

of 10.4% a year.

http://www.bullinvestors.com/Stock_Market_History.htm

Stock Market History: What—and Where is Wall Street?

http://www.stocks-investing.com/stock-market-history.html

Wall Street is in New York City, and has been, in fact, since 1644, when the inhabitants of Manhattan built a wall across Manhattan Island to keep the marauding British at bay. In one way or another, Wall Street has been protecting Manhattan against invaders ever since.

In the early days of the country, Boston, MA was the major shipping center and the national center of commerce, with commodities and bonds financing the growth of the young economy. In the late 1700s, Wall Street was the center point of commerce in New York City, but as yet did not have a defined place indoor for transacting financial business. Merchants sold shares to their friends and associates out of their warehouses or places of business. In 1792, where Battery Park now stands, two dozen leaders of the financial community created the first stock exchange, called the Stock Exchange Office. The SEO became the New York Stock Exchange in 1863. There are other, smaller stock exchanges in other cities such as Chicago, but the NYSE is the most widely-known.

The second most widely-known exchange also began in New York as the Curbstone Brokers. Because the NYSE had minimum limits set on the number of shares companies had to sell in order to qualify for auction, the Curbstone Brokers sold shares for companies that were too small to meet the 100-share minimum required by the larger organization. The Curbstone Brokers met and auctioned shares for a century before taking their outdoor auction indoors. In 1953, this hardy organization became the American Stock Exchange, which still operates today.

Wall Street & Stock Market History

http://www.atozinvestments.com/history-of-wall-street.html

Once upon a time, before New York City was a city, there really was a wall. It was built in 1644, on the lower end of Manhattan "Island" by the Dutch to protect against British attacks. Years later, the defensive wall was gone, but the road alongside remained and was, of course, called Wall Street. We think of Wall Street as the financial center of the world, but it hasn't always been this way.

Early in our country's history, Boston was the financial center of America. Bonds for projects such as roads, canals and bridges, and contracts for commodities such as hides and molasses, were bought and sold mostly by Boston dealers. However, there was not yet an official place to conduct such business.

Other countries had such "exchanges" for many years. Belgium established the world's first in 1531. Amsterdam soon followed, with brokers conducting their activity on a street called Warmoesstraat. In 1602, under the Amstel bridge, shares of the East India Company were bought and sold. Money was raised here to finance the Pilgrim's trip to America.

At this time, Paris conducted their financial business on Rue de Quincampoix.. In the early 1600's, Berlin's traders and merchants conducted their business at the Grotte in Schlossgarten.

London's stock exchange began as an outdoor market centered on Exchange Alley. By 1725, many London brokers began doing business at Jonathon's Coffee House which was renamed "The Stock Exchange" in 1773. An advertisement of the time by a broker named John Taylor proclaimed "Buyeth and selleth new lottery tickets, Navy victualling bills, East India bonds, and other publick securities".

It was just a matter of time before our new country, The United States of America, would organize formal stock and bond trading. 1792 was the year. In 1792, New York City's population was about 34,000, not including Brooklyn and Queens which were still separate towns. Much of Manhattan had just been rebuilt with brick buildings after the devastating Great Fire of 1776.

Wall Street was New York's center of commerce. Just a few blocks long, from Broadway on the west to the East River at the other end, Wall Street was not yet paved or even lined with cobblestones. There were warehouses for furs, coffee and tea, and other goods from all over the world. To the south, streets were crowded with slaughter houses and tanneries.

Wealthy businessmen, along with their ordinary trade, would sell lottery tickets, bonds, and shares of stocks in new banks that were forming. The hottest trading and speculating, was in treasury bonds issued by the new Bank of the United States.

Until 1792, a person wishing to buy or sell an investment would either advertise, or spread the word among associates and friends. Some of the first merchants to keep a supply of stock shares on hand were Leonard Bleeker at 16 Wall Street and Sutton & Harry at 20 Wall. On one day in 1791, 100 shares actually changed hands. Imagine that!

The first organized stock exchange was created in 1792, when under a buttonwood tree in Castle Garden (now called Battery Park), John Sutton, Benjamin Jay, and 22 other financial leaders signed an agreement of rules, regulations and fees.

Then in a building at 22 Wall Street, securities were auctioned every day beginning at noon, sold to the highest bidder. The seller paid the exchange a commission on each stock or bond sold.

They originally called this organization The Stock Exchange Office. This was a very exclusive organization, allowing only the elite of New York's financial community to join. And certainly no women were allowed! In just recent years, Muriel Siebert became the first female member of the New York Stock Exchange.

Stock Market and Wall Street History

http://www.atozinvestments.com/stockmarkethistory.html

Worst Stock Market Crashes

http://mutualfunds.about.com/cs/history/a/marketcrash.htm

WALL STREET HISTORY

Wall Street Crash of 1929

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wall_Street_Crash_of_1929

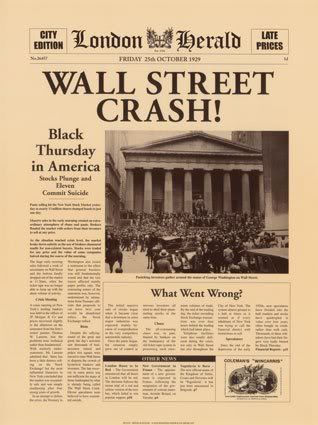

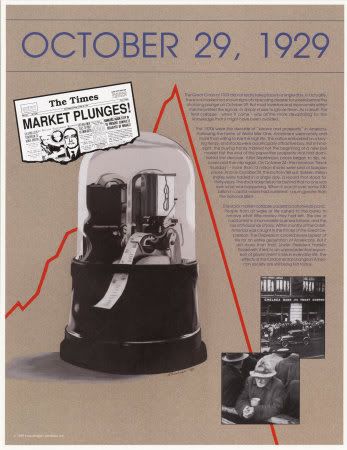

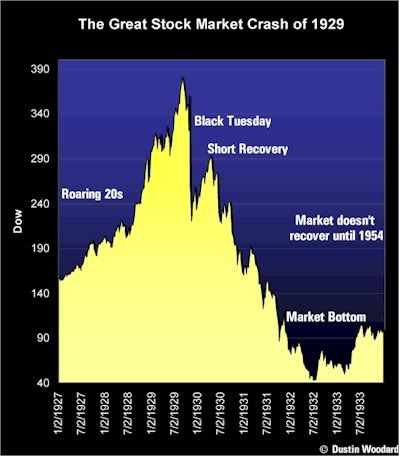

Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Crash of ’29, was one of the most devastating stock market crashes in American history. It consists of Black Thursday, the initial crash and Black Tuesday, the crash that caused general panic five days later. The crash marked the beginning of widespread and long-lasting consequences for the United States. Though economists and historians disagree on exactly what role the crash had in the subsequent economic fallout, some regard it as the start of the Great Depression. Most historians, however, agree that it was actually a symptom of the Great Depression, rather than a cause. The crash was also the starting point of important financial reforms and trading regulations.

At the time of the crash, New York City had grown to be a major financial capital and metropolis. The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) was the largest stock market in the world. The roaring twenties were a time of prosperity and excess in the city, and, despite warnings of speculation, many believed that the market could sustain high price levels. In the words of Irving Fisher, "Stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau."[1] The euphoria and financial gains of that great bull market were shattered on October 24, 1929, Black Thursday, when share prices on the NYSE collapsed. Stock prices fell on that day and they continued to fall, at an unprecedented rate, for a full month.

In days leading up to Black Thursday the market was unstable. Periods of panic selling and high volumes of trading were interspersed with brief periods of rising prices and recovery. After the crash the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) recovered early in 1930, only to reverse again, reaching a low point of the great bear market in 1932. The market did not return to pre-1929 levels until late 1954,[2] and was lower at its July 8, 1932 level than it had been since the 1800s.[3]

“ Anyone who bought stocks in mid-1929 and held on to them saw most of his adult life pass by before getting back to even.

Stock Market Crash

http://www.pbs.org/fmc/timeline/estockmktcrash.htm

1929 - The stock market crash ushered in the Great Depression.

What made the stock market crash? Here's a brief summary.

Capital is the tools needed to produce things of value out of raw materials. Buildings and machines are common examples of capital. A factory is a building with machines for making valued goods. Throughout the twentieth century, most of the capital in the United States was represented by stocks. A corporation owned capital. Ownership of the corporation in turn took the form of shares of stock. Each share of stock represented a proportionate share of the corporation. The stocks were bought and sold on stock exchanges, of which the most important was the New York Stock Exchange located on Wall Street in Manhattan.

Throughout the 1920s a long boom took stock prices to peaks never before seen. From 1920 to 1929 stocks more than quadrupled in value. Many investors became convinced that stocks were a sure thing and borrowed heavily to invest more money in the market.

But in 1929, the bubble burst and stocks started down an even more precipitous cliff. In 1932 and 1933, they hit bottom, down about 80% from their highs in the late 1920s. This had sharp effects on the economy. Demand for goods declined because people felt poor because of their losses in the stock market. New investment could not be financed through the sale of stock, because no one would buy the new stock.

But perhaps the most important effect was chaos in the banking system as banks tried to collect on loans made to stockmarket investors whose holdings were now worth little or nothing at all. Worse, many banks had themselves invested depositors' money in the stockmarket. When word spread that banks' assets contained huge uncollectable loans and almost worthless stock certificates, depositors rushed to withdraw their savings. Unable to raise fresh funds from the Federal Reserve System, banks began failing by the hundreds in 1932 and 1933.

By the inauguration of Franklin D. Roosevelt as president in March 1933, the banking system of the United States had largely ceased to function. Depositors had seen $140 billion disappear when their banks failed. Businesses could not get credit for inventory. Checks could not be used for payments because no one knew which checks were worthless and which were sound.

Roosevelt closed all the banks in the United States for three days - a "bank holiday." Some banks were then cautiously re-opened with strict limits on withdrawals. Eventually, confidence returned to the system and banks were able to perform their economic function again. To prevent similar disasters, the federal government set up the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which eliminated the rationale for bank "runs" - to get one's money before the bank "runs out." Backed by the FDIC, the bank could fail and go out of business, but then the government would reimburse depositors. Another crucial mechanism insulated commercial banks from stock market panics by banning banks from investing depositors' money in stocks.

The Great Depression

The Crash of 1929: Are We on the Verge of a Repeat?

http://www.alternet.org/story/56443/

Hedge funds have helped create a counterfeit economy that some experts say could lead to another full-blown economic depression.

[A senior adviser to President Bush] said that guys like me were ''in what we call the reality-based community,'' which he defined as people who ''believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality.'' I nodded and murmured something about enlightenment principles and empiricism. He cut me off. ''That's not the way the world really works anymore,'' he continued. ''We're an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you're studying that reality -- judiciously, as you will -- we'll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that's how things will sort out. We're history's actors ... and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.'' -- Ron Suskind, "Without a Doubt," New York Times

The hypermarket beckons

News flash: The American economy is a hyperreality engineered by Ph.D.s working hand-in-hand with colluding media multinationals, political officials and some of the biggest names in business -- and the banks that invest in them. In other news, greed is still good.

Of course, the idea that Wall Street is corrupt is as old as Wall Street itself. After all, the immortal "Greed is good" aphorism was muttered by a white-collar criminal in the 1987 movie named after Wall Street, which was directed by a guy, Oliver Stone, who made his name in postmodern cinema and political agitation. In fact, a film of the same name came out in 1929, the year of the stock market crash. And so the narrative replicates.

Speaking of replicants, Oliver Stone is a man who tackled not only labyrinthine presidential conspiracies in the 1991 film JFK but also the numb pathos of 9/11 in last year's World Trade Center. Indeed, Wall Street indirectly tackled the junk bond and insider trading economic screw-jobs that riddled the '80s like so many overpriced, overly puffy hairdos. Stone envisioned the film as Crime and Punishment on Wall Street, which was only partially fitting for the time because there was a ton of crime and very little punishment.

And the more things have changed, the more they have stayed the same. Indeed, only the nomenclature has been altered. Instead of junk bonds and insider trading, we have hedge funds and private equity takeovers. And instead of Gordon Gekko and Wall Street, we have Fox News mogul Rupert Murdoch and, soon, the Wall Street Journal.

In the 1980s, guys like Michael Milken and Ivan Boesky -- who anticipated the "Greed is good" phrase with a 1986 commencement speech at Berkeley in which he stated, "Greed is all right. ... I think greed is healthy" -- were riding high on schemes that failed. Both served as inspirations for Stone's Wall Street scumbag Gordon Gekko, but both got off with a few years in prison and a few hundred million dollars lost. Milken shaved a 10-year sentence down to two, and in 2007, still had a net worth of about $2 billion. Roll the happy ending.

But the hyperreality does not end there, and by hyperreality I mean simply a reality that exists outside the one you live in, whoever you are. It can come in many forms. Film is one such simulation, network and cable news is another, and our two-party political machine, as Ron Suskind explains in the quote at the top of this article, is a finer-tuned one still. But they all collide and collude in the social space of Wall Street and its various markets, on the internet and on the trading floors of the New York Stock Exchange and onward.

Take Milken's favored high-yield junk bonds, for example, which are basically bonds that are rated below investment grade by ratings organizations like Standard and Poor's or Moody's and therefore subject to not only a much higher risk of default or other cash-sucking crashes but also higher paydays if you can make them work. To do that, you need a little help from your friends and unsuspecting investors, which is why Boesky and Milken went to jail for suckering friends and strangers into dense schemes that went nowhere.

And if that whole scam sounds familiar, that is because, as is always the case with hyperreality, it is happening again. Yet this time, it is happening in an information age in which 97 percent of stock transactions are conducted electronically. And this time it is not because of junk bonds, but because of hedge funds, mortgage-backed securities, subprime loans and a bizarro virtual scheme known as naked shorting, which has been around as long as -- and played a role in -- the 1929 crash, and according to some, could trigger the next one any day now.

"We've divorced the system from paper," explained Overstock.com CEO and hedge fund activist Patrick Byrne to me by phone, "and since then it's become easier to divorce it from reality. But the problem is that so much has been drained out of the system using these tools that the money is not there. If this gets exposed, the money is not there. It's been turned into Ferraris and mansions in the Hamptons. It can't be paid back. The system is going to vapor lock."

Nailing subprime's number

The recent implosion of the subprime housing market -- in which people with little or no significant savings of their own are offered huge loans for little or no money down for houses often but not always located in fast-track developments -- shares similarities with the junk bond burnout of the 1980s.

Indeed, the subprime loans that carved America's cash cow for the last few years were rated just as poorly as Milken's junk bonds and ended up pretty much the same way: with the scattering of investors and players from a hailstorm of collapsed debts, besmirched reputations and impending government oversight. While Milken's house of cards was built on leveraged buyouts (LBOs), where an acquirer issued a bond to pay for an acquisition that he would pay back with funds yet to be earned, the engine that made subprime's train roll off the tracks are collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), which are intricately structured and packaged strategies pooled together to decrease the risk generated by the fact that they are usually home equity, car and credit loans so poorly rated that they promise only collapse for those who get them and seized assets for those who offer them.

Like I said, same scam, different name.

But this time the outlook is worse. For one, the subprime housing implosion has been a disaster for the market as a whole. Consider the case of Bear Stearns: Their hilarious hedge holes -- the CDO-heavy High-Grade Structured Credit Strategies Enhanced Leverage Fund and its sister, High-Grade Structured Credit Fund -- cratered in early June, going from about $10 billion to a few hundred million in assets within a matter of months, even though the hedge fund itself had been barely up and running for more than 10 months.

But here's the thing about hedge funds that makes them so lucrative: You can play both sides against the middle -- the middle class, come to think of it -- and still win. Huge. So it was no surprise when the Wall Street investment titan decided to bail out its own hedge fund, to which it had committed only around $35 million, with over $3 billion and counting. As Bear Stearns Chief Financial Officer Sam Molinaro explained in a conference call, "There continues to be significant value in it."

For those who work there, maybe. Meanwhile, those who invested in Bear Stearns' hedge funds are out of money, and those crushed beneath their so-called high-grade structures are out of their homes and cars, which are in turn seized and put back into the asset pool. Not a bad business if you can get it.

And while Molinaro's estimation of Bear Stearns hedge fund may sound rosy, the hemorrhaging of the housing market is anything but. Open up any newspaper to the business section and look for any headlines involving plummeting home sales or declining property values, and you'll taste the bitter pills, because Bear Stearns is by no means alone. Swiss wealth management powerhouse UBS shuttered its Dillon Read Capital Management hedge fund after losing over $120 million invested in the subprime Kool-Aid. Then there was Amaranth Advisors, which pulled off the biggest hedge fund collapse in history when it blew almost $6 billion of its $9 billion in assets in a mere week after a highly leveraged bet, although it threw its chips down on the price of natural gas

That's not the housing market, you say? Good point. In fact, the point altogether. As we shall see, hedge funds spread their bets across the entire economic table, and they are armed with that most virtual of investment strategies. It is called the naked short.

Getting naked with shorts

For those who don't know how hedge funds work, consider the casino table favorite known as craps. And for those who make their living or leisure playing it, forgive this short introduction.

Craps is a game that's been with us, to get hyperreal about it, since the Crusades, which itself was a series of highly risky but also highly lucrative takeovers. It is played on a table littered with numbers and any number of betting strategies, but rolls are governed by what is called the point, which is decided by the first roll of the session known as the come-out and is usually 4, 5, 6, 8, 9 or 10. These are the numbers the dice have the greatest chance of repeating on subsequent rolls, although the one they can hit the most is 7, given all the possible combinations. For this reason, if you roll a 7 when the point is any of the aforementioned numbers, the session is ended and the casino takes all the money off the table, pockets it and then hands the dice off to the next roller. Sucker.

If you want to join a craps game, you have to put your money down on the Pass Line, which is governed by the point. If the point is 8, and the roller hits it again, everyone wins and all the bets on the table are paid out. In other words, when you play craps, you are usually betting that you will hit another number besides 7 and make a ton of dough before you eventually do in fact hit it. That is called Pass Line play.

But there is another way to play craps, and that is to play the Don't Pass Line, which is basically a bet on 7. So there you are, throwing down your money and hoping that everyone at the table rolls a 7 while they're hoping to roll anything but. If they lose, you win. Not very popular, but since you're betting with the house, and the house always win, not a bad betting strategy.

But there's an even better one and that's playing both lines at the same time, which was frowned upon the last time I did it in Vegas, but was nevertheless legal. By playing the Pass and Don't Pass Line off of each other, you let your place bets make all your money for you, and let the line bets offset each other. If you live long enough in the game, you can make buckets of cash in advance of the end that always comes.

Hedge funds are pretty much the same thing. They play both sides of the market, going long on stocks they feel will pay off in the end, and going short on those they don't. Except for one glaring difference, according to Overstock.com CEO and hedge fund activist Patrick Byrne.

"Craps is a good analogy," he told me via email. Except that hedge funders "are also the croupier and own the casino management and the gaming regulators."

Byrne isn't the only activist convinced of the analogy. Engineer, investor advocate and InvestigatetheSEC.com webmaster David Patch took it much further in an email exchange. "Hedge funds are more and more becoming a craps game," he assented via email, "but the problem is more than just those sitting at the tables become the losers. The industry pools their bets in such concentrated levels that the funds begin to drive the markets to levels beyond the values that would normally be dictated by the fundamentals."

But according to Robert J. Shapiro, Clinton undersecretary of commerce for economic affairs and senior fellow at the Democratic Leadership Council's Progressive Policy Institute, it's not the hedge funds or more particularly their both-sides-against-the-middle strategies that are the problem per se. "The ability to hedge investments encourages investment," he told me by phone. "You get more of it because you can hedge it. It reduces the likelihood that financial institutions are going to find themselves in trouble if the markets go against them, if they guess wrong."

What brings Shapiro, Byrne, Patch and a growing legion of investors, scholars and politicians together is the hyperreal practice known as naked shorting. Recall craps and the Don't Pass Line: In it, you are betting on failure, or as the stock market would term it, devaluation. Well, Wall Street has a Don't Pass Line of its own, and it's called shorting. Just as the Don't Pass player is waiting for a 7 roll and the house to clean you out, short investors are literally banking on the collapse of some stocks. As Shapiro explained it, it's a perfectly legal -- if not, as in craps, uncool -- way of preying on those companies living on borrowed time.

"Short sells are fine because just as you buy a share on the belief that the stock is going up, you short a company on the belief that the price is going down," Shapiro said. "In both cases, you inject information into the market. Short sales are a way of injecting negative information into the market. There's nothing wrong with them; they've been around for a long, long time."

Forget for a moment that we are talking about injecting information, rather than actual money, into the market. Information, as anyone born in the era of the personal computer or Internet understands all too well, is easily manipulated. But if Shapiro's first proposition rings a bit hollow, at least the second one is true. In fact, as Shapiro clarified, it was massive if unregulated short sales, known as naked shorts, that gave the infamous 1929 crash (which in turn spawned the Great Depression, its long, long legs).

"There were a lot of unregulated short sales in the stock market crash; that's true," Shapiro confirmed. "And regulating short sales were part of the initial regulation from the SEC in 1936."

Byrne is a bit more colorful on the subject. "I do think it played a role. Hedge funds were called pools back then. Rich guys got together, pooled their capital and manipulated the stock market. And, in fact, newspapers covered the pools like they would cover sports teams; it was public entertainment. It wasn't too dissimilar from the way the New York Times is trying to make rock stars out of hedge funders today."

In other words, naked shorts are a final confirmation that hyperreality has been with us as long as the Bible. They are virtual transactions, ones that never actually occur.

"In short sales," Shapiro explained, "you don't own the share you sell; instead you borrow it. Then you replace it when you cover the short. If you're right and the price has gone down, you replace it at a lower price, and the difference between what you sold it for and what price you replaced it at is your profit. The problem with a naked short is that you don't borrow the share you sell. You sell it without ever borrowing it. In effect, you invent a share."

If this is beginning to sound like a game of Monopoly built on fake money, that's because it is. By injecting so many invented shares into the market using naked shorting, hedge funds have not only created an economy in which they can manipulate the stocks of companies smaller than Microsoft and Wal-Mart, but they have also created a market in which there are more shares than actual stocks. And that's about as hyperreal as an economy can get.

"It's essentially counterfeiting," Byrne added. "You're creating counterfeit shares in the system. It works like this. In a normal stock transaction, you give me money and I give you stock. And not paper stock anymore. It turns out that there is a loophole in the system: When I come to give you the stock that you bought, if I don't actually have any stock, I can give what is effectively an IOU. Now you never know about this unless you know the right question to ask your broker, but it's possible that all you really have in your account is an IOU from your brokerage account from a different broker working with a hedge fund."

It is precisely this imbalance between real and invented shares that Byrne and others argue is primed to explode the subprime collapse into a full-blown economic depression.

"There are a lot of us who think we are living on the edge of 1929," Byrne continued. "When you consider what's happened with mortgage-backed securities, you get the feeling these might be the first rumblings. There may be more IOUs in the system than there is liquidity, in which case the entire thing is going to vapor lock as soon as it is exposed. One of the healthiest indications of the vibrancy of an economy is capital formation. Seven years ago, America was responsible for 57 percent of IPO capital raised around the world. Now it's down to 16 percent. A national disaster."

Greed is God

So what is the remedy for this historical collusion among money, markets and the managed realities of naked shorting and hedge fund buyouts? A political solution may be on the way, according to Shapiro.

"The SEC has just very recently finally agreed that this is a very serious problem that is destroying some companies and undermining the integrity of the markets," he explained. "They came out with regulations in 2005, which we criticized for having huge loopholes. But this year, the SEC finally said their attempts to address the problem have failed, so they are seriously tightening the regulations. Now we'll see if they enforce them."

But history, as always, likely will teach a different lesson. Consider two events in that regard. The first happened after -- and because of -- the 1929 Crash: The Glass Steagall Act of 1933 mandated the separation of bank types according to their business, after the Senate-led Pecora Commission investigation of the crash found that collusion between commercial and investment banks played a major role in it. That act stood for 66 years, until none other than Bill Clinton repealed it in 1999, and here we are again.

Here's the other lesson: According to a recent Financial Times story, "Barack Obama received more donations from employees of investment banks and hedge funds than from any other sector, with Lehman Brothers, Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan Chase among his biggest sources of support." While Obama has already promised to increase regulation on hedge funds and the tax burden on private equity groups (or today's "pools," as Byrne explained them), if he becomes president, one can imagine he'll be singing quite a different tune if he becomes the first black man in history to run the White House.

Throw in the fact that Rupert Murdoch is set to take over the Wall Street Journal, the paper of record for these subjects and scams, and you have more of the same reality programming.

Murdoch's holdings would probably give the Pecora Commission fits: Not only does he own Fox News and now the Wall Street Journal, to go along with the New York Post, MySpace, DirecTV, HarperCollins, the Sunday Times, TV Guide, the Weekly Standard, 20th Century Fox ... Stop me if you've had enough, but he's also slated to unveil Fox Business Network on Oct. 15, which no doubt will team up with all of his other assets to turn Murdoch into something else besides a propaganda arm of the Bush administration or, in fact, the puppeteer who pulls its strings.

And for those of you who think that may be too broad a generalization, consider this: As the Huffington Post explained, "By taking advantage of a provision in the law that allows expanding companies like Mr. Murdoch's to defer taxes to future years, the News Corp. paid no federal taxes in two of the last four years, and in the other two, it paid only a fraction of what it otherwise would have owed. During that time, Securities and Exchange Commission records show that the News Corp.'s domestic pretax profits topped $9.4 billion."

Can you say free ride?

For those who argue that Murdoch and hedge funds are miles apart, consider this: He knows how to hedge just fine, thanks. After all, it was none other than current Republican presidential candidate Rudolph Guiliani who in 1996 threatened to run Fox News commercial-free on a city-run access channel if Time Warner Cable didn't end its 11-month battle to keep Murdoch out of New York households. It's also important to note, especially if you are Murdoch, that it was Guiliani who implemented RICO statutes to nail Michael Milken with 98 counts of racketeering and fraud. But Murdoch is an old hand at hedging: He's so far funneled $40,000 into Hillary Clinton's campaign. Whoever loses, he wins.

Like I said, nice business if you can get it.

Black Monday is the name given to Monday, October 19, 1987, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) fell dramatically, and on which similar enormous drops occurred across the world. By the end of October, stock markets in Hong Kong had fallen 45.8%, Australia 41.8%, the United Kingdom 26.4%, the United States 22.68%, and Canada 22.5%. (The terms Black Monday and Black Tuesday are also applied to October 28 and 29, 1929, which occurred after Black Thursday on October 24, which started the Stock Market Crash of 1929.)

The Black Monday decline was the second largest one-day percentage decline in stock market history. The largest one occurred on Saturday, December 12, 1914, when the DJIA fell 24.39%. However, in that case, the New York market had been closed since July due to the outbreak of the First World War. The greatest point loss in DJIA history was on Monday, September 17, 2001, 684.81 points, six days after the September 11, 2001 attacks and the first day after which the market was open.

A certain degree of mystery is associated with the 1987 crash. Many have noted that no major news or events occurred prior to the Monday of the crash, the decline seeming to have come from nowhere. Important assumptions concerning human rationality, the efficient market hypothesis, and economic equilibrium were brought into question by the event. Debate as to the cause of the crash still continues many years after the event, with no firm conclusions reached.

In the wake of the crash, markets around the world were put on restricted trading primarily because sorting out the orders that had come in was beyond the computer technology of the time. This also gave the Federal Reserve and other central banks time to pump liquidity into the system to prevent a further downdraft. While pessimism reigned, the market bottomed on October 20, leading some to label Black Monday a "selling climax", where the excess value was squeezed out of the system.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Monday_(1987)

The stock market crash of 1987 was the largest one day stock market crash in history. The Dow lost 22.6% of its value or $500 billion dollars on October 19 th 1987! In order to understand the crash, we must first study the cause.

http://www.stock-market-crash.net/1987.htm

1986 and 1987 were banner years for the stock market. These years were an extension of an extremely powerful bull market that started in the summer of 1982. This bull market had been fueled by hostile takeovers, leveraged buyouts and merger mania. Companies were scrambling to raise capital to buy each other out, in essence. The philosophy of the time was that companies would grow exponentially simply by constantly purchasing other companies. In leveraged buyouts, a company would raise massive amounts of capital by selling junk bonds to the public. Junk bonds are simply bonds that have a high risk of loss, so they pay a high interest rate. The money raised by selling junk bonds, would go towards the purchase of the desired company. IPOs were also becoming a commonplace driver of the markets. An IPO is when a company issues stock for the first time. “Microcomputers” were also a top growth industry. People started to view the personal computer as a revolutionary tool that will change our way of life, and create wonderful profit opportunities. The investing public was caught up in a contagious euphoria, similar to that of any other bubble and market crash in history. This euphoria made people, once again, believe that the market would always go up.

Despite the strong economic growth, SEC was unable to prevent shady IPOs and conglomerates from proliferating. In early 1987, the SEC conducted numerous investigations of illegal insider trading. This created a wary stance from many investors at this point. Also, due to the extremely strong economic growth, inflation was now becoming a concern. The Fed rapidly raised short term interest rates to temper inflation. This, unfortunately, had an effect of hurting stocks as well. Many institutional trading firms started utilizing portfolio insurance to protect against further stock dips. Portfolio insurance is a practice that uses futures contracts as an insurance policy. People that hold the futures contracts can make money as the market crashes, offsetting the losses in the stock holdings. After interest rates had risen, many of the large institutional firms started using portfolio insurance all at the same time. The futures market was taking in billions of dollars within minutes, causing the futures market and the stock market to crash from instability. Additionally, common stock holders all wanted to sell simultaneously. The market couldn’t handle so many orders at once and most people couldn’t sell because there weren’t ANY buyers left!

Within one day, 500 billion dollars was evaporated from the Dow Jones index. Markets in every country around the world collapsed in the same fashion. When individual investors heard that a massive stock market crash was in effect, they scrambled to call their brokers. This was unsuccessful because each broker had many clients. Many people lost millions instantly. Some unstable individuals, who had lost fortunes, went to their broker’s office and started shooting. Several brokers were killed, despite the fact that they had no control over the market action. The majority of investors who were selling, didn’t even know why they were selling, except that they “saw everyone else selling”. This irrational mentality caused the extreme market crash. Most futures and stock exchanges were shut down for the day.

Around this time, the Fed started to intervene. Short term interest rates were instantly lowered to prevent a depression and a banking crisis. Remarkably, the markets recovered quickly from the worst one day stock market crash. Unlike the stock market crash of 1929, the market quickly started on a bull run, once again. This was powered by companies buying back their stocks that were undervalued after the severe crash. Additionally, the Japanese Nikkei index was embarking on its own massive bull market. This tremendous momentum helped pull the US stock markets to new heights never seen before. Some benefits came as a result of the 1987 stock market crash. For example, the circuit breakers system was implemented, which electronically stops stocks from trading if they plummet too quickly. This will prevent any future one day vertical drops, like 1987.

Once again, the remarkable similarity between all of the market crashes is striking. It seems that after all of the historical market crashes, people would learn to foresee a coming financial disaster. This rarely happens, of course, which is why there is constant opportunity for the smart money to prosper from the irrationality of other people.

A dire prediction: Market drop to be 'short, sharp and nasty'

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/story/LAC.20070810.RBEAR10/TPStory/Business

Even before the latest market gyrations, strategist Nick Majendie thought there was a 75- to 80-per-cent chance that North American stock markets could drop 10 to 20 per cent. Now, he has raised the odds of that happening and suggested that the decline could possibly be worse than previously expected, which is probably not what many investors wanted to hear on a day when the markets again experienced that sinking feeling.

Not that he is the only market watcher suggesting that the selloff still has a way to go. Mary Ann Bartels, technical research analyst at Merrill Lynch & Co. Inc., said in a report earlier this week that the U.S. market could potentially drop 15 per cent, a correction that would be in line with previous slides from market peaks.

Mr. Majendie, who is the senior vice-president of Canaccord Capital Corp., said in a report yesterday that "we see the most likely outcome for the U.S. stock market as similar to 1987 and 1998; a 'short, sharp and nasty' decline of 20 per cent and a Fed [U.S. Federal Reserve Board] response with a cut in interest rates." He also expects a similar decline for the Canadian market.

In 1987, the Standard & Poor's 500-stock index tumbled 20.5 per cent on what became known as Black Monday - Oct. 19. But actually the stunning loss that day continued a decline that started on Oct. 5. Measured against the close of that day, the drop was actually 31.5 per cent.

The S&P/TSX composite index followed more or less the same path, but the selloff was more muted on this side of the border, with the total decline beginning on Oct. 15 and ending on Oct. 20 coming in at 19 per cent. The loss from Oct. 5 at 24.1 per cent was also less than that of the S&P 500.

In 1998, investors had to contend with what went into the history books as the Asian contagion. That problem was felt most deeply in August, 1998. Over the course of that month, the S&P 500 fell 14.6 per cent from the beginning of the month to the end. Extend the time period a little and the size of the loss increases. The TSX composite dropped 20.2 per cent over the month.

Mr. Majendie has become more pessimistic as the markets have gyrated. "The principal reason for the higher odds is that the recent declines in equity markets have been global," he explained. "The credit balloon was a global phenomenon," he said. Moreover, price/earnings multiples of "many indices around the world were near record highs, largely due to the activity of private equity and leveraged buyout players using high levels of debt to bid up premiums on target companies," he added. But credit has since tightened, which means liquidity is drying up. Investors typically react to such a situation by selling initially to take profits but later as the decline accelerates, to preserve capital, he said.

But Mr. Majendie is not suggesting the markets will go straight down from here. Indeed, he fully expects bear market rallies over the next while, "since the strategy of 'buying the dips' has been so successful over the last five years." He feels such rallies should be used as opportunities to sell, rather than buy.

Ms. Bartels said in her report that the U.S. market is "clearly oversold" but it is a "bad oversold" with numerous technical indicators indicating the correction still has further to go. For example, she noted that according to an Investors Intelligence poll released last week, 26 per cent of financial advisers surveyed were bearish on the market. "Readings need to rise to the 35 per cent to become oversold and positive for the U.S. equity markets," she said. (The bearish sentiment rose in this week's poll to 31.5 per cent, which is still short of the oversold level.)

So is there any good news in all that? Yes, there actually is some. Ms. Bartels still likes the long-term outlook of the U.S. market. She doesn't expect that the correction will break the major trend in the market, which is up, and suggests that the current weakness will ultimately prove to be a correction, but not a reversal, of the secular bull market trend.

And what did the indexes do in 1987 and 1998? In 1987, the S&P 500 basically ended the year where it began, while in 1998, it advanced a hefty 26 per cent over the course of the year even with the August selloff.

Dow sinks 387 on renewed credit concerns

http://www.boston.com/business/markets/articles/2007/08/09/wall_street_rises_on_tech_strength/?p1=MEWell_Pos4

NEW YORK --Wall Street's deepening fears about a spreading credit crunch sent stocks plunging again Thursday, with the Dow Jones industrials extending their series of triple-digit swings and falling more than 380 points. The catalyst for the market's latest skid: a French bank's announcement that it was freezing three funds that invested in U.S. subprime mortgages.

The announcement by BNP Paribas raised the specter of a widening impact of U.S. credit market problems. The idea that anyone -- institutions, investors, companies, individuals -- can't get money when they need it unnerved a stock market that has suffered through weeks of volatility triggered by concerns about tight credit and bad subprime mortgages.

A move by the European Central Bank to provide more cash to money markets intensified Wall Street's angst. Although the bank's loan of more than $130 billion in overnight funds to banks at a low rate of 4 percent was intended to calm investors, Wall Street saw it as confirmation of the credit markets' problems. It was the ECB's biggest injection ever.

The Federal Reserve added a larger-than-normal $24 billion in temporary reserves to the U.S. banking system.

The concerns that arose in Europe and spilled onto Wall Street underscored the potential worldwide ramifications of an implosion of some subprime loans and perhaps also weakened arguments that strength in the global economy could help keep profit growth going in the U.S. among large companies that do business overseas.

The ECB's injection of money into the system is an unprecedented move, said Joseph V. Battipaglia, chief investment officer at Ryan Beck & Co., adding that it shows that problems in subprime lending are, in fact, spreading into the general economy.

"This is a mini-panic," he said. "All the things that had been denied up until this point are unraveling. On top of this, retail sales were mediocre, which shows that indeed, the housing collapse is affecting the consumer."

Retailers released July sales figures Thursday that were overall disappointing.

The Fed didn't soften its stance on inflation after leaving short-term interest rates unchanged Tuesday. However, the renewed credit market concerns spurred bond traders who bet on its next move to predict that the Fed will cut rates at its meeting next month. Before Thursday, traders had bet on a 1 in 4 chance of such a cut.

The Dow fell 387.18, or 2.83 percent, to 13,270.68.

Thursday's pullback continued an erratic pattern of triple-digit moves in the Dow since the index closed at a record 14,000.41 on July 19. Eleven of the 15 ensuing sessions have ended in a triple-digit gain or loss. Gains have been evaporating at the first mention of trouble in housing, subprime lending or the credit markets.

With Thursday's decline, the Dow is about 730 points, or 5.2 percent, below its record close. Some experts have been calling for a textbook correction -- a pullback of at least 10 percent. At its lowest close since the market's high, Friday's finish of 13,181.91, the Dow was 5.85 percent below the record.

Bonds rose sharply Thursday as investors again sought the relative safety of Treasurys, pushing down the yield on the benchmark 10-year note to 4.79 percent from 4.89 percent late Wednesday.

The broader Standard & Poor's 500 index fell 44.40, or 2.96 percent, to 1,453.09.

Before Thursday, the S&P had its best three-day winning streak in nearly five years. But the latest pullback was the biggest point drop and percentage loss for both the Dow and the S&P since a market decline on Feb. 27., that owed in part to concerns about subprime loans.

The Nasdaq composite index fell 56.49, or 2.16 percent, to 2,556.49. On Wednesday, it posted its biggest point gain in more than year. And while Thursday's loss was sharp, last Friday's was more severe.

Despite Thursday's slide, the major market indexes are still up for the week, given that stocks rose sharply the first three sessions of the week.

The pullback came after a BNP Paribas unit said it was suspending three funds together worth about $3.79 billion and wouldn't make investor redemptions until it could determine net asset values.

The funds invest in part in subprime mortgages through a process known as securitization. Investment banks bundle together mortgages -- including those from subprime borrowers -- and sell them off to investors such as hedge funds, mutual funds and other institutional investors. Buyers of such securities are seeking the steady flow of income from homeowners making their mortgage payments.

"It just kind of brought the fear back," said Douglas Peta, market strategist at J.& W. Seligman in New York.

"In the last couple of days I think people maybe thought that an all-clear had been sounded," he said referring to some of the subprime loan concerns.

"This just highlights that there is not going to be an immediate resolution," he said of the companies that are trying to determine their exposure to bad subprime loans.

Shares of financial companies, which investors have fled recently amid lending concerns, took another beating Thursday. Citigroup Inc. fell 5 percent, as did fellow Dow component JPMorgan Chase & Co.

In another sign of credit market trouble, Home Depot Inc. warned that the sale of its wholesale business might bring in less than expected. The world's largest home improvement retailer, which also cut how much it intends to pay to repurchase stock, said volatility in the stock, debt and housing markets has led to the possible repricing. Home Depot fell $2.01, or 5.3 percent, to $35.79, and was the worst performer of the 30 Dow components.

But American International Group Inc., one of the world's largest insurers, on Thursday reassured investors that it remains comfortable with its exposure to the subprime lending market as an investor, lender and mortgage insurer. AIG, which reported a 34 percent jump in second-quarter profit late Wednesday, said it has enough cash and liquidity and "does not need to liquidate any investment securities in a chaotic market."

AIG fell $2.18, or 3.3 percent, to $64.30, however.

The dollar was mixed against other major currencies, while gold prices fell. Light, sweet crude fell 56 cents to $71.59 per barrel on the New York Mercantile Exchange.

Declining issues outnumbered advancers by about 4 to 1 on the New York Stock Exchange, where consolidated volume came to a heavy 5.76 billion shares compared with 5.3 billion shares traded Wednesday.

The Russell 2000 index of smaller companies fell 10.79, or 1.36 percent, to 784.87.

The Chicago Board Options Exchange's volatility index, often called the "fear index," rose Thursday to its highest level since April 2003.

European stocks plunged. Britain's FTSE 100 lost 1.92 percent, Germany's DAX index fell 2.00 percent, and France's CAC-40 fell 2.17 percent after being down more than 3 percent. Japan's Nikkei stock average rose 0.83 percent. Hong Kong's Hang Seng index fell 0.43 percent.

Q&A: World stock market falls

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/6939899.stm

Stock markets around the world have been falling sharply on fears of a credit crunch that could affect the financial sector. What is causing the fall, and how will it affect the ordinary individual?

What has been happening to the world's stock markets?

The value of the world's major companies has taken a tumble as the world's stock markets have plunged in the past two days - one of several such sharp declines in the past few months.

The move has wiped billions of dollars off the value of shares owned by individuals and institutions such as pension funds and insurance companies.

This most recent fall started when a French bank, BNP, said it would freeze three investment funds because it could no longer accurately measure their value.

Fears that more undisclosed bad debts would surface led other banks to cut back on their everyday lending to one another.

That led the European Central Bank to step in and boost the amount of money in the financial system.

Markets fell around the world because they were nervous that the problems are not just confined to French banks, but are more widespread in the financial sector.

What are the markets worried about?

The underlying fear relates to the so-called sub-prime mortgage market in the US.

In the past five years, extraordinarily low interest rates in the US have led banks and other financial institutions to lend substantial sums of money to people with poor or no credit histories.

The idea was that, even if they eventually couldn't pay, the banks could recoup any losses by repossessing and reselling the houses - and in any case, house price rises would cushion the blow.

In the most extreme cases, mortgage brokers were handing out what came to be known as "Ninja" loans, to people with no income, no job and no assets.

Often the loans were "no-doc", where the borrower did not have to provide proof of how much they earned. Recent research suggests that in many if not most of these, borrowers (or their brokers) lied about their income.

But now as interest rates have risen, so have repossessions. The US housing market has collapsed, and the banks find themselves saddled with a lot of bad debts.

However, it is not just a problem for US banks.

Globalisation has meant that much of this mortgage debt has been sliced up into small pieces, repackaged as "collaterised mortgage obligations" and sold on to financial institutions and individual investors around the world.

And now, no one, including the central banks, is certain how much of these bad debt financial institutions or individuals are holding.

What is a credit crunch?

There are fears that the worries about bad debts could turn into a financial panic.

Because no one knows which banks are sound, investors may rush to withdraw their money from a large number of institutions, which would otherwise be solvent.

This so-called liquidity crisis could destabilise the economy: forcing interest rates up sharply, causing some banks to collapse, and preventing lending to legitimate companies who want to invest.

It is this fear that the world central banks are trying to address by injecting cash into the system - making it clear that they will not allow major banks to fail just because of a rush on their funds.

They took similar action after September 11, 2001, to prevent the terrorist attacks in the US from spreading financial panic around the world.

What are the wider implications?

Even if the central banks stem the financial panic, there seems to have been a general shift in market perceptions about risk.

Generally, the risky the investment, the higher the interest rate - but now the additional premium for risky investments (the "spread") is set to widen sharply.

When people with money to lend become worried about risks, they tend to put their money in safe investments.

So there has been a rush to invest in government bonds, like US Treasury bonds, and safe currencies, like the yen.

In contrast, people are now demanding much higher interest rates to lend to smaller companies or to the governments of developing countries.

And there is almost no market at the moment for the debt relating to sub-prime mortgages or leveraged buy-outs - corporate takeovers funded by taking on big debt rather than with cash or shares.

This may mean that this is much less takeover activity than in the past few years, when it has been mainly funded by private equity funds borrowing money cheaply.

That could also lower the value of the stock market in the short-term.

How long will it go on?

Stock market fluctuations are a normal part of stock market activity, and no one can say how far shares could fall or how long the slowdown could persist.

Markets have had quite a sharp rise in the past 18 months, and the current correction may simply return them to previous levels.

Broadly, company profits have been strong, and the world economy seems to be entering a period of revival, especially in Europe and Japan.

However, stock markets look at future expectations, so they may be concerned that corporate profits have already peaked.

And even if stock markets recover, it looks like the re-pricing of risk - making it more expensive to borrow for certain kinds of investments - is here to stay.

The world's major central banks, with the exception so far of the US Federal Reserve, look set to continue to raise interest rates to combat inflationary fears - even if they pause to wait until markets calm down.

What does it mean to you?

Many individuals own stocks and shares - about half of all US households, and around a quarter of those in the UK.

If the stock market falls continue, they may feel less wealthy - and be less likely to buy goods and services, slowing the economy.

In addition, many pension funds own shares which make up part of their portfolio used to pay people's occupational pensions.

If shares fall, they may have less money to pay future pensions, and employee contributions may have to rise.

Already in both the UK and US many companies have closed company pension schemes to new employees.

Finally, the impact on businesses could be mixed.

Smaller, more risky ventures could find it more difficult to get funding, slowing the pace of innovation.

But big companies might become less vulnerable to takeovers, which could mean fewer job losses and restructuring costs as long as profits keep up.

A Scary Friday on Wall Street

Credit-crunch fears escalated on Friday as stocks looked to fall further. The Fed stepped in, saying it would provide liquidity "as necessary"

http://www.businessweek.com/investor/content/aug2007/pi20070810_666529.htm?chan=top+news_top+news+index_top+story

What would normally be a quiet summer Friday was being hijacked by fear and anxiety as Wall Street readied for another wild day.

Fear about the world's credit markets was setting market indexes up for steep declines at the opening Friday morning. However, stock index futures cut their losses and bonds added to their gains Friday morning after a statement from the Federal Reserve stating that it would provide liquidity to the financial markets.

The expected drop on Friday on top of a sharp drop on Thursday, when anxieties about the spreading subprime crisis sent the Dow Jones industrial average down 387.18 points, or 2.84%, to 13,464.06, one of the biggest one-day point losses for the Dow ever.

The broader S&P 500 dropped 44.40 points, or 2.97%, to 1,453.09. The tech-heavy Nasdaq composite index tumbled 56.49 points, or 2.16%, to 2,556.49.

However, stock index futures cut their losses and bonds added to their gains Friday morning after the Fed issued a statement that said it "will provide reserves as necessary through open market operations to promote trading in the federal funds market at rates close to the Federal Open Market Committee's target rate of 5-1/4%." The central bank noted that "in current circumstances, depository institutions may experience unusual funding needs because of dislocations in money and credit markets."

Overnight the Fed, joining banks in Europe, Japan and Australia,added liquidity to the banking system to try to alleviate any credit crunch.

But stocks plunged in Europe and Asia. In London, the FTSE 100 index was off 2.93% to 6,087.2. Germany's DAX index fell 1.5% to 7,342.06. In Paris, the CAC 40 index was dropped 2.22% to 5,500.15.

In Japan, the Nikkei index finished an ugly session lower by 2.37%, at 16,764.09. In Hong Kong, the Hang Seng index plunged 2.88% to 21,792.71.

For weeks, markets have been worried by the spreading of a credit crisis from subprime mortgage loans to other forms of risky debt. News on Thursday suggested the credit crisis was going from bad to worse by crossing the Atlantic.

Markets skidded on reports that a unit of BNP Paribas said it would freeze three funds invested in U.S. asset-backed securities. It cited "the complete evaporation of liquidity" in certain parts of the U.S. securitization markets, which make it "impossible to value certain assets fairly regardless of their quality of credit rating."

One sign of investor anxiety: The CBOE volatility index, or VIX, widely regarded as a fear gauge for the stock market, surged to 25.93 Thursday, after reaching a 52-week high of 26.88 earlier in the session.

Technical signs for the market could cause further anxiety. The S&P 500 has entered a "black hole" where there is little support or resistance, according to S&P chief technical strategist Mark Arbeter. The reason there is a void of support and resistance in this zone is because the index moved through this range very quickly in April without pausing, notes Arbeter, "so there is very little in the way to slow the market down."

Bill Larkin, portfolio manager of fixed income at Cabot Money Management says now is a good time for investors to determine exactly how risky their investments are.

Credit markets around the world, not just in the U.S., are raising the price of risk. "This is a global event," he says. "Nobody knows where this is going" because debt markets work slowly - "like watching paint dry," Larkin says. "Everybody's waiting for the other shoe to drop."

In economic news Friday, U.S. import prices surged 1.5% in July after a 0.9% increase in June. Import prices are up 2.8% on a year over year basis. Oil prices, up 7%, made up most of the increase. "The data are further bad news on inflation," says Action Economics, "but will generally be ignored in the face of current market turmoil."

Oil prices have been falling amid speculation that lower economic growth would hurt demand. September West Texas Intermediate crude oil futures fell another 92 cents to $70.67 per barrel Friday.

Among stocks in the news on Friday, Countrywide Financial (CFC) says it's facing "unprecedented disruptions" in debt and mortgage markets that could hurt earnings and the firm's financial condition.

Deutsche Bank (DB) reportedly has lost money in funds invested in asset-backed securities. A fund that totaled 2.1 billion euros now were worth 3 billion at the end of July, Reuters reports, though the fund remains open.

Washington Mutual (WM) says, in an SEC filing, that market conditions have "adversely affected" its ability raise liquidity by selling off home loans.

Treasury Market

Bond prices were rising amid the tumult in equities. The 10-year Treasury was up 07/32 to 100-02/32 for a yield of 4.74%.

Bulls and Bears

Lindsay Hall - Lindsay's Hot Pick

![Brotherhood" (2006) [TV-Series]](http://photos1.blogger.com/x/blogger2/1421/379621144723082/211/z/425926/gse_multipart33129.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment