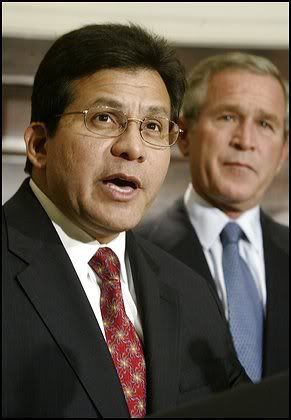

Alberto Gonzales (born August 4, 1955 in San Antonio, Texas) is an American jurist and the 80th Attorney General of the United States. Gonzales was appointed to the post in February 2005 by President George W. Bush. While Bush was Governor of Texas, Gonzales had served as his general counsel, and subsequently he served as Secretary of State of Texas and then on the Texas Supreme Court. From 2001 to 2005, Gonzales served in the Bush Administration as White House Counsel.[1] Amid several controversies and allegations of perjury before Congress, on August 27, 2007 Gonzales announced his resignation as Attorney General, effective September 17, 2007.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alberto_Gonzales

Alberto Gonzales, Political Figure / Lawyer

* Born: 4 August 1955

* Birthplace: San Antonio, Texas

* Best Known As: U.S. Attorney General, 2005-2007

Alberto Gonzales's long association with George W. Bush carried him to high political positions in Texas and then to a controversial tenure as Attorney General of the United States. A veteran of the Air Force and a Harvard Law School graduate, Gonzales began practicing law in 1982 with the Houston firm of Vinson & Elkins. Gonzales joined then-Governor Bush as general counsel in 1994, then was made Texas Secretary of State in 1997. Bush appointed him to the Texas Supreme Court in 1999. When Bush won the White House in 2000, Gonzales joined the administration as White House counsel. After Bush won a second term, Gonzales was sworn in as U.S. Attorney General on 3 February 2005, becoming the highest-ranking Hispanic-American official in the country. While at the White House, Gonzales was behind the controversial authorization of military tribunals for suspected terrorists, and given credit for a 2002 memo that downplayed the obligations of the U.S. with regard to internationally-agreed provisions against torture. (He famously referred to some provisions of the Geneva Convention as "quaint.") Critics accused Gonzales of okaying the torture of Al Qaeda or Taliban fighters; supporters said he was merely doing his job in exploring all possibilities. As Attorney General he was criticized in 2007 for firing eight federal prosecutors in what appeared to be a politically-motivated purge. A congressional investigation ensued. Gonzales announced on 27 August 2007 that he would resign as Attorney General, effective September 17th.

Gonzales succeeded John Ashcroft (2001-05) as Attorney General... Gonzales was mentioned as a possible candidate for the Supreme Court early in the Bush presidency; instead, Bush successfully nominated John Roberts and Samuel Alito in 2005... The congressional investigations of 2007 also examined the role of former White House counsel and failed Supreme Court candidate Harriet Miers.

http://www.answers.com/topic/alberto-r-gonzales

Alberto Gonzales, Attorney General

http://www.whitehouse.gov/government/gonzales-bio.html

Charlie Rose - Alberto Gonzales / Laurence Tribe

Alberto R. Gonzales

http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/people/g/alberto_r_gonzales/index.html

Alberto R. Gonzales began working for George W. Bush shortly after Mr. Bush won his first election, for governor of Texas in 1994. For most of the next decade, Mr. Gonzales worked at Mr. Bush's side, as general counsel in Texas and as chief White House counsel in Washington, acting as a quiet, dogged defender of Mr. Bush's interests who attracted little notice in either position other than as the first Hispanic to hold either job. Mr. Gonzales then became Attorney General, beginning a tenure that by its end was anything but quiet, as scandals over the firing of prosecutors and improper involvement of partisan motives in the Justice Department's workings multiplied over the course of 2007.

The common thread in the investigations that dogged Mr. Gonzales before he announced his resignation deep in the August Congressional recess was the question of whether he had continued to act as the White House's agent in a job that, unlike his previous ones, called for a measure of independence. By the time he resigned, prominent Senate Democrats had begun to raise the question of whether he should be prosecuted for perjury for testimony before Congress that they called deliberately misleading.

Before Mr. Gonzales became Attorney General, he was known mostly for his life story, which Mr. Bush compared to the American dream -- one of seven siblings in a poor family in south Texas, he attended Harvard and Rice University, eventually rising to become a member of the Texas Supreme Court.

But in Congressional testimony this year two very different images of Mr. Gonzales emerged. The first was of him repeatedly denying any recollection of a wide multitude of basic matters concerning the firing of eight United States Attorneys in Dec. 2006, including his reasons for doing so or any facts about the final meeting to decide on the dismissals; he said he could not even remember whether he had attended the meeting.

The second was the picture given by former Deputy Attorney General James B. Comey, backed up by the account of the head of the F.B.I., Robert S. Mueller III, describing a late-night hospital encounter in which they said Mr. Gonzales attempted to bully an ailing John Ashcroft, then the Attorney General, into approving a surveillance program opposed by top Justice Department officials.

Mr. Gonzales's standing on the Hill was also undermined by the shifting explanations he gave for the firing of the prosecutors. He initially insisted that the decisions were purely his, and stated flatly that the eight were removed simply because they had "lost my confidence." But e-mail messages and other documents uncovered by the Congressional investigations showed that the plan for large-scale firings had in fact originated in the White House, and had come after an examination of whether the prosecutors were "loyal Bushies," in the words of one message sent by Mr. Gonzales's chief of staff. Mr. Gonzales himself came to assert that he had played no direct role in the decision, but acknowledged that "mistakes were made."

Mr. Bush defended Mr. Gonzalez to the end, and complained that Democrats had treated him "unfairly. But for his part, when Mr. Gonzales announced his resignation, he was his usual calm and smiling self, and spoke of the distance he had traveled from his hard-scrabble roots. His worst days on the job, he said, were "better than my family's best days."

Alberto Gonzales: A timeline of events

http://www.usatoday.com/news/washington/2007-08-27-gonzales-timeline_N.htm

December 2000: Alberto Gonzales is named White House counsel by President-elect Bush, becoming the first Hispanic to hold the post.

Jan. 25, 2002: Gonzales, in a memo to Bush, says protections for prisoners outlined in the Geneva Conventions do not apply to "enemy combatants" captured in Afghanistan.

March 10, 2004: Gonzales visits an ailing Attorney General John Ashcroft in the hospital to ask him to approve the National Security Agency's warrantless surveillance program. Ashcroft refuses and defers to his deputy James Comey, who also declines.

Nov. 10, 2004: Gonzales is nominated to replace John Ashcroft as attorney general

Jan. 9, 2005: Gonzales' Chief of Staff Kyle Sampson discusses in e-mails with White House officials whether there is political will to dismiss U.S. attorneys.

FIND MORE STORIES IN: House | Congress | Senate | George W Bush | US Senate | National Security Agency | Goodling | John Ashcroft | James Comey

Feb. 3, 2005: Gonzales is confirmed by the U.S. Senate 60 to 36.

Aug. 15, 2005: Deputy AG Comey resigns.

June 2006: Justice Department aides call U.S. Attorney Bud Cummins of Arkansas to ask if he will resign to make room for Tim Griffin, a protégé of White House political adviser Karl Rove.

July 18, 2006: Gonzales testifies before the Senate that Bush personally blocked an ethics probe into the government's warrantless eavesdropping program. The program allowed the National Security Agency to bypass the courts to spy on Americans. Gonzales is one of the government officials with authority to review the program every 45 days.

Nov. 27, 2006: Gonzales meets with aide Monica Goodling, Deputy Attorney General Paul McNulty and others to discuss dismissals.

Dec. 4, 2006: White House signs off on plan to dismiss U.S. attorneys.

Dec. 7, 2006: Justice Department aides demand resignations from seven U.S. attorneys: Dan Bogden of Nevada, Paul Charlton of Arizona, Margaret Chiara of Michigan, David Iglesias of New Mexico, Carol Lam of San Diego, John McKay of Washington, and Kevin Ryan of San Francisco.

