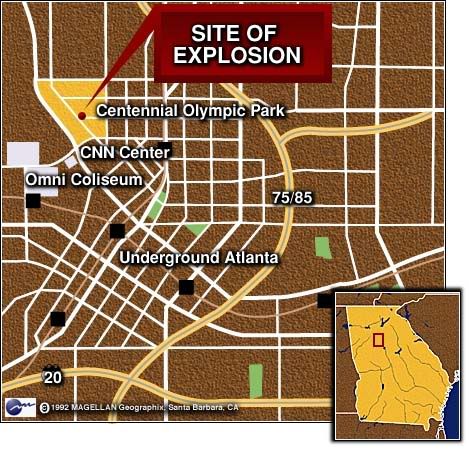

The Centennial Olympic Park bombing was a terrorist bombing on July 27, 1996 in Atlanta, Georgia during the 1996 Summer Olympics, the first of four committed by Eric Robert Rudolph. Two people died, and 111 were injured.

Bombing

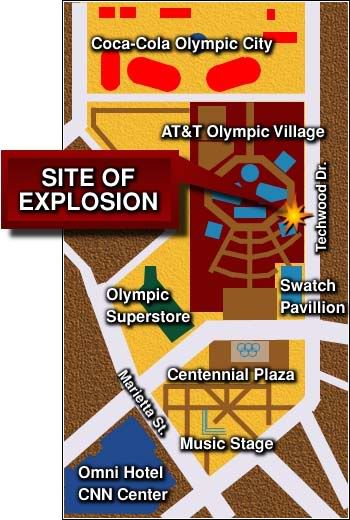

Centennial Olympic Park was designed as the "town square" of the Olympics, and thousands of spectators had gathered for a late concert by the band Jack Mack and the Heart Attack. Sometime after midnight, Rudolph planted a green military ALICE pack (knapsack) containing three pipe bombs surrounded by nails underneath a bench near the base of a concert sound tower. He then left the area. The pack had a directed charge and could have done more damage but it was tipped over at some point.

Security guard Richard Jewell discovered the bag and alerted Georgia Bureau of Investigation officers; 9 minutes later, Rudolph called 911 to deliver a warning. Jewell and other security guards began clearing the immediate area so that a bomb squad could investigate the suspicious package. At 1:21am, the bomb exploded.

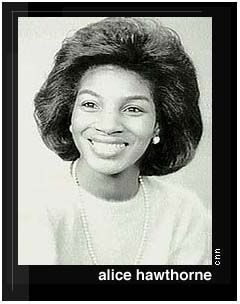

A Georgia woman, Alice Hawthorne, was killed by a nail that struck her in the head. The bomb wounded 111 others. Turkish cameraman Melih Uzunyol died from a heart attack he suffered while running to cover the blast.

Reaction

President Bill Clinton denounced the explosion as an "evil act of terror" and vowed to do everything possible to track down and punish those responsible. At the White House, Clinton said, "We will spare no effort to find out who was responsible for this murderous act. We will track them down. We will bring them to justice."

Despite the tragedy, officials and athletes agreed that the "Olympic spirit" should prevail and that the games should continue as planned. The crash of TWA Flight 800 off Long Island, which had occurred just 10 days earlier on July 17, 1996, was likewise not considered a reason to postpone the games.[2]

Richard Jewell falsely implicated

Though Richard Jewell was hailed as a hero for his role in discovering the bomb and moving spectators to safety, four days after the bombing, news organizations reported that Jewell was considered a potential suspect in the bombing. Rudolph, at the time, was unknown to authorities, and a lone bomber profile made sense to FBI investigators. Though he was never arrested or named as more than a "person of interest", Jewell's home, where he lived with his mother, was searched and his background exhaustively investigated, all amid a media storm that had cameras following him to the grocery store.

Jewell was cleared of suspicion by the United States Department of Justice in October of 1996, and Attorney General Janet Reno publicly apologized later, but he claimed that the negative media attention had ruined his reputation. He eventually settled libel lawsuits against a former employer, Piedmont College in Northern Georgia, as well as CNN, ABC, and NBC. A lawsuit is still pending against the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, which was the first news organization to report that he had been labeled a suspect. [1]

Jewell worked as a police officer in Pendergrass, Georgia. On August 29, 2007, he was found dead in his home, his death apparently a result of natural causes

Eric Robert Rudolph

After Jewell was cleared, the FBI admitted it had no other suspects, and the investigation made little progress until early 1997, when two more bombings took place at an abortion clinic and a lesbian nightclub, both in the Atlanta area. Similarities in the bomb design forced investigators to concede that a terrorist was on the loose. Letters sent to newspapers claiming responsibility in the name of the Army of God focused attention on the problem of right-wing extremism.[citation needed] One more bombing of an abortion clinic, this time in Birmingham, Alabama, which killed a policeman working as a security guard and seriously injured nurse Emily Lyons, gave the FBI crucial clues including a partial license plate.

The plate and other clues led the FBI to identify Eric Robert Rudolph as a suspect. Rudolph eluded capture and became a fugitive; officials believed he had disappeared into the rugged southern Appalachian Mountains, familiar from his youth. On May 5, 1998, the FBI named him as one of its ten most wanted fugitives and offered a $1,000,000 reward for information leading directly to his arrest. On October 14, 1998, the Department of Justice formally named Rudolph as its suspect in all four bombings.

By 1999, on the third anniversary of the bombing, Rudolph had not been seen for over a year, and authorities sometimes voiced a belief or hope that Rudolph had succumbed to the elements. After more than five years on the run, Rudolph was arrested on May 31, 2003, in Murphy, North Carolina. On April 8, 2005, the government announced Rudolph would plead guilty to all four bombings, including the Centennial Olympic Park attack, in a deal to avoid the death penalty.[citation needed]

Rudolph's justification for the bombings according to his April 13, 2005 statement, was political:

In the summer of 1996, the world converged upon Atlanta for the Olympic Games. Under the protection and auspices of the regime in Washington millions of people came to celebrate the ideals of global socialism. Multinational corporations spent billions of dollars, and Washington organized an army of security to protect these best of all games. Even though the conception and purpose of the so-called Olympic movement is to promote the values of global socialism, as perfectly expressed in the song Imagine by John Lennon, which was the theme of the 1996 Games even though the purpose of the Olympics is to promote these despicable ideals, the purpose of the attack on July 27 was to confound, anger and embarrass the Washington government in the eyes of the world for its abominable sanctioning of abortion on demand.

The plan was to force the cancellation of the Games, or at least create a state of insecurity to empty the streets around the venues and thereby eat into the vast amounts of money invested.

On August 22, 2005, Rudolph, who had previously received a life sentence for the Alabama bombing, was sentenced to three concurrent terms of life imprisonment without parole for the Georgia incidents. Rudolph read a statement at his sentencing in which he apologized to the victims and families only of the Centennial Park bombing, reiterating that he was angry at the government and hoped the Olympics would be cancelled. At his sentencing, fourteen other victims or relatives gave statements, including the widower of Alice Hawthorne.

Rudolph is currently incarcerated in the supermax federal prison in Florence, Colorado, ADX Florence, which also houses Ted Kaczynski (the Unabomber), Terry Nichols (of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing), Ramzi Yousef (of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing), and Zacarias Moussaoui (professed al-Qaeda member convicted of conspiracy to commit murder for the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon).

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Centennial_Olympic_Park_bombing

Olympic Park bombing - July 1996

http://www.cnn.com/US/9607/27/olympic.bomb.main/index.html

Bomb Rocks Atlanta Olympics

http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=M1ARTM0010968

It was shaping up as a picture-perfect end to an otherwise decidedly imperfect start for Atlanta's troubled 1996 version of the Olympic Summer Games. After a week filled with gripes about everything from American jingoism to inflated prices to endless traffic and technology foul-ups, the city was finally living up to its fabled reputation for Southern hospitality last Friday night. The day's athletic events went smoothly, the logistics were relatively glitch-free and well after midnight, tens of thousands of revellers were still gathered in Centennial Olympic Park, listening to an open-air concert by Jack Mack and the Heart Attack. Then, shortly after 1 a.m. on Saturday, a telephone operator picked up an emergency 911 call from a man who, an FBI agent said later, "made a specific threat" about a bomb in the park. Eighteen minutes later, the bomb went off in front of a four-storey-high tower where technicians controlled the sound and lighting near the stage. It exploded with a bright blue flash and an impact that shook an area of three city blocks, blowing out windows within 100 m. The blast caused one death directly, resulted in an additional fatal heart attack, and left more than 100 other people injured.

In that instant, an event that is supposed to celebrate the fellowship of the international athletic community was tragically transformed into a far more deadly contest, with life-and-death stakes. As Canadian rower Silken Laumann said: "It's sad that something that is supposed to be about peace and fair play becomes a target like this." The bombing, and follow-up warnings that proved to be false alarms, cast a pall over the close of the first full week of the 16-day Atlanta Games. And the casualties took some of the shine off a Canadian day of triumph that began with a gold medal and two silvers in rowing races and closed with Donovan Bailey powering his way to victory - in world-record time - over a formidable field in the 100-m dash.

The Atlanta bomb blast caught Americans still reeling from the explosion of a TWA jetliner 10 days earlier that killed 230 people and appeared to be an act of sabotage. And now, they were confronted for a second time by the prospect of death by terrorism. The dead were a 44-year-old American woman killed by the blast, and a Turkish cameraman, 40, who suffered a heart attack while running to film the aftermath of the explosion. Most of the injured - none of whom are believed to be Canadian - were wounded by sheet-metal shrapnel blown out from a point near the tower.

In the immediate aftermath, many people were too stunned to realize the enormity of what had just occurred. "There were a lot of people not knowing what was happening," said Michelle Cameron, an Athlete Services worker with the Canadian team and a gold medallist in synchronized swimming at the 1988 Olympics who was nearby. Then, she said, "the streets were flooded with police and fire trucks." And once again, the world was confronted with a shocking reminder that, no matter what the circumstances or security precautions - including more than 30,000 security personnel - there is no such thing as a completely safe place. Along with the lost lives and broken bodies caused by the blast, there were inevitable questions about whether the Olympics, which originated from the simpler ideals of earlier times with amateur athletes, are still appropriate in an era of professionalism, commercialism - and terrorism. There were also haunting reminders of the 11 Israelis murdered by terrorists at the 1972 Munich Olympic Games - and the sad twist that, earlier in the week, their surviving family members failed in an attempt to get official sanction for a ceremony commemorating their loss.

All of that clouded the efforts of the more than 10,000 athletes competing from 197 countries and territories. For Canadian athletes, the blast came just hours before the beginning of what proved to be their single most productive medal-winning day so far in the Atlanta Games. Their Saturday victories raised their one-week total to eight medals - two golds, three silvers and three bronze.

In the morning at Lake Lanier, north of Atlanta, Kathleen Heddle and Marnie McBean won gold in the double sculls, while Laumann and Derek Porter took silvers in the single-scull races. That night in the Olympic Stadium, Bailey turned in a shattering performance, surging to the finish in 9.84 seconds (1/100th of a second under the world mark). Then he ran on, shouting in triumph, and completed his victory lap waving a Maple Leaf flag handed to him from the audience.

The week had already made medal stars of Canadians Clara Hughes in cycling and Marianne Limpert and Curtis Myden in swimming, and crowned champions from around the world such as Ireland's amazing swimmer Michelle Smith. As the Games continued after the bombing, they did so amid a steady rain in Atlanta, flags lowered to half-mast at all venues. At the same time, already tight security precautions were stepped up to a new level that was to remain in place until the end of the Games - and would be felt by virtually everyone near an Olympic site. At Lake Lanier, the site of the rowing finals, soldiers bearing machine-guns patrolled the grounds, and other soldiers replaced the usual Olympic security personnel at checkpoints. Troops with flashlights scanned under buses carrying media and spectators, and all bags taken to seats and working areas were examined. Even the athletes faced thorough searches.

In the wake of the blast, some security personnel at the Games privately expressed relief that the death and injury toll was not worse. The park where the explosion occurred has been popular as a free-admission gathering place and entertainment centre for events surrounding the Games, featuring a giant beer pavilion, virtual reality rides and concerts by acts including longtime star Kenny Rogers. As well, FBI agents said that there may in fact have been more than one explosive device involved in the blast. There were indications that the bomb held nails and screws, amounting to what FBI spokesman Woody Johnson described as "an anti-personnel fragmentation device, a homemade bomb."

Before the Games began, the chief organizer, Billy Payne, said: "The safest place on this wonderful planet will be Atlanta during the time of our Games." And for Payne, a real estate developer, Centennial Olympic Park was to be one of the principal showcases, a refurbished facility built in the middle of what had been one of the city's most rundown areas. On the day after the blast, the park was closed and desolate, with barriers blocking all the nearby streets.

For both athletes and spectators, everything changed. Outside the Olympic Village, the tension was palpable. Inside, it was hard to imagine how it could become more tense. Even before the bomb, some athletes and organizers had said they could not decide whether their isolation inside the Village was a curse or a relief. In an interview three days earlier, Deryk Snelling, a Canadian swim coach, said: "The scary part is that we're separated from people, and I wish we weren't because these should be the people's games. The parents and everybody who's worked with the kids can't lean over the fence and shake hands without being stopped. But that's life in America - and probably everywhere else, come to think of it." Even at the meeting place of many nationalities on a soft summer night, violence became a part of everyday life.

Bombing victim loved life

http://www.cnn.com/US/9707/olympic.park.bombing/hawthorne/

ATLANTA (CNN) -- The death of Alice Hawthorne cast a pall over the Summer Olympics.

She was the only person to die from the bombing in Centennial Olympic Park, although a Turkish television cameraman died of a heart attack while rushing to videotape the aftermath of the downtown explosion.

To those who knew her, the 44-year-old Hawthorne, an entrepreneur and cable TV customer service and sales representative from Albany, Georgia, represented much of what was good about life -- determination, generosity, spunk.

The mother of two daughters drove to the park in downtown Atlanta after work on July 26 as a birthday present to her 14-year-old, Fallon Stubbs. The two were dancing at an outdoor concert by a rhythm-and-blues band when the pipe bomb exploded early the next morning.

"If somebody went to all the trouble to bring the Olympics to Atlanta, the least I can do is go," the outgoing Hawthorne was quoted as telling friends before the trip.

Deadly shrapnel pelted Hawthorne and injured Fallon and 110 other people. A doctor and nurse tried to revive Hawthorne at the scene, but she was pronounced dead on arrival at a hospital. Fallon was hospitalized briefly.

Hawthorne, a Georgia native, grew up in the Atlanta suburb of Douglasville. Her parents divorced, and her mother, a cleaning woman, encouraged her children's aspirations.

After graduating from high school, Hawthorne moved to Albany to attend Albany State College (now University), where she earned her marketing degree -- despite several interruptions -- in 1994. She served in the Army and Air Force.

Fallon was the daughter of Hawthorne's first husband, John Stubbs; an older daughter, Adoria Minor, was from another relationship. Hawthorne and Stubbs divorced in 1984, and she married John Hawthorne Jr. in 1987.

Hawthorne worked at TCI of Georgia. In 1993, she opened Fallon's Hot Dog & Ice Cream Parlor, fulfilling her longtime dream of owning a business. It was named after her daughter.

Hawthorne's willingness to cheerfully help others was one of her striking qualities, those who knew her said.

She volunteered at Fallon's school, the Albany Area Chamber of Commerce and the American Legion Post 512. Ironically, as a goodwill ambassador for the Chamber, one of her last civic contributions was to organize and publicize the running of the Olympic torch through Albany.

Georgia Gov. Zell Miller and Andrew Young, co-chairman of the Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games, attended the memorial service held for her in Albany. The Olympic flag was flown at half-staff, and world leaders offered condolences.

Eric Robert Rudolph (born September 19, 1966), also known as the Olympic Park Bomber, is an American anti-abortion and anti-gay extremist and domestic terrorist,[2][3] who committed a series of bombings across the southern United States, which killed three people and injured at least 150 others. He declared that his bombings were part of a guerrilla campaign against abortion, what he describes as "the homosexual agenda," and perceived support for it from the United States government. He spent years as the FBI's most wanted criminal fugitive, but was eventually caught. In 2005 Rudolph pled guilty to numerous federal and state homicide charges and accepted five consecutive life sentences in exchange for avoiding a trial and the death penalty. Rudolph was "connected with the Christian Identity movement, a militant, racist, and anti-Semitic organization" today, he self-identifies as a Catholic.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eric_Robert_Rudolph

Atlanta Olympic bombing suspect arrested

Victim: 'That's the ultimate goal, to see him in court'

http://www.cnn.com/2003/US/05/31/rudolph.main/index.html?iref=newssearch

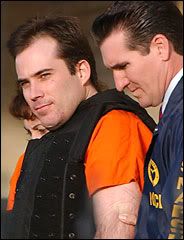

MURPHY, North Carolina (CNN) -- Olympic bombing suspect Eric Robert Rudolph -- wanted in attacks that killed two people and injured more than 100 in the Southeast -- was arrested early Saturday in western North Carolina and faces a Monday morning court date.

Rudolph has been charged in the 1996 Centennial Olympic Park bombing in Atlanta, Georgia; 1997 bombings at a gay nightclub and a clinic that performed abortions in the Atlanta area; and a bombing at a clinic in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1998.

If convicted, he could face the death penalty. The decision would be up to U.S. Attorney General John Ashcroft.

Saturday night, he was in the Cherokee County Jail, having eaten, slept, and talked to investigators, said Chris Swecker, the FBI special agent in charge. Officials said he will appear in court at 10 a.m. Monday in Asheville, North Carolina.

Murphy police Officer Jeffrey Scott Postell, who joined the department on his 21st birthday in July, told reporters that he spotted Rudolph at about 4 a.m. behind a Save-a-Lot grocery store during a routine patrol. He said he thought he'd come across a possible burglary in progress.

"As I came around the corner, I turned my headlights off," Postell said, "and I observed a male subject squatted in the middle of the road. As I approached, he took off running and hid behind some milk crates.

"Not knowing who it was or what he had, I took safety into concern and advised him to come out, and he complied with everything I asked him to do," he said.

Postell called for backup and was assisted by Cherokee County sheriff's deputies.

Deputy Sean Mathews assisted with the arrest.

"I thought he had an uncanny resemblance to Eric Robert Rudolph," Mathews said. "I just had a hunch when I seen his eyes."

Rudolph had sparked a multimillion-dollar manhunt involving hundreds of law enforcement officers in the 500,000-acre Nantahala National Forest area surrounding Murphy and nearby Andrews. (Full story)

"It was just in a day's work," Postell told reporters. "I don't really deserve any credit. I was just doing what I was supposed to be doing."

Rudolph, now 36, had eluded law officers for five years. (Full story)

The last known sighting of Rudolph was in July 1998, when he tried to buy food and other supplies from health food store owner George Nordmann. Nordmann told authorities that he decided not to help Rudolph. Two days later, Nordmann said he came home and found that 75 pounds of food and his truck were missing. Five $100 bills were on his table. Nordmann's truck was found a few days later.

In a statement Saturday, Ashcroft called Rudolph "the most notorious American fugitive on the FBI's 'Most Wanted' list.

"This sends a clear message that we will never cease in our efforts to hunt down all terrorists, foreign or domestic, and stop them from harming the innocent," he said.

Rudolph disappeared after his pickup truck -- first spotted near the scene of the Birmingham attack on January 29, 1998 -- was found abandoned in the North Carolina woods not far from where he was captured Saturday.

The FBI put Rudolph on its "10 Most Wanted Fugitives" list and offered a $1 million reward after the Birmingham attack.

The blast killed off-duty police officer Robert Sanderson, who was working as a security guard at the clinic, and seriously injured nurse Emily Lyons, who was on her way in to work. (Timeline: Events in Rudolph's life)

Lyons, who lost an eye and was permanently disabled, told CNN on Saturday that she always believed Rudolph was alive and hiding in North Carolina, and that she was hopeful that "this was the real thing, this time."

She said she hoped to see Rudolph in court and ask him "Why?"

"What was it that you picked that day, that place, for what purpose?" she said. "Why did you do the Olympics? Why did you do [that] to the others in Atlanta? What were you trying to tell everybody that day?

"That's the ultimate goal, to see him in court, possibly to talk to him and to see the final justice done," she added.

Rudolph is also wanted in connection with the bombing at Centennial Olympic Park in July 1996 in Atlanta, which killed Alice Hawthorne, a 44-year-old Albany, Georgia, woman, and injured more than 100 people. (1997 Special Report: The Olympic Park bombing)

He was also being sought in the double bombing outside a suburban Atlanta women's clinic in January 1997 and another at an Atlanta gay nightclub in February 1997. Several were injured in the incidents, but no one was killed.

Both the women's clinic and nightclub bombings involved secondary bombs designed to go off later than the first, after emergency service personnel had arrived on the scene. Seven people were hurt in the second bomb at the clinic; authorities found the second bomb at the nightclub and disabled it. (Gallery: Rudolph's alleged crimes)

The Southeast Bomb Task Force -- formed to investigate the bombings -- maintained a presence in western North Carolina, at times with as many as 200 federal agents combing a 500,000 acre mountainous and densely wooded area.

Atlanta Olympic bomber apologizes, killed one, injured 100

http://www.cbc.ca/world/story/2005/08/22/Atylanta_Olympic_bomber_apology20050822.html

The man who set the bomb in the public square during the Atlanta Summer Olympics in 1996 apologized on Monday.

Eric Rudolph said he did not mean to hurt anyone, he only wanted to embarrass the U.S. government.

The nail bomb that Rudoph set in Centennial Olympic Park on July 27,1996, killed a woman and injured more than 100 people.

In a sentencing hearing in a federal court in Atlanta, Rudolph said: "I sincerely hoped to achieve my objectives without harming innocent civilians."

Rudolph carried out the bombing to protest abortion.

He was led away to begin serving multiple life sentences in a maximum security federal prison. The 38-year-old survivalist will not be eligible for parole.

Rudolph agreed this year to plead guilty to the three Atlanta explosions as well as a 1998 abortion clinic bombing in Birmingham, Alabama, in a plea bargain with federal prosecutors, who agreed to drop the death penalty.

He was sentenced last month to life in prison without parole for the Birmingham bombing.

His apology on Monday came after he calmly listened to victims of the Atlanta bombings speak of the impact of his crimes.

Rudolph was on the run in the North Carolina mountains for five years until his capture in 2003.

Despite showing remorse, Rudolph insisted again on Monday that he was right to wage his own personal war against abortion clinics and the U.S. government that he said protected them. He did not explicitly mention the other three bombings, carried out in an 18-month period after the Olympic bombing.

Robert Sanderson, an off-duty police officer, was killed in the explosion at the New Woman All Women Health Care clinic in Birmingham in 1998. Emily Lyons, a nurse at the same clinic, was blinded and disfigured.

The bombs at the Sandy Springs abortion clinic and Otherside lounge in 1997 wounded about a dozen.

Prosecutors on Monday described Rudolph as a terrorist.

Rudolph, who served in the Army, disappeared into the mountains of North Carolina after the four blasts. It is believed that residents in western North Carolina, an area that resonates with anti-government sentiment, helped Rudolph or refrained from informing on him despite a large government reward.

Richard A. Jewell (December 17, 1962–August 29, 2007) was the central figure of the Centennial Olympic Park bombing at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. Jewell, working as a private security guard, discovered a pipe bomb, alerted police, and helped to evacuate the area before it exploded, saving many people from injury or potentially death. Initially hailed by the media as a hero, Jewell later was considered a suspect. Despite never being charged, he underwent what was considered by many to be a "trial by media" with great toll on his personal and professional life. Eventually he was exonerated completely: Eric Robert Rudolph was later found to have been the bomber.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Jewell

The Ballad of Richard Jewell

On July 30, 1996, the media identified Richard Jewell as the F.B.I.'s prime suspect in the Olympic Park bombing. For the first time, the 34-year-old security guard tells his extraordinary story: his brief moment as a national hero, his hounding by the Feds and the press, and his eccentric friendship with the unknown southern lawyer who helped him through his public torment.

http://www.vanityfair.com/magazine/archive/1997/02/brenner199702?currentPage=1

THE STRANGE SAGA OF RICHARD JEWELL

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,985515-1,00.html

Richard Jewell seems like the most hapless individual you could find for a contest against such powerful antagonists as the FBI and the media. An overweight, single man in his 30s, he hasn't amounted to much in life. He belongs to the one demographic group--working-class, Southern white males--about whom society still seems to allow slurs, like "bubbas." He also seems to be one of those ineffectual men who take things too far when they are given a little power. In the movies, when an an ordinary person faces great, malign forces, that person is played by Gary Cooper or Harrison Ford. Jewell seems to be a pudgy version of Barney Fife. In this mismatch, he wouldn't appear to have a chance.

Last week, however, Jewell stepped forward to claim a tremendous victory. On Oct. 26, in a highly unusual move, a federal prosecutor sent Jewell's lawyer a letter saying that Jewell is no longer a "target" in the federal investigation of the bombing at the Olympics in Atlanta last summer. For three days in July, Jewell had been a hero, since he was the security guard who had noticed the unattended knapsack containing the bomb. Then, just as suddenly, he was identified as the prime suspect and was relentlessly pursued by both the FBI and the press. So it was an emotional Jewell who held a press conference last Monday to celebrate the FBI's retreat. "For 88 days," he said, "I lived a nightmare." In tears, he thanked his mother and remembered his colleagues who were hurt. "I thank God that [the nightmare] is now ended," he said, "and that you know now what I have known all along. I am an innocent man."

The entire weight of federal law enforcement and the global media bear down on one very ordinary man, convinced that he's guilty--and it turns out he's innocent. "Richard Jewell is a poster boy for the Bill of Rights and for why we must do more to protect individual liberty," declares Mark Kappelhoff of the American Civil Liberties Union. Welcome to the real world, counters James Tierney, a former attorney general in Maine and now a legal consultant. "People get chewed up every day. The only difference in this case was that it was on national TV."

But that was enough of a difference to twist the simple plot of the little guy vs. established power. To a large extent, both the FBI and the press were justified in their actions, though nothing perhaps can justify the frenzy with which they went about their work. At the same time, Jewell has not been entirely powerless. While he saw his humdrum life demolished by the press pack, Jewell could also suddenly command a microphone at any time, and he began to put out his own bits of spin. Now he has hooked up with lawyers who plan to sue a growing list of people. The lesson may be, for these modern times, give the ordinary guy a ton of publicity--good or bad--and a couple of attorneys, and he can take on the world.

No one disputes that Jewell and his mother have come through a painful and ugly ordeal. On 60 Minutes last September, Jewell's mother described how investigators carted away the contents of her home. "They took Richard's guns...Then they took all of my Tupperware. I mean, every piece of Tupperware. They took 22 of my Walt Disney tapes." A neighbor, Mia Brown, says Richard sat on the stairs outside the apartment during the search "in just a T shirt and some shorts, looking so depressed and hurt. He just really looked pitiful." He couldn't find a job with the suspicions hanging over him, couldn't even walk the dog without a press escort.

For weeks, Jewell's lawyers had been trying to persuade the government to clear Jewell and apologize to him. The letter that finally arrived from U.S. Attorney Kent B. Alexander, the prosecutor investigating the Atlanta bombing, fell far short of an apology, but it did free Jewell from the fear that he would be arrested at any moment. Jewell, the letter stated, was "not considered a target" of the investigation. "Barring any newly discovered evidence," it continued, "this status will not change."

That language does not foreclose a future investigation of Jewell, and some FBI agents still wonder if he was somehow involved. But absolutely no evidence has been found to link him to the bombing. The search of his mother's house yielded nothing. It would be impossible to make a bomb as crude as the one at Centennial Olympic Park without handling the powder, but no trace of explosives was discovered anywhere on Jewell, in his truck or at his home, even by the vaunted devices used by the FBI that can detect one part per trillion. "They knew within days of going through his apartment that he didn't do it, but they continued to accuse him," says G. Watson Bryant Jr., one of Jewell's attorneys. "Their conduct is just despicable."

If not despicable then perhaps excessive but also understandable. The Centennial Park bomb came only 10 days after the explosion of TWA Flight 800. Nobody knew whether it marked the beginning of a reign of domestic terror. The FBI was under tremendous pressure to solve the case almost instantaneously so that the Olympic Games' athletes and visitors would not be crippled by fear. But it is common knowledge in law enforcement that "the bigger the case, the lower the standard [of conduct]," says Tierney. "The pressure on the police, on prosecutors is overwhelming."

It was perfectly proper for FBI agents to look at Jewell, because the person who reports a crime is almost always investigated. More specifically, they remembered an incident at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles in which the cop who "found" a bomb on a bus for Turkish athletes turned out to have planted it. This "modified Munchausen syndrome," in FBI terminology, occurs in someone who wants to be a hero so badly that he creates emergencies so he can rescue people. Jewell, a police wannabe, fit this profile and also had the characteristics of people who use pipe bombs--white single men in their 30s or 40s with a martial bent.

The first specific tip about Jewell came on July 27, the day of the bombing, in a phone call from Ray Cleere, the president of Piedmont College in Georgia, where Jewell had worked as a security guard until last May. Cleere said he had seen Jewell on television being acclaimed as a hero. Cleere wanted to tell the FBI that Jewell had been "a little erratic," "almost too excitable" and too gung-ho about "energetic police work."

In the next few days, FBI investigators set about gathering more information on Jewell while also pursuing other leads. Among the early allegations cited in government documents are the following: Jewell wondered aloud whether the tower he was guarding could withstand a bomb blast; a neighbor at Jewell's country cabin said he had heard a loud explosion, seen a large cloud of smoke rising from the woods and then seen Jewell at the edge of the woods, looking "very nervous"; Jewell had told co-workers, "You better take a picture of me now because I'm going to be famous"; Jewell, as a deputy sheriff in Habersham County, owned an olive-drab military-style knapsack very much like the one that contained the bomb, yet he denied this to the FBI; also, as a Habersham County deputy, Jewell had received some training about bombs, particularly pipe bombs; Jewell, who never took breaks, had left his post between 10:00 and 10:15 on the night of the bombing.

Was this information "too thin" to support a search warrant, as Jewell's lawyers claim? Not according to some experts, who note that investigators must only show "probable cause" that evidence is present to get a warrant. Yet Jewell's lawyers energetically maintain that none of these items were true. The backpack? Jewell never owned one. "He had a green knapsack he took to work every day, and they took that," says lawyer L. Lin Wood. The explosion? "Richard doesn't have a clue what they are talking about, except that he burns trash, and it could have been an aerosol can," says Wood. He points out that a government memorandum states that investigators could find no metal fragments near where the explosion supposedly took place. The boast "I'm going to be famous"? The government memorandum says the colleagues who allegedly heard this comment are still being sought, and Wood is convinced that whoever mentioned it heard about it secondhand. Taking a break? Jewell was going to the bathroom.

According to Samuel Gross, a professor of criminal procedure at Michigan Law School, "there's a point at which an open investigation of who committed a crime becomes instead the prosecution of suspect X. If that happens early on in the case, the chances of making a mistake are very great." In the Atlanta bombing, the shift from an open investigation to the prosecution of a particular suspect does seem to have taken place very early, and the result was certainly a mistake.

On July 29, only two days after the bombing, the FBI had already set about secretly taping a conversation between Jewell and a friend. Tim Attaway, an officer with the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, had got to know Jewell in the course of their work at Centennial Park. Attaway had not been there on the day of the attack, so he asked Jewell to tell him all about what happened. He went over to Jewell's mother's house for a lasagna dinner, and for nearly two hours, with barely a break, Jewell recounted the whole affair. He did not know that Attaway, at the request of the FBI, was wearing a wire. Whether it was legal or not, Jewell's lawyers maintain that it was underhanded.

More deception was in the offing. Jewell claims, and FBI sources confirm, that before his name had been leaked to the press as a suspect, agents persuaded Jewell to submit to a voluntary filmed interview by telling him they were making a training video. Officials at the Justice Department say neither they nor FBI Director Louis Freeh knew about the ruse until September. Immediately, say these sources, Justice and Freeh launched an investigation by the Office of Professional Responsibility. So far, the officials in Washington seem to agree with the opinion of Jewell attorney Jack Martin that the use of this tactic, often called a pretext interview, was "legal but sleazy."

A much more serious charge is that the agents conducting the pretext interview tried to trick Jewell into waiving his Miranda rights (the right to remain silent, to have an attorney present during questioning and so on). Jewell's lawyers say that as part of the playacting for the training video, an agent asked Jewell to sign such a waiver. Martin has released what he claims is a transcript of the interrogation that quotes an agent as saying to Jewell, "See, what I'm going to do is, I'm going to go right through it like, uh, I'm going to walk up and introduce myself to you, basically, tell you who I am, show you my credentials, just like you are doing a ... a professional interview. O.K.? And then, uh, I'll just ask you a couple of questions as far as to advise you of your rights. O.K.? Do you understand that?"

If an agent did try to fool Jewell in this way, it would unquestionably have been unlawful and improper. But there are reasons to doubt that the incident really took place. "Why in the world would you try to trick someone if you were taping it?" asks an official. "You'd have to be insane to do it with the tape running."

Confusion may have arisen because Freeh was switching signals with the field while Jewell was sitting in the FBI interview room. According to several sources, the FBI agents and prosecutors in Atlanta initially decided that they did not need to read Jewell his Miranda warning. Case law has held that a person who is speaking to the federal investigators voluntarily and who is not being detained need not be read his rights. Partway through the interview, however, Freeh called Atlanta and said agents had to give Jewell a Miranda warning. While there are conflicts about what was said when the agents did so, this much is clear: the agents did broach the subject of Miranda to Jewell--at which point Jewell decided he needed a lawyer, clammed up and left. Inside the FBI, there is criticism of Freeh's intervention. Agents speculate that if the Miranda warning had not been introduced so abruptly, Jewell might have chatted on and said enough to resolve the question of his guilt or innocence.

Instead, Jewell became the subject of an investigation that dragged on for three months, even though not one piece of physical evidence was produced. And his interrogators at the FBI will themselves face an intense internal probe, which could last a year or longer. The problems in the Jewell case only add to the bureau's recent difficulties. Last week E. Michael Kahoe, a senior FBI official, pleaded guilty to having shredded an embarrassing internal report about the mishandling of the siege at Ruby Ridge, Idaho, where the wife and son of white supremacist Randy Weaver were killed.

There is also a second internal investigation of the Jewell case going on at the FBI, and it concerns a practice that no one there defends: leaking information to the press. This investigation was launched by Freeh on Aug. 1 and aims to uncover the person or persons who tipped reporters that the FBI suspected Jewell. Freeh decreed early in his tenure that leaking is forbidden and could result in dismissal. Some have charged that the FBI was trying to use the press to squeeze Jewell, but agency officials argue persuasively that the leaks actually hurt their cause. If Jewell had not learned through the media that he was under investigation, they say, he might have been profitably strung along.

But if the FBI detests leaks, journalists live by them, and press conduct is the other great issue of the Jewell affair. Is it right to print in every newspaper and broadcast on every television station in the world the name of a man who anonymous sources have said is the subject of an investigation but who has not been arrested or charged? Is it right to explore every aspect of his life, to sit outside his home with TV cameras for weeks on end? Is it right to sacrifice an individual's privacy to the abstract principle of the public's right to know?

"This should be a day, week and month of introspection among all parts of the media," says Tom Goldstein, a professor at Berkeley's Graduate School of Journalism. "The presumption of innocence seems to have eroded, and that's the responsibility of both law enforcement and the media." It hardly matters, in Goldstein's view, that most outlets mentioned again and again that Jewell was only a suspect. "Once you put out a name, the caveats tend to get lost in the shuffle," he says.

But John Seigenthaler, chairman of the Freedom Forum First Amendment Center at Tennessee's Vanderbilt University and a former newspaper editor, says, "Given the loss of human life and the threat to human life, if the FBI gave [the name] to me, I would have gone with it. But I'd be weeping now." Not so Carl Stern, a former spokesman for the Department of Justice and correspondent for NBC who now teaches journalism at George Washington University. "All this journalistic hand-wringing is unnecessary," he says. "The System worked. There is no one in the U.S. who does not have a good picture of who Richard Jewell is, what happened to him and that he is now not a suspect in the Olympic bombing. Jewell himself had virtually unlimited access to the media."

What truly angers Jewell's lawyers is not that the press reported that he was a suspect, which after all was true, but that it did so in ways that seemed to convict him on the spot. That's why the attorneys are first targeting the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, which broke the story, and NBC in their lawsuits. Attorneys Wood and Martin criticize the Journal-Constitution for asserting, in its special edition on the bombing, that Jewell sought publicity. "By saying he tried to be a hero," says attorney Bryant, "they gave him the motive, but it's not true." Bryant Steele, an AT&T spokesman who set up Jewell's interviews after the bombing, confirms that Jewell was not particularly eager for press attention. "From the time I spent with him," he says, "I saw no evidence of it."

Jewell's lawyers also object to certain sections of the columns written by Dave Kindred for the paper. On Aug. 1, for example, Kindred compared Jewell to Wayne Williams, the Atlanta serial child killer. "Once upon a terrible time, federal agents came to this town to deal with another suspect who lived with his mother. Like this one, that suspect was drawn to the blue lights and sirens of police work. Like this one, he became famous in the aftermath of murder.

"His name was Wayne Williams.

"This one is Richard Jewell."

The Journal-Constitution would not comment on specifics but released a statement saying, "The public had--and has--a strong interest in the progress of the bombing investigation. They had a right to know when authorities' doubts about such a prominent figure in the bombing story led them to suspect him. Our reporting accurately pinpointed when those doubts turned Richard Jewell into the focus of the investigation."

As for NBC, Jewell and his lawyers object to comments made by Tom Brokaw on the day Jewell's name surfaced: "The speculation is that the FBI is close to 'making the case,' in their language. They probably have enough on him to arrest him right now, probably enough to prosecute him, but you always want to have enough to convict him as well." But Brokaw then went on to note several times that Jewell was not yet even an official suspect.

Jewell may have a hard time winning a libel suit, because he would have to prove that something written or broadcast was false. If a court decides that Jewell is a public figure, he will also have to prove that the falsehood was intentional or made in reckless disregard of the truth. This issue of whether Jewell is a public figure is "a tough borderline case," says Vincent Blasi, a First Amendment expert at the Columbia University School of Law.

Blasi agrees with the Jewell camp that the most disturbing type of coverage was "all the pop psychologizing about him." But he notes that, absent serious inaccuracies, Jewell has "a grievance but not a case." Even were Jewell to file a claim for invasion of privacy, Blasi says, it could be countered by the public's legitimate interest in whether FBI investigators had found the right person.

In fact, Jewell's lawyers say they plan to file libel actions, in which they may have little chance of prevailing. Attorney Wayne Grant insists, however, that "we will win these lawsuits. This is not a p.r. campaign." Yet it will certainly feel like one. Libel cases are a "nightmare" for the defendants, notes Blasi. "You lose them even if you win them." Already the reputations of the FBI and the press are suffering, and Jewell has been able to turn the media megaphone around to declare his innocence. You almost wish he'd quit now. Sign a lucrative book or movie deal and call it even. But it's only in films that adversity makes the ordinary man noble and merciful. In real life, he sues.

Justice Department: FBI May Have Violated Jewell's Rights

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/bombing/bombing.htm

The FBI agents who interrogated Richard Jewell in connection with the bombing at the Olympics in Atlanta last year made a "major error in judgment" and engaged in "constitutionally suspect" behavior that could have violated Jewell's rights, senior Justice Department officials said yesterday.

In his first public comments on the controversy, FBI Director Louis J. Freeh told a Senate hearing that he has since instructed the bureau's 11,000 agents not to use deceptive ploys in getting people to waive their constitutional rights.

At issue is a legally complex but everyday dilemma faced by law enforcement officers: If investigators are conducting a ruse to gain information from a suspect — such as telling the suspect that someone else is the target of the investigation — when and how do they advise the suspect of his or her constitutional rights to remain silent and to an attorney?

Following a Justice Department inquiry and FBI disciplinary proceedings, one FBI agent and one supervisor each received five-day suspensions without pay. Two other FBI officials received letters of censure.

Jewell's attorneys have repeatedly demanded more severe punishment, while a professional association representing FBI agents has argued that the punishments should be rescinded because the disciplined agents were doing their jobs in good faith and have been made scapegoats for the FBI's embarrassment over its treatment of Jewell.

At yesterday's hearing, Sen. Arlen Specter (R-Pa.) repeatedly criticized the Office of Professional Responsibility, an internal investigative arm for the Justice Department, for not explicitly stating that Jewell's constitutional rights had been violated. Specter argued that law enforcement officers around the country might be left in doubt as to what constituted proper behavior because the head of the office, Michael E. Shaheen Jr., would not draw sharp conclusions about the Jewell case.

Getting Freeh and Shaheen to admit that Jewell's rights had been violated "was tougher than extracting bicuspids," Specter said after the hearing held before the Senate Judiciary subcommittee on technology, terrorism and government information.

Jewell, who was working as a security guard during the Atlanta Olympics, discovered a suspicious green backpack hidden moments before it exploded July 27, 1996, in the crowded Centennial Olympic Park. Two people died and more than 100 people were injured as a result of the blast.

On July 30, just hours after the news media identified Jewell as a suspect in the case, FBI agents went to his apartment and asked him to come to the FBI office to help film a "training video" on how to interview "first responders" to crime scenes, Shaheen said yesterday.

Several Supreme Court decisions have allowed the use of "strategic deceptions" by law enforcement officers during investigations, and Shaheen said the use of the training video ploy "was not improper."

But the Justice Department probe concluded that Atlanta FBI officials did not advise Freeh about the ploy during a conference call between Atlanta and Washington that took place while Jewell was being questioned. Freeh said yesterday that during a subsequent call to Atlanta, "in an excess of caution," he ordered the agents to give Jewell his Miranda rights — that is, advise him of his constitutional rights, including that to an attorney.

The 1966 Miranda v. Arizona Supreme Court ruling requires police to advise people of their rights when they have been taken into custody and are being questioned in a potentially intimidating manner. Freeh and Shaheen insisted yesterday that judges would differ as to whether Jewell's interrogation required a Miranda warning.

The error of judgment by the Atlanta FBI agents arose from the manner in which they issued the warning, the officials said. After getting Freeh's order to read Jewell his rights, the agents did so but told Jewell it was for purposes of the training video. They also asked him to sign a form acknowledging receipt of the warning as if it was for the sake of the video.

One agent said to Jewell, "We're gonna use it for the purposes I told you before, but in order to do so, I want to go through it just like it's [a] real official interview, okay?" according to Shaheen's report.

Shortly afterward Jewell spoke to his attorney and ended the interview. On Oct. 26, after nearly three months under suspicion, Jewell received a letter from the FBI clearing him.

60 Minutes II: Falsely Accused

FBI Fingers Richard Jewell As Bombing Suspect

http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2002/01/02/60II/main322892.shtml

(CBS) In any high-profile federal investigation into a terrorist act, like the Sept. 11 attack on America, there are bound to be successes and failures.

Some promising leads will pan out, but also some innocent people may be swept up in the dragnet.

One American who knows all about that is Richard Jewell, who in 1996 was falsely accused of a terrorist act - setting off a bomb at the Atlanta Olympics.

In a very public investigation by the FBI and the Atlanta police, Jewell was branded "the chief suspect in the bombing."

Correpsondent Mike Wallace got to know Richard Jewell back in 1996, but it wasn't until recently that he realized how deeply affected Jewell was by his ordeal and why it's been so difficult for him to recover from what happened then.

It all began when the bomb exploded in Atlanta's Centennial Olympic Park just after 1 a.m.on July 27, 1996. Richard Jewell was working as a private security guard there and helped escort many of the spectators to safety. He was called a hero. Then everything changed.

Jewell says a headline in the Atlanta Journal Constitution that afternoon “pretty much started the whirlwind.” The headline read: FBI suspects hero guard may have planted bomb.

It was read to the world verbatim as breaking news on CNN and the AP picked it up, sending it to news organizations around the world.

The story leaked to the media was that Jewell wasn't a hero at all, but was himself the bomber who perversely sought publicity for saving people from the explosion.

“Everybody then assumed that this bizarre character, as he was being portrayed, had decided that this was gonna be his 15 minutes of fame, that he was going to set up this situation where he would literally bomb a park and then claim to be a hero,” says Lin Wood, Jewell’s lawyer.

The FBI put Jewell under round-the-clock surveillance and conducted a very public search of his apartment. All of it was broadcast on live television. It was not until many weeks later that the FBI finally acknowledged Jewell was not a suspect in the bombing.

In five years, the FBI has never apologized for the leak. “Nobody's ever called me, written me a letter, sent me an Email, called any of my attorneys,” Jewell tells Wallace.

Jewell in fact saved over 100 innocent peoples' lives that night. And no one has ever bothered to even say thanks - not the city of Atlanta, not the state of Georgia, not the Olympic Committee in Atlanta, not the International Committee.

“He's so tainted that even when he was exonerated, no one still wanted to really be identified with him,” lawyer Wood says.

Even Wood once thought Jewell was guilty. “I actually believed what I saw on television and what I read in the newspapers and I thought that the FBI had their man and the man was Richard Jewell,” Wood says.

When Wallace first met Jewell a few weeks after the bombing, Jewell was till a suspect. Wallace says he though Jewell might indeed be the bomber until Jewell described what had happened that night when he noticed a suspicious-looking package under a park bench and pointed it out to a federal ATF agent.

“He ( the ATF agent) was laying flat on his stomach and he was undoing the top of the bag with his hand and he was doing his flashlight like this and all of a sudden, he just froze,” Jewell told Wallace. “What really made me think this is, ‘oh, oh, this is bad’, is there was like a little line in training that they taught you that would instill in you, and it was, ‘if you see an ATF agent running, you better be in front of him.’”

But instead of running, Jewell stayed within 10 yards of where the package was. “We were just concerned with getting the people as far away as we could, as quickly as we could,” he says.

That summer, Jewell was besieged by the media wherever he went. And the FBI kept following him, too. When he went out for a drive, they were always there. Not just one agent in a Jeep, but a whole FBI convoy - a total of five or six FBI vehicles- which chased him on and off the Interstate The FBI also searched the home of Jewell's mother, Bobbi.

Out of her apartment they took Jewell’s guns - he hunts deer - all the Tupperware and a collection of 22 Walt Disney tapes.

Through it all, TV cameras rolled. “I felt like it was a movie production,” Mrs. Jewell says. “Every night, there must have been 20 satellite trucks in our parking lot.”

As the weeks went by, the torment by the media turned to ridicule.

Jay Leno called Jewell a “Una-doofus.” A federal agent was quoted as saying Jewell was a “Una-bubba.” His mother was called the “Una-Momma.”

In late October of 1996, the U.S. Attorney finally wrote a letter saying Jewell was not considered a target of the federal criminal investigation - a statement delivered to one of Jewell's lawyers at an out-of-the-way coffee shop, far away from the TV cameras. And unlike the very public FBI investigation of Jewell, there was no FBI press conference. Jewell and his attorney, Lin Wood, say the FBI was simply too embarrassed.

“We know a lot more than we knew at the time, when we sat down and talked with you initially,” Wood tells Wallace. “We know, for example, that the FBI was interested in Richard, but had really not decided whether Richard Jewell was a possible suspect or a potentially valuable witness. But before they could execute their plan, the banner headline gets published, and now all of a sudden, the FBI's got to come to grips with Richard Jewell in a public investigation, and that changed, I think, the whole approach that the FBI took.”

Jewell had planned to sue the FBI, but eventually decided it would be futile. He didsue a number of media organizations, and several settled for a otal believed to be in excess of $2 million dollars. The Atlanta Journal and Constitution, though, has refused to settle with Jewell, and five years after the bombing, the paper is still fighting the case in court. Attorney Peter Canfield is defending the newspaper.

"The plaintiff has consistently complained that he should never have been a suspect of the FBI in the bombing,” he says. “But he has never sued the FBI. Instead he has asserted that the Journal Constitution is to blame for all his troubles by being the first to accurately report that he had in fact become the investigation's focus."

Wood responds, “ Look, call him a suspect. Put it in your newspaper. You will not be sued for calling Richard Jewell a suspect. You will be sued when you publish in your newspaper that he's a villain, a bad man. He fits the profile of the lone bomber of the park. He sought publicity. And he's like Wayne Williams, a convicted murderer of children. Put that in your newspaper and you will be sued. That's what the Atlanta Journal and Constitution said about this man.”

For the last five years, Jewell has been trying to put his life back together. He did manage to find a job as a police officer in a small community. He lost 65 pounds and got married last September - a private affair with no TV cameras. Jewell is still just as angered at what the media did to him as he was back in 1996.

Wood says suspicion remains. “You'd be surprised,” he says, “to know how many people come up to me and will still nudge me and say, ‘Hey, so tell me, did he really do it ?’ That question is still asked.”

When he goes to a grocery store, Jewell says, people still stare, point and whisper his name.

"Driving home from work," Jewell says, "you're always looking in your rearview mirror. If you see a car there, the same car for a long time, you turn off, even though it's not your turn, to see if that car follows you. You drive different, drive a different way home every night.

"When you come out to get in your, your car in the morning, you walk around it and look under it. And you look around the parking lot to see if somebody's sitting in a car."

While it turns out Jewell was a hero, not the bomber, he's never been treated like a hero.

"I don't know what a hero's treated like," he says, "but my mother and I have never been treated like that."

Report: Richard Jewell to get more than $500,000 from NBC

jewell

Cleared Olympic bombing suspect reported 'very satisfied'

http://www.cnn.com/US/9701/03/olympic.bombing/

NEW YORK (CNN) -- Richard Jewell, the security guard who was the focus of the investigation into the Olympic bombing before he was cleared by the government, reached a settlement of more than $500,000 from NBC, The Wall Street Journal reported Friday.

When the settlement was announced on December 9, no amount was revealed and NBC issued a statement saying it agreed to the settlement to protect confidential sources and would have no further comment. Neither an apology nor a retraction was issued.

The Journal said the two sides agreed on a settlement of more than $500,000, quoting people familiar with the deal. It quoted Jewell, 34, as saying he was "very satisfied" with the settlement.

No confirmation

NBC spokeswoman Beth Comstock refused to confirm the reported amount of the settlement. And Jewell attorney Wayne Grant said, "We did not disclose the terms of the settlement to The Wall Street Journal, and I can't comment on its report."

The case centered on comments anchorman Tom Brokaw made on the air after Jewell was named a possible suspect in the July 27 blast during a concert at Atlanta's Centennial Olympic Park.

One woman was killed and more than 100 other people were injured. A cameraman on his way to cover the story died after having a heart attack.

What Brokaw said

Brokaw had said: "Look, they probably got enough to arrest him. They probably have got enough to try him." Brokaw has since emphasized that he finished his on-air remarks by saying: "Everyone, please understand absolutely he is only the focus of this investigation -- he is not even a suspect yet."

Jewell was cleared October 26.

Jewell's attorneys have twice asked The Atlanta Journal- Constitution, the first newspaper to identify Jewell, to retract the story. The newspaper has stood by its coverage and refused.

After making the deal with NBC, Jewell's lawyers met secretly with a CNN executive to discuss a settlement, The Wall Street Journal story also said. CNN declined to comment on the report.

'We're going to sue everyone'

ewell's attorneys say that while they would like some apologies, they and Jewell want financial compensation.

"We're going to sue everyone from A to Z," said attorney L. Lin Wood Jr.

"You can't spend 60 percent of an apology," he said, referring to a client's typical share of a settlement after attorneys' fees. "This litigation is not about principle. It's about compensation for injury done."

Richard Jewell v. NBC, and other Richard Jewell cases

http://medialibel.org/cases-conflicts/tv/jewell.html

Significance: These cases involved a private citizen whose name was released by the press as the FBI's main suspect in a bombing, although he had not been formally charged. There are laws prohibiting the release of suspects' names before they are charged. Also, with the exception of Jewell v. New York Post, these cases provide examples of defamation and libel per se.

Richard Jewell worked at Centennial Olympic Park during the 1996 Olympic Goodwill Games in Atlanta, Georgia when a bomb exploded, killing one and injuring several others. His name was leaked to the press by unnamed sources as the FBI's prime suspect. Media accounts of this information became the target of libel suits brought by Jewell after he was exonerated.

Richard Jewell v. NBC

This suit arose from comments made by Tom Brokaw on NBC Nightly News. Brokaw said, "The speculation is that the FBI is close to making the case. They probably have enough to arrest him right now, probably enough to prosecute him, but you always want to have enough to convict him as well. There are still some holes in this case." NBC stood by their story, but later agreed to a reported settlement of $500,000 in December 1997. They issued a statement saying they agreed on the settlement to protect confidential sources.

Other Richard Jewell Libel Cases

Richard Jewell v. Cox Enterprises (d.b.a. Atlanta Journal-Constitution)

This suit was filed in response to a report in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution naming Jewell as the FBI's prime suspect on July 30, 1997. The lawsuit charged the newspaper with libel, which portrayed Jewell as "an individual with a bizarre employment history and aberrant personality." His attorneys claimed that reports saying Jewell "fit the profile of a lone bomber" were defamatory, and partially based on false information. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution continues to support its story. The suit is pending.

Richard Jewell v. Piedmont College

Piedmont College was also named in a lawsuit for allegedly approaching media and FBI investigators with "false and defamatory statements against Jewell, his personality, and his work history at Piedmont." Jewell reportedly reached an undisclosed settlement with Piedmont in 1997. Piedmont President W. Ray Cleere had previously provided a sworn statement saying he had been misquoted. If this were the case, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution would be at fault.

Richard Jewell v. New York Post

This is a claim of libel per quod. This $15 million libel suit against the New York Post cited a cartoon drawn by Sean Delonas as an example of the newspaper's "fictionalized" version of Jewell's involvement in the Atlanta Bombing. Jewell's attorney, Lin Wood, claimed the cartoon "conveyed to the reader that an Olympic security guard was responsible for the bombing." The suit also cited a series of articles, headlines and photos which appeared in the publication. Wood said the cartoon should be viewed in context with the rest of the paper's coverage of his client.

Richard Jewell v. CNN

CNN agreed on an undisclosed settlement of a complaint brought by Jewell and his mother; CNN maintains its coverage was fair and accurate.

Richard Jewell, 44, Hero of Atlanta Attack, Dies

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/30/us/30jewell.html?hp

ATLANTA, Aug. 29 — Richard A. Jewell, whose transformation from heroic security guard to Olympic bombing suspect and back again came to symbolize the excesses of law enforcement and the news media, died Wednesday at his home in Woodbury, Ga. He was 44.

The cause of death was not released, pending the results of an autopsy that will be performed Thursday by the Georgia Bureau of Investigation. But the coroner in Meriwether County, about 60 miles southwest of here, said that Mr. Jewell died of natural causes and that he had battled serious medical problems since learning he had diabetes in February.

The coroner, Johnny E. Worley, said that Mr. Jewell’s wife, Dana, came home from work Wednesday morning to check on him after not being able to reach him by telephone. She found him dead on the floor of their bedroom, he said. Mr. Worley said Mr. Jewell had suffered kidney failure and had had several toes amputated since the diabetes diagnosis.

“He just started going downhill ever since,” Mr. Worley said.

The heavy-set Mr. Jewell, with a country drawl and a deferential manner, became an instant celebrity after a bomb exploded in Centennial Olympic Park in Atlanta in the early hours of July 27, 1996, at the midpoint of the Summer Games. The explosion, which propelled hundreds of nails through the darkness, killed one woman, injured 111 people and changed the mood of the Olympiad.

Only minutes earlier, Mr. Jewell, who was working a temporary job as a guard, had spotted the abandoned green knapsack that contained the bomb, called it to the attention of the police, and started moving visitors away from the area. He was praised for the quick thinking that presumably saved lives.

But three days later, he found himself identified in an article in The Atlanta Journal as the focus of police attention, leading to several searches of his apartment and surveillance by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and by reporters who set upon him, he would later say, “like piranha on a bleeding cow.”

The investigation by local, state and federal law enforcement officers lasted until late October 1996 and included a number of bungled tactics, including an F.B.I. agent’s effort to question Mr. Jewell on camera under the pretense of making a training film.

In October 1996, when it became obvious that Mr. Jewell had not been involved in the bombing, the Justice Department formally cleared him.

“The tragedy was that his sense of duty and diligence made him a suspect,” said John R. Martin, one of Mr. Jewell’s lawyers. “He really prided himself on being a professional police officer, and the irony is that he became the poster child for the wrongly accused.”

In 2005, Eric R. Rudolph, a North Carolina man who became a suspect in the subsequent bombing of an abortion clinic in Birmingham, Ala., pleaded guilty to the Olympic park attack. He is serving a life sentence.

Even after being cleared, Mr. Jewell said he never felt he could outrun his notoriety. He sued several major news media outlets and won settlements from NBC and CNN. His libel case against his primary nemesis, Cox Enterprises, the Atlanta newspaper’s parent company, wound through the courts for a decade without resolution, though much of it was dismissed along the way.

After memories of the case subsided, Mr. Jewell took jobs with several small Georgia law enforcement agencies, most recently as a Meriwether County sheriff’s deputy in 2005. Col. Chuck Smith, the chief deputy, called Mr. Jewell “very, very conscientious” and said he also served as a training officer and firearms instructor.

Mr. Jewell is survived by his wife and by his mother, Barbara.

Last year, Mr. Jewell received a commendation from Gov. Sonny Perdue, who publicly thanked him on behalf of the state for saving lives at the Olympics

Olympics bombing figure Richard Jewell dies

Former security guard was wrongly suspected in 1996 Atlanta incident

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/20498211/

ATLANTA - Richard Jewell, the former security guard who was erroneously linked to the 1996 Olympic bombing, died Wednesday, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation said.

Jewell, 44, was found dead in his west Georgia home, GBI spokesman John Bankhead said.

“There’s no suspicion whatsoever of any type of foul play. He had been at home sick since the end of February with kidney problems,” said Meriwether County Coroner Johnny Worley.

The GBI planned to do an autopsy Thursday, Bankhead said.

Lin Wood, Jewell’s longtime attorney, said in an e-mail to The Associated Press that he was “devastated” by the news. He declined to comment further, saying he was in New York trying to get back to Atlanta.

Jewell was initially hailed as a hero for spotting a suspicious backpack in a park and moving people out of harm’s way just before a bomb exploded during a concert at the Atlanta Summer Olympics.

The blast killed one and injured 111 others.

Three days after the bombing, an unattributed report in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution described him as “the focus” of the investigation.

Other media, to varying degrees, also linked Jewell to the investigation. He was never arrested or charged, although he was questioned and was a subject of search warrants.

As recently as last year, Jewell was working as a sheriff’s deputy.

Attorney general: We apologize

Eighty-eight days after the initial news report, U.S. Attorney Kent Alexander issued a statement saying Jewell “is not a target” of the bombing investigation and that the “unusual and intense publicity” surrounding him was “neither designed nor desired by the FBI, and in fact interfered with the investigation.”

In 1997, U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno expressed regret over the leak regarding Jewell. “I’m very sorry it happened,” she told reporters. “I think we owe him an apology.”

The Atlanta newspaper never settled a lawsuit Jewell filed against it. The case was still pending as of last year. A lawyer for the newspaper did not immediately return calls seeking comment.

Eventually, the bomber turned out to be anti-government extremist Eric Rudolph, who also planted three other bombs in the Atlanta area and in Birmingham, Ala. Those explosives killed a police officer, maimed a nurse and injured several other people.

Rudolph was captured after spending five years hiding out in the mountains of western North Carolina. He pleaded guilty to all four bombings last year and is serving life in prison.

Governor commends Jewell

Jewell told the AP last year that Rudolph’s conviction helped, but he believed some people still remember him as a suspect rather than for the two days in which he was praised as a hero.

“For that two days, my mother had a great deal of pride in me — that I had done something good and that she was my mother, and that was taken away from her,” Jewell said around the time of the 10th anniversary of the bombing. “She’ll never get that back, and there’s no way I can give that back to her.”

A year ago, Gov. Sonny Perdue commended Jewell at a bombing anniversary event. “This is what I think is the right thing to do,” Perdue declared as he handed a certificate to Jewell.

Jewell said: “I never expected this day to ever happen. I’m just glad that it did.”

Norm With Richard Jewell

![Brotherhood" (2006) [TV-Series]](http://photos1.blogger.com/x/blogger2/1421/379621144723082/211/z/425926/gse_multipart33129.jpg)

1 comment:

Here is an interesting BBC Show about the Oklahoma City Bombing. Please watch and then pass link along to friends.

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=5977554184697409940

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=5977554184697409940

Post a Comment