Jesus' Life here on Earth

Jesus of Nazareth, Biblical Figure / Religious Figure

http://www.answers.com/topic/jesus-christ

* Born: c. 5 B.C.

* Birthplace: Bethlehem, Judea

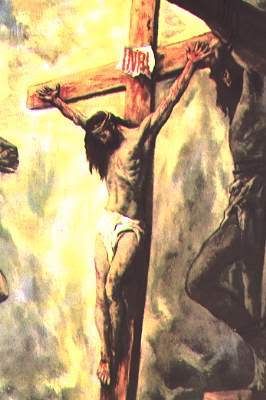

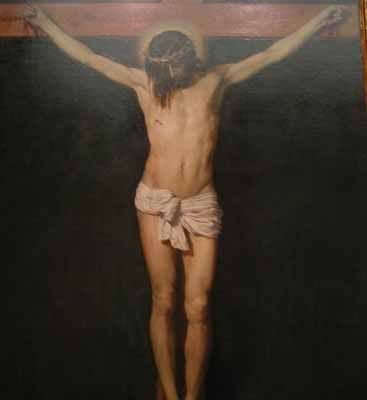

* Died: c. 30 A.D. (crucifixion)

* Best Known As: The son of God in the Christian religion

Jesus of Nazareth is the central figure of the Christian religion, a savior believed to be both God incarnate and a human being. He is also known as Jesus Christ, the term "Christ" meaning anointed or chosen one. Most of the details of his life are unclear, and much of what is known about his life comes from the four Gospels of the Bible. The Gospels tell the story of Jesus's miraculous birth in a stable in Bethlehem, and then of his life as an adult, a teacher with miraculous powers who foretold his own death to his closest followers, called apostles. Jesus, betrayed by the apostle Judas, was crucified by the Romans, and his resurrection three days after his death was taken as proof of his divinity. The date of Jesus's miraculous birth to Mary is celebrated each December 25th as Christmas Day. The occasion was used as the base year for the modern Christian calendar, though researchers now believe that earlier estimates were inexact and that Jesus was actually born between 4 B.C. and 7 B.C. The date of the crucifixion is now marked as Good Friday, and the resurrection celebrated as Easter.

Jesus of Nazareth was portrayed by actor Jim Caviezel in the 2004 film The Passion of the Christ. Others who have played Jesus on the big screen include Jeffrey Hunter (King of Kings, 1961), Max von Sydow (The Greatest Story Ever Told, 1965) and Willem Dafoe (The Last Temptation of Christ, 1988)... Christmas is also the realm of the fictional toy-giver known as Santa Claus.

Jesus (8–2 BC/BCE to 29–36 AD/CE),[1] also known as Jesus of Nazareth, is the central figure of Christianity. He is also called Jesus Christ, where "Jesus" is an Anglicization of the Greek Ίησους (Iēsous), itself a Hellenization of the Hebrew יהושע (Yehoshua) or Hebrew-Aramaic ישוע (Yeshua), meaning "YHWH is salvation"; and where "Christ" is a title derived from the Greek christós, meaning the "Anointed One," which corresponds to the Hebrew-derived "Messiah."

The main sources of information regarding Jesus' life and teachings are the four canonical Gospels of the New Testament: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Most scholars in the fields of history and biblical studies agree that Jesus was a Galilean Jew, was regarded as a teacher and healer, was baptized by John the Baptist, and was crucified in Jerusalem on orders of the Roman Governor Pontius Pilate under the accusation of sedition against the Roman Empire.[2][3] Very few scholars believe that all ancient texts concerning Jesus are either completely accurate or completely inaccurate concerning Jesus' life.[4]

Christian views of Jesus (see also Christology) center on the belief that Jesus is the Messiah whose coming was promised in the Old Testament and that he was resurrected after his crucifixion. Christians predominantly believe that Jesus is God incarnate, who came to provide salvation and reconciliation with God. Nontrinitarian Christians profess various other interpretations regarding his divinity (see below). Other Christian beliefs include Jesus' Virgin Birth, performance of miracles, fulfillment of biblical prophecy, ascension into Heaven, and future Second Coming.

In Islam, Jesus (Arabic: عيسى, commonly transliterated as Isa) is considered one of God's most beloved and important prophets, a bringer of divine scripture, a worker of miracles, and the Messiah. Muslims, however, do not share the Christian belief in the crucifixion or divinity of Jesus. Muslims believe that Jesus' crucifixion was a divine illusion and that he ascended bodily to heaven. Most Muslims also believe that he will return to the earth in the company of the Mahdi once the earth has become full of sin and injustice at the time of the arrival of Islam's Antichrist-like Dajjal.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jesus

Timeline During Life of Jesus

http://www.jesuscentral.com/ji/historical-jesus/jesus-lifetime.php

Timeline

6-4 BC • Birth of Jesus Christ

5-4 BC • Escape to Egypt. Slaughter of children.

4 BC • Herod the Great dies (spring).

7-8 AD • Jesus visits Jerusalem as a child.

12 AD • Augustus makes Tiberius co-regent.

14 AD • Tiberius becomes Caesar (August 19th).

25 AD • Pilate & Caiaphas appointed to office.

29 AD • Ministry of John the Baptist begins.

29 AD • Christ's ministry begins.

31 AD • Tiberius executes Sejanus (Oct 18th).

33 AD • Jesus dies (Friday, April 3rd, 3:00pm).

36 AD • Pilate dethroned. Caiaphas deposed.

37 AD • Tiberius Caesar dies.

Jesus, Judas and Da Vinci: What Is the Truth?

THE TRIAL OF JESUS CHRIST AND THE LAST SUPPER

http://www.crimelibrary.com/notorious_murders/classics/jesus_trial/7.html

Jesus's life

http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity/history/jesus_1.shtml

Jesus: Fact or Fiction?

http://www.jesusfactorfiction.com/

This FRONTLINE series is an intellectual and visual guide to the new and controversial historical evidence which challenges familiar assumptions about the life of Jesus and the epic rise of Christianity.

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/

Truth About the Jesus

From Jesus to Christ

How did a Jewish prophet come to be seen as the Christian savior? The epic story of the empty tomb, the early battles and the making of a great faith.

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/7244999/site/newsweek/

The story, it seemed, was over. Convicted of sedition, condemned to death by crucifixion, nailed to a cross on a hill called Golgotha, Jesus of Nazareth had endured all that he could. According to Mark, the earliest Gospel, Jesus, suffering and approaching the end, repeated a verse of the 22nd Psalm, a passage familiar to first-century Jewish ears: "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?" There was a final, wordless cry. And then silence.

Why have you forsaken me? From the Gospel accounts, it was a question for which Jesus' disciples had no ready answer. In the chaos of the arrest and Crucifixion, the early followers had scattered. They had expected victory, not defeat, in this Jerusalem spring. If Jesus were, as they believed, the Jewish Messiah, then his great achievement would be the inauguration of the Kingdom of God on earth, an age marked by the elimination of evil, the dispensation of justice, the restoration of Israel and the general resurrection of the dead.

Instead, on the Friday of this Passover, at just the moment they were looking for the arrival of a kind of heaven on earth, Jesus, far from leading the forces of light to triumph, died a criminal's death. Of his followers, only the women stayed as Jesus was taken from the cross, wrapped in a linen shroud and placed in a tomb carved out of the rock of a hillside. A stone sealed the grave and, according to Mark, just after the sun rose two days later, Mary Magdalene and two other women were on their way to anoint the corpse with spices. Their concerns were practical, ordinary: were they strong enough to move the stone aside? As they drew near, however, they saw that the tomb was already open. Puzzled, they went inside, and a young man in a white robe—not Jesus—sitting on the right side of the tomb said: "Do not be amazed; you seek Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified. He has risen; he is not here, see the place where they laid him." Absorbing these words, the women, Mark says, "went out and fled from the tomb; for trembling and astonishment had come upon them; and they said nothing to any one, for they were afraid."

And so begins the story of Christianity—with confusion, not with clarity; with mystery, not with certainty. According to Luke's Gospel, the disciples at first treated the women's report of the empty tomb as "an idle tale, and ... did not believe them"; the Gospel of John says that Jesus' followers "as yet ... did not know ... that he must rise from the dead."

From Jesus to Christ

For many churchgoers who fill the pews this Holy Week, re-enacting the Passion, contemplating the cross and celebrating the Resurrection, the faith may appear seamless and monumental, comfortably unchanging from age to age. In a new NEWSWEEK Poll, 78 percent of Americans believe Jesus rose from the dead; 75 percent say that he was sent to Earth to absolve mankind of its sins. Eighty-one percent say they are Christians; they are part of what is now the world's largest faith, with 2 billion believers, or roughly 33 percent of the earth's population.

Yet the journey from Golgotha to Constantine, the fourth-century emperor whose conversion secured the supremacy of Christianity in the West, was anything but simple; the rise of the faith was, as the Duke of Wellington said of Waterloo, "the nearest-run thing you ever saw in your life." From the Passion to the Resurrection to the nature of salvation, the basic tenets of Christianity were in flux from generation to generation as believers struggled to understand the meaning of Jesus' mission.

Jesus is a name, Christ a title (in Hebrew, Messias, in Greek, Christos, meaning "anointed one"). Without the Resurrection, it is virtually impossible to imagine that the Jesus movement of the first decades of the first century would have long endured. A small band of devotees might have kept his name alive for a time, even insisting on his messianic identity by calling him Christ, but the group would have been just one of many sects in first-century Judaism, a world roiled and crushed by the cataclysmic war with Rome from 66 to 73, a conflict that resulted in the destruction of Jerusalem

So how, exactly, did the Jesus of history, whom many in his own time saw as a failed prophet, come to be viewed by billions as the Christ of faith whom the Nicene Creed says is "the only-begotten Son of God ... God of God, Light of Light, Very God of very God ... by whom all things were made"? And why did Christianity succeed where so many other religious and spiritual movements failed?

The questions are nearly 2,000 years old, yet in this culturally divisive American moment, a time when believers feel besieged and skeptics think themselves surrounded, a reconstruction of Jesus' journey from Jewish prophet to Christian savior suggests that faith, like history, is nearly always more complicated than it seems. For the religious, the lesson is that those closest to Jesus accepted little blindly, and, in the words of Origen of Alexandria, an early church father, "It is far better to accept teachings with reason and wisdom than with mere faith." For the secular, the reminder that Christianity is the product of two millennia of creative intellectual thought and innovation, a blend of history and considered theological debate, should slow the occasional rush to dismiss the faithful as superstitious or simple.

As the sun set on the Friday of the execution, Jesus appeared to be a failure, his promises about the Kingdom of God little more than provocative but powerless rhetoric. No matter what Jesus may have said about sacrifice and resurrection during his lifetime, the disciples clearly did not expect Jesus to rise again. The women at the tomb were stunned; confronted with the risen Lord, Thomas initially refused to believe his eyes; and at the end of Matthew's Gospel, some disciples still "doubted."

Their skepticism is hardly surprising. Prevailing Jewish tradition did not suggest that God would restore Israel and inaugurate the Kingdom through a condemned man who went meekly to his death. Quite the opposite: the Messiah was to fight earthly battles to rescue Israel from its foes and, even if this militaristic Messiah were to fall heroically in the climactic war, then documents found at Qumran (popularly known as the Dead Sea Scrolls) suggest that another "priestly" Messiah would finish the affair by putting the world to rights. Re-creating the expectations of first-century Jews, Paula Fredriksen, Aurelio Professor of Scripture at Boston University, notes: "Like the David esteemed by tradition, the Messiah will be someone in whom are combined the traits of courage, piety, military prowess, justice, wisdom and knowledge of the Torah. The Prince of Peace must first be a man of war: his duty is to inflict final defeat on the forces of evil." There was, in short, no Jewish expectation of a messiah whose death and resurrection would bring about the forgiveness of sins and offer believers eternal life.

Yet a sacrificial, atoning role is precisely the one the first followers of Jesus believed he had played in the world. In the earliest known writing in the New Testament, the apostle Paul writes that Jesus "gave himself for our sins to deliver us from the present evil age, according to the will of God the Father."

Where did this interpretation of Jesus' mission come from? Like the New Testament authors, conservative believers often argue that Jesus is the Christ "according to the Scriptures" of the Old Testament—that the Hebrew Bible does in fact envision a messianic sacrificial lamb who will redeem the sin of Adam. There is a general argument that all of Biblical history had led to the Crucifixion and Resurrection, and then there are what scholars call specific "prooftexts" (including Isaiah, Daniel, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Hosea, among others) in which the early Christians found foreshadowings of Jesus' life and mission. Yet anyone reading the ancient Israelite texts outside the Christian tradition may not necessarily interpret them as prologue to the New Testament; the Biblical books have their own histories and tell their own stories. To think that Christianity negates God's covenant with Israel, meanwhile, is misguided and contrary to canonical apostolic teaching. God's choice of the Jewish people is eternal, Paul writes, no matter what: "... as regards election they are beloved for the sake of their forefathers ... the gifts and the call of God are irrevocable."

Christianity does owe the basic elements of its creed to Jewish tradition: atoning sacrifice; a messiah; a general resurrection of the dead. Until Jesus, however, no one had ever, apparently, woven these threads together in the way the apostles did after the Resurrection. ("Messiah" appears fewer than 40 times in the Old Testament, and when it does, it refers to an earthly king, not an incarnate savior from sins.) The heart of the matter was, as Paul wrote in First Corinthians (circa 50): "For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received, that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day ..."

From the beginning, critics of Christianity have dismissed the Resurrection as a theological invention. As a matter of history, however, scholars agree that the two oldest pieces of New Testament tradition speak to Jesus' rising from the dead. First, the tomb in which Jesus' corpse was placed after his execution was empty; if it were not, then Christianity's opponents could have produced his bones. (Matthew also says the temple priests tried to bribe Roman guards at the tomb, saying, "Tell people, 'His disciples came by night and stole him away while we were asleep'"—implying the body was in fact gone.)

The second tradition is that the apostles, including Paul, believed the risen Jesus had appeared to them; writing in the first years after the Passion, Paul lists specific, living witnesses, presumably in order to encourage doubters to seek corroborating testimony. Paul seems quite clear about what the skeptical would find if they checked his story. Less clear is what we should make of the later, differing Gospel accounts of the discovery of the empty tomb and the appearances of the risen Jesus. Sometimes he appears as flesh and blood; at others, he can walk through walls. Sometimes he is instantly recognized; at others, even close followers fail to understand whom they are speaking with until Jesus identifies himself. Most likely the post-Resurrection stories represent different traditions within the nascent faith. The contrasting details do not help the Christian case on logical grounds, but the Gospel renderings do affirm that the tomb was empty, and that believers thought the resurrected Jesus had appeared to some of them for a time.

Written after Paul, the Gospels speak of sacrifice, redemption and resurrection. Yet we cannot responsibly skate around the Gospel reports that the disciples were initially mystified by the Resurrection. What explains the skeptical disciples' transformation from fear and wonder to clarity and conviction about the empty tomb and its significance in the history of salvation—that through his death and resurrection Jesus would redeem humankind?

Perhaps recollections of the words of Jesus himself. Though many scholars rightly raise compelling questions about the historical value of the portraits of Jesus in the Gospels, the apostles had to arrive at their definition of his messianic mission somehow, and it is possible that Jesus may have spoken of these things during his lifetime—words that came flooding back to his followers once the shock of his resurrection had sunk in. On historical grounds, then, Christianity appears less a fable than a faith derived in part from oral or written traditions dating from the time of Jesus' ministry and that of his disciples. "The Son of man is delivered into the hands of men, and they shall kill him; and after that ... he shall rise the third day," Jesus says in Mark, who adds that the disciples at the time "understood not that saying, and were afraid to ask him."

That the apostles would have created such words and ideas out of thin air seems unlikely, for their story and their message strained credulity even then. Paul admitted the difficulty: "... we preach Christ crucified, a stumbling-block to Jews and folly to Gentiles." A king who died a criminal's death? An individual's resurrection from the dead? A human atoning sacrifice? "This is not something that the PR committee of the disciples would have put out," says Dr. R. Albert Mohler Jr., president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky. "The very fact of the salvation message's complexity and uniqueness, I think, speaks to the credibility of the Gospels and of the entire New Testament."

Jesus' words at the last supper—that bread and wine represented his body and blood—now made more sense: he was, the early church argued, a sacrificial lamb in the tradition of ancient Israel. Turning to the old Scriptures, the apostles began to find what they decided were prophecies Jesus had fulfilled. Hitting upon the 53rd chapter of Isaiah, they interpreted the Crucifixion as a necessary portal to a yet more glorious day: "... he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities ... and with his stripes we are healed." In the Book of Acts, Peter is able to preach a sermon in which Jesus is connected to passages from Isaiah, Joel and the Psalms.

Skepticism about Christianity was widespread and understandable. From a Jewish perspective, the first-century historian Josephus noted: "About this time there lived Jesus, a wise man. He worked surprising deeds and was a teacher ... He won over many Jews and many of the Greeks ... And the tribe of Christians, so called after him, has not disappeared to this day." In a separate reference, Josephus writes of "James the brother of the so-called Christ." A good Jew of the priestly caste, Josephus is not willing to grant Jesus the messianic title. In Athens, Stoic and Epicurean philosophers asked Paul to explain his message. "May we know what this new teaching is which you present?" they asked. "For you bring some strange things to our ears ..." They heard him out, but the Resurrection was too much of a reach for them. In the second century, the anti-Christian critic Celsus called the Resurrection a "cock-and-bull story," and cast doubt on the eyewitness testimony: "While he was alive he did not help himself, but after death he rose again and showed the marks of his punishment and how his hands had been pierced. But who say this? A hysterical female, as you say, and perhaps some other one of those who were deluded by the same sorcery, who either dreamt in a certain state of mind and through wishful thinking had a hallucination due to some mistaken notion ... or, which is more likely, wanted to impress others by telling this fantastic tale ...

But why invent this particular story unless there were some historical basis for it—either in the remembered words of Jesus or in the experience of the followers at the tomb and afterward? "Once a man has died, and the dust has soaked up his blood," says Aeschylus' Apollo, "there is no resurrection." Citing the quotation, N. T. Wright, the scholar and Anglican Bishop of Durham, notes that various ancients may have believed in the immortality of the soul and a kind of mythic life in the underworld, but the stories about Jesus had no direct parallel. And while Jews believed in a general resurrection as part of the Kingdom (Lazarus and others raised by Jesus were destined to die again in due course), Wright adds that "nowhere within Judaism, let alone paganism, is a sustained claim advanced that resurrection has actually happened to a particular individual."

The uniqueness—one could say oddity, or implausibility—of the story of Jesus' resurrection argues that the tradition is more likely historical than theological. Either from a "revelation" from the risen Jesus or from the reports of the earliest followers, Paul "received" a tradition that the resurrection was the hinge of history, the moment after which nothing would ever be the same. "If Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is in vain and your faith is in vain ..." Paul writes. "Lo! I will tell you a mystery. We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet."

At this distance, such passages are stirring and have the glow of victory about them, but Jesus can be confounding, and he forced the early believers to become masters of theological improvisation. First the Kingdom failed to materialize at the time of the Passion, forcing the disciples—at least the male ones—into hiding. Next came the initially mystifying Resurrection. Then came ... nothing. A central prophecy preached in Jesus' name, his Second Coming on "clouds of glory," failed to happen. "Truly, I say to you," Jesus tells his disciples in Mark, "there are some standing here who will not taste death before they see the kingdom of God come with power."

And yet, as the decades of the first century came and went, the world wore on. In writing the Gospels, and then in formulating church doctrine in the second, third and fourth centuries, Jesus' followers reacted to his failure to return by doing what they arguably did best, for by now they had a good bit of practice at it: they reinterpreted their theological views in light of their historical experience. If the kind of kingdom they had so long expected was not at hand, then Jesus' life, death and resurrection must have meant something different. The Christ they had looked for in the beginning was not the Christ they had come to know. His kingdom was not literally arriving, but he had, they came to believe, created something new: the church, the sacraments, the promise of salvation at the last day—whenever that might be. The shift of emphasis from the short to the long term was an essential achievement. Because they believed Jesus' resurrection had given them the keys to heaven, the hour of his coming mattered less, for God was worth the wait. Drawing on imagery in Isaiah, John the Divine evoked the ultimate glory in his Revelation: "And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away. And he that sat upon the throne said, Behold, I make all things new."

Not everyone saw the same visions. There were many different Christian groups at first, including Gnostic believers, some of whom, contrary to other apostolic traditions, thought Jesus was more divine than human. According to Yale historian Jaroslav Pelikan, Gnostic doctrine was noted for its "denial that the Savior was possessed of a material, fleshly body." Ignatius of Antioch, a second-century bishop, ferociously argued the opposite, writing that Jesus "was really born, and ate and drank, was really persecuted by Pontius Pilate, was really crucified and died ... [and] really rose from the dead." Such a view had to be the case to track with the early understanding that, as Paul wrote, Jesus "was descended from David according to the flesh." Among the faithful, the notion that God would manifest himself in human form and subject himself to pain and death inspired martyrdom and suffering. Writing about Rome under Nero, Tacitus reported that Christians "were crucified or set on fire so that when darkness came they burned like torches in the night."

Still, the faith, intensely focused on Jesus, endured. "In Jesus Christ, Christianity gave men and women a new love, a very compelling story, and it meant becoming part of a rich, dense community," says Robert Louis Wilken, professor of the history of Christianity at the University of Virginia. In his book "The Rise of Christianity," the sociologist Rodney Stark calculates that the number of Christians rose from roughly 1,000 (or .0017 percent of the Roman Empire) in A.D. 40 to nearly 34 million in 350 (or 56.5 percent of the total population). Stark argues that once the early church "decided not to require converts to observe the [Jewish] Law, they created a religion free of ethnicity," a religion attractive not only to Gentiles but to the Jews of the wider Roman world. Christians also benefited from their own charity work. In an age of plagues, they took care of the sick; the apostate Emperor Julian hated the "Galileans" and their "support not only [for] their poor, but ours as well." Such mission work attracted converts, Stark says, as did the church's decision to value women. And by largely banning abortion and female infanticide, Christians increased the ranks of women who could in turn bear Christian children.

Numbers tell only part of the story. Whatever one thinks of Christianity, the history of Jesus gave birth to a new, lasting vision of the origins and destiny of human life, a vision drawn from the religion's deep roots in Judaism. Everyone is created in God's image; there is, as Paul said, "neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus"; all are equal, special, worthy. In the Christian world view, says the Roman Catholic theologian George Weigel, "we are not congealed stardust, an accidental byproduct of cosmic chemistry. We are not just something, we are someone." The promise at the heart of the faith: that God, as the fourth-century church father Athanasius said, "was made man that we might be made gods."

So many theological questions linger, and always will: Did Jesus understand his relationship to God the Father in the way Christians now do? Luke claims he did: "The Son of man must suffer many things, and be rejected ..." Jesus says, "and be slain, and be raised the third day." Did he grasp his atoning role? John claims he did: "I am the living bread which came down from heaven; if any one eats of this bread, he will live for ever; and the bread which I shall give for the life of the world is my flesh." But how much of this is remembered history, and how much heartfelt but unhistorical theology? It is impossible to say. "How unsearchable are his judgments," Paul writes of the Lord, "and how inscrutable his ways!" And they will remain mysterious until believers, in Paul's words, come "face to face" with God.

In the meantime, we are left with an exhortation from a favorite text of Saint Augustine's, the 105th Psalm: "Seek the Lord, and his strength: seek his face evermore." As the search goes on for so many along so many different paths, Paul offers some reassuring words for the journey: "Be at peace among yourselves ... encourage the faint-hearted, help the weak, be patient with them all. See that none of you repays evil for evil, but always seek to do good to one another and to all. Rejoice always, pray constantly, give thanks ... hold fast what is good, abstain from every form of evil"—wise words for all of us, whatever our doubts, whatever our faith.

A Portrait of Faith

With 'Jesus of Nazareth,' Pope Benedict XVI fights back against 'the dictatorship of relativism' by showing the world his vision of the definitive truth of Christ.

http://today.msnbc.msn.com/id/18629187/site/newsweek/page/0/

ho was Jesus, really? It has become acceptable, even fashionable, lately to speak of the Christian Lord in casual terms, as though he were an acquaintance with a mysterious past. Pope Benedict's trip to Brazil last week revived an old retelling of the Christian story in which Jesus is cast as a social revolutionary determined to overthrow the established order. The massive success of "The Da Vinci Code" reflected the hunger of millions to see Jesus as a regular person—a man with a wife and a child, a popular teacher whose true life story was subverted by the corporate self-interest of the early church. A look at any best-seller list reveals a thriving subcategory of readable scholarly and pseudo-scholarly books about the "real" Jesus: he was, they claim, a sage, a mystic, a rabbi, a boyfriend. He was a father, a pacifist, an ascetic, a prophet. In some parts of the Christian world, the aspects of Jesus' story that most strain credibility—the virgin birth and the physical resurrection—have become optional to faith.

One can almost hear Pope Benedict XVI roaring with frustration at this multiplicity of interpretations. Benedict, a theologian by training with an expertise in dogma, has been fierce in his condemnation of the creep of Western secularism, and the promiscuity of recent Jesus scholarship must seem to him another symptom of the same disease, all ill-founded and subjective claims. "We are building a dictatorship of relativism," he declared at the beginning of the 2005 enclave that elected him pope, "that does not recognize anything as definitive and whose ultimate goal consists solely of one's own ego and desires." Benedict's answer to secularism is Christ, and this week the American publisher Doubleday releases "Jesus of Nazareth," Benedict's portrait of his Lord. It is an orthodox biography—one that acknowledges the role of analytical scholarship while in fact leaving little room for a critical interpretation of Scripture. This approach is not surprising, given Benedict's job description, but in a world where Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris and other proponents of secularism credit belief in Jesus as one of the sources of the world's ills, Benedict offers an unvarnished opposing view: belief in Jesus, he says, is the only thing that will save the world.

And so, in a way, in the big bookstores and Amazon.com rankings, the ancient war between believers and nonbelievers begins anew. Liberal Catholics worry that, in spite of assurances to the contrary, Benedict is writing an "official" biography, and they have cause for concern. Benedict has been notoriously disapproving of unauthorized views of Jesus; he helped John Paul II crush the liberation theologists in Central America in the 1980s and more recently suspended an American priest for writing a book about Jesus that he said did not give sufficient credence to the resurrection. But for orthodox Christian believers, Benedict's book is a gift—a series of homilies on the New Testament by a masterful Scriptural exegete. In NEWSWEEK's exclusive excerpt, the pope explicates Jesus' baptism by John—a story that appears in all four Gospel accounts and that modern historians believe is at least partially grounded in fact. Benedict starts by describing the social and historical backdrop of the time, and the common use of ritual ablutions among first-century Jews. His picture of John the Baptist reflects the scholarly consensus in most respects; the Baptist was an ascetic who likely spent time with the Essenes, a group of Jews who lived in the desert awaiting the imminent arrival of the Messiah.

(Benedict is notably silent, though, on the Baptist as an apocalyptic preacher and on the probability that Jesus also believed that the world was about to end in flames. In a discussion elsewhere in "Jesus of Nazareth," Benedict goes to lengths to show that when Jesus said, "The Kingdom of God is at hand," he didn't mean the apocalypse. What he meant, the pope writes, is that "God is acting now—this is the hour when God is showing himself in history as its Lord." This interpretation may be profound and in keeping with Benedict's Christ-centered message; it is not, many scholars would say, historically accurate.)

In one of the excerpt's most affecting scenes, Benedict describes the hordes of sinners he imagines standing on the banks of the Jordan River waiting for baptism. Jesus waits among them. Morphing from historian to pastor, Benedict asks the question that so many Sunday-school teachers have asked before him: as the Son of God, why would Jesus need to be purified? "The real novelty is the fact that he—Jesus—wants to be baptized, that he blends into the gray mass of sinners waiting on the banks of the Jordan," writes Benedict. "Baptism itself was a confession of sins and the attempt to put off an old, failed life and to receive a new one. Is that something Jesus could do?"

With that, the senior theologian steps in, the man whose job for two decades was to defend Catholic doctrine to the world. Jesus' descent into the water is a symbolic foreshadowing, Benedict explains, of his death and resurrection—and the resurrection he promises to all his followers. In the ancient Middle East, water represents death; it also represents life. With his baptism, "Jesus loaded the burden of all mankind's guilt upon his shoulders; he bore it down into the depths of the Jordan," Benedict writes. "He inaugurated his public activity by stepping into the place of sinners. His inaugural gesture is an anticipation of the Cross. He is, as it were, the true Jonah who said to the crew of the ship, 'Take me and throw me into the sea'."

What of the next part of the story? The part where Jesus rises from the water, the heavens part, the Spirit descends on his shoulders (in the shape of a dove) and God's voice says, "This is my Son, the Beloved, in whom I am well pleased." Does Benedict believe, as the fundamentalists do, that this literally happened? George Weigel, the theologian and papal biographer, imagines that something very important happened that day—what, exactly, he does not know. Benedict is asking readers to see Scripture as inspired but not dictated by God, Weigel explains, and to see the New Testament narrators as real people grappling with "the extreme limitations of the describable." For Benedict, the starting point is faith.

"Jesus of Nazareth," then, will not bring unbelievers into the fold, but courting skeptics has never been Benedict's priority. Nor will his portrait join the lengthy list of Jesus biographies so eagerly consumed by the non-orthodox—the progressive Protestants and "cafeteria Catholics" who seek the truth about Jesus in noncanonical places like the Gnostic Gospels. Moderates may take "Jesus of Nazareth" as something of a corrective to fundamentalism because it sees the Bible as "true" without insisting on its being factual. Mostly, though, "Jesus of Nazareth" will please a small group of Christians who are able simultaneously to hold post-Enlightenment ideas about the value of rationality and scientific inquiry together with the conviction that the events described in the Gospels are real. "This is about things that happened," explains N. T. Wright, the Anglican Bishop of Durham who is perhaps the world's leading New Testament scholar. "It's not just about ideas, or people's imaginations. These are things that actually happened. If they didn't happen, you might still have interesting ideas, but it wouldn't be Christianity at the end of the day."

Faith may actually be the most productive approach to finding truth in Scripture; the historical method has so far gleaned very little in the way of facts. Jesus left no diaries, and he had no contemporary Boswell. The best accounts of his life, the Gospel stories, were written at least 30 years after his death by men who believed he was God; other corroborating evidence of his life is scanty at best. For more than 1,500 years, no one even thought to seek the "truth" about Jesus. For Christians, Jesus was the truth.

The Enlightenment saw the revolutionary beginnings of the 300-year quest for the historical Jesus. For the first time, scholars began to look at the Bible critically, as a series of stories written by time-bound people with biases and agendas of their own. Thomas Jefferson announced that the "true" sayings of Jesus were as easily distinguishable "as diamonds in a dunghill," and set to work in the evenings sorting them out. Nineteenth- and 20th-century scholars tried to unearth the facts of Jesus' life by studying the first-century Roman-Jewish world. New Testament stories were true, they decided, if they "fit" into the first-century context. Stories were also true, the scholars said, if they didn't fit at all—if they so strained credibility that no sane and pious narrator would include them unless he had to.

Using these and other more conventional methods of verification, scholars came up with a few spindly facts about the man so many people call Christ. Jesus of Nazareth, a Jew, ministered in Judea sometime between 28 and 33. He was baptized; a member of his own band betrayed him. He was charged with a political crime: the Romans put KING OF THE JEWS on his cross. He was buried and followers said he appeared to them after his death. No one saw him rise again, though there are reports his tomb was empty. "We learned from the search for the historical Jesus that the search for the historical Jesus is not going to take us very far," says Alan Segal, professor of religion at Barnard College.

Nevertheless, in the last 30 years the speed and intensity of that search has escalated—starting with the Jesus Seminar, a group of scholars who, like Jefferson, tried to weed the authentic sayings of Jesus from the inauthentic and ending most recently with the largely discredited "discovery" of Jesus' family tomb in a Jerusalem suburb. Archeology is the new frontier—untold dollars are being spent digging in Israel, looking for evidence of Jesus and his times. Not all these efforts can be said to be futile: while the search for the historical Jesus has given us very little about Jesus, it has given us a rich picture of the world in which he lived, a multicultural world of elites and peasants, of tyranny and impulses for freedom, a world where people struggled to balance their instincts for assimilation against their own religious roots—a world, in other words, very much like our own. Benedict's portrait may contribute little to our historical understanding of Jesus, but what he does give is a window into his own, passionate and uncompromising faith, a faith that faces constant challenge in the world of ideas. Let the battles begin.

Did Jesus walk on water? Or ice?

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/12152740/

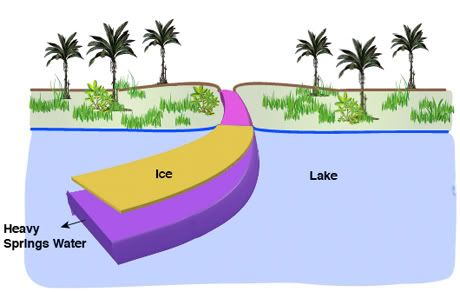

Rare conditions could have conspired to create hard-to-see ice on the Sea of Galilee that a person could have walked on back when Jesus is said to have walked on water, a scientist reported Tuesday.

The study, which examines a combination of favorable water and environmental conditions, proposes that Jesus could have walked on an isolated patch of floating ice on what is now known as Lake Kinneret in northern Israel.

Looking at temperature records of the Mediterranean Sea surface and using analytical ice and statistical models, scientists considered a small section of the cold freshwater surface of the lake. The area studied, about 10,000 square feet (930 square meters), was near salty springs that empty into it.

The results suggest temperatures dropped to 25 degrees Fahrenheit (-4 degrees Celsius) during one of the two cold periods 2,500 to 1,500 years ago for up to two days, the same decades during which Jesus lived.

With such conditions, a floating patch of ice could develop above the plumes, resulting from the salty springs along the lake's western shore in Tabgha. Tabgha is the town where many archeological findings related to Jesus have been found.

"We simply explain that unique freezing processes probably happened in that region only a handful of times during the last 12,000 years," said Doron Nof, a Florida State University professor of oceanography. "We leave to others the question of whether or not our research explains the biblical account."

Nof figures that in the last 120 centuries, the odds of such conditions on the low-latitude Lake Kinneret are most likely 1-in-1,000. But during the time period when Jesus lived, such “springs ice” may have formed once every 30 to 60 years.

Such floating ice in the unfrozen waters of the lake would be hard to spot, especially if rain had smoothed its surface.

"In today's climate, the chance of springs ice forming in northern Israel is effectively zero, or about once in more than 10,000 years," Nof said.

The findings are detailed in April's issue of the Journal of Paleolimnology.

Did Jesus learn what he knew from India

Jesus in Kashmir,India

'Jesus Dynasty': Were There Two Messiahs?

Scholar Also Argues Historical Evidence Shows Jesus Had a Human Father

http://abcnews.go.com/Nightline/story?id=1815838

Israel remains a land of holiness and of controversy -- and not just in political terms.

Almost by the month, religious scholars and historians propose a new way of understanding the life and impact of Jesus Christ. In his new book "The Jesus Dynasty," James Tabor is the latest addition to this hotly contested catalog.

Tabor, a historian with the Religious Studies Department at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte, has spent his entire career studying the life of Jesus. He says his new book is the culmination of 40 years of research.

"I first traveled to the Holy Land with my parents over 40 years ago," Tabor told "Nightline." "It was that experience that set me on my lifelong quest for the historical Jesus."

His conclusions are certain to provoke intense controversy and skepticism among other scholars and followers of the Christian faith. Tabor argues the historical evidence shows that Jesus had a human father, and that he was joined by a fellow messiah.

We took Tabor back to where it all started, the city of Jerusalem, to assess the major claims in his book.

'Unbelievable' Discovery

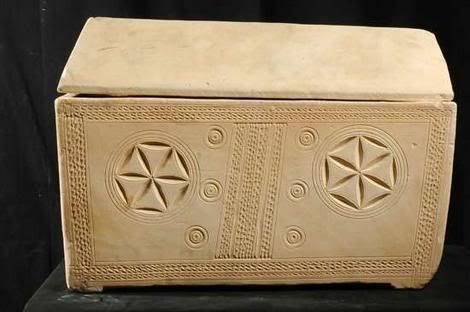

We began our journey at the location of Tabor's most remarkable archaeological discovery: an ancient hillside tomb outside Jerusalem that had been recently ransacked.

Inside, there were compartments hewn from ancient stone where corpses had been laid to rest. They were empty, apart from one that appeared to contain an old newspaper laid out within the chamber. In fact, it was a burial shroud -- a linen fabric into which a corpse would have been placed. Test results proved almost beyond Tabor's wildest dreams.

"We had to believe the unbelievable," he said. "We had stumbled upon the only example of a burial shroud from the first century."

Analysis showed the shroud had contained the remains of a first-century man who died of tuberculosis. In the same tomb, Tabor's group also found an ossuary -- a box used to contain the bones of the deceased -- that had the name Miriam or Mary inscribed upon it. Tabor also believes the recently discovered ossuary of James, which some scholars have dismissed as a forgery, may have also originated in this tomb.

"There's some circumstantial evidence that the ossuary of James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus, came from this particular tomb," he said. "We have entertained the possibility that this tomb might've been the family tomb of Jesus."

And it's with regard to Jesus' family that Tabor levels his most controversial claim.

"I'm ready to let the average reader know what we scholars actually discuss. And if it's shocking, it's shocking. You don't have to accept it. Jesus had a father."

Did that mean Tabor does not believe in the Virgin Birth of Jesus?

"I don't," he said. "I think all humans have a human father."

Tabor, who studied first- and second-century Rabbinic and Greek texts, suggests a possible name for the human father of Jesus.

"They begin to call Jesus, 'bar Pantera,' son of Pantera," Tabor said. "And we even have an early Greek source. He's a philosopher named Kelsus, who seems to know a bit more about it. He says that Jesus was the son of a man named Pantera, who either was or became a Roman soldier."

The tombstone of Pantera is in Germany, says Tabor.

"Pantera is from Palestine. And he dates 62 years old when he dies ... He's on the frontier in Germany. And if you figure his date and where he was ... he's a teenager. You know, a young man maybe 19 or 20 at the time Mary becomes pregnant," Tabor said.

The suggestion that Pantera may have been the father of Jesus has been proposed before, however.

"It's not some new discovery," said Dr. Donald Carson, an expert in New Testament history from Trinity University in Illinois. "It's presented in the book as this great find that has been suppressed ... But it's been discussed and carefully weighed by centuries of scholars. There is nothing new here except the association of names that go back, at the end of the day, to reports of the enemies of Christianity from the second century. Pantera was an incredibly popular name at the time of Christ."

Twin Messiahs?

Carson argues that Tabor's views are shaped by his own materialistic philosophy, which does not allow for any supernatural or extraordinary elements -- such as a Virgin Birth.

"What Dr. Tabor has done is assumed that the whole thing cannot be," Carson said. "It is a sham and therefore the evidence has to be jiggered, it has to be selectively appealed to in order to take away the evidence of God actually doing something in space, time, history. At that point, no amount of evidence will ever convince him unless he's open to the possibility that Dr. Tabor himself is wrong ... and that God has disclosed himself in space, time and history through a man. Namely, Jesus of Nazareth."

If Tabor's book is controversial on the birth of Jesus, it also raises questions about Jesus' early ministry. Tabor suggests there were two messiahs, not one.

Tabor took "Nightline" to a second cave on our visit to Jerusalem --

this time to the East.

The Suba Cave, as it is now known, is the site of a major archaeological dig. Inside the cave are primitive, centuries-old etchings, which Tabor believes depict the life of John the Baptist. The cave also contains thousands of first-century pottery shards.

Tabor suggests that given the number of individuals, who may have been baptized in Suba, it's likely that Jesus, not John, was actually performing the baptisms.

"I like to surprise with my answers," said Tabor. "Are you ready for this? This is John's area but you know text-wise, we have no record of John baptizing here near Ein Kerem and Suba. He's up along the Jordan River in the Jordanian wilderness. The person we have a record of baptizing here is Jesus, Jesus the Baptist."

Tabor believes that, contrary to the New Testament, Jesus and John the Baptist were twin Messiahs. He says that early texts anticipated more than one Messiah and that the practice of baptism suggests that they were acting similarly in their respective ministries.

"It hit me, how this would have electrified the country," Tabor said. "You see, all these predictions of two Messiahs, and we've got two Messiahs on the ground, operating, one in the north -- John the priest -- one in the south -- Jesus the king. And they're baptizing thousands of people."

Carson, however, strongly disagrees. "Now the texts do not say they did it [baptism] at the same place at the same time. If they did, it wouldn't bother me one way or the other. In other words I don't think the Suba cave adds anything to the account in that respect ... Merely numbers of people being baptized by itself doesn't say very much about the relationship of the two men or that they were both Messiahs or anything like that."

According to Carson, John the Baptist is absolutely clear as to Jesus being the one Messiah.

"John the Baptist says that he is not worthy to even undo the sandals of Jesus," Carson said. "When Jesus asks for baptism, according to Matthew's account, John the Baptist says, 'Wait a minute, I should be baptized by you, not the other way around'. He sees himself as announcing the coming of another.

Whereas, by contrast, when Jesus talks about John there is not a sort of mutual admiration society of colleagues, still less a kind of a minor admiration for a predecessor. In other words, it is correct to say that John the Baptist does initiate the movement. But to say he is therefore the first Messiah simply goes beyond the evidence."

In addition to Tabor's claims that Jesus had an earthly father and a fellow Messiah, his book also argues it was Jesus' intention to build a dynasty on earth. Tabor says that it was Jesus' half-brother James who would inherit the title role of dynastical king after the crucifixion.

But again, Carson is adamant that the title of the book, "The Jesus Dynasty," is plain wrong.

"The dynasty bit presupposes that there is continuity. That is, there's succession. But the New Treatment evidence, such as it is, is that Jesus is the final king who goes on ruling and reigning. He doesn't need a dynasty, precisely because he is the ongoing king."

Carson insists there was no plan to build a Jesus dynasty.

"No. None," he said. "Jesus was king forever."

The book itself is bound to raise questions and arouse debate. And the argument about the historical Jesus will continue for now.

The Lost Tomb of Jesus

Claims about Jesus’ ‘lost tomb’ stir up tempest

Experts blast suggestions that his bones were found in 1980

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/17345429/

JERUSALEM - Archaeologists and clergymen in the Holy Land derided claims in a new documentary produced by James Cameron that contradict major Christian tenets, but the Oscar-winning director said the evidence was based on sound statistics.

"The Lost Tomb of Christ," which the Discovery Channel will run on March 4, argues that 10 ancient ossuaries — small caskets used to store bones — discovered in a suburb of Jerusalem in 1980 may have contained the bones of Jesus and his family, according to a press release issued by the Discovery Channel.

One of the caskets even bears the title, "Judah, son of Jesus," hinting that Jesus may have had a son. And the very fact that Jesus had an ossuary would contradict the Christian belief that he was resurrected and ascended to heaven.

Cameron told NBC'S TODAY show that statisticians found "in the range of a couple of million to one in favor of it being them." Simcha Jacobovici, the Toronto filmmaker who directed the documentary, said the implications "are huge."

"But they're not necessarily the implications people think they are. For example, some believers are going to say, well, this challenges the resurrection. I don't know why, if Jesus rose from one tomb, he couldn't have risen from the other tomb," Jacobovici told TODAY.

Goes against conventional wisdom

Most Christians believe Jesus' body spent three days at the site of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem's Old City. The burial site identified in Cameron's documentary is in a southern Jerusalem neighborhood nowhere near the church.

In 1996, when the British Broadcasting Corp. aired a short documentary on the same subject, archaeologists challenged the claims. Amos Kloner, the first archaeologist to examine the site, said the idea fails to hold up by archaeological standards but makes for profitable television.

"They just want to get money for it," Kloner said.

Cameron said his critics should withhold comment until they see his film.

"I'm not a theologist. I'm not an archaeologist. I'm a documentary filmmaker," he said.

The film's claims, however, have raised the ire of Christian leaders in the Holy Land.

"The historical, religious and archaeological evidence show that the place where Christ was buried is the Church of the Resurrection," said Attallah Hana, a Greek Orthodox clergyman in Jerusalem. The documentary, he said, "contradicts the religious principles and the historic and spiritual principles that we hold tightly to."

How possible is it?

Stephen Pfann, a biblical scholar at the University of the Holy Land in Jerusalem who was interviewed in the documentary, said the film's hypothesis holds little weight.

"I don't think that Christians are going to buy into this," Pfann said. "But skeptics, in general, would like to see something that pokes holes into the story that so many people hold dear."

"How possible is it?" Pfann said. "On a scale of one through 10 — 10 being completely possible — it's probably a one, maybe a one and a half."

Pfann is even unsure that the name "Jesus" on the caskets was read correctly. He thinks it's more likely the name "Hanun." Ancient Semitic script is notoriously difficult to decipher.

Kloner also said the filmmakers' assertions are false.

"It was an ordinary middle-class Jerusalem burial cave," Kloner said. "The names on the caskets are the most common names found among Jews at the time."

Bone-box controversy resurrected

Archaeologists also balk at the filmmaker's claim that the James Ossuary — the center of a famous antiquities fraud in Israel — might have originated from the same cave. In 2005, Israel charged five suspects with forgery in connection with the infamous bone box.

Christianity, Resurrection and The Jesus Family Tomb

Is This Jesus's Tomb?

http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1593893,00.html

There were two types of fame on display at the press conference Monday morning in a grand, sky-lit room at the back of the New York Public library. There was director James Cameron, towering like a a six-foot-plus druidic monolith in a dark jacket and black turtleneck. And there was a light tan limestone box about two feet long lying on a table in front of Cameron — which the Titanic director was presenting as the burial box of Jesus Christ. All things being equal, we know who would be the bigger draw. (It was John Lennon who said he was bigger than Jesus, not Cameron, right?) But all things were not equal. Those in the room knew that Cameron was provably authentic. The other guy? Much more problematic.

Cameron (acting as producer), biblical film documentarian Simcha Jacobovici and a handful of their expert consultants were at the Library to publicize Jacobovici's The Jesus Family Tomb, which will run this Sunday on the Discovery Channel, and a HarperSanfrancisco book of the same name. Their claim is that there was indeed a Jesus family tomb in what is now suburban Jerusalem: and that the two bone boxes on the table in front of them, exported from Israel, had contained the remains of Jesus and Mary Magdalene, whom the filmmakers assert was Jesus's wife and the mother of a son named Judah. Meet the Jesuses! Cameron told the press that when Jacobovici, who has been working on the project for years, laid it out for him in detail, he thought, "I'm not a biblical scholar, but it seemed pretty darned compelling." He added, "I said, this is the biggest achaeology story of the century. And I still believe that to be true."

If true, of course, it is more than that. If true, it is a contradiction, in the most earthy, concrete way, of the Bible, which claims that Jesus was taken up bodily into heaven.

But as its creators have revealed more and more of it over the last two days, key parts of it seem increasingly like debatable conjecture.

Here's the set-up. In 1980 a construction crew in the Jerusalem suburb of Talpiot chanced upon a first-century tomb, which are not uncommon in that city. The Israeli Antiquities Authority found 10 bone boxes there, and stored them in a warehouse. Some bore inscribed names: Jesus, son of Joseph; Maria; Mariamene e Mara; Matthew; Judas, son of Jesus; and Jose. Each name with the exception of Mariamene seemed common to their period, and it was only in 1996 that the BBC made a film suggesting that. given the combination, it might be that family. The idea was eventually discounted, however, because, as University of St. Andrews (Scotland) New Testament expert Richard Bauckham asserted in a subsequent book, the names with Biblical resonance are so common that even when you run the probabilities on the group, the odds of it being the famous Jesus's family are "very low."

Jacobovici, however, remained fascinated, and announced at the press conference what he had added to the equation:

—University of North Carolina scholar James Tabor told him that Mariamene was the name some Christians gave to Mary Magdalene. If true, that added a rather uncommon name to the statistical mix. (Or as Cameron put it, "If you found a John, a Paul and a George, you're not going to leap to any conclusions... unless you found a Ringo.").

—Jacobovici also contends that "Jose," a name that appears in the Bible as that of one of Jesus's brothers, is rarer than previous scholars thought.

— He came up with a new process called "patina fingerprinting," which purports to show that a different bone box that popped up in the hands of an Israeli collector some years ago and is alleged to have contained the remains of Jesus's brother James originally came from Talpiot, which would raise the coincidence level even higher.

—And Jacobovici managed to get tests done on DNA from the "Jesus" and "Mariamene" bone-boxes that indicated that they were not related on their mother's sides: therefore, Jacobovici quotes the DNA expert as saying, if this was indeed a family tomb, the two "would most likely have been husband and wife" (which is the source of his contention that Jesus and Mary Magdalene were married and that the Judah in the tomb was their son).

That last bit alone should give some sense of how problematic some of Jacobovici's conclusions are. A sampling of difficulties:

— If "Jesus" and "Mariamene" weren't related matrilineally, why jump to the conclusion that they were husband and wife, rather than being related through their fathers?

— The first use of "Mariamene" for Magdalene dates to a scholar who was born in 185, suggesting that Magdalene wouldn't have been called that at her death.

— St. Andrews' Bauckham defends his probabilities, noting that Jacobovici was comparing his name-cluster to the rather small sampling of names known to have been found on bone boxes, while his own basis for comparison, which adds names from contemporary literature and other sources, makes the combo far less unusual.

— Asbury Theological Seminary professor Ben Witherington, a early Christianity expert who was deeply involved with the James Ossuary, says there are physical reasons to believe it couldn't have originated in the Talpiot plot.

Darrell Bock, a professor at the conservative Protestant Dallas Seminary, whom the Discovery Channel had vet the film two weeks ago, adds another objection: why would Jesus's family or followers bury his bones in a family plot and "then turn around and preach that he had been physically raised from the dead?" If that objection smacks secular readers as relying too heavily on scripture, then Bock's larger point is still trenchant: "I told them that there were too many assumptions being claimed as discoveries, and that they were trying to connect dots that didn't belong together."

The lost tomb of Jesus" BANNED in India

Seven Historical Facts About The Resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth

http://www.newhope.bc.ca/digest11.htm

The death and resurrection of Jesus are two events in the New Testament in which Jesus is crucified and resurrected three days later (John 19:30–31, Mark 16:1, Mark 16:6). The New Testament also mentions several resurrection appearances of Jesus on different occasions to his twelve apostles and disciples, including "more than five hundred brethren at once," (1Corinthians 15:6) before Jesus' Ascension. These two events are essential doctrines of the Christian faith, and are commemorated by Christians during the liturgical times of Passiontide and Eastertide, particularly during Holy Week.

Other groups, such as Jews, Muslims and other non-Christians, as well as some liberal Christians, dispute whether Jesus actually rose from the dead; hence, arguments over death and resurrection claims occur at many religious debates and interfaith dialogues.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Death_and_Resurrection_of_Jesus

Was Jesus killed by a blood clot?

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/4075936.stm

Jesus may have died from a blood clot in his lungs, Israeli doctors believe.

Dr Benjamin Brenner from Rambam Medical Centre bases his theory on New Testament and contemporary religious sources about the crucifixion.

He believes Jesus developed a deep vein thrombosis in his legs while nailed to the cross, which then travelled from his legs to his lungs and killed him.

Other scientists dismissed the theory. Bible scholars said the spirituality behind Jesus' death was more important.

DVT

Dr Brenner looked at an in-depth study into Christ's crucifixion that had been published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 1986 by Dr William Edwards and colleagues from the US.

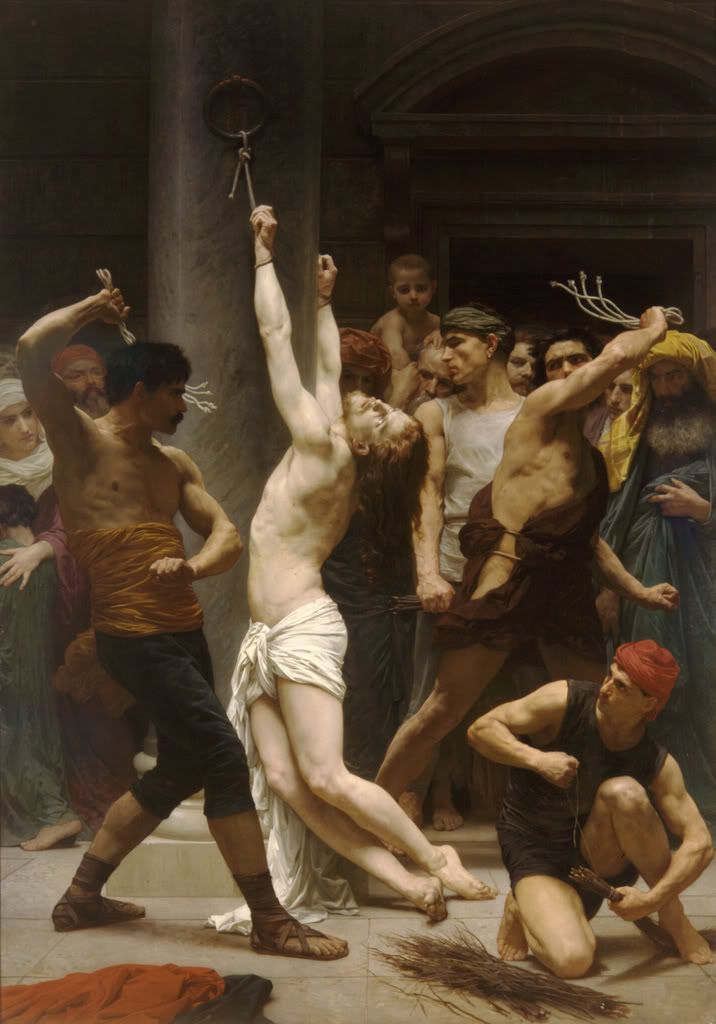

That study found that before his crucifixion, Jesus went 12 hours without food or water, was under intense emotional stress and was beaten and forced to walk to the crucifixion site carrying the heavy cross beam of the cross on which he was killed.

It is commonly believed that Jesus died from asphyxiation and blood loss after being nailed to the cross.

Dr Brenner claims that the authors may have missed the possibility of a blood clot.

Missing the point

Awareness about DVT and the associated complication of pulmonary embolism - when the blood clot reaches the lungs - has been growing in recent years, particularly in relation to immobility and long-term travel, dubbed economy class syndrome.

Jesus was on the cross for only six hours. It seems unlikely that a large DVT could develop

Dr William Edwards, author of the JAMA study

He said "It is known that the common cause of death in the setting of multiple trauma, immobilisation and dehydration is pulmonary embolism.

"This fits well with Jesus' condition and actually was in all likelihood the major cause of death of crucified victims."

He told the Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis that Jesus probably died three to six hours after the crucifixion from the clot.

But Dr Edwards dismissed Brenner's theory saying he was well aware of the effects of pulmonary embolism at the time that he wrote the Journal of the American Medical Association study.

"We didn't list it in our article because we didn't consider it a likely cause. "Jesus was on the cross for only six hours. It seems unlikely that a large DVT could develop and cause fatal pulmonary embolism in that short time."

Bible scholars said by focusing on the cause of death they were missing the point.

Stephen Pfann, a Bible scholar in Jerusalem, said: "What they are doing is an autopsy of the physical body which is always interesting from an academic standpoint.

"But if people concentrate on that part of the event alone they are missing the most important part, which is the spiritual suffering.

"The major trauma for the son of God is spiritual trauma, the loneliness feeling the rejection of God and the shame of the world that came upon him at that point."

Long-lost gospel of Judas recasts 'traitor'

http://www.usatoday.com/news/religion/2006-04-06-judas_x.htm

Lost for centuries and bound for controversy, the so-called gospel of Judas was unveiled by scholars Thursday.

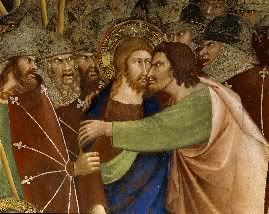

With a plot twist worthy of The Da Vinci Code, the gospel — 13 papyrus sheets bound in leather and found in a cave in Egypt — purports to relate the last days of Jesus' life, from the viewpoint of Judas, one of Jesus' first followers. Christians teach that Judas betrayed Jesus for 30 pieces of silver, but in this gospel, he is the hero, Jesus' most senior and trusted disciple and the only one who knows Jesus' true identity as the son of God.

"We're confident this is genuine ancient Christian literature," said religious scholar Bart Ehrman of the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. He and others on the translation team spoke at a National Geographic Society briefing, where they released a translation.

The manuscript claims that Jesus revealed "secret knowledge" to Judas and instructed him to turn Jesus over to Roman authorities, said Coptic studies scholar Stephen Emmel of Germany's University of Munster, one of the restoration team members. In the gospel text, Judas is given private instruction by Jesus and is granted a vision of the divine that is denied to other disciples, who do not know that Jesus has requested his own betrayal. Rather than acting out of greed or malice, Judas is following orders when he leads soldiers to Jesus, the gospel says.

Other theologians, biblical scholars and pastors say this contrary text is not truly "good news" (the meaning of "gospel") and will make no difference to believers as Easter approaches. The Bible, they say, is a closed book, nearly universally accepted as the official church teachings since the fourth century.

"Just because you can date a document to early Christian times doesn't make it theologically true," said Pastor Rod Loy of the First Assembly of God in North Little Rock "Do you decide everything you read on the Internet is true because it was written on April 6, 2006? Fiction has been around for as long as man."

Found by a farmer

Radioactive-carbon-dating tests and experts in ancient languages establish that the document was written between A.D. 300 and 400, the team said. Written in Coptic, an old Egyptian language, the gospel was unearthed by a farmer in a "tomb-like box" in 1978, said Terry Garcia of the National Geographic Society. It is part of a codex, or collection of devotional texts, found in a cave near El Minya, Egypt.

The farmer sold the codex to an antiquities dealer in Cairo, without alerting Egyptian antiquities officials. In a secret showing in 1983, the antiquities dealer, unaware of the content of the codex, offered the gospel for sale to Emmel and another scholar in a Geneva, Switzerland hotel room.

Given a hurried half-hour to examine the codex, Emmel first suspected the papyrus sheets discussed Judas, he said, based on a hasty glimpse of the text, which was littered with references to the disciple in Coptic. But the asking price was too exorbitant, as high as $3 million, Garcia said.

For the next 16 years, the document moldered in a Hicksville, N.Y., bank safe-deposit box, deteriorating until Zurich-based antiquities dealer Frieda Nussberger-Tchacos purchased it in 2000, alarmed at its fragmentation, Garcia said. National Geographic said it did not know the purchase price.

In 2001, the codex was acquired by the Maecenas Foundation for Ancient Art in Switzerland, Garcia said. The foundation invited National Geographic to help with the restoration in 2004 and also reached an agreement with the Egyptian government to return it after its restoration.

Restoration of the thousands of papyrus fragments has made 80% of the gospel legible. The National Geographic Society learned of the find 2½ years ago, Garcia said. The society recruited the scholarly restoration team and got a $1 million grant from the Waitt Foundation for Historical Studies.

The gospel "is an intriguing alternative view of the relationship between Jesus and Judas," Emmel said. It also has Jesus relating a new creation myth and account of humankind's origins to Judas, which suggest God didn't create the world, contrary to conventional Christian belief.

The key passage has Jesus telling Judas "'you will exceed all of them. For you will sacrifice the man that clothes me,'" Emmel said. The passage reflects the view that material things and the body are traps for the inner soul and also suggests a form of mysticism found in some early Jewish thought, said team adviser Marvin Meyer of Chapman University in Orange, Calif.

The Judas gospel is probably a copy of a heretical text denounced by a Christian bishop around A.D. 180, Emmel said. But other scholars, such as Michael Penn of Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Mass., say there is no way to be certain it is the same text, given the plethora of devotional texts that were floating around among early Christians.

The Judas papyrus is one of dozens of gospels found in recent decades whose texts fall outside the canon of today's New Testament Bibles. The canon was largely set at the Synod of Rome in 382 when the dominant Christian leaders of the time established the authority of the gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John as the accepted version of Jesus' birth, life, crucifixion and resurrection.

Scripture, like history, was codified by the winners, by those who emerged with the greatest numbers at the end of three centuries of Christianity, said Michael White, director of the Institute for the Study of Antiquity and Christian Origins at the University of Texas-Austin, He has counted more than three dozen gospels that didn't make the canonical cut. The ones that did, he said, were not in total harmony but shared a theological view of the passion, the crucifixion and their significance that became the core of the new religion.

"In the ancient world, Christianity was even more diverse than it was today," Ehrman said. Not until later centuries did the standard devotional texts known as the New Testament become the bedrock of the Christian faith. Dozens of alternative gospels and creeds lost out in the process.

"I suspect the gospel of Judas was not one of the close calls in this process," said Penn, who was not on the National Geographic team.

The gospel of Judas is broadly representative of "gnostic" beliefs prevalent in the two or three centuries after the death of Jesus, said the Rev. Donald Senior of the Catholic Theological Union in Chicago, who was an adviser to the restoration team.

Gnostic beliefs hold that secret and personal insights are the key to redemption, rather than faith in Jesus' resurrection, for example. Rather than shedding a new light on Judas' relationship to Jesus, Senior suggested, the gospel illuminates the diversity of thought among early Christians.

And as for Judas' supposed betrayal?

Craig Hill, professor of New Testament at Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington, D.C., would let the villain off history's hook, papyrus or not.

"What Jesus did — raising crowds and civic unrest — would have gotten him killed anywhere in the Roman Empire," Hill said.

National Geographic is banking on the new gospel to capture the modern imagination. It plans to feature the gospel in its magazine, books and TV special this Sunday (National Geographic Channel, 8 p.m. ET/9 PT). The Maecenas Foundation will give the manuscript to Egypt's Coptic Museum after the restoration is complete, Garcia said.

'No bearing' on the Easter story

The Judas gospel has "no bearing whatsoever on (the Easter) story, much less on the faith of the Christian church," said the Rev. Albert Mohler Jr., president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville. He dismissed the gospel of Judas as nothing more than "an ancient manuscript that tells an interesting story."

No scholar has called the gospel a forgery. But one concern, Penn said, is that it was purchased from an antiquities dealer rather than discovered by an archaeological team.

Scholars fear that such purchases will drive further looting of archaeological sites.

Coptic scholar Rodolphe Kasser of the University of Geneva, who headed the restoration team, said the priority for scholars was saving the gospel before it deteriorated completely.

Tests of the gospel included radiocarbon dating conducted at the University of Arizona, and chemical analysis of the papyrus and ink used in the codex as well as its leather binding. Restoration involved computer and hand patching of the document to reassemble its pages.

"The publication team appears to have done everything possible to authenticate the gospel as an ancient work," said religious scholar Mark Chancey of Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

"There seems to be little doubt that it is, indeed, a late third- or early fourth-century work, and not a modern forgery."

Princeton University religious scholar Elaine Pagels, a restoration adviser best known for her work on the Nag Hammadi texts, said, "The gospel of Judas is an astonishing discovery that along with dozens of similar texts have in recent years have transformed our understanding of early Christianity."

She compared it to other gnostic works, such as the gospels of Thomas and of Mary Magdalene, denounced as heretical by the early church but "loved and copied and circulated by people who thought of themselves as Christians."

Many similar "apocryphal" gospels are attributed to important figures in early Christianity, Chancey said, though most scholars doubt that they were actually written by their purported authors.

"It is clear, for example, that Judas did not write this work," Chancey said. The gospel clearly reflects second-century developments, long after Judas, he said.

Experts do see some value in a Bible news flash that prompts modern believers to re-examine the character of Judas.

The Rev. James Martin, associate editor of the Jesuit magazine America, spent months last year as the theological consultant on an off-Broadway play, The Last Days of Judas Iscariot. The script had Judas on trial and concluded that he went to hell as much for his suicidal despair as for betraying Jesus.

"He chose damnation rather than accepting God's forgiveness, and that is our fate if we are so proud we think our sins are beyond God's reach," said Martin.

Meyer noted that Judas has often been used by Christians to attack Jews throughout history.

"The view of Judas as this evil Jewish person who turned Jesus in fed the flames of anti-Semitism," he said, so providing a new view of Judas may help counteract such views.

The last days of Jesus

Scholars explore history behind famous story

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/4315203/

For 5,000 years, the city of Jerusalem has stood witness to the rise and fall of civilizations, the birth of great religions and the death of a man who changed the world: Jesus of Nazareth. Gospel accounts of his crucifixion are the inspiration for Mel Gibson's new film, "The Passion of the Christ." Scheduled for release on Feb. 26, the film has already sparked enormous controversy for how it portrays Jesus' death.

DATELINE NBC

To purchase a VHS copy of this show, please call 1-866-NBC-TAPE.

For some there is no controversy, the gospels are literal truth. For others, what happened isn't so clear. So, we decided to seek out some of the world's most respected scholars -- believers and non-believers -- to find out what they think happened almost 2,000 years ago. We're not exploring the mysteries of faith, but the mysteries of history, to piece together the last days and moments of Jesus' life.

Piecing together what happened that week is a task that has puzzled scholars for centuries. The evidence is scarce, with different and sometimes contradictory books of the Christian gospel and a few lines penned by ancient historians. So what forces triggered Jesus’ death? Who was ultimately responsible? Our search begins five days before the crucifixion, on a Sunday in about the year 30, when the gospels say Jesus traveled to Jerusalem for the festival of Passover.

Paula Fredriksen, Aurelio Professor of Scripture, Boston University: “One of the lovely things about the gospel stories of Jesus' entry to Jerusalem for his last Passover is the tradition of the triumphal entry. Jesus is danced into the city by pilgrims that are singing about the coming kingdom of God.”

It's impossible to know how many pilgrims turned out that day -- but when Jesus entered the city, the gospels say he received a hero's welcome -- a kind of ancient ticker-tape parade:

Craig A. Evans, Professor of New Testament, Acadia Divinity College: “I see people lining the roadway leading into Jerusalem. They're waving the branches - showing that they believe in Jesus. He's smarter than the scribes. And he's the greatest. And so they're all excited.”

Jesus was a Jewish preacher from a small town in rural Galilee, an area some say was known for its political activism. And for at least a year, the gospels say, he'd been traveling the countryside, reaching out to the common people, including the outcasts, the unpopular and downtrodden of his time.

Evans: “He had this power and this charisma about him that had never been seen or experienced before.”

Stone Phillips: “How big was his following?”

Evans: “Well, we don't know for sure. Certainly hundreds at any given time in his ministry and public activities. He was a phenomenon.”

Scholars believe that crowds were drawn by reports of miraculous healings -- and that many came to see him as the long-promised savior who would usher in something called the Kingdom of God.

Evans: “They think he's the Lord's savior for the Jewish people. Jesus proclaimed the kingdom of God, and by that he meant the powerful presence of and rule of God.”

Today, most Christians tend to think of that kingdom as a kind of spiritual or heavenly realm, but scholars say that that a 1st Century Jew like Jesus may have had something far more worldly in mind.