Dec. 20, 2006: Cummins resigns in Arkansas. Griffin is appointed.

Jan. 17, 2007: Under pressure from Congress, Gonzales announces that the National Security Agency's warrantless eavesdropping program is now subject to review by a secret national intelligence court.

Feb. 6, 2007: Deputy Attorney General Paul McNulty testifies that the U.S. attorney dismissals were motivated by performance, not politics, and that the White House was not involved.

March 5, 2007: Rove and other White House officials attend a meeting with Justice Department officials, including Sampson and Goodling, to review the administration's position on the U.S. atttorneys issue. Michael Battle, director of the Executive Office for U.S. Attorneys, resigns.

March 6, 2007: Six dismissed U.S. attorneys testify, including David Iglesias of New Mexico, who says he felt pressured by Rep. Heather Wilson and Sen. Pete Domenici.

March 12, 2007: Chief of Staff Sampson resigns.

March 13, 2007: Gonzales at a press conference admits "mistakes were made" in the Bush administration's firing of eight federal prosecutors and says his deputies may have given Congress an incomplete accounting of the dismissals. But he says he had little involvement with the decision to dismiss the prosecutors: "Like every CEO, I am ultimately accountable and responsible for what happens within the department. But that is in essence what I knew about the process; was not involved in seeing any memos, was not involved in any discussions about what was going on."

March 14, 2007: Sen. John Sununu, R-N.H., becomes the first Republican lawmaker to call for Gonzales to resign.

April 6, 2007: Aide Goodling resigns.

May 2, 2007: Senate subpoenas Rove e-mails.

May 10, 2007: Gonzales, testifying before Congress, admits that Rove spoke with him about voter-fraud prosecutions in three jurisdictions, including one where a U.S. attorney was ultimately fired. But he says, "My decision to ask for the resignations of these U.S. attorneys was not based on improper reasons."

May 14, 2007: McNulty announces he will resign at the end of the summer.

May 15, 2007: Former Deputy Attorney General James Comey tells a Senate panel of Gonzales' late-night hospital visit to pressure Ashcroft to approve the eavesdropping program.

May 17, 2007: Sen. Charles Schumer, D-N.Y., and Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., call for a no-confidence vote on Gonzales. The vote will not take place before mid-June.

May 21, 2007: Reps. Adam Schiff, D-Calif., and Artur Davis, D-Ala., introduce a no-confidence resolution in the House.

May 23, 2007: Former Justice Department aide Monica Goodling testifies that a conversation with Gonzales about his recollections of the dismissal of eight U.S. attorneys made her "uncomfortable."

May 24, 2007: Sen. Charles Schumer, D-N.Y., and Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., introduce a resolution calling for a no-confidence vote on Gonzales. President Bush reaffirms his support for Gonzales.

Aug. 27, 2007: Gonzales resigns.

The dismissal of U.S. Attorneys controversy is an ongoing U.S. political dispute initiated by the unprecedented midterm dismissal of seven United States Attorneys by the George W. Bush administration's Department of Justice (DOJ) on December 7, 2006, and their replacement by interim appointees under provisions of the 2005 Patriot Act reauthorization.[1][2][3][4] The dismissed U.S. Attorneys had all been appointed by President George W. Bush and confirmed by the Senate, more than four years earlier.[5][6] Other attorneys were similarly dismissed in 2005-2006; at least 26 U.S. Attorneys had been under consideration for dismissal during this time period.[7][8][9] The firings received attention via hearings in Congress in January 2007 and by March 2007 the controversy had national visibility. Attorney General Alberto Gonzales has stated that the U.S. Attorneys "serve at the pleasure of the president" and described the affair as "an overblown personnel matter."[10][11]

Congressional investigations have focused on whether the Department of Justice and the White House were using the U.S. Attorney positions for political advantage. Allegations are that some of the attorneys were targeted for dismissal to impede investigations of Republican politicians or that some were targeted for their failure to initiate investigations that would damage Democratic politicians or hamper Democratic-leaning voters.[12][13] Clear explanations for the dismissals remain elusive, however, with several administration officials providing contradictory testimony or testimony contradicted by documents subpoenaed by Congress.[14][15][16]

Critics argue that the scandal has undermined both the integrity of the Department of Justice and the nonpartisan tradition of U.S. Attorneys.[17][18][19][20] Others have gone so far as to liken the event to Watergate, referring to it as Gonzales-gate.[21]

By late-August 2007, seven senior staff of the Department of Justice had resigned, including:[22][23][24]

* Deputy Attorney General;

* Acting Associate Attorney General (who also withdrew his nomination for the office);

* Chief of Staff for the Attorney General;

* Chief of Staff for the Deputy Attorney General;

* Director of the Executive Office for U.S. Attorneys (EOUSA),

* the subsequently appointed Director to the EOUSA who was also the former acting Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Rights Division;

* and the DOJ's White House Liaison.

Many members of Congress from both parties called for the Attorney General's resignation.[25] On August 26, 2007 Alberto Gonzales submitted his letter of resignation to the president, and announced in a Department of Justice press conference on August 27, 2007 that he would resign effective September 17, 2007. Administration officials disclosed that Solicitor General Paul Clement is to become Acting Attorney General.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dismissal_of_U.S._attorneys_controversy

Ex-chief of staff Alberto Gonzales has been involved in a heated controversy over the firing of eight U.S. Prosecutors last year. Katie Couric talks about the debate.

Gonzales scandal: fired US attorney Bud Cummins replacement

Gonzales fends off senator's call that he resign

Conservative Republican says it's 'best way' to get past firings

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/18195314/

WASHINGTON - Attorney General Alberto Gonzales confronted a fresh Republican call for his resignation Thursday as he struggled to survive a withering, bipartisan Senate attack on his credibility in the case of eight fired prosecutors.

“The best way to put this behind us is your resignation,” Sen. Tom Coburn bluntly told Gonzales — one GOP conservative to another — at a daylong Senate Judiciary Committee hearing.

Gonzales disagreed and told the Oklahoma senator he didn’t know that his departure would put the controversy to rest. “I am committed to working with you in trying to restore the faith and confidence you need to work with me,” he said.

The exchange punctuated a long day in the witness chair for the attorney general, who doggedly advanced a careful, lawyerly defense of the dismissals of the federal prosecutors. He readily admitted mistakes, yet told lawmakers he had “never sought to deceive them,” and added he would make the same firings decision again.

“At the end of the day I know I did not do anything improper,” he said.

But another Republican, Sen. Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania, delivered a virtual invitation for him to step down.

He said the committee would continue its investigation and urged Gonzales to provide additional information. "If you decide to stay on it’s up to the president," he said.

Support from White House

Gonzales sat alone at the witness table in a crowded room for the widely anticipated hearing. There was no doubt about the stakes for a member of President Bush’s inner circle, and support from fellow Republicans was critical to his attempt to hold his job.

“The moment I believe I can no longer be effective I will resign as attorney general,” Gonzales said after making it clear he did not believe it had come to that.

The hearing was drawing to a close on Capitol Hill when Bush spokesman Tony Fratto told reporters at the White House, “The attorney general has the confidence of the president. ... The attorney general acted to replace the U.S. attorneys and there was nothing improper.”

Struggling to save his credibility and perhaps his job, Gonzales testified at least 45 times that he could not recall events he was asked about.

After a long morning in the witness chair, Gonzales returned after lunch to face a fresh challenge to his credibility. “Why is your story changing?” asked Sen. Charles Grassley, R-Iowa, noting that the attorney general was now accepting responsibility for the firings after initially saying he had played only a minor role.

In response, Gonzales replied that his earlier answers had been “overbroad” and the result of inadequate preparation.

The process that led to the firings “should have been more rigorous,” he added, although he repeatedly defended the decisions themselves.

Gonzales sat alone at the witness table in a crowded hearing room for the widely anticipated hearing. There was no doubt about the stakes involved for a member of President Bush’s inner circle, under pressure to resign since the dismissals of the prosecutors.

Diminishes role in firings

Gonzales insisted Thursday he played only a small role in the dismissal of eight federal prosecutors. Skeptical senators reacted with disbelief.

"We have to evaluate whether you are really being forthright," Specter bluntly informed the nation's chief law enforcement officer.

Specter said Gonzales' description was "significantly if not totally at variance with the facts."

"I don't want to quarrel with you," Gonzales replied after Specter asked again whether his was a fair, honest characterization.

Gonzales told the committee there was no impropriety in last winter's firings and the decision was "justified and should stand."

Gonzales conceded that "reasonable people might disagree" with the decision. He said the process by which the U.S. attorneys were dismissed was "nowhere near as rigorous or structured as it should have been."

Apology to attorneys

Offering an apology to the eight and their families, he also said he had "never sought to mislead or deceive the Congress or the American people" on that or any other matter.

Majority Democrats expressed skepticism at the attorney general's testimony.

"Since you apparently knew very little about the performance about the replaced United States attorneys, how can you testify that the judgment ought to stand?" asked Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, D-Mass.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., asked Gonzales whether he had reviewed the evaluation records of the dismissed prosecutors, who Justice Department officials initially said had been fired for inadequate performance. He said he had not.

The attorney general began his turn as a witness after a tongue-lashing from Sen. Patrick Leahy, the committee's chairman.

"Today the Department of Justice is experiencing a crisis of leadership perhaps unrivaled during its 137-year history," said the Vermont Democrat. "There's a growing scandal swirling around the dismissal" of prosecutors, he added.

Specter offered no more comfort in his opening remarks.

He said the purpose of the hearing was to determine whether the committee believes that Gonzales should remain in office. "As I see it, you come to this hearing with a very heavy burden of proof," Specter said as Gonzales listened intently, lips pursed, a few feet away.

Specter: ‘Not a game of gotcha’

"This is not a game of gotcha," said Specter. In a reflection of the stakes, he told the attorney general he faced the equivalent of a "reconfirmation hearing."

Protesters wearing orange garb and pink police costumes were among the spectators. The words "Arrest Gonzales" were duct-taped to their backs.

Gonzales has provided differing versions of the events surrounding the firings, first saying he had almost no involvement and then later acknowledging that his role was larger — but only after e-mails about meetings he attended were released by the Justice Department to House and Senate committees

At points, Gonzales spoke in careful, lawyerly terms.

"I now understand there was a conversation with myself and the president," he said at one point.

And responding to Specter, he seemed to differentiate between the formal bureaucratic process that led to the dismissals and his own involvement.

Democrats have stoked the controversy over the dismissals, suggesting there were political considerations involved.

Gonzales acknowledged speaking with Bush and White House adviser Karl Rove about complaints over election fraud cases in New Mexico, where David Iglesias was the U.S. attorney.

The conversation with Bush occurred on Oct. 11, Gonzales said. Iglesias' name was added to the list of those to be fired between Oct. 17 and Nov. 15 — a week after the November elections.

Critics allege that some of the eight fired were dismissed to interfere with ongoing corruption investigations in ways that might help Republicans. Gonzales strongly denies that, but Democrats have maintained that a stiff denial is insufficient without more details.

Waiting on Gonzales

The president has stuck by Gonzales, a longtime aide going back to Bush's days as governor of Texas, through calls for him to resign by several Democratic lawmakers as well as a few Republicans.

Gonzales has resisted, saying in previous prepared testimony he has "nothing to hide" but apologizing "for my missteps that have helped to fuel the controversy."

The Virginia Tech shooting that delayed the hearing for two days could have tempered the tone of the proceedings, several lawmakers said. But both Democrats and Republicans were eager to get on with the Gonzales matter.

"I think that it's appropriate to move forward," said Schumer before the hearing. Schumer is the New York Democrat leading the investigation on the Senate side.

"The sooner it's over, the better," said Sen. Orrin Hatch of Utah, whose support of Gonzales is one key to the attorney general's fate.

Republicans urged Gonzales to be more assertive and answer the questions more specifically than he did in his prepared testimony, which was released by the Justice Department on Sunday in anticipation that the hearing would be held Tuesday.

"I hope he doesn't apologize," said Rep. Chris Cannon, R-Utah, who spoke with Gonzales a week ago. "He is in a really miserable position where people are focused and saying nasty things. He thinks that he acted appropriately. I told him he ought to be less gracious in his responses."

Patrick Leahy Questions Alberto Gonzalez in Attorney Probe

Countdown: Leahy Doesn't Buy White House Lies

Will Gonzales Fall For Attorney Firings?

Sources: AG's Ouster Is Inevitable; Fired Attorney Blames Partisan Politics

http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2007/03/16/politics/main2580260.shtm

One of the eight recently fired U.S. attorneys at the center of a growing political scandal tells CBS News that he lost his job because he "did not play ball" with powerful Republicans.

"I believe, and I think all my colleagues believe, the real reason is partisan politics," the former U.S. Attorney for the District of New Mexico, David Iglesias told CBS Evening News anchor Katie Couric. "I believe I was fired because I did not play ball with two members of the Republican delegation here in New Mexico. I did not give them privileged information that could have been used in the October and November time frame."

The fallout from the firings continues to grow in Washington, and sources tell CBS News that it looks like Attorney General Alberto Gonzales will take the fall.

Republicans close to the White House tell CBS News chief White House correspondent Jim Axelrod that President Bush is in "his usual posture: pugnacious, that no one is going to tell him who to fire." But sources also said Gonzales' firing is just a matter of time.

The White House is bracing for a weekend of criticism and more calls for Gonzales to go. One source tells CBS News he's never seen the administration in such deep denial, and Republicans are growing increasingly restless for the president to take action.

The Justice Department has said the attorneys were fired for performance issues, but CBS News has also obtained performance reviews for some of the fired U.S. attorneys. Nine months before John McKay was fired as the U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Washington, he was described as an "effective, well-regarded and capable leader," Axelrod reports.

Bud Cummins, the former U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Arkansas, was called "very competent and highly regarded" in a January 2006 review obtained by CBS News.

Carol Lam, who was the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of California, was described as an "effective manager and respected leader" in February 2005.

"I got great office reviews," Iglesias told Couric. "I was not on any kind of resignation list until Nov. 15, 2006, and that was two weeks after I received two very inappropriate calls from two Republican members of Congress

Meanwhile, the White House dropped its contention Friday that former counsel Harriet Miers first raised the idea of firing U.S. attorneys, blaming "hazy memories" as e-mails shed new light on Karl Rove's role.

Presidential press secretary Tony Snow previously had asserted Miers was the person who came up with the idea, but he said Friday, "I don't want to try to vouch for origination." He said, "At this juncture, people have hazy memories."

The White House also said it needed more time before deciding whether Miers, political strategist Rove and other presidential advisers would testify before Congress.

The Justice Department said late Friday that all of the documents requested by Congress will be delivered to Capitol Hill.

"Given the importance of the issues under consideration and the presidential principles involved, we need more time to resolve them," White House spokeswoman Dana Perino said. She also said White House Counsel Fred Fielding suggested to the House Judiciary Committee that he get back to members on Tuesday.

Fielding called a staff member of the House Judiciary Committee on Thursday afternoon, saying he needed to clear the White House's position with President Bush, according to an official who works for the panel. That official spoke only on condition of anonymity because the conversation had been private.

After receiving word of the delay, committee chairman John Conyers, D-Mich., said his panel would vote next week on subpoenas for Rove, Miers and other officials.

Snow's comments came hours after the Justice Department released e-mails Thursday night pulling the White House deeper into an intensifying investigation into whether eight firings were a purge of prosecutors deemed unenthusiastic about presidential goals.

Snow said it was not immediately clear who first floated the more dramatic idea of firing all 93 U.S. attorneys shortly after President Bush was re-elected to a second term.

"This is as far as we can go: We know that Karl recollects Harriet having raised it and his recollection is that he dismissed it as not a good idea," Snow told reporters. "That's what we know. We don't know motivations. ... I don't think it's safe to go any further than that."

Asked if President Bush himself might have suggested the firings, Snow said, "Anything's possible ... but I don't think so." He said Mr. Bush "certainly has no recollection of any such thing. I can't speak for the attorney general."

"I want you to be clear here: Don't be dropping it at the president's door," Snow said.

Subpoenas demanding testimony from White House officials could come next week.

Conyers said the House Judiciary Committee "must take steps to ensure that we are not being stonewalled or slow-walked on this matter." He said, "I will schedule a vote to issue subpoenas for the documents and officials we need to talk to."

"We hope that this delay is not a signal they will not cooperate," said Sen. Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., who is leading the Senate's probe into the matter. "The story keeps changing, which neither does them or the public any good."

More Republicans called for Gonzales' ouster late in the week.

Congressman Dana Rohrbacher became the latest Republican to say Gonzales should go, reported Axelrod.

"Even for Republicans, this is a warning sign … saying there needs to be a change," said Rohrbacher. "Maybe the president should have an attorney general who is less a personal friend and more professional in his approach."

Republican Sen. John Sununu of New Hampshire has called for Bush to replace Gonzales, and a Republican member of the House Judiciary Committee, speaking on condition of anonymity, has said he plans to do the same next week.

House Democratic Whip James Clyburn of South Carolina said the controversies reflected poorly on administration officials generally.

"They don't know anything about running government. They're just political hacks," Clyburn said at a news conference in Columbia, S.C. "Gonzales is just a political hack."

Other GOP lawmakers have joined Democrats in harsh indictments of Gonzales' effectiveness but have stopped short of saying he should be fired.

"I do not think the attorney general has served the president well, but it is up to the president to decide on (Attorney) General Gonzales' continued tenure," said Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine.

The latest e-mails between White House and Justice Department officials show that Rove inquired in early January 2005 about firing U.S. attorneys. They also indicate Gonzales was considering dismissing up to 20 percent of U.S. attorneys in the weeks before he took over the Justice Department.

In one e-mail, Gonzales' top aide, Kyle Sampson, said an across-the-board housecleaning "would certainly send ripples through the U.S. attorney community if we told folks they got one term only." The e-mail concluded that "if Karl thinks there would be political will to do it, then so do I."

Sampson resigned this week amid the uproar.

The Senate Judiciary Committee has scheduled a vote for next Thursday on authorizing subpoenas for Rove, Miers and her deputy, William K. Kelley. The panel already has approved the use of subpoenas, if necessary, for Justice Department officials and J. Scott Jennings, a White House aide who works in Rove's office.

E-mails between the White House and the Justice Department suggest that Jennings was involved in setting up a meeting on a possible replacement for soon-to-be-fired New Mexico U.S. Attorney David Iglesias and in responding to "a senator problem" with the proposed replacement of Bud Cummins, then U.S. attorney for Arkansas.

Among the Justice Department officials named in the subpoenas is Associate Deputy Attorney General William E. Moschella. Lawmakers want him to testify about whether the White House consented to changing the Patriot Act last year to let the attorney general appoint new U.S. attorneys without confirmation.

In an interview with The Associated Press this week, Moschella said the change was not aimed at bypassing the Senate but ending meddling by judges in filling vacant prosecutors' jobs. Under the former law, federal judges could appoint interim U.S. attorneys in jobs that were vacant for more than 120 days.

"There's a conspiracy theory about this and it's nothing other than that," Moschella said.

Another controversy for Alberto Gonzales

The US attorney general remains in hot water as questions resurface about his role in a wiretapping program.

http://www.csmonitor.com/2007/0518/p03s03-uspo.html

WASHINGTON - First came revelations about the firing of US attorneys. Now Attorney General Alberto Gonzales is taking criticism from Congress for a second controversial subject: warrantless eavesdropping.

Specifically, key lawmakers want to know about Mr. Gonzales's possible role in an alleged fierce battle within the Bush administration itself in 2004 over the wiretapping.

Gonzales has denied that such a fight took place. Yet on May 15, Deputy Attorney General James Comey riveted a Senate hearing with his tale of a race to the hospital room of then-Attorney General John Ashcroft, where White House officials – including Gonzales – tried to pressure an ailing Mr. Ashcroft to overrule his own department and reauthorize the program.

"That night was probably the most difficult night of my professional life, so it's not something that I'd forget," Mr. Comey told the Senate Judiciary Committee.

In March 2004, Ashcroft was hospitalized with a medical condition serious enough to have him sign over control of the Justice Department to his second-in-command, James Comey.

At the time, the National Security Agency's warrantless eavesdropping program, which allowed the monitoring of the international electronic communications of people within the US suspected of links to terrorism, was up for renewal by the president. But the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel had decided that the program as it stood was illegal.

Comey was a Bush appointee and by all accounts a staunch Republican. But as a career prosecutor he decided to stand by the Justice Department's interpretation.

So the White House tried to go over his head, he said. Late in the day on March 10, 2004, a team of White House officials that included counsel Gonzales and chief of staff Andy Card raced to Ashcroft's room at George Washington University hospital. Comey beat them there, and shortly was joined by FBI Director Robert Mueller.

Gonzales entered the room and began to appeal to Ashcroft. Ashcroft then lifted his head from the pillow and pointed out in a strong voice that Comey, not he, was acting as the head of the Justice Department, and that the White House would have to deal with that fact.

"I was angry. I thought I had just witnessed an effort to take advantage of a very sick man who did not have the powers of the attorney general," Comey testified.

Eventually, Comey met with President Bush himself and engineered a compromise. The program proceeded for some weeks without Justice Department approval, but changes were then put in place to accommodate the department's concerns.

In his congressional testimony, Comey did not mention warrantless eavesdropping by name, referring instead to a "particular classified program." But the context, plus previous news reports about the hospital dispute, indicated his likely subject.

The dispute could have centered on whether the National Security Agency had proper legal oversight of the program in place, according to outside experts. It may have included the basic question of whether the president had the legal and constitutional authority to authorize such wiretaps in the first place.

"That's the backdrop of this, it seems to me. And remember, the timing of this approach to Ashcroft at the hospital was before any of this became public," says University of Richmond law professor Carl Tobias.

Comey's testimony revived the issue of one of the Bush administration's most controversial programs at a moment when Attorney General Gonzales is trying to put disputes about the firing of US attorneys behind him.

Previously, Gonzales has given carefully worded denials that an internal struggle over wiretapping took place.

In February 2006, Gonzales told the Senate Judiciary Committee that "there has not been any serious disagreement about the program that the President has confirmed. There have been disagreements about other matters regarding operations, which I cannot get into."

On May 16, four Democratic senators sent Gonzales a letter asking whether he wished to revise this testimony, in light of Comey's revelations.

Gonzales's testimony "was and remains accurate," said Justice Department spokesman Dean Boyd.

"While the attorney general provided this testimony in an unclassified setting, it is important to consider that the fact and nature of such disagreements have been briefed to the intelligence committees," Mr. Boyd said.

The next few weeks do not promise to get much easier for the embattled attorney general. Next week, his former White House liaison, Monica Goodling, is scheduled to testify before Congress under a grant of immunity.

Prior to obtaining immunity, Ms. Goodling had refused to testify on grounds of possible self-incrimination. The testimony of other officials and e-mails and other documentary evidence released by the Justice Department appear to place her at the heart of the effort to dismiss US attorneys.

Gone-zales warrantless wiretapping scandal

Alberto Gonzales Carefully Tailors Warrantless Wiretapping

The NSA warrantless surveillance controversy concerns surveillance of persons within the United States incident to the collection of foreign intelligence by the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) as part of the war on terror. Under this program, referred to by the Bush administration as the "terrorist surveillance program",[1] the NSA is authorized by executive order to monitor phone calls and other communication originating from parties outside the U.S. with known or suspected links to al Qaeda, even if the terminus of that communication lies within the U.S. Shortly before passing a new law in August of 2007 that legalized warrantless surveillance, critics in the Democratic Party contended that such "domestic" intercepts require FISC authorization under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act,[2] while the Bush administration maintains that the authorized intercepts are not domestic but rather "foreign intelligence" integral to the conduct of war and that the warrant requirements of FISA were implicitly superseded by the subsequent passage of the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF).[3]

Attorney General Alberto Gonzales confirmed the existence of the program, first reported in a December 2005 article[4][5] in The New York Times, on December 19, 2005. He stated that the program authorizes warrantless intercepts where the government "has a reasonable basis to conclude that one party to the communication is a member of al Qaeda, affiliated with al Qaeda, or a member of an organization affiliated with al Qaeda, or working in support of al Qaeda." and that one party to the conversation is "outside of the United States".[5] The revelation raised immediate concern among elected officials, civil right activists, legal scholars and the public at large about the legality and constitutionality of the program and the potential for abuse. Since then, the controversy has expanded to include the press's role in exposing a classified program, the role and responsibility of Congress in its executive oversight function and the scope and extent of Presidential powers under Article II of the Constitution.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NSA_warrantless_surveillance_controversy

CNN: Excerpts from the Gonzales Hearing on wire tapping

Gonzales defends wiretaps amid protest

Congress understood scope of program, attorney general says

http://www.cnn.com/2006/POLITICS/01/24/nsa.strategy/index.html

(CNN) -- Attorney General Alberto Gonzales had trouble tapping into a group of hooded protesters at Georgetown Law School in Washington on Tuesday.

The university was one of the stops on Gonzales' circuit as he attempts to defuse criticism of the National Security Agency's domestic spying program.

But as the attorney general tried to convey that the extraordinary circumstances of the September 11, 2001, terror attacks justified the program, the protesters turned to one of America's Founding Fathers for their rebuttal.

"Those who would sacrifice liberty for security deserve neither" -- a paraphrase of a quote attributed to Benjamin Franklin -- had been scrawled in capital letters on a sign that required four protesters to hold it up.

Gonzales didn't acknowledge the sign nor did he stop his speech as 22 protesters, including the four with the sign, stood with their backs to him during the address. Five protesters left the room during the speech. (Watch Gonzales defend the program -- 4:17)

Gonzales said that Congress was aware of the program's scope and that it had been approved "under the authorization to use military force" against terrorism.

His remarks echoed the comments of President Bush, who said Monday that he had briefed key members of Congress on the program.

Many Democrats and some Republicans have disagreed with the president's authorization of the National Security Agency to spy on U.S. citizens without a warrant.

Some lawmakers have said they weren't informed of the program's scope during briefings -- nor were they allowed to go public with concerns because of the program's sensitive nature.

The attorney general disagreed with the claim that legislators weren't told enough about the program.

"As far as I'm concerned, we have briefed the Congress," he said. "They're aware of the scope of the program."

In a speech Tuesday morning, Gonzales said the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, which bars wiretaps on Americans at home without a court warrant, did not prevent the NSA program.

"It is simply not the case that Congress in 1978 anticipated all the ways that the president might need to act in times of armed conflict to protect the United States," he said during his speech at Georgetown. "FISA, by its own terms, was not intended to be the last word on these critical issues."

Critics have questioned the administration's legal rationale, pointing to the 1978 FISA law, which requires executive branch agencies to get approval for domestic surveillance requests from a special court, whose proceedings are secret to protect national security.

They say the administration could accomplish the same goals legally by taking requests for warrants before the court under FISA. Even if the case is time sensitive, the act allows authorities to administer wiretaps immediately, as long as they go before the court within three days of the start of surveillance, they say.

Gonzales said warrantless wiretaps had been authorized by presidents in wartime since the Civil War.

"We have to remember that we're talking about a wartime foreign intelligence program," he said. "It is an early warning system with only one purpose: to detect and prevent the next attack on the United States from foreign agents hiding in our midst."

Earlier Tuesday on CNN, Gonzales sought to ease concerns that the program was tantamount to spying on Americans.

The program is aimed at "gathering up intelligence regarding al Qaeda," he said. "We're talking about communications where one end of the call is outside the United States and where there's a reasonable basis to believe that a person on the call is either a member of al Qaeda or affiliated with al Qaeda."

Gonzales said any member of Congress who thought the program was illegal "had an obligation" to say something publicly at the time they learned about it.

The American Civil Liberties Union and Center for Constitutional Rights filed lawsuits last week against the government to stop the program. (Full story)

But Gonzales said he saw no reason to believe the program would raise legal issues in the administration's war on terrorism.

"I can't speak to specific cases," he said. "What I can say is we believe the program is lawful, the information was gathered in a lawful manner and will not jeopardize any ongoing cases.

On Monday, Bush told an audience at Kansas State University in Manhattan that the congressional resolution passed in the wake of the September 11 attacks that authorized the invasion of Afghanistan and other counterterrorism measures gave him the legal authority to initiate the program.

Some critics -- including former Vice President Al Gore -- call the program illegal, contending it threatens civil liberties and privacy rights.

"You know, it's amazing that people say to me, 'Well, he was just breaking the law.' If I wanted to break the law, why was I briefing Congress?" Bush said. (Full story)

"I'm mindful of your civil liberties, and so I had all kinds of lawyers review the process," he said. "We briefed members of the United States Congress."

Former NSA chief defends wiretaps

Bush reportedly authorized the NSA to intercept communications between people inside the United States, including American citizens, and terrorist suspects overseas without obtaining a court warrant.

Bush and Gonzales weren't the only officials to stand by the program Monday. In Washington, Air Force Gen. Michael Hayden, the former NSA chief when Bush first authorized the surveillance program after 9/11, staunchly came to its defense.

"Had this program been in effect prior to 9/11, it is my professional judgment that we would have detected some of the 9/11 al Qaeda operatives in the United States, and we would have identified them as such," said Hayden, who now is principal deputy director of national intelligence.

High-level administration officials are set to make public appearances about the program this week, culminating with the president's visit Wednesday to NSA headquarters outside Washington.

The attorney general also is set to appear next month before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

GONZALES: Pressured Hospitalized Ashcroft to OK Spying

Gonzales Hospital Episode Detailed

Ailing Ashcroft Pressured on Spy Program, Former Deputy Says

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/05/15/AR2007051500864.html

On the night of March 10, 2004, as Attorney General John D. Ashcroft lay ill in an intensive-care unit, his deputy, James B. Comey, received an urgent call.

White House Counsel Alberto R. Gonzales and President Bush's chief of staff, Andrew H. Card Jr., were on their way to the hospital to persuade Ashcroft to reauthorize Bush's domestic surveillance program, which the Justice Department had just determined was illegal.

In vivid testimony to the Senate Judiciary Committee yesterday, Comey said he alerted FBI Director Robert S. Mueller III and raced, sirens blaring, to join Ashcroft in his hospital room, arriving minutes before Gonzales and Card. Ashcroft, summoning the strength to lift his head and speak, refused to sign the papers they had brought. Gonzales and Card, who had never acknowledged Comey's presence in the room, turned and left.

The sickbed visit was the start of a dramatic showdown between the White House and the Justice Department in early 2004 that, according to Comey, was resolved only when Bush overruled Gonzales and Card. But that was not before Ashcroft, Comey, Mueller and their aides prepared a mass resignation, Comey said. The domestic spying by the National Security Agency continued for several weeks without Justice approval, he said.

"I was angry," Comey testified. "I thought I just witnessed an effort to take advantage of a very sick man, who did not have the powers of the attorney general because they had been transferred to me."

The broad outlines of the hospital-room conflict have been reported previously, but without Comey's gripping detail of efforts by Card, who has left the White House, and Gonzales, now the attorney general. His account appears to present yet another challenge to the embattled Gonzales, who has strongly defended the surveillance program's legality and is embroiled in a battle with Congress over the dismissals of nine U.S. attorneys last year.

It also marks the first public acknowledgment that the Justice Department found the original surveillance program illegal, more than two years after it began.

Gonzales, who has rejected lawmakers' call for his resignation, continued yesterday to play down his own role in the dismissals. He identified his deputy, Paul J. McNulty, who announced his resignation Monday, as the aide most responsible for the firings.

"You have to remember, at the end of the day, the recommendations reflected the views of the deputy attorney general," Gonzales said at the National Press Club. "The deputy attorney general would know best about the qualifications and the experiences of the United States attorneys community, and he signed off on the names," he added.

Those comments appear to differ, at least in emphasis, from earlier remarks by Gonzales, who has previously laid much of the responsibility for the dismissals on his ex-chief of staff, D. Kyle Sampson. They stand in contrast to testimony and statements from McNulty, who has acknowledged signing off on the firings but has told Congress he was surprised when he heard about the effort.

The Justice Department and White House declined to comment in detail on Comey's testimony, citing internal discussions of classified activities.

The warrantless eavesdropping program was approved by Bush after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. It allowed the NSA to monitor e-mails and telephone calls between the United States and overseas if one party was believed linked to terrorist groups. The program was revealed in late 2005; Gonzales announced in January that it had been replaced with an effort that would be supervised by a secret intelligence court.

The crisis in March 2004 stemmed from a review of the program by the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel, which raised "concerns as to our ability to certify its legality," according to Comey's testimony. Ashcroft was briefed on the findings on March 4 and agreed that changes needed to be made, Comey said.

That afternoon, Ashcroft was rushed to George Washington University Hospital with a severe case of gallstone pancreatitis; on March 9, his gallbladder was removed. The standoff between Justice and White House officials came the next night, after Comey had refused to certify the surveillance program on the eve of its 45-day reauthorization deadline, he testified.

About 8 p.m. on March 10, Comey said that his security detail was driving him home when he received an urgent call from Ashcroft's chief of staff, David Ayres, who had just received an anxious call from Ashcroft's wife, Janet. The White House -- possibly the president -- had called, and Card and Gonzales were on their way.

Furious, Comey said he ordered his security detail to turn the car toward the hospital, careening down Constitution Avenue. Comey said he raced up the stairs of the hospital with his staff, beating Card and Gonzales to Ashcroft's room.

"I was concerned that, given how ill I knew the attorney general was, that there might be an effort to ask him to overrule me when he was in no condition to do that," Comey said, saying that Ashcroft "seemed pretty bad off."

Mueller, who also was rushing to the hospital, spoke by phone to the security detail protecting Ashcroft, ordering them not to allow Card or Gonzales to eject Comey from the hospital room.

Card and Gonzales arrived a few minutes later, with Gonzales holding an envelope that contained the executive order for the program. Comey said that, after listening to their entreaties, Ashcroft rebuffed the White House aides.

"He lifted his head off the pillow and in very strong terms expressed his view of the matter, rich in both substance and fact, which stunned me," Comey said. Then, he said, Ashcroft added: "But that doesn't matter, because I'm not the attorney general. There is the attorney general," and pointed at Comey, who was appointed acting attorney general when Ashcroft fell ill.

Later, Card ordered an 11 p.m. meeting at the White House. But Comey said he told Card that he would not go on his own, pulling then-Solicitor General Theodore Olson from a dinner party to serve as witness to anything Card or Gonzales told him. "After the conduct I had just witnessed, I would not meet with him without a witness present," Comey testified. "He replied, 'What conduct? We were just there to wish him well.' "

The next day, as terrorist bombs killed more than 200 commuters on rail lines in Madrid, the White House approved the executive order without any signature from the Justice Department certifying its legality. Comey responded by drafting his letter of resignation, effective the next day, March 12.

"I couldn't stay if the administration was going to engage in conduct that the Department of Justice had said had no legal basis," he said. "I just simply couldn't stay." Comey testified he was going to be joined in a mass resignation by some of the nation's top law enforcement officers: Ashcroft, Mueller, Ayres and Comey's own chief of staff.

Ayres persuaded Comey to delay his resignation, Comey testified. "Mr. Ashcroft's chief of staff asked me something that meant a great deal to him, and that is that I not resign until Mr. Ashcroft was well enough to resign with me," he said.

The threat became moot after an Oval Office meeting March 12 with Bush, Comey said. After meeting separately with Comey and Mueller, Bush gave his support to making changes in the program, Comey testified. The administration has never disclosed what those changes were.

Bush Dodges the Ashcroft Hospital Visit Question

Embattled AG now accused in teen sex scandal 'cover-up'

Attorney General Gonzales among officials who allegedly ignored abuse of minor boys

http://www.worldnetdaily.com/news/article.asp?ARTICLE_ID=54861

Attorney General Alberto Gonzales and U.S. Attorney Johnny Sutton, both already under siege for other matters, are now being accused of failing to prosecute officers of the Texas Youth Commission after a Texas Ranger investigation documented that guards and administrators were sexually abusing the institution's teenage boy inmates.

Among the charges in the Texas Ranger report were that administrators would rouse boys from their sleep for the purpose of conducting all-night sex parties.

Ray Brookins, one of the officials named in the report, was a Texas prison guard before being hired at the youth commission school. As a prison guard, Brookins had a history of disciplinary and petty criminal records dating back 21 years. He retained his job despite charges of using pornography on the job, including viewing nude photos of men and women on state computers.

The Texas Youth Comission controversy traces back to a criminal investigation conducted in 2005 by Texas Ranger Brian Burzynski. The investigation revealed key employees at the West Texas State School in Pyote, Texas, were systematically abusing youth inmates in their custody.

Burzynski presented his findings to the attorney general in Texas, to the U.S. Attorney Sutton, and to the Department of Justice civil rights division. From all three, Burzynski received no interest in prosecuting the alleged sexual offenses.

"This case demonstrates that a partisan political agenda, with Karl Rove in an orchestrating role, has penetrated the Justice Department and subverted fair-minded administration of the law," Matt Angle, director of the Lone Star Project, told WND.

It's just the latest controversy for Sutton, Gonzales and the Bush administration's direction of the Justice Department. Earlier, Sutton's decisions to prosecute two Border Patrol agents and Deputy Sheriff Gil Hernandez were criticized as having been influenced by the intervention of the Mexican government.

Gonzales is under heavy congressional pressure in the controversy over the recent forced resignations of eight U.S. attorneys. At issue is whether the Bush administration is directing the Justice Department to pursue politically motivated prosecutions at the expense of fair or even-handed law enforcement.

In the Texas Youth Commission scandal, Texas Ranger official Burzynski received a July 28, 2005, letter from Bill Baumann, assistant U.S. attorney in Sutton's office, declining prosecution on the argument that under 18 U.S.C. Section 242, the government would have to demonstrate that the boys subjected to sexual abuse sustained "bodily injury." Baumann wrote that, "As you know, our interviews of the victims revealed that none sustained 'bodily injury.'"

Baumann's letter continued, adding a definition of the phrase "bodily injury," as follows: "Federal courts have interpreted this phrase to include physical pain. None of the victims have claimed to have felt physical pain during the course of the sexual assaults which they described."

Baumann's letter further suggested that insufficient evidence existed to prove the offenders in the Texas Youth Commission case had used force in their alleged acts of pedophilia: "A felony charge under 18 U.S.C. Section 242 can also be predicated on the commission of 'aggravated sexual abuse' or the attempt to commit aggravated sexual abuse. The offense of aggravated sexual abuse is proven with evidence that the perpetrator knowingly caused his victim to engage in a sexual act (which can include contact between the mouth and penis) by using force against the victim or by threatening or placing the victim in fear that the victim (or any other person) will be subjected to death, serious bodily injury or kidnapping. I do not believe that sufficient evidence exists to support a charge that either Brookins or Hernandez used force to cause victims to engage in a sexual act."

Baumann's letter went so far as to suggest that the victims may have willingly participated in, or even enjoyed, the acts of pedophilia involved: "As you know, consent is frequently an issue in sexual assault cases. Although none of the victims admit that they consented to the sexual contact, none resisted or voiced any objection to the conduct. Several of the victims suggested that they were simply 'getting off' on the school administrator."

Baumann's letter also rejected Burzynski's charges that the administrators at the Texas Youth Commission facility in West Texas had used their position of authority to force the inmates to participate in the sexual acts or that the administrators had lengthened the sentences of the boys to retain willing participants or punish those reluctant to participate.

Baumann wrote: "In order for the government to be successful in a criminal prosecution, it would be essential for us to show that the victim was in fact victimized. Most of the victims were aware of the power that the school principal and assistant superintendent held over them, but none were able to describe retaliative acts committed by either the principal or assistant superintendent. Although it is apparent that many students were retained at West Texas State School long after their initial release date, it would be difficult to prove that either Mr. Brookins or Mr. Hernandez prevented their release."

On Sept. 27, 2005, the U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division declined prosecution in a letter written to Lemuel Harrison, the Texas Youth Commission superintendent at the West Texas State School.

In that letter, Justice Department section chief Albert Moskowitz wrote that "evidence does not establish a prosecutable violation of the federal criminal civil rights statutes."

Angle maintains the decision not to prosecute was purely political.

"The U.S. attorney's office in Texas actually prepared indictments in this case," Angle told WND. "But when the word came from Washington, that's when Baumann wrote his letter declining prosecution. Sutton's office dropped the matter on the desk of the local district attorney, but nobody from Sutton's office said 'if you can’t go on this case, we'll help you out.'"

WND asked Angle to explain how politics drove the decisions not to prosecute.

"If you read the letters from Sutton's office or from DOJ, it's really amazing what abuse they describe and then downplay as not being serious," Angle explained. "They describe systematic and widespread abuse of juveniles who were held in these facilities by the people who were administering these facilities, and they acknowledge this fully, yet they determine that the evidence is not sufficient to warrant federal prosecution."

Angle explained to WND that he found both letters shocking.

"The letters justify not pursuing these cases because, number one, there is no evidence that any of these juveniles felt physical pain while they were being assaulted, and the letters use the word 'assaulted,'" he said. "And then also, they rejected prosecution because none of these juveniles stated in the investigations that they resisted and objected, which of course the facts of the report show to be the case. This case developed right in the middle of Governor Perry's 2006 re-election campaign. While Texas is a Republican state, and the Republicans expected to win, still at that time, Governor Perry was facing an election challenge from Carole Strayhorn, a third party candidate who was also a former Republican comptroller in Texas."

He continued: "I would speculate that the political powers in Texas and Washington in the Republican Party were not interested in this sex scandal coming to light. Sutton and Gonzales let their political responsibilities outstrip their legal responsibilities, and as a result you had children who were in danger of sexual abuse and were left in that danger."

Angle says that while the U.S. Justice Department and Texas attorney general's office were not prosecuting in this case, they were actively pursuing minor voter fraud issues with only a handful of allegations to go on.

On March 2, 2007, Governor Rick Perry appointed Jay Kimbrough, his former staff chief and homeland security director, to serve as "special master" to lead an investigation into the Texas Youth Commission sex abuse scandal. Shortly thereafter, the commission stopped a hiring practice that had allowed convicted felons to work as administrators in the system. The practice had involved a requirement that prior criminal records be destroyed for employees hired by the commission.

On March 17, 2007, the entire Texas Youth Commission governing board resigned.

The Texas Youth Commission is the state's juvenile corrections agency, charged "with the care, custody, rehabilitation, and reestablishment in society of Texas' most chronically delinquent or serious juvenile offenders." Inmates are felony-level offenders between the age of 10 and 17 when they are committed. The commission can maintain jurisdiction over offenders until their 21st birthdays.

The Lone Star Project is organized as a political research and policy analysis project of the Lone Star Fund, a federal political action committee organized in Texas. The Lone Star Project has aggressively investigated alleged political abuses within the Texas Republican Party, including playing a leading role in investigating the activities of former Rep. Tom DeLay in the redistricting controversy in Texas.

Bill Baumann was the lead prosecutor in another controversial case. In a case eerily reminiscent of the controversial jailing of Border Patrol agents Jose Compean and Ignacio Ramos while the illegal-alien drug-smuggler they wounded went free, Texas Deputy Sheriff Gilmer Hernandez is imprisoned for a year for an altercation with illegal aliens. Baumann urged he get the maximum seven-year sentence.

Alberto Gonzales Death Penalty Case Questioning

Fired US Attorney Paul Charlton Speaks to Jason Leopold

Fired Prosecutor Says Gonzales Pushed Death Penalty

Figures Show Attorney General Often Overrules U.S. Attorneys' Arguments Against Capital Charges

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/06/27/AR2007062702310.html

Paul K. Charlton, one of nine U.S. attorneys fired last year, told members of Congress yesterday that Attorney General Alberto R. Gonzales has been overzealous in ordering federal prosecutors to seek the death penalty, including in an Arizona murder case in which no body had been recovered.

Justice Department officials had branded Charlton, the former U.S. attorney in Phoenix, disloyal because he opposed the death penalty in that case. But Charlton testified yesterday that Gonzales has been so eager to expand the use of capital punishment that the attorney general has been inattentive to the quality of evidence in some cases -- or the views of the prosecutors most familiar with them.

"No decision is more important for a prosecutor than whether or not to . . . deliberately and methodically take a life," Charlton said. "And that holds true for the attorney general."

His testimony before a Senate Judiciary subcommittee reviewing the use of the federal death penalty provided the most detailed account to date of Charlton's interactions with Gonzales's aides about the murder case that contributed to his dismissal. It also was one of the most pointed critiques of Gonzales by any of the fired federal prosecutors, whose removal touched off a furor on Capitol Hill.

Justice Department data presented at the hearing demonstrated that the administration's death penalty dispute with Charlton was not unique. The Bush administration has so far overruled prosecutors' recommendations against its use more frequently than the Clinton administration did. The pace of overrulings picked up under Gonzales's predecessor, Attorney General John D. Ashcroft, and spiked in 2006, when the number of times Gonzales ordered prosecutors to seek the death penalty against their advice jumped to 21, from three in 2005.

Barry M. Sabin, deputy assistant attorney general for the department's criminal division, testified, "I don't know and haven't evaluated the circumstances of the numbers." He added: "There should be great respect for those who are most familiar with the facts of the case, the co-defendants and the local community." But by law, the attorney general has final say over whether capital charges are filed.

According to Charlton, the case on which he clashed with Gonzales involved a methamphetamine dealer named Jose Rios Rico, who was charged with slaying his drug supplier. Charlton said he believed the case, which has not yet gone to trial, did not warrant the death penalty because police and prosecutors lacked forensic evidence -- including a gun, DNA or the victim's body. He said that the body was evidently buried in a landfill and that he asked Justice Department officials to pay $500,000 to $1 million for its exhumation.

The department refused, Charlton said. And without such evidence, he testified, the risk of putting the wrong person to death was too high.

Charlton said that in prior cases, Ashcroft's aides had given him the chance to discuss his recommendations against the death penalty, but that Gonzales's staff did not offer that opportunity. He instead received a letter, dated May 31, 2006, from Gonzales, simply directing him to seek the death penalty.

Charlton testified that he asked Justice officials to reconsider and had what he called a "memorable" conversation with Deputy Attorney General Paul J. McNulty. Michael J. Elston, then McNulty's chief of staff, called Charlton to relay that the deputy had spent "a significant amount of time on this issue with the attorney general, perhaps as much as five to 10 minutes," and that Gonzales had not changed his mind. Charlton said he then asked to speak directly with Gonzales and was denied.

Last August, D. Kyle Sampson, then Gonzales's chief of staff, sent Elston a dismissive e-mail about the episode that said: "In the 'you won't believe this category,' Paul Charlton would like a few minutes of the AG's time." The next month, Charlton's name appeared on a list of prosecutors who should be fired, which Sampson sent to the White House.

In April, Gonzales testified in Congress that Charlton had used "poor judgment in pushing forward a recommendation on a death penalty case." An internal Justice Department memo, laying out the reasons each prosecutor had been fired, said Charlton had shown "repeated instances of defiance, insubordination."

At least one former Justice Department official has expressed a different view. James B. Comey, deputy attorney general under Ashcroft, testified last month that Charlton once had persuaded him not to pursue the death penalty. "Paul Charlton was a very experienced -- still is very smart, very honest and able person," Comey told lawmakers. "And I respected him a great deal and would always listen to what he had to say."

Alberto Gonzales Resigns

Attorney General Gonzales Resigns

Attorney General Alberto Gonzales Announces His Resignation

http://abcnews.go.com/Politics/wireStory?id=3527851

Alberto Gonzales, the nation's first Hispanic attorney general, announced his resignation Monday ending a nasty, monthslong standoff over his honesty and competence at the helm of the Justice Department.

Republicans and Democrats alike had demanded his resignation over the botched handling of FBI terror investigations and the firings of U.S. attorneys, but President Bush had defiantly stood by his Texas friend until accepting his resignation Friday.

"It has been one of my greatest privileges to lead the Department of Justice," Gonzales said, announcing his resignation effective Sept. 17.

Bush planned to discuss Gonzales' departure at his Crawford, Texas, ranch today.

Solicitor General Paul Clement will be acting attorney general until a replacement is found, said the officials who spoke on condition of anonymity to avoid pre-empting the announcement.

Homeland Security chief Michael Chertoff was among those mentioned as possible successors. However, a senior administration official said the matter had not been raised with Chertoff. Bush leaves Washington next Monday for Australia, and Gonzales' replacement might not be named by then, the official said.

"Better late than never," said Democratic presidential candidate John Edwards, summing up the response of many in Washington to Gonzales' resignation.

Gonzales served more than two years as the nation's first Hispanic attorney general.

Bush steadfastly and at times angrily refused to give in to critics, even from his own GOP, who argued that Gonzales should go. Earlier this month at a news conference, the president grew irritated when asked about accountability in his administration and turned the tables on the Democratic Congress.

"Implicit in your questions is that Al Gonzales did something wrong. I haven't seen Congress say he's done anything wrong," Bush said testily.

Gonzales, 52, called Bush on Friday to inform him of his resignation, according to a senior administration official who spoke on condition of anonymity to not pre-empt Gonzales' statement. The president had Gonzales come to lunch at his ranch on Sunday as a parting gesture.

Gonzales, whom Bush once considered for appointment to the Supreme Court, is the fourth top-ranking administration official to leave since November 2006. Donald H. Rumsfeld, an architect of the Iraq war, resigned as defense secretary one day after the November elections. Paul Wolfowitz agreed in May to step down as president of the World Bank after an ethics inquiry. And top Bush adviser Karl Rove earlier this month announced that he was stepping down.

Reacting to Monday's developments, Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy, D-Vt., said that Gonzales' department had "suffered a severe crisis of leadership that allowed our justice system to be corrupted by political influence."

Gonzales could not satisfy critics who said he had lost credibility over the Justice Department's handling of warrantless wiretaps related to the threat of terrorism and the firings of several U.S. attorneys.

As attorney general and earlier as White House counsel, Gonzales pushed for expanded presidential powers, including the eavesdropping authority. He drafted controversial rules for military war tribunals and sought to limit the legal rights of detainees at Guantanamo Bay prompting lawsuits by civil libertarians who said the government was violating the Constitution in its pursuit of terrorists.

There were indications that the development came suddenly. Bush normally handles Cabinet resignations with efficiency, only allowing news of them to leak when a successor has been chosen and appearing with both the person departing and the replacement when the public announcement was made. That was not to be the case this time, the official said.

"Alberto Gonzales was never the right man for this job. He lacked independence, he lacked judgment, and he lacked the spine to say no to Karl Rove," said Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev.

"This resignation is not the end of the story. Congress must get to the bottom of this mess and follow the facts where they lead, into the White House," Reid warned.

The flap over the fired prosecutors proved to be the final straw for Gonzales, whose truthfulness in testimony to Congress was drawn into question.

Lawmakers said the dismissals of the federal prosecutors appeared to be politically motivated, and some of the fired U.S. attorneys said they felt pressured to investigate Democrats before elections. Gonzales maintained that the dismissals were based the prosecutors' lackluster performance records.

Thousands of documents released by the Justice Department show a White House plot, hatched shortly after the 2004 elections, to replace U.S. attorneys. At one point, senior White House officials, including Rove, suggested replacing all 93 prosecutors. In December 2006, eight were ordered to resign.

In several House and Senate hearings into the firings, Gonzales and other Justice Department officials failed to fully explain the ousters without contradicting each other.

During his congressional testimony, Gonzales answered "I don't know" and "I can't recall" scores of times and even some Republicans said his testimony was evasive. Bush, however, praised Gonzales' performance and said the attorney general was "honest" and "honorable."

U.S. attorneys serve at the pleasure of the president, and can be removed. But congressional Democrats said politics played an unusually critical role in the ouster of several prosecutors.

In 2004, Gonzales pressed to reauthorize a secret domestic spying program over the Justice Department's protests. Gonzales was White House counsel at the time and during a dramatic hospital confrontation he and then-White House chief of staff Andrew Card sought approval from then-Attorney General John Ashcroft, who was in intensive care. Ashcroft refused.

The White House subsequently reauthorized the program without the department's approval. Later, Bush ordered changes to the program to help the department defend its legality. The domestic surveillance program was later declared unconstitutional by a federal judge and since has been changed to require court approval before surveillance can be conducted.

Similarly, Gonzales found himself on the defensive in early March for FBI's improper and, in some cases, illegal prying into Americans' personal information during terror and spy probes. On March 9, the Justice Department's inspector general released an audit showing that FBI agents, over a three-year period, demanded telephone and Internet companies to hand over their customers' personal information without official authorization.

The damning audit also found that the FBI had improperly obtained telephone records in non-emergency circumstances, and concluded that it underreported to Congress how often it used national security letters to ask businesses to turn over customer data. The letters are administrative subpoenas that do not require a judge's approval.

Gonzales declared himself upset and frustrated over the findings. But lawmakers said they had begun to lose confidence in him.

AP White House Correspondent Terence Hunt and Associated Press Writer Lara Jakes Jordan contributed to this report from Peru, Vt.

Hardball: Gonzales Resigns

Gonzales Exit Spurs GOP Relief, Dems' Hope

President Says Embattled Attorney General's Name Was "Dragged Through The Mud"

http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2007/08/27/politics/main3206267.shtml

(CBS/AP) Attorney General Alberto Gonzales' resignation Monday after months of draining controversy drew expressions of relief from Republicans and a vow from Democrats to pursue their investigation into fired federal prosecutors.

Gonzalez called President Bush Friday evening, reports CBS White House correspondent Bill Plante, then traveled to Texas to sit down with the president and the First Lady at the ranch.

Insiders say the decision was Gonzales' own, adds Plante, though he was well aware that the president's top advisers thought his departure was in the president's best interest.

Mr. Bush, Gonzales' most dogged defender, told reporters he had accepted the resignation reluctantly. "His good name was dragged through the mud for political reasons," Bush said.

The president named Paul Clement, the solicitor general, as a temporary replacement. With less than 18 months remaining in office, there was no indication when Bush would name a successor, or how quickly or easily the Senate might confirm one.

Apart from the president, there were few Republican expressions of regret following the departure of the nation's first Hispanic attorney general, a man once hailed as the embodiment of the American Dream.

"Our country needs a credible, effective attorney general who can work with Congress on critical issues," said Sen. John Sununu of New Hampshire, who last March was the first GOP lawmaker to call on Gonzales to step down. "Alberto Gonzales' resignation will finally allow a new attorney general to take on this task."