After 115 years, Lizzie’s legacy lives

http://www.heraldnews.com/homepage/x1802019498

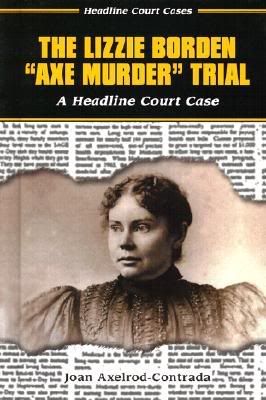

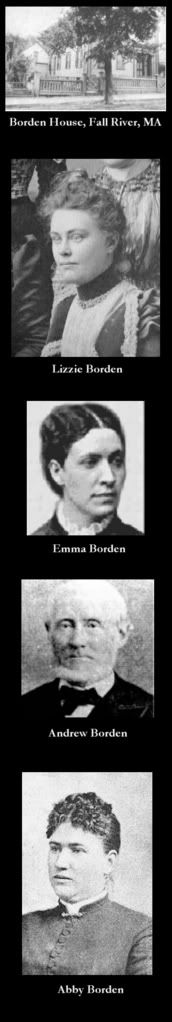

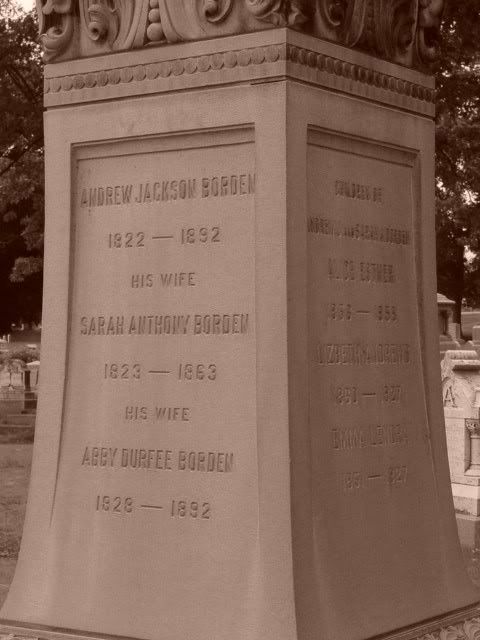

Today is the 115th anniversary of the grisly ax murders of Andrew Jackson Borden and Abby Durfee Borden, the father and stepmother of Lizzie Borden, who was — before this unsolved case — known as a socialite, spinster and Congregational Church Sunday school teacher.

After her accusal and acquittal however, Lizzie Borden became the most infamous woman in the United States and has inspired investigators, both amateur and trained, to try and solve the case of just who, if not Lizzie, murdered the wealthy businessman and his wife in their own home.

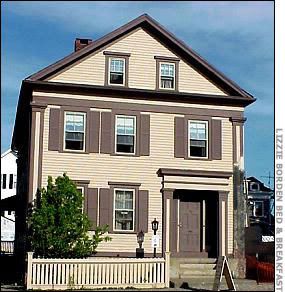

Today, the Lizzie Borden Bed & Breakfast, the site of the murders at 92 Second St., invite guests to a Victorian house of mourning from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. It will be a re-enactment of what the house might have been like one day after the killings. While the corpses of Andrew and Abby lay in the dining room, and the other women of the house, Lizzie, her sister Emma, her friend Alice, and the maid Bridget, prepare funeral cakes, discuss the happenings and mourn in their own way.

The Borden Murders of 1892

In 1892, Andrew and Abby Borden were axed to death in their home in Fall River, Mass. Lizzie Borden, Andrew Borden's daughter from a previous marriage, was accused of the killings, but acquitted at trial.

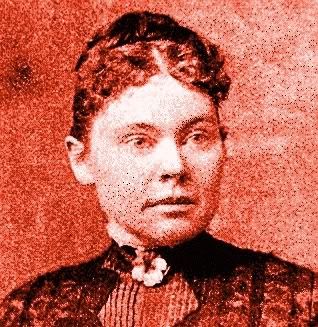

Lizzie Andrew Borden (July 19, 1860 – June 1, 1927) was a New England spinster who was the central figure in the axe murders of her father and stepmother on August 4, 1892 in Fall River, Massachusetts, in the United States. The slayings, trial, and the following trial by media became a cause célèbre, and the fame of the incident has endured in American pop culture and criminology. Although Lizzie Borden was acquitted, no one else was ever tried, and she has remained notorious in American folklore. Dispute over the identity of the killer or killers continues to this day.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lizzie_Borden

Lizzie Borden

http://www.answers.com/topic/lizzie-borden?cat=biz-fin

Lizzie Andrew Borden (July 19 1860 – June 1 1927) was a New England spinster and central figure in the brutal axe murders of her father and stepmother on August 4 1892 in Fall River, Massachusetts. Although acquitted, no one else was ever tried, and she has remained notorious in American folklore. The slayings, trial, and the following trial by media became a cause célèbre; and the fame of the incident has endured in American pop culture and criminology. Dispute over the identity of the killer or killers continues to this day.

The Murders

On August 4, 1892 Andrew J. Borden, Lizzie Borden's father, and her step-mother, Abby Borden, were murdered in the family home. The only other people present at the residence at the time were Lizzie and the family maid, Bridget Sullivan. An uncle, John V. Morse, (brother of Andrew Borden's first wife) was visiting at the time, but was away from the house during the time of the murders. Lizzie's older sister Emma was also away from home. That day, Andrew had gone into town to do his usual rounds at the bank and post office. He returned home at about 10:45. About a half-hour later, Lizzie found his body. According to Bridget's testimony, she was napping in the second floor of the house shortly after 11:00 am when Lizzie called up the stairs to her, saying someone had killed her father, whose body was found slumped on a couch in the downstairs sitting room. [1]

Shortly thereafter, while Lizzie was being attended to by neighbors and the family doctor, Bridget discovered the body of Mrs. Borden upstairs, in the guest bedroom. Mr. & Mrs. Borden had both been killed by blows from a hatchet, which in the case of Mr. Borden, not only crushed his skull but cleanly split his left eyeball. [1]

Motive and method

Study of the facts in the case reveals that over a period of years since the death of the first Mrs. Borden, life at 92 Second Street had grown unpleasant in many ways, and that affection among the older and younger family members had waned considerably if any was present at all. The upstairs floor of the house was divided -- the front being the territory of Lizzie and her sister Emma, and the rear that of Mr. and Mrs. Borden. Meals were not always taken together, and conflict had come to a head between the two daughters and their father about his decision to divide up valuable property among relatives before his death -- a house had been turned over to relatives of their stepmother, and Uncle John Morse had come to visit to facilitate transfer of farm property which included what had been a summer home for the Borden daughters that week. Shortly before the murders, a heated argument had taken place which resulted in both Emma and Lizzie leaving home on extended "vacations"—- Lizzie, however, decided to cut her trip short and return early.

She was refused the opportunity to purchase cyanide by a local druggist, which Lizzie claimed was for cleaning a seal skin coat. Shortly before the murders, the entire household—- Lizzie included—- took violently ill. As Mr. Borden was not a popular man in town Mrs. Borden feared they were being poisoned but the family doctor diagnosed it as bad food.

Lizzie's testimony as given at the original inquest incriminated her several ways.

The Trial

Lizzie's stories proved to be inconsistent, and her behavior suspect. She was tried for the murders, defended by former Massachusetts Governor George Robinson.

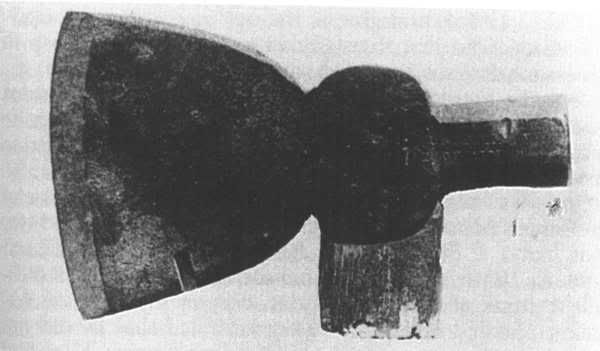

During the police investigation, a hatchet was found in the basement and was assumed to be the murder weapon. Though it was clean, most of its handle was missing and the prosecution stated that it had been broken off because it was covered with blood. However, police officer Michael Mullaly stated that he found it next to a hatchet handle. Deputy Marshall John Fleet contradicted this testimony. Later a forensics expert said there was no time for the hatchet to be cleaned after the murder.[1]

No blood-soaked clothing was ever taken as evidence by police. A few days after the murder, Lizzie tore apart and burned a light blue Bedford cord cotton dress in the kitchen stove, claiming she had brushed against fresh baseboard paint which had smeared on it.

Despite incriminating circumstances, Lizzie Borden was acquitted by a jury after an hour's deliberation. The fact that no murder weapon was found and Lizzie was clear of blood just a few minutes after the second murder pointed to reasonable doubt. Some blame the fact that her entire original inquest testimony was barred from the trial, as was evidence she attempted to purchase cyanide from a local drugstore days before the murders took place, for her acquittal. Others have suggested the all-male jury did not like the idea of acknowledging that a respected man's daughter could possibly have committed such an act. Certainly, another axe murder in the area which took place shortly before the trial was a great stroke of luck for Lizzie. [1]

Conjecture

Several theories have been presented over the years suggesting Lizzie may not have committed the murders, and that other suspects may have had possible motives. One theory was that Lizzie was having a lesbian affair with the maid and was discovered by her step-mother. Another was that any number of townspeople could have carried out a grudge against Mr. or Mrs. Borden. Another theory is that the maid did it, possibly out of outrage for being asked to clean the windows, a backbreaking job on a hot day, just a day after having suffered from food poisoning. Yet another theory is that Lizzie suffered petit mal epileptic seizures during her monthly period, at which times she entered a dream-like state, and unknowingly committed the murders then.[1]

Sullivan allegedly gave a deathbed confession to her sister, stating that she had changed her testimony on the stand in order to protect Lizzie.[1]

Public reaction

The trial received a tremendous amount of national publicity, a relatively new phenomenon for the times. It has been compared to the later trials of Bruno Hauptmann and O.J. Simpson as a landmark in media coverage of legal proceedings.

The case was memorialized in a popular jump-rope rhyme:

Lizzie Borden took an axe

And gave her mother forty whacks.

And when she saw what she had done

She gave her father forty-one.

The anonymous rhyme was made up by a writer as an alluring little tune to sell newspapers even though in reality her stepmother suffered 18[2] or 19[1] blows, her father 11. Though acquitted for the crimes, Lizzie Borden was ostracized by neighbors following the murders.[1] Lizzie Borden's name was again brought to the public forefront when she was accused of shoplifting several years following the murders.

Alleged affair with actress Nance O'Neil

In 1904, actress Nance O'Neil met Lizzie Borden in Boston. In the early 20th century, it was still considered socially unacceptable for women to become actresses. O'Neil was a spendthrift, always in financial trouble, and Borden came from a wealthy background. The two had an intense relationship, despite Borden's notoriety. O'Neil was married at the time.

While it has never been definitively proven that the two were intimate, the termination of the relationship two years later in 1906 was a significant loss to Borden, and she is alleged to have had difficulty in recovering emotionally. O'Neil was later a character in the musical about Lizzie Borden, entitled Lizzie Borden: A Musical Tragedy in Two Axe, where she was played by Suellen Vance. Feminist Carolyn Gage refers to O'Neil as an overt lesbian[1], and although there are few documented details of any affairs other than Borden, Gage claimed that her sexual orientation was well known in entertainment circles, despite her marriage. The book Lizzie by Evan Hunter (real name Salvatore Lombino, and also famous for writing under the name Ed McBain) is the chief source of this conjecture.

Legacy

The house on Second Street where the murders occurred is now a bed and breakfast. It is open for daily tours. When the house was renovated some years ago by a previous owner, at least one hatchet was found. It was given to the police. Nothing came of it. Ongoing work has restored the home to a close approximation of its 1892 condition.

"Maplecroft," the mansion Lizzie bought after her acquittal, on then-fashionable French Street in the "highlands" is privately owned, and only occasionally available for touring.

Genealogy

Borden was distantly related to the American milk processor Gail Borden (1801-1874), Robert Borden (1854-1937), Canada's Prime Minister during World War I, and the late US actress Elizabeth Montgomery (1933-1995) who had also portrayed her life story in the 1975 movie.

Did she murder her father & stepmother?

http://www.crimelibrary.com/notorious_murders/famous/borden/index_1.html

Lizzie Borden Virtual Museum and Library

http://www.google.com/search?num=50&hl=en&safe=off&q=lizzie+borden&btnG=Search

Lizzie Borden Bed and Breakfast

http://www.google.com/search?tab=nw&hl=en&q=lizzie%20borden

How to Tour the Lizzie Borden House

http://www.ehow.com/how_2052491_tour-lizzie-borden-house.html

The Trial of Lizzie Borden: Selected Newspaper Articles

http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/LizzieBorden/bordenarticles.html

The Trial of Lizzie Borden

http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/LizzieBorden/bordenhome.html

Lizzie Borden (1860 - 1927) - Find A Grave Memorial

http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=115

The Borden Trial: Biographies of Key Figures

http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/LizzieBorden/biographiesborden.html

Lizzie Borden's Timeline

http://www.lizzieandrewborden.com/CrimeLibrary/ChronologyLizzie.htm

Source: Lizzie's testimony at the Inquest held from August 9 - August 11, 1892

Inquest Upon the Deaths of Andrew J. and Abby D. Borden, August 9 - 11, 1892, Volume I and II. Fall River, MA: Fall River Historical Society.

Aug. 4, 1892, Thursday

8:45 - 8:50 a.m.

Lizzie comes down "a few minutes before nine." "I should say about a quarter" [before nine]. (pg. 56, 59).

Saw "Maggie" [Bridget] and Mrs. Borden; Morse "was not there." (pg. 56).

The family had already breakfasted.

Spoke to her father, and Mrs. Borden . . . "spoke to them all."

Did not mention Morse, nor inquire anything about him. (pg. 56).

"When I first came down stairs I went down cellar to the water closet." (pg. 63).

Mr. Borden was in the sitting room reading the paper. (pg. 58).

Mrs. Borden was in the dining room dusting. (pg. 58).

9:00 a.m.*

Mrs. Borden had left the guest room "all in order". (pg. 63).

She was going to put some fresh pillow slips on the small pillows at the foot of the bed and was going to close the room . . . "

"She had done that [made bed, dusted, etc.] when I came down."

It would take "about 2 minutes" to put on the pillow slips. (pg. 63).

Did not see her after Lizzie "went down in the morning and she [Mrs. Borden] was dusting the dining room." (pg. 62).

"I left her in the dining room." (pg. 62).

"I should have seen her if she had stayed down stairs; if she had gone to her room I would not have seen her." (pg. 63).

Mrs. Borden could have gone to her room while "I was down cellar." (pg. 65).

Lizzie did not see Mrs. Borden when Lizzie came back from down cellar. (pg. 65).

"I had supposed she had gone out." (pg. 66).

Lizzie gone [down cellar] a little more than 5 minutes. (pg. 66).

"Maggie" had "Just come in [while Mrs. Borden dusted the D. R.] the back door with the long pole, brush . . . she was going to wash the windows around the house. She said Mrs. Borden wanted her to." (pg. 58).

Lizzie did not have any coffee or tea; does not know if ate any cookies. (pg. 59).

When she got down the breakfast things were all put away "except the coffee pot; I am not sure if that was on the stove or not." (pg. 59).

The next thing that happened after Lizzie got down was "Maggie went out of doors to wash the windows . . . " and Mr. Borden "came out into the kitchen and said he did not know whether he would go down to the post office or not. And then I sprinkled some handkerchiefs to iron." (pg. 59).

"Maggie" went out after the brush before Mr. Borden went away. (pg. 59).

"After 9 o'clock"

"It must have been after 9 o'clock" when Mr. Borden went down town. (pg. 60).

"I was in the dining room . . . [when Mr. Borden started away] . . . I had just commenced . . . to iron." (pg. 59).

"About 10 a.m."

"My father did not go away . . . until somewhere about 10." (pg. 68).

Lizzie "had not commenced [to iron handkerchiefs], but [I] was getting the little ironing board and the flannel." (pg. 60).

Before Mr. Borden returned, Lizzie did not see "Maggie". (pg. 67).

After Mr. Borden went out Lizzie did not go up stairs at all. (pg. 67).

Lizzie carried some clean clothes up. (pg. 60).

Stayed "in my room long enough when I went up to sew a little piece of tape on a garment." (pg. 60).

The door to the guest room was closed. (pg. 64).

"He [Mr. Borden] came home after I came down stairs." (pg. 60).

"I think "Maggie" let him in." (pg. 61).

"After 10:00 a.m."

"It must have been after 10 [when he came home] because I think he told me he did not think he should go out until about 10." (pg. 83).

"He was not gone so very long." (pg. 84).

When the bell rang "I think [I was] in my room up stairs." (pg. 61).

"I was on the stairs coming down when she ["Maggie"] let him in."

"I don't think I had been up there over 5 minutes" [when Mr. Borden returned]. (pg. 61).

Mr. Borden was gone "not very long." (pg. 62)

"I was down in the kitchen . . . [when he returned] reading an old magazine" . . . "eating a pear." (pg. 60, 68).

"I am not sure whether I was there [kitchen] or in the dining room." (pg. 60).

Lizzie was in the kitchen when her father was let in. (pg. 67).

Lizzie was reading an old magazine "for perhaps 1/2 an hour" before going to the barn. (pg. 71).

After Mr. Borden came home Lizzie was in the sitting room with him. (pg. 66).

Lizzie did not iron any more after he came in. (p. 68).

Lizzie swears she did not see him go up stairs (to his room). (pg. 84, 85).

Lizzie did not see "Maggie" after she let Mr. Borden in. (pg. 69).

Lizzie "might have seen her ["Maggie"] and not know it." (pg. 70).

Lizzie doesn't know when Mr. Borden came home. (pg. 69).

Lizzie went right out to the barn-not less than 5 minutes [after Mr. Borden returned]. (pg. 84).

Lizzie got some pears first. (pg. 72).

Lizzie stayed under the pear tree 4 or 5 minutes. (pg. 88).

Lizzie was 15 or 20 minutes in the barn "trying to find lead for a sinker", and ate pears. (pg. 69, 77).

15 or 20 minutes after Mr. Borden came home Lizzie found him on the sofa. (pg. 69).

Mr. Borden was lying down on the sofa. (pg.78).

Lizzie noticed that he had been cut.

Lizzie..."did not see his face, because he was all covered with blood." It made her "afraid."

Lizzie called "Maggie" and told her Mr. Borden was "hurt."

Lizzie did not know whether or not he was dead.

Lizzie did not search for Mrs. Borden.

Lizzie thought Mrs. Borden was out.

Lizzie sent "Maggie" for Dr. Bowen. (pg. 78).

*(pg.80)

Questioning by Knowlton:

Q: "Miss Borden, I want you now to tell me all the talk you had with your mother, when you came down, and all the talk she had with you. Please begin again."

A: "She asked me how I felt. I told her. She asked me what I wanted for dinner. I told her not anything, what kind of meat I wanted for dinner. I told her not any. She said she had been up and made the spare bed, and was going to take up some linen pillow cases for the small pillows at the foot, and then the room was done. She says: "I have had a note from somebody that is sick, and I am going out, and I will get the dinner at the same time." I think she said something about the weather, I don't know. She also asked me if I would direct some wrappers for her, which I did."

Lizzie Borden’s Father and Stepmother Murdered

http://www.massmoments.org/moment.cfm?mid=226

...in 1892, a prosperous banker and his wife were hacked to death with a hatchet in their Fall River home. Suspicion immediately focused on the man's unmarried 32-year-old daughter, Lizzie Borden. Basing their case entirely on circumstantial evidence, police indicted her for murder. Newspapers all over the country carried sensationalized, sometimes completely fabricated, stories. When she came to trial the following June, the nation was mesmerized by the spectacle of a Sunday-School-teaching maiden lady charged with committing such gruesome crimes. But the prosecution's case was badly flawed, and after a two-week trial, the jury found Lizzie Borden not guilty. She would never be free from suspicion, however, and lived the rest of her life as a social outcast.

"Lizzie Borden took an ax and gave her mother 40 whacks. And when she saw what she had done, she gave her father 41." For over a century, this rhyme has perpetuated the notion of Lizzie Borden as a hatchet-wielding, cold-blooded murderer. Yet it took a jury less than an hour to find the 33-year-old Fall River woman not guilty.

There is no doubt that a horrible crime was committed. Lizzie's father, Andrew, and her stepmother, Abby, were killed in their own home by multiple blows with an axe; their skulls were crushed and mutilated to the point where they were barely recognizable. Astonishingly, given that it was between 9:30 and 11:00 am and that Lizzie and the family maid Bridget were both at home, no one either heard or saw anything amiss.

Within minutes of her father's murder, Lizzie entered the parlor and discovered his body. Distraught, she immediately sent Bridget for a doctor and called in a neighbor who summoned the police. Shortly afterwards, the neighbor discovered Mrs. Borden's body in an upstairs room.

When the police arrived, they questioned Lizzie. She told them that Bridget had been upstairs washing windows and that she had gone to get something from the barn, returning a half-hour later to find her father's mutilated corpse. When the officer asked about her mother, the traumatized Lizzie snapped, "She is not my mother. She is my stepmother." From that moment on, Lizzie Borden was the chief — indeed, the only — suspect in the case.

According to police, she was a bitter, jealous daughter who hated her stepmother and killed her father to prevent him from changing his will to benefit his wife at the expense of his daughter. When a local druggist said that Lizzie Borden had tried unsuccessfully to purchase poison from him the day before the murders and a neighbor reported that she had seen Lizzie burning a dress several days after the murders, the police decided they had enough evidence to charge her.

The American public was enthralled by the case. Newspapers printed gruesome, often embroidered — or patently false — stories that transformed a respectable, churchgoing, socially-active young woman into a monstrous fiend. The contrast between the bloodiness of the acts and the genteel setting in which they took place added to the public's fascination.

The prosecution's case began to unravel almost as soon as the trial opened. There was not a spot of blood on the dress Lizzie Borden was wearing when she was found at the blood-spattered murder scene. There were problems with the murder weapon, too, and Andrew Borden's personal attorney had no knowledge that his client had ever made a will.

The defense showed that the burned dress was a faded and paint-stained one that Lizzie's sister had advised her to get rid of; burning was the family's normal method of disposing of trash. The defendant swore under oath that the druggist was mistaken; she had not visited his shop and she had not requested poison from him. The state was unable to produce a convincing motive, a murder weapon, or an explanation for how the young woman could have committed the bloody murders and appeared only moments later wearing a spotless dress.

The verdict was greeted with jubilation in the courthouse, and most newspapers agreed that Lizzie Borden should never have been tried. But the Fall River Police Department announced that it would not pursue other leads; it considered the case closed. The implication was clear: the police believed the murderer had been acquitted.

The question remained: who did kill Andrew and Abby Borden? Doubts and rumors persisted, and the once respectable Miss Borden found herself ostracized by Fall River's polite society. For many years, August 4th gave the more sensational press the chance to sell papers by reviving the unsolved crime and raising questions about the case all over again. With each passing year, the jury's verdict seemed to fade into history. By the time she died in 1927, Lizzie Borden was firmly fixed in popular culture as the perpetrator of one of the nation's most notorious and mysterious crimes.

The Guest Room, The Scene of the Murder, Lizzie Borden

How Lizzie Borden Got Away With Murder

http://crimemagazine.com/borden.htm

The New York Times headline for Aug. 5th, 1892 read: "BUTCHERED IN THEIR HOME: Mr. Borden and His Wife Killed in Broad Daylight." The first paragraph of the stunning article read:

FALL RIVER, Mass, Aug. 4 -- Andrew J. Borden and wife, two of the oldest, wealthiest, and most highly respected persons in the city, were brutally murdered with an ax at 11 o'clock this morning in their home on Second Street, within a few minutes' walk of the City Hall. The Borden family consisted of the father, mother, two daughters, and a servant. The older daughter has been in Fair Haven for some days. The rest of the family has been ill for three or four days, and Dr. Bowen, the attending physician, thought they had been poisoned.

The horrific axe murders of Andrew Borden and his second wife, Abby, would have been shocking in any age, but in the early 1890s they were unthinkable. Equally unthinkable was who wielded the axe that butchered them an hour or so apart in their own home. The idea that the murderer could possibly be Borden’s 32-year-old daughter Lizzie took days to register with the police – despite overwhelming physical and circumstantial evidence that pointed only at her. Nine months later a jury, unable to fathom that a woman could commit such vicious crimes, would find a way to ignore the evidence and set Lizzie free.

By no means had Lizzie Borden committed the perfect crime. The police were quickly able to dispense with the possibility of an outside intruder carrying out the murders. Lizzie – her alibi fraught with inconsistencies – was the only suspect. She alone had both the motive and the opportunity. What would end up saving her was the remarkable violence of the murders: The murders were simply too grisly to have been committed by a woman of her upbringing.

The Borden mystery is captured within a web of falsified statements, suppositions, assumptions and public opinion, all of which revolve around a missing weapon that actually never was missing, a blood-stained dress that was never found, and a young woman’s previously impeccable character.

Even today, crime historians remain divided about Lizzie’s guilt. The viciousness of the murder scene did contrast sharply with the image of Lizzie: a civilized, upper-middle-class woman who had never married and who had lived at home her entire life.

The Borden Family

Lizzie’s father, Andrew Borden, was originally an undertaker. Even then he was known to be stingy and tight-fisted, and rumors floated about town that he forced corpses into coffins with bent knees to save on the cost of wood. Later he would become a bank president and a mill director. Financially well off for the time period, his net worth figured at over $300,000. Instead of making his home on "the hill," where the community’s financial elite resided, the Bordens lived on Second Street in Fall River in a starkly furnished house that featured kerosene lamps and two running cold-water faucets. The only toilet was in the cellar, but it was rarely used. Instead each room had a chamber pot that was emptied in the morning into a slop pail that was in turn emptied onto the back lawn. Andrew’s reputation in town, whispered of course, was that of Scrooge.

The dreary Borden household consisted of Andrew, his second wife, Abby, his two adult daughters, Emma and Lizzie, and a maid, Bridget Sullivan. In a book entitled A Private Disgrace, author Victoria Lincoln depicted the atmosphere in the Borden home as one of strained civility: neither Emma nor Lizzie liked their stepmother, an overweight recluse who rarely left the house. Abby, in turn, thought little of her stepdaughters. And Andrew? He didn’t seen to care. He barely maintained a tenuous peace by bribing Lizzie with a lavish spending account, for no one, not even Andrew, cared to upset the moody Lizzie

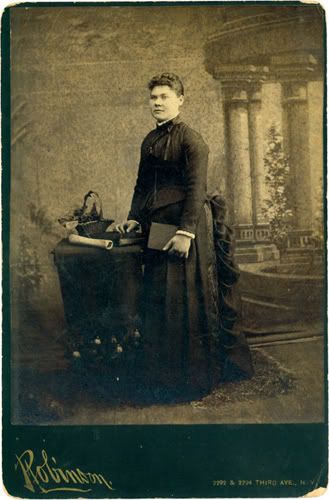

Lizzie was a self-conscious woman with reddish-brown hair and extremely light blue eyes. Wide shouldered with a thick waist, she was cursed with a coarse, sallow complexion and rather heavy jowls. Her manners, though, were impeccable: She was polite to hired help and to anyone she met, and was known for her kindness to animals. While she was socially handicapped and made few friends, it could not be said that these traits were caused by an evil or especially disagreeable temperament. Though Lizzie was known to be a conversationalist, she did tend to sulk, refusing to speak to someone for days, if she felt angered or offended. She may have suffered from migraines, as her mother did before her, and on several occasions her close relatives and acquaintances spoke of her ‘spells’. That her spells nearly always coincided with her monthly menstrual cycle was not something that was understood in 1892. In any regard, no one spoke of such matters and the common belief was that women suffering spells were almost always ‘crazy’.

The author Lincoln further suggests that Lizzie suffered from what is now known as ‘temporal epilepsy’. It’s doubtful such a claim could be scientifically proved, but that Lizzie suffered from occasional "brownouts" is verified in both her police and court records. Still the fact remains, that for two weeks prior to the murders, Lizzie had attempted to purchase prussic acid – supposedly to use on Abby. Being a well brought up young woman, Lizzie was unaware that arsenic was available over the counter, without a prescription, as was required for prussic acid.

The Crime

The murders occurred at the Borden home on a sweltering summer morning, Thursday, Aug. 4, 1892. By mid-morning, the family members and maid were about their chores; Abby was busy feather dusting while Andrew readied to go downtown. On his way out, Andrew passed Bridget, the maid, as she began to wash the windows, starting with the outside. Lizzie, claiming an upset stomach, wandered aimlessly about. Emma, the older sister, was away visiting, and their overnight guest, Andrew’s brother-in-law from his deceased first wife, had left to visit his niece.

Andrew normally remained downtown to take care of business and collect his rents until around noon, when he would return home for dinner. But on this day, he came home an hour and a half early. He first sat down in the dining room, and then after making himself a bit more comfortable, moved into the sitting room to avoid Bridget’s window cleaning. He reclined on the sofa with his legs from the knees down dangling off the edge. Abby, who almost always spent her mornings downstairs, did not appear when he came home. Instead, Lizzie came down, dressed in a heavy bengaline silk dress, an outfit consisting of a navy blue skirt with pale blue print and a separate blouse. Such a heavy dress was an odd choice on a day when the temperature had already risen to 89 degrees by 7:30 in the morning. According to proper etiquette at the time, women wore a ‘street’ dress only for going out. Was Lizzie on her way downtown to establish an alibi but was prevented from doing so by Andrew’s unexpected early return?

Bridget, her chore completed but not feeling well, came inside and went up to her room to lie down. Bridget was awakened a short while later by Lizzie’s shout that her father was dead.

Andrew’s body was found on the sofa where he had fallen asleep, right cheek resting on a cushion and an afghan he had propped beneath his head. Though his face tilted upward, what remained of it was nearly unrecognizable as human: One eye had been cut in half and protruded from its socket, his nose had been severed and 11 gaping gashes concentrated upon the left side of his face. Andrew’s blood still ran bright and fresh as police arrived. There is little doubt that he more than likely never knew what hit him.

Confusion reigned. First doctors were summoned and then the police. During the minutes immediately following the discovery of Andrew’s lifeless body, doctors, police and neighbors came in and then left again. A short time later, Lizzie remarked on Abby’s absence and suggested that someone might want to look for her. Abby was found upstairs in the guest room, lying face down in a pool of blood, her head nearly separated from her shoulders by a blunt instrument. Because of the location of one of the wounds, forensic experts surmised she might have seen her attacker as the first blow was delivered. Upon further examination, Dr. Bowen discovered her head had been nearly crushed by 19 axe or hatchet wounds in the back of the skull. One wound at the back of the neck was misdirected, the blow cutting a flap of skin from the back of her scalp. Because of a lack of blood splashes on nearby walls or furniture, it became common conjecture that Abby died from the first blow; her heart stopped pumping blood, thereby resulting in very little blood spatter for such horrific wounds.

The Evidence

The police instructed the maid to show them any axes or hatchets the Bordens used on the property. She brought several up from the cellar, one coated with dried hair and blood (which later proved to belong to a cow). From the fruit cellar she produced a claw headed hatchet stained with rust. She then produced a box from the cellar that contained two hatchets, both covered with a layer of fine dust.

Because Abby’s blood had already turned thick and coagulated, the police, with the aid of the doctor’s expertise, were certain that Abby had been murdered at least an hour before Andrew. But how could the murderer have escaped the house undetected? The front door remained bolted and locked from the inside. Lizzie claimed she had been in the yard but then changed her location to the barn. Either way, the police did not think it likely that the murderer could have escaped out the back door without her seeing him.

Abby had been hacked by someone who probably had stood straddled over the body after the initial blow had knocked her down. Her blood splashed forward, but not very high or wide, and only one tiny spot of blood stained the bedspread beside her. The wall in front of her sustained little spatter, and that limited to the baseboard. Common consensus among the police was that the murderer need not have been splattered by much blood in such a scenario, that perhaps only the area below the knees would be prone to blood splatter.

Very little blood spatter marked the walls in the sitting room either. Andrew’s blood had dripped onto the carpet, but no blood spattered the small table near his head. On the wall behind the sofa, there was some evidence of splatter in the shape of little pearl drops. One policeman then noticed that Andrew’s Prince Albert coat appeared wadded up beneath his mangled head, crammed between the sofa and pillow. Yet anyone who knew Andrew knew he would never treat his coat to such abuse. It is entirely possible that the murderer slipped the coat off the rack and put it on so that it would catch the blood splatters and then shoved it beneath his head to account for the blood splatters on it.

A short time later, the police reexamined the box of tools and axes that had been tucked on the ledge near the chimney in the cellar. In it they found a hatchet head – not dusty like the other two – but covered with what appeared to be white ashes in what police considered a possible attempt to disguise it to look similar to the others or a failed attempt to melt it down. Although it was a sweltering August day, a blazing fire was in progress in the kitchen stove.

It was the house itself that spoke so strongly against Lizzie’s claim that someone from outside the house murdered her parents. Six people lived in the cramped two-and-a-half story home with interconnecting doors and thin walls. It would have been difficult to stifle the sound of a scream or the crash of overweight Abby as she fell to the floor upstairs.

The Fall River police checked the house and found the front door, the back screen door, the basement door and most of the bedroom doors locked. To give the police their due, they made a determined attempt to eliminate any possible outside suspects before considering the distant possibility of the murders being an inside job.

Lizzie claimed that she had last seen her father falling asleep in the sitting room. She then claimed she had spent some time in the barn loft, but an officer who went to look at the loft found no evidence of her having been there. Dust laid thick and undisturbed upstairs in the loft, not to mention the heat made the place almost unbearable.

As the bodies lay under sheets in the dining room, one of the doctors performed a partial autopsy while a five-man team thoroughly searched the house from attic to cellar. They found nothing else to indicate the identity of the assailant. The broken handle of the axe was never found, nor was any blood found in any of the other remaining rooms.

Perhaps it was inevitable that Lizzie would become the prime suspect, especially after the police learned she had made several unsuccessful attempts to buy prussic acid during the two previous weeks. And then there was the persistent problem of her shaky and ever-changing alibi.

The Inquest

During the following hours and days, Lizzie’s rendition of the facts changed so many times that not only the police, but also her lawyers and the public at large were left to wonder if any of her statements were true. After the police determined there was no possibility a murderer could have escaped the house undetected, a logistical impossibility according to the many witnesses out and about on the street that morning, Lizzie was ultimately considered the lone suspect and placed under arrest. The Fall River Police Department Arrest Log Book for 1892 shows that Lizzie was booked and charged with "murder of father."

At first, Lizzie’s account of the facts as she remembered them were clear, but as she continued, she kept remembering this or forgetting that. Surprisingly enough, none of those questioning her seemed willing to press her about the contradictions. If one is curious enough to wade through the hundreds of pages of inquest and trial testimony in the hopes of finding something in common with all her statements, one does so in vain. It seems as if Lizzie contradicted each and every statement she ever made, from the moment she claimed she found her father, to that particular moment in court. Again, oddly enough, both prosecuting and defense attorneys seemed hesitant to press her, with the exception of one occasion, to try to clarify her many different statements:

Q. Where were you when your father came home?

A. I was down in the kitchen. Reading an old magazine that had been left in the cupboard, an old Harper’s Magazine.

Mere seconds later, District Attorney Knowlton asked if she was sure.

A. I am not sure whether I was there or in the dining room

Still minutes later the question was asked again.

Q. Where were you when the bell rang?

A. I think in my room up stairs.

Q. Then you were up stairs when your father came home?

A. I was on the stairs when she (Bridget) let him (Andrew) in ... I had only been upstairs long enough to take the clothes up and baste the little loop on the sleeve. I don’t think I had been up there over five minutes.

Minutes later and obviously growing frustrated with the witness, the D.A. asked;

Q. …you remember that you told me several times that you were downstairs and not up stairs, when your father came home? You have forgotten, perhaps?

A. I don’t know what I have said. I have answered so many questions and I am so confused I don’t know one thing from another. I am telling you just as nearly as I know.

The D.A. tried once again to get the facts.

Q. …Which now is your recollection of the true statement, of the matter, that you were down stairs when the bell rang and your father came in?

A. I think I was down stairs in the kitchen.

Q. And then you were not upstairs?

A. I think I was not because I went up almost immediately, as soon as I went down, and then came down again and stayed down.

(To read the entire transcript of the testimony, see the Fall River Police Dept. files at http://www.frpd.org)

And so it went. While awaiting trial, Lizzie spent nine months in the Taunton Jail, though it was hardly a stint of hardship for her with such amenities as daily strolls and catered hotel food for her meals.

The Trial

Lizzie Borden’s trial began on Monday, June 5, 1893 in New Bedford, the county seat of Bristol County, 15 miles from Fall River. She was indicted on three counts: the murder of Andrew Jackson Borden, the murder of Abby Durfee Borden, and the murder of Andrew and Abby Borden.

Two prosecutors presented the bulk of the state’s case, D. A. Hosea Knowlton and his new assistant, William H. Moody, for whom this was his first trial. Their presentation focused on three major points: a burned dress, a hatchet with a missing handle, and Lizzie’s whereabouts at the time of the crime.

The prosecution, according to Edward Radin’s Lizzie Borden: The Untold Story, got off to a bad start when the inexperienced Moody called Thomas Kieran, an engineer, as its first witness. The state had retained Kieran to take precise measurements and drawn the floor plan of both the downstairs and upstairs rooms on the Borden house. With Kieran on the stand, Moody opened the second day of trial by stating: "The prisoner (Lizzie Borden) from the hall above made some laugh or exclamation. At that time, gentlemen, Mrs. Borden’s body lay within plain view of that hall" and Lizzie must have been able to see it as she climbed the stairs. Kieran did not concur. He testified that he had had his partner lay down on the floor in an approximate location where Abby Borden’s body had been found and that he could only see the body from one particular spot on the stairs, and only if he looked carefully.

Another blow followed when another prosecution witness, Dr. Seabury Bowen, the Borden family doctor, testified that he had given Lizzie doses of morphine after the murders, during her initial hearing, and throughout her stay at the jail. The defense immediately pounced upon that bit of news and protested that the effects of such medication, though given to calm her nerves, could have perceptibly altered Lizzie’s recollections and view of things, thus accounting for her often contradictory statements.

The state’s first productive witness was Alice Russell, a neighbor and good friend of Emma Borden. Frank Spiering in Lizzie recounts that Russell testified that the night before the murders, Lizzie came to her and told her she felt "afraid sometimes that Father has got an enemy" and that somebody "will do something." Spiering also reported that Russell testified at the Grand Jury hearing that on the Sunday following the murders (the murders occurred on the previous Thursday) that she, Emma and Lizzie were in the kitchen. Lizzie stood near the cupboard door and stove, either ripping something or tearing apart a dress – a cheap cotton calico dress of light blue background with dark figures. The dress that Lizzie had provided the police as the dress she wore the morning of the murders was a heavy winter bengaline silk dress of a navy blue background with light blue figures. (The police had asked Lizzie to provide them the clothing she had on when the police arrived the morning of the murder and she promptly did so, but neither the police nor the prosecution later apparently gave any thought to the possibility that she might have changed her clothes before the police arrived. Nor did she supply them with the socks or shoes she wore that morning, but later supplied them with a pair of black strap slippers and a pair of black stockings, which she admitted she had washed.)

The prosecution’s rout of itself resumed in full view of the jury when the prosecution introduced the axe head from the alleged murder weapon. The prosecution attempted to show that the axe head found in the box with the other two had been disguised with ashes to blend in with the others and that its missing handle had left freshly sheared bits of wood protruding from the axe head. The prosecution postulated that the fact that the handle was missing seemed to point to someone within the house not only having had access to it, but to destroy it as well. As intriguing as this speculation may have sounded to the jury, it didn’t get to dangle long before a prosecution witness would knock it down. When Dr. Edward Wood of Harvard Medical School was called to testify regarding the forensic findings from the hatchet head, he said all the stains on the hatchet had been tested by chemical and microscopic methods with negative results. No blood. He also stated that he had removed a portion of the wood from the broken handle in the eye of the hatchet and tested it with iodine of potassium, which removes blood pigment. Again, no traces of blood were found. He did state that while blood could have been washed off with cold water, it would have had to been done thoroughly and deeply.

Police officers testified. Fall River rookie Medley inspected the barn loft where Lizzie claimed she had been at the time of the murders, but testified he found no evidence of anyone having been in the loft – dust lay thick over everything and the solitary window locked. Sgt. Harrington testified that he saw the remains of what looked like rolled papers in the stove.

The prosecutions strongest point hinged on Lizzie’s own conflicting testimony, which D.A. Knowlton intended to show by calling to the stand Annie White, the stenographer who had recorded the proceedings of Lizzie’s initial statements to the police, statements riddled with inconsistencies.

The defense immediately countered Knowlton’s efforts by claiming Lizzie’s testimony was inadmissible for the following reasons:

* Prior to the inquest, Lizzie had been under constant surveillance and had already been informed that she was a suspect.

* Lizzie’s request to be represented by counsel had been refused by the district attorney and the judge.

* After giving her testimony, Lizzie wasn’t allowed to leave and within two hours was placed under arrest.

* A warrant had been issued before the inquest but was not served – Lizzie wasn’t told about the first warrant.

The court ruled in favor of the defense, saying that Lizzie had been under virtual arrest at the time of her questioning and that as such her inquest testimony was to be excluded from the proceedings. It was the worst possible ruling for the prosecution, as they were now unable to show the radical swings in Lizzie’s testimony.

The Defense

Andrew Jennings, who for years had been Andrew Borden’s attorney, was convinced from the outset that Lizzie was incapable of axing her father and stepmother to death, and he quickly took up her case, agreeing to defend her. George Robinson joined him in presenting Lizzie’s defense at trial. The defense presentation took only a day and a half. It set out promptly to destroy any credibility of the prosecution’s case, knowing that only two lingering points could still put Lizzie in danger: her hatred of Abby and the burning of her blue dress. The plan was to prove that not only was the prosecution’s case against Lizzie circumstantial, but totally unfounded.

The defense called a number of witnesses who had reported seeing various men in the immediate area of the Borden home on the morning of the murders. One witness said he saw a man delivering ice in the neighborhood, another witness said he noticed a man standing outside the Borden house on the sidewalk for a while, but as he never strayed from the sidewalk, his presence did not make much of an impression. The testimony of these witnesses was essentially conflicting but it did raise the possibility of an intruder in the neighborhood that day.

The defense pointed out that the prosecution could not produce the murder weapon. What had happened to it? If Lizzie had never left the house, where could the handle have disappeared? Such supposition cast further doubt in the minds of the jury. Unfortunately, Dr. Wood, upon cross-examination, did nothing to help the prosecution when he replied to a question about the lack of blood splatter. He said he was sure the culprit would have been covered in blood.

Lizzie’s friend Marianna Holmes testified regarding Lizzie’s religious activities, stating Lizzie was a Sunday school teacher for Chinese children, deepening the jury’s impression that a staunch Christian woman of Lizzie’s sensitivities could never have wielded a hatchet to do more than chop a piece of kindling.

Phoebe Bowen, Dr. Bowen’s wife, testified that she had been with Lizzie shortly after the murders were discovered and that Lizzie had been pale and faint. She had seen no blood on Lizzie.

The defense also had Bridget Sullivan’s testimony read, stating that Lizzie was agitated and in tears when the bodies were discovered.

But the defense witness that everyone waited with bated breath to hear was presented on the 11th day of the trial. Emma Borden finally appeared, dressed in a black dress, black gloves and black patent leather shoes.

Andrew Jennings spoke gently to the older sister, a small bird-like woman with frightened dark brown eyes. To begin, the questioning seemed simple and straightforward, almost boring until the topic of Lizzie’s burned blue dress was brought up. Even then, the questions and answers seemed rehearsed, as if it had been agreed upon ahead of time what the two would discuss on the stand. When asked about the dress, Emma said she had told Lizzie, "You have not destroyed that old dress yet. Why don’t you?"

Emma testified that she was in the kitchen with her friend Alice Russell on the Sunday morning following the murder when she turned around and saw her sister standing by the stove, the dress hanging from her arm. Emma quoted Lizzie as saying, "I think I shall burn this old dress." Emma testified that her reply was: "Why don’t you", or "You had better", or "I would if I were you". Emma couldn’t seem to remember which it was. She also claimed that she did not hear Russell say to Lizzie, "I wouldn’t let anybody see me do that, Lizzie".

On the key matter of Lizzie’s relationship to her stepmother, Emma testified that relations between Lizzie and Abby were cordial. During his cross-examination, Knowlton pressed Emma on this point, trying to show the jury the thinness of Emma’s claim. Knowlton asked Emma when Lizzie ceased calling Abby "Mother." Emma said she could not remember. Knowlton persisted with this question in various forms, asking her 12 separate times. To each version of the question, Emma responded: "I don’t remember."

Lizzie was not called to testify. When the judge asked her if she had anything to say to the jury, she stood to say, "I am innocent. I leave it to my counsel to speak for me."

In summation, the defense told the jury, "It is not your business to unravel the mystery… you are not here to find out the murderer…you are simply and solely here to say, is this woman defendant guilty."

In his closing argument, D. A. Knowlton focused once again on the gruesome facts of the crime, reiterating that no one else could have had either the opportunity or the motive to kill the Bordens.

Common perception at the time was that while it could be considered "acceptable" for a woman to commit murder by poison, the possibility of such a delicate creature hacking two people to death with an axe was unthinkable. On Tuesday, June 20, 1893, after only an hour of deliberation, the all-male jury found Lizzie Borden not guilty in the murders of Andrew and Abby Borden.

Aftermath

During the 13 days of testimony that led to Lizzie Borden’s acquittal, the key players had their names splashed in nearly every national newspaper. After the trial, five of them remained in the public eye. Though he failed in his endeavor to convict Lizzie, Knowlton became attorney general of the State of Massachusetts. Andrew Jennings became the district attorney of Bristol County. The Borden sisters also rewarded him for his ardent defense of Lizzie by naming him to the board of directors of the Globe Yarn Mill, one of Andrew Borden’s companies. William Moody gained fame when in 1904 President Theodore Roosevelt appointed him attorney general of the United States.

Lizzie was acquitted in the courtroom but not in Fall River. In the very town where she sought acceptance, she was ostracized. Twenty-nine days after the death of Andrew and Abby Borden, Emma received possession of the Borden estate. Five weeks after Lizzie’s acquittal, the two sisters moved up onto The Hill into a 13-room Victorian house that Lizzie subsequently christened Maplecroft. Seven months after her acquittal, Emma gave Lizzie her share of the inheritance, for all the good it did. Maplecroft became Lizzie’s prison and refuge. Over the years the sisters were relegated more and more to their own company, as no one really wanted to befriend Lizzie.

In 1897, a warrant was issued for Lizzie, regarding a theft of two paintings from a local gallery. She was told that if she signed a confession, the warrant would not be served, but she stubbornly held her ground and refused to sign until the last possible second. While Emma grew more introverted, Lizzie traveled. It was in Boston that she met and greatly admired Nance O’Neil, a Boston actress. Such a profession was still considered unacceptable to most women’s sense of morality at that time, and so when Lizzie gave a lavish party for Miss O’Neal at Maplecroft, Emma became so offended that a rift developed between the two sisters. Emma moved out of the house and relocated to New Hampshire, where she lived without speaking to Lizzie for the next 22 years.

In 1926, Lizzie was admitted to the hospital for a gall bladder operation. Three months later she returned to Maplecroft, but she never regained her health. The following year, at the age of 67, she died. Ten days later, her sister died as well. Both are buried together in the family cemetery beside the bodies of Abby, Andrew and Andrew’s first wife, Sarah.

Forty Whacks

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,757415,00.html

Lizzie Borden took an ax

And gave her mother forty whacks;

When she saw what she had done

She gave her father forty-one!

It was a sweltering August morning in Fall River, Mass. Some of the Borden household felt distinctly under the weather. Night before last both Mr. & Mrs. Borden had been violently sick; this morning Bridget, the maid-of-all-work, felt none too well. But they all got up as usual, went about their daily tasks. After breakfast 70-year-old Mr. Borden walked down town to do some business errands. Bridget, her first chores done, went up to her room to lie down. Mrs. Borden, 64 and fat, puffed up the front stairs to change the pillow slips in the spare room. That left only Stepdaughter Lizzie, a spinster of 32, unaccounted for.

Old Mr. Borden came back from his errands worn out by the heat. He went into the sitting room, stretched out on the sofa. Soon Bridget, dozing in her room, was roused by a cry from Miss Lizzie: ''Come down here! Father's dead; someone came in and killed him!" Mr. Borden was still lying on the sofa, his face and head a mask of blood. He had been hacked to death with some sharp, heavy instrument. His body was still warm, the blood was still flowing. Neighbors came running, the house was searched; in the spare room they found the body of Mrs. Borden lying on the floor, hacked to death in the same manner. She had apparently been killed an hour or so earlier.

That was Aug. 4, 1802. A week later, following the inquest, Lizzie Borden was indicted for the murder of her father and stepmother. It was known that the Bordens were not a happy family. Lizzie and her older sister (who was visiting friends at the time of the murders) resented their stepmother, kept to themselves as much as possible in the front of the house. By Fall River standards of those days, Mr. Borden was a rich man. Two days before the inquest, Lizzie burned up a dress. Her testimony at the inquest—she was never put on the stand during her trial—was contradictory on some points, evasive on others. Nevertheless, since there was only circumstantial evidence against her, she was acquitted. The trial (1893) was a national sensation, even eclipsing the Chicago World's Fair. Many a newspaper reader thought Lizzie innocent, but the majority in Fall River thought otherwise. One of the many current jokes about the case: on Aug. 4 somebody asked Miss Lizzie the time of day. Said she: "I don't know, but I'll go and ax Father."

For years afterwards the Fall River Globe kept the bloody memory of Aug. 4 alive, every year on that date ran a thinly veiled attack on Lizzie Borden. Fall River citizens shunned her on the street. She changed her name to Lizbeth, but refused to move away. Did Sister Emma suspect her? No one knows. They lived together for eleven years, then Emma left her, never saw Lizzie again. When they died, in the same year (1927), they were buried in the Fall River cemetery alongside the others.

Last week Edmund Pearson, who specializes in writing up famed U. S. murder cases, published a full-length dissection of the Lizzie Borden mystery, complete with photographs of the victims, plans of the house, rescript of the trial and inquest testimony. Author Pearson was careful not to bring in a verdict, or at least not to say it out loud; but he obviously thought Lizzie Borden was lucky, not innocent.

Lizzie Borden House Tour

Crime Scenes Make Killing With Tourists

Americans Love to Follow in Felonious Footsteps

http://abcnews.go.com/Entertainment/WolfFiles/story?id=979701&page=1

Give yourself 40 whacks if you forgot to wish Lizzie Borden a happy birthday. America's most famous axe murderess would have been 145 this week. And though she's no longer with us, you can still sleep in her bed -- as long as you make reservations.

The Lizzie Borden Bed and Breakfast in Fall River, Mass. -- the very spot where Andrew and Abby Borden were hacked to death -- has been restored to its 1892 splendor, when the abode earned its infamy. As the twisted nursery rhyme goes:

"Lizzie Borden took an Axe,

And gave her mother forty whacks,

When she had seen what she had done,

She gave her father forty-one."

Borden was eventually acquitted, and now, a night in her room is $200. Or if you want, you and your friends can rent the entire seven-bedroom house for $1,160. One couple is even planning to marry there later this year. On Halloween, of course.

Too creepy? If you'd rather, the house offers daily tours, where you can pick up $5 hatchet-shaped silver earrings, gift books, T-shirts ("Axe Me Where I Live … ), or a $10 vial of basement dust, which comes with a letter of authenticity.

"It's a little piece of history, a mystery that people can still share in," says co-owner Lee-ann Wilber, who purchased the premises two years ago.

All over the country, yesteryear's crime scenes are today's tourist destinations. Go to Jesse James' farm in Kearney, Mo., and see the bullet hole in the wall from when the famed gunslinger was killed.

James was standing on a chair and straightening a picture, when a member of his own outlaw gang shot him in the back in hopes of collecting a $10,000 reward. The bullet is under Plexiglas and on display, along with a casting of James' skull.

At the Dalton Gang hideout in Meade, Kan., you can creep into the 95-foot-long escape tunnel that runs under the 19th-century abode. More action awaits at Ma Barker's place over in Oklawaha, Fla., where they annually re-enact the Jan. 16, 1935, gunfight, when police riddled the home with 3,500 rounds of ammunition.

Then, try relaxing at Al Capone's Hideout in Couderay, Wis., a fortified lakeside estate with bulletproof walls, gun turrets and a guard tower. It's now a restaurant and bar.

Just don't confuse it with the mob boss's other makeshift museums, including a onetime Chicago speakeasy that's now "Al Capone's Hideaway & Steakhouse." Among other historical items, a sign in the men's room says, "Big Al Was Here."

It's no wonder contemporary crime scenes fetch big bucks. Three weeks ago, the Modesto, Calif., bungalow once occupied by convicted double murderer Scott Peterson and his slain pregnant wife, Laci, sold for $390,000 -- $10,000 more than Laci's parents were asking for the place.

"It's probably the most controversial home in the world," the buyer, Realtor Gerry Roberts, told The Associated Press. Roberts says, however, he plans to live there with his wife and three children.

A week later, a bidding war broke out over the home of BTK killer Dennis Rader, who admitted to killing 10 people in Wichita, Kan., between 1974 and 1991.

One bidder, Byron Jones, offering $60,000 for the home -- $3,000 more than its assessed value -- says he was planning to sell the abode, "inch by inch," over the Internet.

Exotic dance club owner Michelle Borin finally plunked down $90,000, saying she has no plans to live in the place. She just wanted the proceeds to help Rader's family. A court, however, may hold up the sale as victims of the killer press a wrongful death suit.

"It's just hideous to allow people to profit from crime," says Polly Franks, a spokeswoman for the National Coalition of Victims in Action. "Think of what this means to the people who suffered."

People often feel compelled to visit tragic locations, a motivation that might go back as far the very first battlefield monument. But you can't say crowds go to Capone's hideout or Borden's place to pay their respects.

"It's really a matter of time and taste before something like this becomes acceptable," says Chris Epting, author of "Elvis Presley Passed Here," the latest in his series of pop cultural landmarks.

Perhaps only in America can an outlaw like Jesse James rob a railroad in 1873, and then, 81 years later, get the railroad to erect a monument to commemorate this evil deed. And you'll find such a monument in Adair, Iowa, where his crew committed one of the first train robberies of the Old West, hauling off $2,000.

Borden was the bane of Fall River, but long after everyone directly related to the case had passed away, the quaint Massachusetts hamlet accepted -- in some respects even embraced -- its spot in history.

Here are some other crime scenes that have become magnets for tourists:

1. Bonnie and Clyde's Latest Hit

How's this for a quick getaway? On the third weekend of May, some 5,000 Bonnie and Clyde aficionados make an annual pilgrimage to Gibsland, La., to witness the re-enactment of the fateful 1934 shootout that marked the bloody end for the Romeo and Juliet of armed robbery.

The couple's two-year crime spree had left at least 12 people dead. They had stopped on Route 154 to help a farmer with a flat tire when they were ambushed by six officers.

Bonnie and Clyde made headlines in their day, but festival coordinator Billie Gene Poland says they would have been forgotten footnotes in true crime magazines if not for the 1967 blockbuster movie, starring Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway.

"People just started coming here, asking questions. Finally, someone said, 'You're sitting on a goldmine,'" Poland says.

"We aren't doing this to glorify crime. We aim to honor the law enforcement officers and to teach people about the real history."

Criminal historians and relatives of both Bonnie and Clyde and also the officers who pursued them have participated in festival forums and attended the roadside shootout show. The extravaganza features actors from Denton, Texas, where the lawless lovebirds twice robbed the local bank.

Each year, the actors roll out the same vintage Bonnie and Clyde car that was used in the movie, and every year it's shot up like Swiss cheese. The real getaway car was purchased for $85,000 and is on display at Whiskey Pete's Casino, just outside Las Vegas.

Just to indicate the enduring popularity of the couple, candles and love notes are regularly found left at the couple's graves in Dallas. They're buried 10 miles apart, however, because Bonnie Parker's mother disapproved of the relationship and would not stand to see them side by side for eternity.

2. Alferd Packer's Flesh-Eating Festival

You could say Alferd Packer -- the first American tried on charges of cannibalism -- got his just desserts. In 1874, he was convicted of throwing a dinner party in really bad taste. Nowadays, he suffers an afterlife of totally tasteless jokes.

In the rugged winter of 1873, Packer was trapped in Colorado's San Juan Mountains along with five other prospectors. He emerged 65 days later looking suspiciously plump.

Packer never denied that he ate his colleagues. He claimed that he killed only one victim, and that was in self-defense.

As legend has it, at the sentencing, the presiding judge told Packer, "There were nine Democrats in Hinsdale County, and you ate five of them," and sent him off to die.

But Packer escaped the hangman's noose through a technicality. He was tried again, convicted, and served 40 years. But he proclaimed his innocence to the very end.

Now, in Lake City, Colo., where America convicted its first cannibal, they celebrate Alferd Packer Days -- a two-day celebration, with coffin races, bone-throwing contests, and excursions to Dead Men's Gulch, where Packer's victims were exhumed. The next gala will be held on Memorial Day.

In nearby Littleton, where Packer was buried, the local museum in past years has hosted a re-creation of the prospector's criminal trial, topped off with a "Beef Alferdo" memorial dinner.

Cannibal jokes have become especially popular at the University of Colorado at Boulder. After a 1968 student protest over lousy on-campus grub, students voted to rename a cafeteria the Alferd Packer Grill. They subsequently began celebrating their own Alferd Packer Day with a speed-eating contest featuring barbecued ribs and steak tartar.

Two of the university's most famous students, "South Park" creators Matt Stone and Trey Parker, based their first collaboration, the 1996 feature film "Cannibal: A Musical," on Packer's life. The movie poster promised, "All Singing! All Dancing! All Flesh Eating!"

3 'Wild Bill' Hickok Lives On

These days in Deadwood, S.D., "Wild Bill" Hickok gets himself killed four times a day, seven days a week, and that doesn't include a few staged gunfights in the streets. It's the only way to keep a gold rush of tourists happy.

Casino gambling brought a big boost in the early 1990s, and the HBO series that chronicles the outlaw legends born here, has given this Black Hills frontier town major international exposure, with tourists flocking here to walk the same streets as Calamity Jane.

As legend has it, on Aug. 2, 1876, Hickok was playing poker at the Old Style Saloon No. 10, and gave the world a lesson on why you should never sit with your back to the door. A shifty drifter named Jack McCall wandered in, just as Hickok drew what's now known as a "Dead Man's Hand" -- a pair of black aces, a pair of black eights and a nine of diamonds.

Hickok was shot in the head, and he's buried on nearby Mount Moriah, where many people come to show their respects. Some couples have even married there dressed in 1800s Western garb.

"I think Hickok was a good man, given the time and place he lived," says Marcus Vilimos, an actor who plays Hickok at the Old Style's daily shows.

"In those days, you had to do some unconventional things to do what was honorable. That's what people are attracted to. This place is rich with stories."

If you decide to test your luck at the Old Style, it's your lucky day if you draw the infamous Dead Man's Hand. The casino pays out a $250 prize.

Losers can still take home a $7 souvenir saloon thong. Just don't give it to a stranger if your back is to the door.

American Justice: Lizzie Borden

Arnold Brown's Theory of the Lizzie Borden Case

Legend of Lizzie Borden

James Starrs on Lizzie Borden Graves, 1992

![Brotherhood" (2006) [TV-Series]](http://photos1.blogger.com/x/blogger2/1421/379621144723082/211/z/425926/gse_multipart33129.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment