Newark is the largest city in New Jersey, United States, and the county seat of urban Essex County. As of the United States 2000 Census, the city had a total population of 273,546, making it the largest municipality in New Jersey and the 65th largest city in the U.S. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city's 2004 population estimate is 281,402, an increase of 2.9% from 2000.

It is located approximately five miles (8.04 km) west of Manhattan and two miles north of Staten Island. Its location near the Atlantic Ocean on Newark Bay has helped make its port facility, Port Newark, the major container shipping port for New York Harbor. Together with Elizabeth, it is the home of Newark Liberty International Airport, which was the first major airport to serve the New York metropolitan area.

Newark was originally formed as a township on October 31, 1693, based on the Newark Tract, which was first purchased on July 11, 1667. Newark was granted a Royal Charter on April 27, 1713, and was incorporated as one of New Jersey's initial 104 townships by an act of the New Jersey Legislature on February 21, 1798. During its time as a township, portions were taken to form Springfield Township (April 14, 1794), Caldwell Township (February 16, 1798, now known as Fairfield Township), Orange Township (November 27, 1806), Bloomfield Township (March 23, 1812) and Clinton Township (April 14, 1834, remainder reabsorbed by Newark on March 5, 1902). Newark was reincorporated as a city on April 11, 1836, replacing Newark Township, based on the results of a referendum passed on March 18, 1836. The previously independent Vailsburg borough was annexed by Newark on January 1, 1905.[4] Newark is divided into five wards; North Ward, South Ward, West Ward, East Ward, and Central Ward.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Newark,_New_Jersey

The Official Website of the City of Newark, NJ

http://www.ci.newark.nj.us/

Newark, New Jersey

http://www.city-data.com/city/Newark-New-Jersey.html

Newark NJ Crime Statistics (2005 Crime Data)

http://newarknj.areaconnect.com/crime1.htm

History of Newark

http://www.ci.newark.ca.us/live/history.html

Newark. City (1990 pop. 275,221), seat of Essex co., NE N.J., on the Passaic River and Newark Bay; settled 1666, inc. as a city 1836. It is a port of entry and the largest city in the state. Located only 8 mi (13 km) W of New York City, Newark is a transportation, industrial, commercial, and manufacturing center. Its leather industry dates from the 17th cent., and its still-significant jewelry manufactures and insurance businesses began in the early 19th cent. Among the city's many other products are beer, cutlery, electronic equipment, textiles, pharmaceuticals, fabricated metal items, and paints. Newark International Airport is one of the nation's busiest, and the important seaport is operated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. The city has a large minority population; over 50% of its residents are African Americans and about 30% are Hispanic. Newark's educational institutions include a campus of Rutgers Univ., the New Jersey Institute of Technology, a campus of the Univ. of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, and a preparatory academy founded in 1774.

Landmarks include Trinity Cathedral (1810, with the spire of a church built in 1743); the Sacred Heart Cathedral (begun 1899, completed 1954); the First Presbyterian Church (1791); the Newark Public Library (founded 1888); the Newark Museum (1909); and the county courthouse (1906), with Gutzon Borglum's statue of Lincoln in front. Other points of interest include Borglum's large group Wars of America (1926) in Military Park (a Revolutionary War drilling ground and a Civil War tenting area) and many historic homes. Aaron Burr and Stephen Crane were born in Newark.

The city was settled (1666) by Puritans from Connecticut under Robert Treat. It was the scene of Revolutionary skirmishes. Industrial growth began after the American Revolution, aided by the development of transportation facilities. The Morris Canal was opened in 1832, and the railroads arrived in 1834 and 1835. A flourishing shipping business resulted, and Newark became the area's industrial center. In the late 19th cent. its industry was further developed, especially through the efforts of such men as Seth Boyden and J. W. Hyatt. Newark Port opened in 1915, and the city's shipbuilding played an important role in World War I.

During the latter half of the 20th cent., Newark's economy and living standards greatly declined. Many residents fled to the suburbs, which were marked by a boom in corporate development, shopping center growth, and housing construction. Poverty and unemployment plagued Newark, which in July, 1967, was the scene of a major race riot. Two bright spots have been the port, which since 1985 has had a steady increase in volume of exports of containerized cargo, and Newark International Airport, which has expanded greatly. As part of an effort to revitalize the downtown, the New Jersey Performing Arts Center opened in 1997.

http://www.answers.com/topic/newark-new-jersey?cat=travel

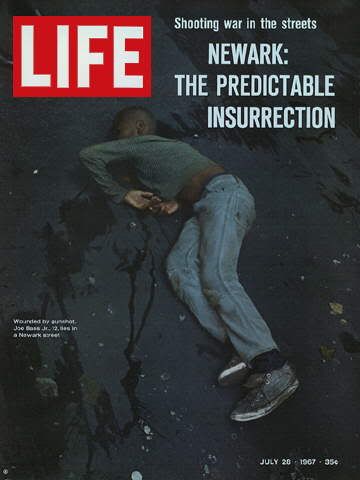

1967 Newark riots

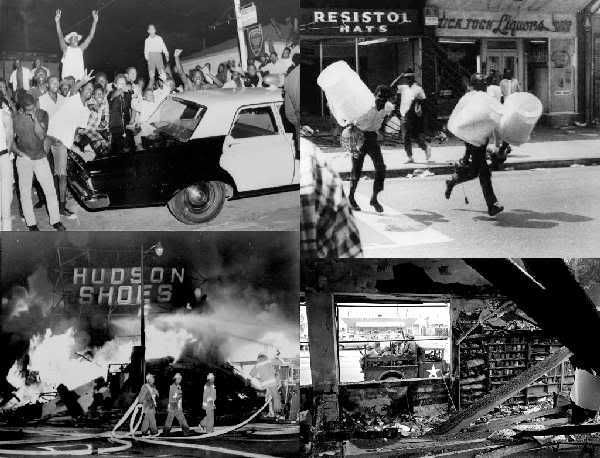

The 1967 Newark Riots were a major civil disturbance that occurred in the city of Newark, New Jersey between July 12 and July 17, 1967. In the period leading up to the riots, several factors led local African-American residents to feel powerless and disenfranchised. In particular, they had been largely excluded from political representation and allegedly suffered police brutality. Furthermore, unemployment, poverty, and concerns about low-quality housing contributed to the tinder-box.

According to a Rutgers University study on the riot, blacks had been disenfranchised in Newark despite the fact that Newark became one of the first majority black major cities in America alongside Washington D.C. Italian-American mayor Hugh Addonizio (who was also the last non-black mayor of Newark) failed to incorporate blacks in various civil leadership positions and to help blacks get better employment opportunities. The police department was dominated by Italian American and Irish American officers who would allegedly stop and attack blacks with or without provocation. Despite being one of the first cities in America to hire African American police officers, the department's current demographics did not adequately match the city's demographics leading to unrest between blacks and the police department. According to a legal essay, only 150 of the 1500 police officers (10 percent) were African American, while the city was over 50 percent African American.

This unrest came to a head when a black cab driver named John Smith was arrested for illegally passing a double-parked police car and allegedly beaten by police who accused him of resisting arrest. A crowd gathered outside the police station where he was detained, and a rumor was started that he had been killed while in police custody. (Actually he had been moved to a local hospital.)

This set off six days of riots, looting, violence, and destruction — ultimately leaving 26 people dead, 725 people injured, and close to 1,500 arrested. Property damage exceeded $10 million.

In an effort to contain the riots, every evening at 6 p.m. the Bridge Street and Jackson Street Bridges, both of which span the Passaic River between Newark and Harrison, were closed until the next morning.

The 1967 Plainfield riots occurred during the same period in Plainfield, New Jersey, a town about 18 miles southwest of Newark.

The riots were depicted in the Philip Roth novel American Pastoral.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1967_Newark_riots

Newark Riots..."At The Stadium"

40 Years On, Newark Re-Examines Painful Riot Past

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=11966375

Forty years ago this week, Newark, N.J., erupted into violence.

Newark was one of several cities across the country where riots broke out in the late 1960s. Years of poverty and discrimination had created a powder keg of frustration in many black communities. For Newark, the spark came on the hot summer night of July 12, 1967.

A black cab driver named John Smith was pulled over and badly beaten by the police. It happened within sight of the residents of a large public housing project. After Smith was dragged into the Fourth Precinct station house, an angry crowd quickly gathered outside.

Bob Curvin, an African-American resident of Newark, says that by the time he arrived, there were already a few hundred people milling around. Curvin was a civil-rights organizer at the time. He stood on a car to address the crowd, urging them to march downtown to protest the frequent brutality by the mostly white police force. But the crowd had lost patience with peaceful protests.

"There was a rain of stones, rocks, Molotov cocktails at the precinct," Curvin remembers. "The flames started flickering down the side of the building, and the police came charging out with night sticks, shields, riot gear, charging the crowd."

Curvin fled.

Chaos on the Streets

Five days of rioting followed. Stores were looted and some were burned down. After a policeman was killed, the governor sent in the National Guard with orders to use their weapons at will.

Reporters Ronnie Watkins and Bob Ortiz of Pacifica Radio followed the Newark police to an area near a hospital, where sporadic gunfire could be heard. "The whole scene is incomprehensible, absurd," they reported.

According to some residents, the National Guard used tanks and armored vehicles to block off streets, keeping many people from entering the city.

Craig Wilson grew up in the Jewish section of Newark and worked at his father's shop, Moe's Dry Goods. It was part of a row of small stores, owned mostly by white merchants, in Newark's black neighborhood, known as the Central Ward. When the riot ended, Wilson returned to the street. He says the area had been devastated.

"All the windows were shattered," he says of the neighborhood shops. "Some were burned out. Everything was stolen." Inexplicably, Wilson's father's store was the only one on the block left untouched.

According to official figures, 26 people died during the riots. More than 700 were injured, and there were 1,500 arrests. A governor's commission found that most of the deaths were caused by police or National Guard rifles.

But the causes of the riot went far deeper than one act of police brutality.

Frustration Fueled by Discrimination, Poverty

After World War II, whites began moving out of Newark to the suburbs in huge numbers, spurred on by new interstate highways, low-interest mortgages and widespread access to college provided by the G.I. Bill. As blacks moved into the Central Ward, they faced severe discrimination in jobs and housing.

William Linder, a white Catholic priest, came to Newark in 1963 as the city was undergoing these changes.

"There was no local home ownership — at all," he says. "School teachers were white. All the principals were white. The social workers were white."

"Even the rackets were controlled outside our community," he adds.

In the years since the riots, Linder has witnessed a number of changes in the neighborhood. City Hall and the police department are now mostly black-run institutions — but they struggle for the resources to do a good job.

Linder started and still runs a nonprofit organization that built housing and social service centers. It even brought the neighborhood its first supermarket in 25 years. And while home ownership rates are still low, there are owner-occupied homes in the Central Ward, some of them built by Linder's group.

Looking Forward Without Forgetting the Past

Today, outside the Fourth Precinct police station — ground zero for the events of 1967 — Newark's present meets its past.

"This community looks fundamentally different," says Rutgers University professor Clement Price. Forty years ago, "it was a walled-in neighborhood."

Now, instead of public housing towers, new townhomes stand across from the police station, offering home-ownership to low-income families. Price points to the front yards and the house numbers as examples of the American narrative arriving in this part of Newark.

"The Fourth Precinct reminds us of a Newark which I believe is part of a past and not a part of the future," Price says.

But Price doesn't want the past forgotten. He thinks the Fourth Precinct should be preserved as a landmark. His colleague, Rutgers sociologist Max Herman, agrees.

Herman is working on a book about the riots. He says that for most of the past 40 years, Newark has tried to ignore its history in favor of a message of renaissance. Herman believes that attitude held the city back, "because there hasn't been an honest airing of what happened in the past."

"You can't have a renaissance without reconciliation, and you can't have reconciliation without truth telling," Hermann says.

For the first time, many of the city's institutions are commemorating the riots. Herman is working on an exhibition at the New Jersey Historical Society. Another will be held at a contemporary arts center. The photos, video footage and oral histories will allow Newarkers to relive the riots. And the wide-angle lens that 40 years provides may just allow the kind of truth telling that Herman says the city needs.

Newark: A Brief History

From Puritan stronghold to industrial mecca to "Renaissance City," Newark, New Jersey, one of the poorest cities in the US, has undergone a series of radical transformations.

http://www.pbs.org/pov/pov2005/streetfight/special_overview.html

The city of Newark, New Jersey, was founded in 1666 by colonists looking to set up a Puritan theocracy. Newark's industrial boom began in the early to mid-1800s, when it was known for its leather factories and breweries. The construction of the Morris Canal and various railroads turned Newark into a bustling port city. Newark's insurance industry also took off in the mid-1800s, and today Newark remains the second leading seller of insurance in the nation.

Economic troubles, social strife, and other major problems developed for the city in the 20th century. The Great Depression brought on the start of Newark's urban flight, and manufacturers steadily left the city, taking their jobs with them. By the 1960s, Newark was a poor urban center surrounded by but disconnected from its middle class suburbs. As its white population shrank from 363,000 in the 1950s to 158,000 in 1967, its black population grew from 70,000 to 220,000 during the same period. The African American population had very quickly become the majority, and found itself concentrated in substandard housing projects and struggling with unemployment and political disenfranchisement. In 1967 racial tensions between the black community and the mostly white Newark police force led to disastrous riots, which ended in 26 deaths, 1,100 wounded, and $10 million in property damage. As the city continued its economic decline in the 1970s and 1980s the middle class population continued its exodus, leaving behind poor and polarized minority communities.

Newark Today

By 2003, the population of Newark had more or less stabilized and was estimated at 277,911. Thirty-one percent were living below the poverty line and the city's unemployment rate was 12 percent. Fifteen percent of people between the ages of 16 and 19 were high school dropouts. Nearly 60 percent of the population was African American, nearly 30 percent were Hispanic or Latino and 18 percent were white. Newark now contains the largest community of Portuguese immigrants in the US.

Newark is New Jersey's largest city and its industrial center. It is a major East Coast distribution and shipping hub and it is home to Newark Liberty International Airport, one of three airports that service New York City. Recent efforts at revitalization under the administration of Mayor Sharpe Jameshave included the 1997 opening of the New Jersey Performing Arts Center (NJPAC) and a minor league baseball stadium. However, areas like the Central Ward still suffer from high levels of crime and poverty. The latest major development plan for downtown is a $355 million arena for the New Jersey Devils hockey team.

Past Political Turmoil

Newark's political history is checkered with episodes of corruption. Although accusations of wrongdoing have trailed Mayor James's administration, the two mayors who preceded James set the stage with their own fair share of scandals.

Hugh Addonizio was mayor from 1962-1970. He was the son of Italian immigrants, a World War II hero who had served for 14 years in Congress prior to being elected as mayor. He ran on a reform platform, defeating what he characterized as the corrupt political machine of Leo Carlin, who had been mayor since 1953. Ironically, Addonizio was also accused of corruption. A state investigation into his administration on the heels of the 1967 riots led to the discovery that Addonizio and other city officials were taking kickbacks from city contractors. He was convicted on federal charges of extortion and conspiracy in 1970 and sentenced to ten years in prison.

Kenneth Gibson, Newark's first black mayor, was elected in 1970. Gibson won on a platform of reform. Before turning to politics, he had been an engineer, first for the state of New Jersey and then for Newark. He is credited with keeping Newark stable during his four-term administration, but, like Mayor Addonizio, he left office under suspicion of wrongdoing. During his last term he was indicted on state charges of conspiracy and misconduct but was eventually acquitted.

After leaving office, Gibson was involved in a scandal over a school construction project his engineering firm was managing. He was indicted on charges of bribery and stealing more than $1 million from the project. He also pleaded guilty in 2002 to one count of tax fraud, for which he received three years probation.

Sharpe James defeated Gibson in the 1986 mayoral race and is currently serving in his fifth term as mayor of Newark. He was elected to the city council in 1970 on the same spirit of reform and civil rights as Gibson, at a time when the city was still struggling to recover from the devastation of the 1967 riots.

In 1995 and 1996, James's administration experienced a series of scandals. Council President Gary Harris and Councilman Ralph T. Grant were both convicted of bribery. Chief of Police William Celester, who had been hand-picked by James, was convicted of using police funds for trips for his girlfriends. The biggest blow came when James's chief of staff and relative by marriage, Jackie Mattison, was convicted of bribery — he had been hiding $156,000 under the floorboards of his apartment. James survived these controversies and has been mayor of Newark for 19 years.

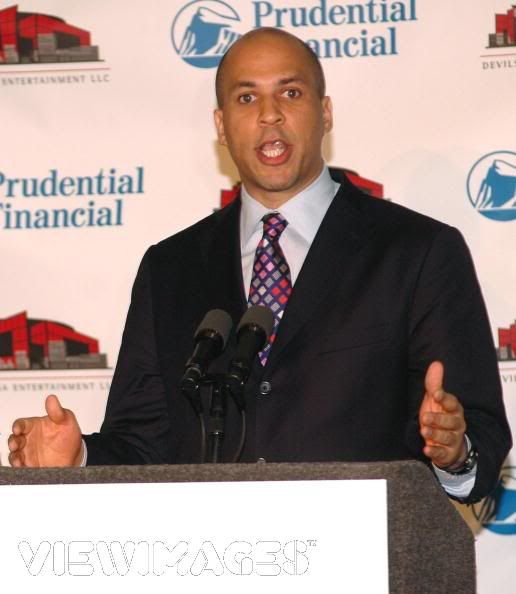

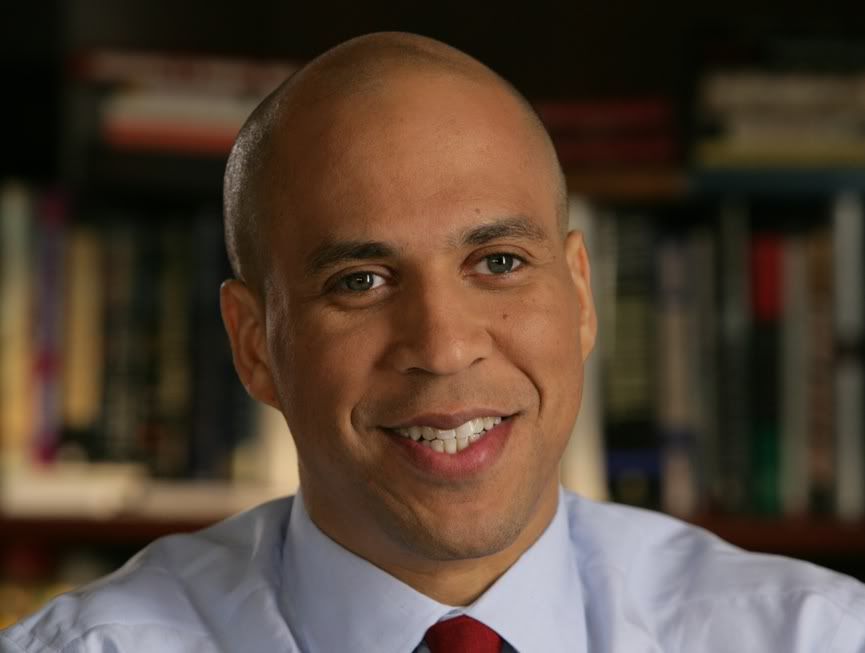

Cory Anthony Booker (born April 27, 1969) is the current Mayor of Newark, New Jersey. He is a Democratic politician and former Newark Councilman and community activist who ran unsuccessfully for mayor in 2002 against longtime incumbent Sharpe James. Booker ran again in 2006 and won a sweeping victory against Ronald Rice to become the 36th mayor of Newark. Booker is a graduate of Stanford, Oxford (as a Rhodes Scholar), and Yale Law School.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cory_Booker

Street Fight Trailer

Cory Booker Wins Newark's 'Street Fight'

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5446231

Next month, Cory Booker will officially become mayor of New Jersey's largest city, Newark. The 37-year-old Rhodes Scholar will have some monumental challenges to address.

Newark has been called the poorest city of its size in the United States, after Miami. The city's schools, already taken over by the state, are said to be barely functional, and crime is rampant.

But Booker, a former city councilman, has already been tested by fire in another way. It took him two campaigns to win the office. His first try in 2002, against incumbent Mayor Sharpe James, was called one of the nastiest contests in American politics.

Both Booker and James, the longest-serving mayor in the city's history, are Democrats and African American -- but that didn't stop James from making personal attacks against his opponent. The climate became so heated that the federal government sent in observers to watch for cheating and violence.

That election was captured in an Oscar-nominated documentary Street Fight, which portrays Booker as a young, idealistic politician pitted against an entrenched, old-school political machine that used any means necessary to crush opponents.

For the 2006 race, however, James pulled out of the race, saying he wanted to focus on his other elected position as a New Jersey State Senator. Booker easily bested his new opponent, state Sen. Ronald Rice.

Cory Booker

http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/people/b/cory_booker/index.html?inline=nyt-per

Cory Booker, 38, was elected mayor of Newark in May 2006, becoming only the third man to lead New Jersey?s largest city since 1970. A lawyer and Rhodes Scholar who previously served in the municipal council, Mr. Booker beat his opponent, State Senator Ronald L. Rice, with 72 percent of the vote. During the campaign, Mr. Booker pledged to tackle crime, widespread unemployment and the despair that has clouded this city?s fortunes since the 1967 riots drove thousands of residents to the suburbs.

Raised in the affluent suburb of Harrington Park and educated at Stanford University and Yale Law School, Mr. Booker and his charismatic style drew national attention to the city during his first unsuccessful run against Sharpe James, the 20-year incumbent. The rough-and-tumble battle between the two men in 2002 was captured in the documentary ?Street Fight,? which was nominated for an Academy Award.

Booker Comes Under Siege After Bloodshed

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/07/nyregion/07booker.html?em&ex=1186545600&en=12d793408ab92b0f&ei=5087%0A

NEWARK, Aug. 6 — As a weekend of bloodshed gave way to a day of mourning, the sleep deprivation and public battering were beginning to take a toll on Mayor Cory A. Booker, his face a curtain of sadness and fatigue. A group of protesters on the steps of City Hall were calling for his resignation, while a large huddle of reporters down the street waited with unanswerable questions about Saturday night’s fatal shooting of three college students in a West Ward schoolyard.

Moments before Mr. Booker was to step in front of the cameras, a mayoral aide noticed two middle-aged women and a man sitting silently among the crowd — relatives of Dashon Harvey, 20, one of the shooting victims. Officials quickly ushered them to a back room to meet Mr. Booker, who offered his condolences and promised that the police would stop at nothing to find the killers.

Then the mayor asked if there was anything he could do; during a pause, Mr. Booker seemed to be readying himself for a scolding.

“I just want to say that I don’t blame you for what happened,” said James Harvey, the young man’s father, his eyes teary. “I blame the parents in this city for not raising their children right.”

The two men hugged, and Mr. Booker, who lately finds himself blamed for everything that is wrong with New Jersey’s largest city, seemed greatly relieved. “I really admire you for your courage,” Mr. Booker said before heading to University Hospital to visit Natasha Aeriel, 19, the sole survivor of the shooting behind Mount Vernon School. “I could use a little bit of that right now.”

Thirteen months after galloping into City Hall on a promise to change the political climate and vanquish Newark’s reputation for violence, Mr. Booker finds himself at the nadir of his tenure, battling a homicide rate that refuses to yield and a growing tide of public hostility.

Although Garry F. McCarthy, his police director, frequently tries to remind the public that shootings are down 80 percent and that every other category of crime has dropped, Newark is just three body bags away from the 63 homicides tallied at this time last year, the highest in a decade.

It is worth noting that Mr. Booker held his news conference in the Police Department’s operations center, where 32 wireless surveillance cameras, installed two months ago, keep an eye on some of the city’s most lawless neighborhoods. But the new equipment and a strategic overhaul of the department have not reduced the steady drumbeat of killings.

“This hurts, this really hurts,” he said in an interview after meeting with the Harvey family, his voice wilted by exhaustion. “I still believe we’re going to move the city forward, but this is a powerful blow. This was going to be a summer we were going to brag about. This overshadows everything.”

The weekend’s four homicides — a man was killed in a separate attack not far from the Mount Vernon School on Sunday morning — come at a hard time for Mr. Booker, who is wrestling with a $180 million budget gap and the prospect of laying off as many as 400 city employees.

The slayings, and the ensuing flurry of media attention, followed a particularly bruising series of events that seemed to deeply shake City Hall.

Early last week, the city failed to pay 1,000 youngsters who were taking part in a summer jobs program that the mayor had promoted. When officials tried to make good, and summoned the teenagers to Newark Symphony Hall for payment, hundreds waited for hours in sweltering heat for the free pizza and soda that was meant to soothe them.

Then there was the YouTube incident. At a political fund-raiser in May, what Mr. Booker intended as an affectionate tribute to a Newark community advocate who had died a few months earlier was viewed as disparaging. He described the woman, Judith Diggs, as a portly hell-raiser who frequently cursed, and who was missing a few teeth. The home video rattled even his most ardent allies.

For both his enemies and his supporters, the episode seemed to crystallize a widespread sentiment here that Mr. Booker, who was raised in a manicured, largely white Bergen County suburb, is not entirely attuned to the culture and sensitivities of his constituents. Mr. Booker has apologized for the speech, but many are still feeling wounded.

“It was disgraceful,” said Dana Rone, a Municipal Council member and political ally of the mayor’s. “We need him to bring communities together, and I don’t think he displayed the leadership qualities we know he has.”

Ms. Rone spoke a few paces from a small group of protesters, their numbers dwarfed by a pack of reporters, who were ostensibly seeking an end to the senseless violence. But despite the placards calling for peace and unity, most at the rally outside City Hall on Monday were demanding the mayor’s ouster.

“He totally disrespects us,” said Donna Jackson, a frequent critic of the mayor, screaming into a megaphone. “He needs to pack his bags and go back to where he came from.”

Mr. Booker has long waved away such critics, saying they are surrogates for his political opponents or that they are seeking City Hall jobs that would buy their quiescence. Many of them, he points out, traffic in outlandish stories about the mayor.

“We have to use this as a pulling together, not a ripping apart,” he said about those using the killings to call for his resignation.

But he has clearly been rattled by the recent violence, and by the rising tide of people expressing disappointment in him. He said on Monday that he had not slept in 48 hours. On Monday morning, he returned to the scene of the shootings to speak to hundreds of children at a summer program at the Mount Vernon School, promising the students that such a brutal crime would not happen again.

Back at City Hall, Bertha Brooks, a teacher’s aide, stopped by to pay her taxes on Monday and ended up holding a “Stop the Violence” placard.

Ms. Brooks, 62, said she had been a Booker supporter but her ardor had been dimmed by rising crime, uncollected trash and the inattention of city officials when she calls to complain.

“I don’t care where Mr. Booker comes from,” she said. “As long as he gets the job done.”

Youth slayings rock New Jersey city

http://www.edmontonsun.com/News/World/2007/08/07/4398985-sun.html

NEWARK, N.J. -- In a city where gun violence has become an all too common part of daily life, these shootings were enough to chill even the most hardened residents: Four young friends shot execution-style in a schoolyard just days before they were to head to college.

Three were killed after being forced to kneel against a wall and then shot in the head at close range Saturday night, police said. A girl was found slumped near some bleachers about 10 metres away, a gunshot wound to the head but still alive.

The four Newark residents were to attend Delaware State University this fall. No arrests had been made by yesterday and authorities had not identified suspects.

The shootings ratcheted up anger in New Jersey's largest city, where the murder rate has risen 50% since 1998. The high number of killings have prompted billboards in the downtown area that scream, "HELP WANTED: Stop the Killings in Newark Now!"

"Anyone who has children in the city is in panic mode," Donna Jackson, president of Take Back Our Streets, a community-based organization. "It takes something like this for people to open up their eyes and understand that not every person killed in Newark is a drug dealer."

The killings bring Newark's murder total for the year to 60, and put pressure on Mayor Cory Booker, who campaigned last year on a promise of reducing crime.

A month ago, Booker and Police Director Garry McCarthy announced that crime in the city had fallen by 20% in the first six months of 2007 compared to a year ago. Yet despite decreases in the number of rapes, aggravated assaults and robberies, the murders have continued.

Natasha Aeriel, 19, was listed in fair condition at Newark's University Hospital. Police identified her slain companions as her brother, Terrance Aeriel, 18, Iofemi Hightower, 20, and Dashon Harvey, 20.

Authorities believe the shootings were a random robbery committed by several assailants and that some of the victims may have tried to resist their attackers. They were piecing together details of the attack from interviews with Natasha Aeriel.

Hightower and the Aeriels had been friends since elementary school and played in the marching band at West Side High School. Terrance Aeriel, known as T.J., took Hightower to the school prom in 2006, chauffeured by his sister.

At Delaware State they met Harvey, another musician, and struck up a friendship. Friends and family members said the four were not involved in drinking, drugs or gangs. They liked to congregate at the school, which sits in a middle-class neighbourhood less than two kilometres from the campus of Seton Hall University, to hang out and listen to music.

Fox news

Newark Slayings Shake Hardened City

Police Announce Arrest of Juvenile Suspect

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/08/09/AR2007080900417.html

NEWARK -- Amid the anger, tears and heartache over the recent execution-style killings of three college-bound young people here in Newark, there is also a sense of resignation that the slayings are an all-too-familiar part of everyday life.

"Murder is the norm," said resident Don Franklin, 49, who coaches youth football. "Just because these kids are college kids, it's getting more attention."

On Saturday night, in a schoolyard riddled with gang graffiti, three students were lined up against a wall, forced to kneel and shot in the head. A fourth survived after being shot near the ear.

[Based on information from the surivor, Newark police arrested a juvenile suspect early Thursday morning, the local Star-Ledger newspaper reported on its Web site. The paper attributed the information to unnamed sources close to the investigation. Local officials were expected to hold a press conference later this morning.]

Early Sunday morning, a man was shot and killed on Smith Street. And on Tuesday, a confrontation between an armed man and an off-duty corrections officer left the officer with a bullet wound in his foot and the other man dead from gunshots.

But the schoolyard killings have caused an outcry about the homicide rate, which remains stubbornly high despite the election of Mayor Cory A. Booker, who took office asking to be judged by his ability to reduce crime.

Other cities, including Boston, Philadelphia and Orlando, have in recent years experienced a spike in slayings after years of falling homicide rates.

In Newark, there have been 60 homicides this year. Last year at this time, 63 people had been killed, a number that grew to 105 by year's end, the highest total since the crack epidemic of the mid-1990s.

Every other category of crime has dropped this year, police are quick to point out, and violent crime is down 16 percent. Still, 61 percent of those recently polled by the Newark Star-Ledger said crime is the city's biggest problem -- up from 27 percent 10 years ago -- and 48 percent said if they had the money, they would leave town.

The harrowing story of last weekend's shooting could suggest why.

Four friends -- Iofemi Hightower, 20; Dashon Harvey, 20; Natasha Aeriel, 19; and Natasha's brother Terrance Aeriel, 18 -- had been listening to music and joking around behind Mount Vernon School on Saturday night. Authorities said that around 11:30, they sensed menace from others in the schoolyard and text-messaged one another that it was time to go home.

Instead, soon Natasha Aeriel was shot near the ear. Amid apparent struggle, the others were lined up at gunpoint against a low wall, shot in the head and killed. Natasha is in fair condition under police guard at University Hospital, where by Tuesday she was able to give information to investigators.

Police say they believe the motive was robbery. Lupe Todd, a spokesman for the mayor, would not comment after news reports suggested an arrest in the case was imminent.

Hightower and the Aeriels had been friends since elementary school in the Vailsburg section of Newark. They played together in the marching band at West Side High School and Terrance Aeriel, known as T.J., took Hightower to his prom last year, chauffeured by his sister. The group met Harvey more recently.

Two of them attended Delaware State University, and two planned to join them this fall.

The Aeriels lived in a white clapboard house, in a working-class neighborhood of homeowners.

But in Newark, where danger is block by block, nowhere seems far from burned and boarded-up buildings, weedy lots and half-standing fences, and what people here call "the war zones" of gangs.

The Aeriels' mother, Renee Tucker, has been rushing between visiting her daughter in the hospital and making funeral arrangements for her son.

"I will miss his smile, his funny face, the way he would make me laugh," she said on the phone of Terrance, who had been ordained as a minister.

India Lott, 18, a friend of Terrance's from his single semester last year at Delaware State, said she would tell him, "Newark is crazy!" He'd answer, "It's not worse than nowhere else."

"He had dreams of going to school and getting out of the ghetto," Ralpfe'ah Clark, 19, a close friend, said as she left a gilt-framed photo of them together, tied to red and silver balloons, at a memorial in the schoolyard where he had been killed. "He would say he can't stand to be around this environment," she said, recalling laughing loudly with Terrance in movie theaters, or stealing each other's shoes and then running barefoot into the street.

"They left this life in the worst way possible," said Clark, in tears.

But she, like half a dozen others interviewed for this article, could name other friends whose lives were cut off by gunfire, in a city where AK-47s, Glocks and .357 magnums are readily available for purchase or rent by the day.

"My friend was the 101st victim" of last year, said Ivette Calo, 34, who works for Verizon, adding that her neighbor was killed the year before that.

"I was a girl brought up in the street. Now I'm scared of the younger generation," she said.

In a dim apartment nearby, Kayron Harris, 17, Harvey's stepsister, said she has been full of fear since the killing of her stepbrother, a popular business major. "I don't go outside; I'm afraid to leave the house," she said.

James Harvey said that only a week before, he had picked up Dashon from college. Now he had just left a funeral home, where he had sat by his son's body and spoken his farewells.

"I said, 'Son, seeing you here is not what I imagined.' " Then he added, so painfully slowly that each word seemed like a separate sentence: "I will very much so miss him."

One Suspect Arrested in Brutal Newark Murders

Surviving Victim Has Helped Lead Police to Suspects, Says Mayor Cory Booker

http://www.abcnews.go.com/GMA/story?id=3462217&page=1

Police arrested a juvenile Wednesday night in connection with the execution-style slaying of three college students in a Newark, N.J., schoolyard, according to WABC-TV.

A formal announcement will come later today, Newark Mayor Cory Booker said on "Good Morning America."

Booker said that the information provided by the surviving victim, 19-year-old Natasha Aeriel, had helped lead the police to the suspect.

Sources tell WABC that Aeriel has identified a potential suspect. The man's fingerprint was found on a bottle at the murder scene, according to a report on WABC's Web site.

"We've got very strong ballistic evidence that we don't want to go into, but we do have evidence corroborating the information she's given us helping us track down people," Booker told "GMA."

"She's showing remarkable strength and courage, as all the families are," he said.

Snuffing out the 'Best of Newark'

For decades, Newark has been famous for having some of the deadliest streets in the nation. The shooting Saturday night seems to have delivered a body blow to the city and to its young, idealistic new mayor.

Three of the victims were forced to kneel against a wall and then shot in the head at close range, police said. Aeriel was found slumped near some bleachers 30 feet away with a gunshot wound to the head; she was still alive. She is listed in fair condition at Newark's University Hospital.

The anger and anguish in Newark is focused on both the cruelty of the crime and the promise of the victims.

"They were in college. They didn't live that lifestyle," said Renee Tucker, Aeriel's mother.

The four students were close friends who attended Delaware State College. Dashon Harvey, 20, was studying psychology; Iofemi Hightower, also 20, had just enrolled in college and was working two jobs. And Aeriel's brother, Terrence, 18, was studying business.

"I think it really was a body blow to all members of our city," Booker said. "We've been wrapping around the families especially because these children represented the best of Newark, the Newark that we want people to know about — that we have phenomenal kids here, the majority focused on doing the right thing."

The four victims were hanging out in a playground when police say they were approached by five young men. They started sending each other text messages on their phones saying they should leave.

Before they could leave, the men pulled guns and said it was a robbery, according to police.

"Young people out here armed to the gill and have no respect for human life, and they just kill one another at will," said Essex County Sheriff Armando B. Fontoura in a recent news conference.

In a community where pretty much everyone knows which gangs control which area, it cannot be easy to raise children, especially in a city now governed by fear.

But Booker, a Rhodes scholar who was elected mayor on his promise to rid the city of its violent past, said he still has hope. He calls the shootings a "defining moment" for the city.

"I really do believe that the crime is not going to define Newark, but our response to it," Booker said on "GMA."

"While there are a ton of practical things that must be done, the most important thing I see happening right now is our community is pulling together — Newarker to Newarker joining with businesses, clergy grass roots and nonprofits, all pulling together to say enough is enough and we're going to fight and win this battle."

Killings outrage U.S. city accustomed to crime

http://www.reuters.com/article/domesticNews/idUSN0834458820070808

NEWARK, New Jersey (Reuters) - In a city accustomed to violent crime, the execution-style killing of three promising young adults has delivered an especially cruel blow and tested an ambitious new mayor.

Newark, New Jersey, seemed bristling with confidence a month ago as police statistics showed crime was down and the city commemorated the 40th anniversary of its race riots with a message of hope for the future.

Today the mood is dark. Terrance Aeriel, 18, Dashon Harvey, 20, and Iofemi Hightower, 20, were lined up and shot in the back of the head on Saturday night in a primary school playground. Aeriel's sister, Natasha, 19, survived a bullet in the face.

By all accounts the four friends were good citizens who either attended or planned to attend Delaware State University.

Police are investigating the case as a robbery, but many neighbors are convinced it was some type of gang initiation.

"There was such a feeling of the city coming together. And unfortunately this throws a bucket of ice water over that," said Max Herman, a sociologist at Rutgers University in New Jersey, who is writing a book on the 1967 race riots that rocked Newark and Detroit.

The case has proved an acid test for Mayor Cory Booker, 38, who came into office a year ago asking voters to hold him accountable if he were unable to reduce crime.

"Unfortunately he has not been able to staunch the spate of violence in some neighborhoods. The expectations that the mayor articulated for himself were quite high," Herman said.

The city of 280,000 people about 10 miles west of New York is accustomed to crime.

At the Mount Vernon School where the killings took place, members of Newark's West Side High School football team took a break from summer workouts to pay their respects on Tuesday.

Virtually all were convinced the crime was gang related.

GANGS OF NEW JERSEY

Police estimate there are 20,000 to 30,000 members of 148 gangs in New Jersey, up from around 17,000 in 2004. About 40 percent of the state's homicides last year are believed to have been gang-related, up from 17 percent in 2004.

"If we hadn't gotten into the football life, these gangs would have gotten some of us," player Thomas Jones said from the schoolyard where the victims were gunned down, which was marked by candles and balloons.

"It could still happen," interjected another, Jonathan Quallis. "We're not all out of it yet."

On July 6, the mayor announced that in his first year in office crime was down 20 percent with a 6 percent reduction in homicides and a 30 percent reduction in shootings.

"But that's all overshadowed when something like this happens," Booker told WNYC radio. "I think everybody is really shaken by it."

With 60 murders so far this year compared to 63 at the same date a year ago, Newarkers say they don't feel safer. The 2006 homicide total of 105 was the highest in 16 years.

"It's obvious that I'm not to blame for this, but I'm taking personal responsibility. This is just not acceptable," Booker told reporters after the shootings. "This breaks the heart of our city."

Citizens and anti-crime groups are taking the mayor at his word and holding him to account.

"We expected things to get better. It seems that it is getting worse," said Joe Clitus, 62, an assistant teacher. "I believe the best thing is for people to leave town and go somewhere else. It seems we live in a jungle."

Football player Willie Morris agreed.

"I don't even want to live here anymore," Morris said. "I'm sick of Newark."

Newark NJ DEADLY VIOLENCE

STOLEN CARS IN NEWARK NEW JERSEY

Cruisin' in newark

![Brotherhood" (2006) [TV-Series]](http://photos1.blogger.com/x/blogger2/1421/379621144723082/211/z/425926/gse_multipart33129.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment