File sharing is the practice of making files available for other users to download over the Internet and smaller networks. Usually file sharing follows the peer-to-peer (P2P) model, where the files are stored on and served by personal computers of the users. Most people who engage in file sharing are also downloading files that other users share. Sometimes these two activities are linked together. P2P file sharing is distinct from file trading in that downloading files from a P2P network does not require uploading, although some networks either provide incentives for uploading such as credits or force the sharing of files being currently downloaded.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File_sharing

Interest in File-Sharing at All Time High

http://www.slyck.com/news.php?story=763

RIAA File-Sharing Lawsuits Top 10,000 People Sued

http://yro.slashdot.org/article.pl?sid=05/04/30/1913227&from=rss

The RIAA vs. John Doe, a layperson's guide to filesharing lawsuits

http://digitalmusic.weblogsinc.com/2006/08/07/the-riaa-vs-john-doe-a-laypersons-guide-to-filesharing-lawsui/

File sharing timeline

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File_sharing_timeline

Comparison of file sharing applications

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparison_of_file_sharing_applications

Sharing for Dummies

http://www.slyck.com/story1550_Sharing_for_Dummies

The term P2P refers to "peer-to-peer" networking. A peer-to-peer network allows computer hardware and software to function without the need for special server devices. P2P is an alternative to client-server network design.

P2P is a popular technology for file sharing software applications like Kazaa, WinMX and Overnet. P2P technology helps the P2P client applications upload and download files over the P2P network services.

P2P technology can also be found in other places. Microsoft Windows XP (starting with Service Pack 1), for example, contains a component called "Windows Peer-to-Peer Networking." P2P is especially popular in homes where an expensive, decidated server computer is neither necessary nor practical.

Finally, the P2P acronym has acquired a non-technical meaning as well. Some people have described this second meaning of "P2P" as "people-to-people." From this perspective, P2P is a model for developing software and growing businesses that help individuals on the Internet meet each other and share common interests. So-called social networking technology is an example of this concept.

http://compnetworking.about.com/od/p2ppeertopeer/g/bldef_p2p.htm

P2P File Sharing

Napster was a file sharing service that paved the way for decentralized P2P file-sharing programs such as Kazaa, Limewire, iMesh, and BearShare, which are now used for many of the same reasons and can download music, pictures, and other files. The popularity and repercussions of the first Napster have made it a legendary icon in the computer and entertainment fields.

Napster's brand and logo continue to be used by a pay service, having been acquired by Roxio.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napster

Napster Testimonies

Napster: Then and Now

http://iml.jou.ufl.edu/projects/Spring01/Burkhalter/Napster%20history.html

In 1999, an 18-year-old college dropout named Shawn Fanning changed the music industry forever with his file-sharing program called Napster. His idea was simple: a program that allowed computer users to share and swap files, specifically music, through a centralized file server. His response to the complaints of the difficulty to finding and downloading music over the Net was to stay awake 60 straight hours writing the source code for a program that combined a music-search function with a file-sharing system and, to facilitate communication, instant messaging. Now we have Napster, and people are pissed.

A Brief History of Filesharing: From Napster to Legal Music Downloads

The Birth and Ascent of the (in)famous Peer-to-peer Revolution

http://www.associatedcontent.com/article/20644/a_brief_history_of_filesharing_from.html

Back in the good ol' days when music was a commodity purveyed by those privileged members of the recording industry elite, CDs were expensive and cumbersome, but basically unavoidable. Lacking both the sentimentality of vinyl records and the affordability of cassette tapes, they were often packaged with a generous amount of "filler" songs to pad the one or two marketable singles, and seemed to have no distinct advantages, save one: each track was an exact, digital replica of the original. In the years before the advent of broadband connections and mammoth hard drives, this advantage went relatively unnoticed. But as online technology improved and it became easier to transfer large amounts of data via the Internet, enterprising individuals discovered that CDs, as a digital media form, were tailor-made for the wired world.

Suddenly that "revolution" the Beatles had sung of decades earlier seemed closer at hand than anyone had expected. It came with the explosion of peer-to-peer (or P2P) applications which allowed listeners, for the first time, to exercise their own control over what songs were and were not worth paying for. And it came not with a whimper, but a really loud bang.

Enter Napster, stage left. Cobbled together by a scruffy-haired high school dropout named Shawn Fanning in the summer of 1999, the open-source software was originally intended as a clandestine experiment among 30 or so of his friends, but word of mouth proved stronger than secrecy, and by the end of its first week Napster had been downloaded by as many as 15,000 users. Characterized by the now-legendary Alien With Headphones logo, the program allowed users to swap media files - specifically music tracks - via a centralized server.

It was that centralization that led to its eventual downfall. Unlike the many subsequent programs which circumvented the need for a main server (and thus made their services essentially anonymous), Napster's cohesive nature made it vulnerable to the legal attacks that began almost immediately upon its inception. Starting in 2000, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) spearheaded a series of lawsuits aimed at shutting down Fanning and Co. Their legal ground seemed unshakeable, their argument unquestionable: facilitating the free trade of "illicit" music files amounted to a violation of copyright law. In fact, at Napster's peak in February 2001, it amounted to over 2.79 billion violations, the approximate number of files traded during that month.

By then the RIAA had whipped itself into a foaming-at-the-mouth frenzy, issuing statements like those by Ron Stone of Gold Mountain Management, who described Napster as "the single most insidious Web site I've ever seen." Their line of reasoning soon diverged into two distinct schools of thought: the polarizing assertion that music filesharing is stealing - and therefore morally wrong - and the more pragmatic allegation that P2P software directly affects CD sales. Six years after Napster's untimely demise...felled by a court injunction in July of 2000, its end was mourned with the equivalent fervor of a royal funeral...peer-to-peer programs have grown steadily, mounting opposition notwithstanding, in their variety and quality. But the charges leveled against them and their users remain essentially the same.

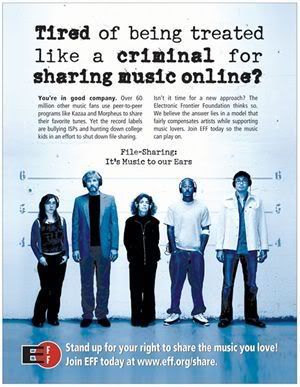

Increasingly, however, critics of the RIAA's war on filesharing are speaking out against these previously undisputed claims. Big-name artists like Metallica and Dr. Dre have been the vanguard of the recording industry's army, raising hell in the name of "copyright protection" and painting the legions of filesharers as common thieves. But in the midst of the firestorm, countless other bands have been quietly benefiting from the increased exposure that P2P programs provided, and despite legal setbacks, filesharing has inevitably fallen into its natural role as the next big publicity tool.

Capitalizing on the Internet's anonymity and its tendency to facilitate the exchange of ideas and art forms, bands as prolific as the über-popular Linkin Park are using the online community in a homegrown PR effort to generate enthusiasm for their music and live shows. In early 2000 a demo version of their track "Plaster" showed up on the website of StreetWise Concepts (a promotional company), and quickly made its way to the P2P networks. Online word of mouth almost singlehandedly catapulted the Californian outfit from semi-obscurity to Total Request Live, in the space of a little under a year. And in other corners of the music world, independent artists are banding together in support of the universal self-direction that peer-to-peer networks promote. One such group is the experimental, anti-pop outfit Negativland, who released a statement in 2002 supporting the creators of Morpheus, the heir apparent to the Napster throne. "We encourage and promote the free exchange of our own music on the Internet using file sharing programs and P2P networks," they declared in its opening paragraphs. "We consider this new opportunity to share our music and ideas with others, and for others to share our music and ideas with each other, to be good for us, good for society, and good for art."

This previously-taboo concept of filesharing as a means of contributing to the richness of the independent music scene struck at the heart of the RIAA's debate. Suddenly listeners...and, in growing numbers, the artists themselves...were unwilling to accept the unspoken rule that music must be thought of in terms of buyer/seller relationships, in terms of intellectual property exchanging hands, in terms of transactions.

Mark Holser, one third of Negativland, points to the inherently interactive nature of the Internet as the means by which this paradigm shift occurred. With the advent of P2P networks came the erosion of the concept of music-as-property, giving listeners an unprecedented role in the production and distribution of new and innovative forms of expression. He explains its infectious power in terms of "personal contribution rather than anonymous absorption…and it does this without a profit-making center of control or executive offices making decisions about its future. The difference consists of who and what is really in charge, and who and what it's really all for."

Indeed, for all the volume and reiteration of the recording industry's intensely-moralistic claim that filesharing is "both wrong and illegal" (the oft-repeated slogan of RIAA president Cary Sherman), it falls somewhat flat among a markedly more skeptical target audience, an audience which has begun to suspect that perhaps the five major labels comprising the Association - BMI, Sony, Warner, EMI and Universal - might not, in fact, have the issue of artistic integrity at the top of their list of priorities. And though the industry has jumped, albeit belatedly, on the digital bandwagon with the introduction of "legitimate" services like iTunes, these concessions to the downloading public fail spectacularly to compete with the sheer diversity of artists and styles that can be found on even the smaller P2P networks like Limewire or BearShare. Such failures only serve to reinforce the popular notion that the recording industry, at its core, seems shamefully misguided, and utterly incapable of originality.

And as the moral column of the RIAA's two-tiered platform begins to crumble, its economic counterpart is already well on its way. Assertions by the industry that an increase in filesharing correlates directly with a negative downturn in commercial profits were previously accepted as fact, despite a notable lack of dependable statistical data and an overreliance on circumstantial evidence. But in a recent report published by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, economists Felix Oberholzer-Gee and Koleman S. Strumpf deconstruct the RIAA's standby argument that an increase in filesharing translates to a decrease in CD sales, with a first-of-its-kind study that directly observes the relationship between the two factors. "Downloads have an effect on sales which is statistically indistinguishable from zero, despite rather precise estimates," they note in the report, pointing out that many downloaded files are songs which the majority of users would not have paid for even if P2P programs did not exist at all.

In addition to being questionably motivated, the industry's effort to unilaterally eradicate peer-to-peer software occasionally seems to border on the self-destructive: many experts feel that, by relying on such reactionary tactics, the RIAA has simply shot itself in the foot. Nicholas Economides, a professor at New York University's Stern School of Business, believes that their rashness will only eliminate their chances of profiting in the long-run from the P2P technology which is, quite evidently, here to stay. "Consumers will go to these alternative public domain programs and the record industry will end up getting nothing out of it," he predicts. "With Napster, they might at least have struck a deal so that the labels could have made money on it."

And nearly half a decade after the first ripples of filesharing spread throughout the online community, the industry still remains ostensibly poised with the gun pointed straight at their expensive calfskin loafers. But the filesharing public remains unswayed, and in the face of corporate swagger, they merely shrug. It's a gesture that's succinctly expressive of the collective opinion articulated in Michael Gowan's paean to free music, Requiem for Napster: "You guys worry about the money. We'll enjoy the music. Copyrights are for squares, man."

A peer-to-peer (or "P2P") computer network relies primarily on the computing power and bandwidth of the participants in the network rather than concentrating it in a relatively low number of servers. Peer-to-peer networks are typically used for connecting nodes via largely ad hoc connections. Such networks are useful for many purposes. Sharing content files (see file sharing) containing audio, video, data or anything in digital format is very common, and realtime data, such as telephony traffic, is also passed using P2P technology.

A pure peer-to-peer network does not have the notion of clients or servers, but only equal peer nodes that simultaneously function as both "clients" and "servers" to the other nodes on the network. This model of network arrangement differs from the client-server model where communication is usually to and from a central server. A typical example for a non peer-to-peer file transfer is an FTP server where the client and server programs are quite distinct, and the clients initiate the download/uploads and the servers react to and satisfy these requests.

The earliest peer-to-peer network in widespread use was the Usenet news server system, in which peers communicated with one another to propagate Usenet news articles over the entire Usenet network. Particularly in the earlier days of Usenet, UUCP was used to extend even beyond the Internet. However, the news server system also acted in a client-server form when individual users accessed a local news server to read and post articles. The same consideration applies to SMTP email in the sense that the core email relaying network of Mail transfer agents is a peer-to-peer network while the periphery of Mail user agents and their direct connections is client server.

Some networks and channels such as Napster, OpenNAP and IRC server channels use a client-server structure for some tasks (e.g. searching) and a peer-to-peer structure for others. Networks such as Gnutella or Freenet use a peer-to-peer structure for all purposes, and are sometimes referred to as true peer-to-peer networks, although Gnutella is greatly facilitated by directory servers that inform peers of the network addresses of other peers.

Peer-to-peer architecture embodies one of the key technical concepts of the internet, described in the first internet Request for Comments, RFC 1, "Host Software" dated 7 April 1969. More recently, the concept has achieved recognition in the general public in the context of the absence of central indexing servers in architectures used for exchanging multimedia files.

The concept of peer to peer is increasingly evolving to an expanded usage as the relational dynamic active in distributed networks, i.e. not just computer to computer, but human to human. Yochai Benkler has coined the term "commons-based peer production" to denote collaborative projects such as free software. Associated with peer production are the concept of peer governance (referring to the manner in which peer production projects are managed) and peer property (referring to the new type of licenses which recognize individual authorship but not exclusive property rights, such as the GNU General Public License and the Creative Commons License).

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peer-to-peer

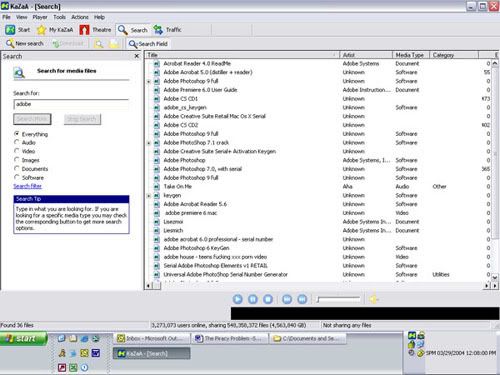

Kazaa

Kazaa Media Desktop (once capitalized as "KaZaA", but now usually left as "Kazaa") is a peer-to-peer file sharing application using the FastTrack protocol. Kazaa is owned by Sharman Networks and is infamous for the alleged high number of computer viruses, trojans and worms it helped to propagate.

Kazaa is commonly used to exchange MP3 music files over the Internet. However it can also be used to exchange other file types, such as videos, applications, and documents. The official Kazaa client can be downloaded free of charge, bundled with adware and spyware, although there are "No spyware" claims found on Kazaa's website. Throughout the past few years, Kazaa's developing company has been the target of many copyright-related lawsuits.

WinMX

WinMX is a freeware peer-to-peer file sharing program authored by Frontcode Technologies that runs on Microsoft Windows operating systems created in 2001. Officially, the support of WinMX by Frontcode ended in 2005 when they received threats of legal action by the RIAA. While the official website and servers for WinMX have been removed, a community of developers have brought the service online independently with the use of third party patches or a simple edited host file.

BearShare

BearShare is a peer-to-peer file sharing application originally created by Free Peers, Inc. for Microsoft Windows and currently sold by MusicLab, LLC.

LimeWire

LimeWire is a peer-to-peer file sharing client for the Java Platform, which uses the Gnutella network to locate and transfer files. Released under the GNU General Public License, Limewire is free software. It also encourages the user to pay a fee, which will then give the user access to LimeWire Pro.

BitTorrent

BitTorrent is a peer-to-peer file sharing (P2P) communications protocol. BitTorrent is a method of distributing large amounts of data widely without the original distributor incurring the entire costs of hardware, hosting and bandwidth resources. Instead, when data is distributed using the BitTorrent protocol, recipients each supply data to newer recipients, reducing the cost and burden on any given individual source, providing redundancy against system problems, and reducing dependence upon the original distributor.

The protocol was designed in April 2001, implemented and first released 2 July 2001 by programmer Bram Cohen, and is now maintained by BitTorrent, Inc.[1]

Usage of the protocol accounts for significant traffic on the Internet, but the precise amount has proven difficult to measure.

There are numerous compatible BitTorrent clients, written in a variety of programming languages, and running on a variety of computing platforms.

BitComet

BitComet (originally named SimpleBT client from versions 0.11 to 0.37) is a BitTorrent client written in C++ for Microsoft Windows and available in 43 different languages. The current preview release of BitComet comes bundled with the BitComet FLV Player. It's first public release was Version 0.28. Today's BitComet logo was used since Version 0.50.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BitComet

Bram Cohen (born 1975) is an American computer programmer, best known as the author of the peer-to-peer (P2P) protocol BitTorrent, as well as the first file sharing program to use the protocol. He is also the co-founder of CodeCon, organizer of the San Francisco Bay Area P2P-hackers meeting, and the co-author of Codeville.

He currently lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with his wife Jenna and their two children.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bram_Cohen

The BitTorrent Effect

http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/13.01/bittorrent.html

"That was a bad move," Bram Cohen tells me. We're huddled over a table in his Bellevue, Washington, house playing a board game called Amazons. Cohen picked it up two weeks ago and has already mastered it. The 29-year-old programmer consumes logic puzzles at the same rate most of us buy magazines. Behind his desk he keeps an enormous plastic bin filled with dozens of Rubik's Cube-style twisting gewgaws that he periodically scrambles and solves throughout the day. Cohen says he loves Amazons, a cross between chess and the Japanese game Go, because it is pure strategy. Players take turns dropping more and more tokens on a grid, trying to box in their opponent. As I ponder my next move, Cohen studies the board, his jet-black hair hanging in front of his face, and tells me his philosophy of the perfect game."The best strategy games are the ones where you put a piece down and it stays there for the whole game," he explains. "You say, OK, I'm staking out this area. But you can't always figure out if that's going to work for you or against you. You just have to wait and see. You might be right, might be wrong." It's only later, when I look over these words in my notes, that I realize he could just as easily be talking about his life.

Bram Cohen is the creator of BitTorrent, one of the most successful peer-to-peer programs ever. BitTorrent lets users quickly upload and download enormous amounts of data, files that are hundreds or thousands of times bigger than a single MP3. Analysts at CacheLogic, an Internet-traffic analysis firm in Cambridge, England, report that BitTorrent traffic accounts for more than one-third of all data sent across the Internet. Cohen showed his code to the world at a hacker conference in 2002, as a free, open source project aimed at geeks who need a cheap way to swap Linux software online. But the real audience turns out to be TV and movie fanatics. It takes hours to download a ripped episode of Alias or Monk off Kazaa, but BitTorrent can do it in minutes. As a result, more than 20 million people have downloaded the BitTorrent application. If any one of them misses their favorite TV show, no worries. Surely someone has posted it as a "torrent." As for movies, if you can find it at Blockbuster, you can probably find it online somewhere - and use BitTorrent to suck it down.

With so much illegal traffic, it's no surprise that a clampdown has started: In November, the Motion Picture Association of America began suing downloaders of movies, in order to, as the MPAA's antipiracy chief John Malcolm put it, "avoid the fate of the music industry."

For Cohen, it's all a little surreal. He gets up in the morning, helps his wife feed their children, and then sits down at his cord-and-computer-choked desk to watch his PayPal account fill up with donations from grateful BitTorrent users - enough to support his family. Then he goes online to see how many more people have downloaded the program: At this rate, it'll be 40 million by 2006.

"I can't even imagine a crowd that big. I try not to think about it," he admits.

So he does what he always does. He narrows his focus to zoom in on the next thorny problem, the next interesting technical challenge. Like our game of Amazons.

He lays down another piece: "I think I've won now."

Like many geeks in the '90s, Cohen coded for a parade of dotcoms that went bust without a product ever seeing daylight. He decided his next project would be something he wrote for himself in his own way, and gave away free. "You get so tired of having your work die," he says. "I just wanted to make something that people would actually use."

Cohen was always interested in file-sharing. His last job was with MojoNation, a project based in Mountain View, California, that tried to create a "distributed data haven." A MojoNation user who wanted to keep a file safe from prying eyes could break it into chunks, encrypt the pieces, and store them on the millions of computers belonging to people who, theoretically, would be running the software worldwide. Too complicated for easy use, it expired like the other startups Cohen was part of. But it gave him an idea: Breaking a big file into tiny pieces might be a terrific way to swap it online.

The problem with P2P file-sharing networks like Kazaa, he reasoned, is that uploading and downloading do not happen at equal speeds. Broadband providers allow their users to download at superfast rates, but let them upload only very slowly, creating a bottleneck: If two peers try to swap a compressed copy of Meet the Fokkers - say, 700 megs - the recipient will receive at a speedy 1.5 megs a second, but the sender will be uploading at maybe one-tenth of that rate. Thus, one-to-one swapping online is inherently inefficient. It's fine for MP3s but doesn't work for huge files.

Cohen realized that chopping up a file and handing out the pieces to several uploaders would really speed things up. He sketched out a protocol: To download that copy of Meet the Fokkers, a user's computer sniffs around for others online who have pieces of the movie. Then it downloads a chunk from several of them simultaneously. Many hands make light work, so the file arrives dozens of times faster than normal.

Paradoxically, BitTorrent's architecture means that the more popular the file is the faster it downloads - because more people are pitching in. Better yet, it's a virtuous cycle. Users download and share at the same time; as soon as someone receives even a single piece of Fokkers, his computer immediately begins offering it to others. The more files you're willing to share, the faster any individual torrent downloads to your computer. This prevents people from leeching, a classic P2P problem in which too many people download files and refuse to upload, creating a drain on the system. "Give and ye shall receive" became Cohen's motto, which he printed on T-shirts and sold to supporters.

In April 2001, Cohen quit his job at MojoNation and entered what he calls his "starving artist" period. He lived off his meager savings and stayed home to work on the software all day. His pals were skeptical. "No one knew if BitTorrent would work. Everyone knew that Bram was smart, but let's face it, a lot of stuff like this fails," says Danny O'Brien, a consultant and the editor of the tech newsletter Need To Know.

What kept Cohen going, say friends and family, was a cartoonishly inflated ego. "I can come off as pretty arrogant, but it's because I know I'm right," he laughs. "I'm very, very good at writing protocols. I've accomplished more working on my own than I ever did as part of a team." While we're having lunch, his wife, Jenna, tells me about the time they were watching Amadeus, where Mozart writes his music so rapidly and perfectly it appears to have been dictated by God. Cohen decided he was kind of like that. Like Mozart? Bram and Jenna nod.

"Bram will just pace around the house all day long, back and forth, in and out of the kitchen. Then he'll suddenly go to his computer and the code just comes pouring out. And you can see by the lines on the screen that it's clean," Jenna says. "It's clean code." She pats her husband affectionately on the head: "My sweet little autistic nerd boy." (Cohen in fact has Asperger's syndrome, a condition on the mild end of the autism spectrum that gives him almost superhuman powers of concentration but can make it difficult for him to relate to other people.)

For the program's first successful public trial, Cohen collected a batch of free porn and used it to lure beta testers. (The gambit worked, as did the code.) He started releasing beta versions of BitTorrent in summer 2001. Linux geeks took to it immediately and began swapping their enormous programs. In 2004, TV-show and movie pirates began showing up on BitTorrent blogs that, like samizdat TV Guides, pointed to long lists of pirated content.

The one person who hasn't joined the plundering is Cohen himself. He says he has never downloaded a single pirated file using BitTorrent. Why? He suspects the MPAA would love to make a legal example of him, and he doesn't want to give them an opening. He's the perfect candidate for downloading, though, since he doesn't care if he sees TV live, doesn't subscribe to basic cable, and already sits at a computer all day long. The only shows he watches are those he buys on DVD. He particularly loved the first season of Paris Hilton's The Simple Life. "You can watch that show for six hours," Cohen says, "and your brain is still empty."

We wander into his garage, where he hops onto a skateboard and begins zipping back and forth. I ask him if he would download television shows if he weren't BitTorrent's creator.

He pauses for a second. "I don't know," he says. "There's upholding the principle. And there's being the only knucklehead left who's upholding the principle."

You could think of BitTorrent as Napster redux - another rumble in the endless copyright wars. But BitTorrent is something deeper and more subtle. It's a technology that is changing the landscape of broadcast media.

"All hell's about to break loose," says Brad Burnham, a venture capitalist with Union Square Ventures in Manhattan, which studies the impact of new technology on traditional media. BitTorrent does not require the wires or airwaves that the cable and network giants have spent billions constructing and buying. And it pounds the final nail into the coffin of must-see, appointment television. BitTorrent transforms the Internet into the world's largest TiVo.

One example of how the world has already changed: Gary Lerhaupt, a graduate student in computer science at Stanford, became fascinated with Outfoxed, the documentary critical of Fox News, and thought more people should see it. So he convinced the film's producer to let him put a chunk of it on his Web site for free, as a 500-Mbyte torrent. Within two months, nearly 1,500 people downloaded it. That's almost 750 gigs of traffic, a heck of a wallop. But to get the ball rolling, Lerhaupt's site needed to serve up only 5 gigs. After that, the peers took over and hosted it themselves. His bill for that bandwidth? $4. There are drinks at Starbucks that cost more. "It's amazing - I'm a movie distributor," he says. "If I had my own content, I'd be a TV station."

During the last century, movie and TV companies had to be massive to afford distribution. Those economies of scale aren't needed anymore. Will the future of broadcasting need networks, or even channels?

"Blogs reduced the newspaper to the post. In TV, it'll go from the network to the show," says Jeff Jarvis, president of the Internet strategy company Advance.net and founder of Entertainment Weekly. (Advance.net is owned by Advance Magazine Group, which also owns Wired's parent company, Cond� Nast.) Burnham goes one step further. He thinks TV-viewing habits are becoming even more atomized. People won't watch entire shows; they'll just watch the parts they care about.

Evidence that Burnham's prediction is coming true came a few weeks before the US presidential election in November, when Jon Stewart - host of Comedy Central's irreverent The Daily Show - made a now-famous appearance on CNN's Crossfire. Stewart attacked the hosts, Paul Begala and Tucker Carlson, calling them political puppets. "What you do is partisan hackery," he said, just before he called Carlson "a dick." Amusing enough, but what happened next was more remarkable. Delighted fans immediately ripped the segment and posted it online as a torrent. Word of Stewart's smackdown spread rapidly through the blogs, and within a day at least 4,000 servers were hosting the clip. One host reported having, at any given time, more than a hundred peers swapping and downloading the file. No one knows exactly how many people got the clip through BitTorrent, but this kind of traffic on the very first day suggests a number in the hundreds of thousands - and probably much higher. Another 2.3 million people streamed it from iFilm.com over the next few weeks. By contrast, CNN's audience for Crossfire was only 867,000. Three times as many people saw Stewart's appearance online as on CNN itself.

If enough people start getting their TV online, it will drastically change the nature of the medium. Normally, the buzz for a show builds gradually; it takes a few weeks or even a whole season for a loyal viewership to lock in. But in a BitTorrented broadcast world, things are more volatile. Once a show becomes slightly popular - or once it has a handful of well-connected proselytizers - multiplier effects will take over, and it could become insanely popular overnight. The pass-around effect of blogs, email, and RSS creates a roving, instant audience for a hot show or segment. The whole concept of must-see TV changes from being something you stop and watch every Thursday to something you gotta check out right now, dude. Just click here.

What exactly would a next-generation broadcaster look like? The VCs at Union Square Ventures don't know, though they'd love to invest in one. They suspect the network of the future will resemble Yahoo! or Amazon.com - an aggregator that finds shows, distributes them in P2P video torrents, and sells ads or subscriptions to its portal. The real value of the so-called BitTorrent broadcaster would be in highlighting the good stuff, much as the collaborative filtering of Amazon and TiVo helps people pick good material. Eric Garland, CEO of the P2P analysis firm BigChampagne, says, "the real work isn't acquisition. It's good, reliable filtering. We'll have more video than we'll know what to do with. A next-gen broadcaster will say, 'Look, there are 2,500 shows out there, but here are the few that you're really going to like.' We'll be willing to pay someone to hold back the tide."

Of course, peercasting doesn't change everything. Producing a good show like The Sopranos or E.R. still costs millions. Actors aren't cheap. That's why Jarvis thinks the first creators to thrive in a BitTorrent world will be a fresh crop of how-to and reality shows, where talent is inexpensive and scriptwriters unnecessary. "Trading Spaces is probably $100,000 a half hour. But with a Mac and a digital video camera you can produce a much cheaper version," Jarvis says.

The major networks are watching the situation cautiously. They don't want to ignore the potential of the peercasting model, but they can't endorse it without knowing where their revenue will come from. "We're going to have to be very creative about it," says Channing Dawson, a senior vice president with Scripps Networks, which produces several food and lifestyle shows for on-demand TV. "But eventually the consumer will become the programmer. Content will be accessible anywhere, anytime." The executive vice president for research and planning at CBS, David Poltrack, elaborates: "In our research with consumers, content-on-demand is the killer app. They like the idea of paying only for what they watch." The trick, he figures, is to work out a solution before the audience for illegal downloading becomes truly huge. He figures the networks have 10 years.

The task for broadcasters is clear: Take this new platform and mine it for gold, the way Hollywood, which squawked about VHS, figured out how to make billions off video rentals. BitTorrent isn't the only way to do this. There are more corporate-friendly routes. The P2P technology company Kontiki produces software that, like BitTorrent, creates hyperefficient downloads; its applications also work with Microsoft's digital rights management software to keep content out of pirate hands. The BBC used Kontiki's systems last summer to send TV shows to 1,000 households. And America Online now uses Kontiki's apps to circulate Moviefone trailers. In fact, when users download a trailer, they also download a plug-in that begins swapping the file with others. It's so successful that when you watch a trailer on Moviefone, 80 percent of the time it's being delivered to you by other users in the network. Millions of AOL users have already participated in peercasting - without knowing it.

The Pirate Bay is a BitTorrent tracking site in Sweden with 150,000 users a day. In the fall, it posted a torrent for Shrek 2. Dreamworks sent a cease-and-desist letter demanding the site remove it. One of the site's pseudonymous owners, Anakata, replied: "As you may or may not be aware, Sweden is not a state in the United States of America. Sweden is a country in northern Europe [and] US law does not apply here. … It is the opinion of us and our lawyers that you are fucking morons." Shrek 2 stayed up.

For movie industry insiders, file-sharing seems like all downside. Unlike TV networks, movie studios get no revenue from advertising - getting massive online circulation won't put a penny in their box offices. For them, it seems like an open-and-shut case. They ran advertisements urging users not to download movies illegally; when that didn't work, they started suing.

"We consider it a regrettable but necessary step," says John Malcolm of the MPAA. "We saw the devastating effect that peer-to-peer piracy had on the record industry."

The music industry watched songs get stolen for years, yet as soon as it gave people what they wanted - a reasonably cheap and easy way to pay for individual tracks - customers swarmed to the legal option: the iTunes Music Store. What if the movie industry pursued a similar model? Use peercasting to distribute movies cheaply, and make it so easy and inexpensive that most of people will go the legal route. As BigChampagne's Garland points out, the film industry might even find that it will be easier for them to bring customers to its side than it is for the music industry, because Hollywood doesn't suffer from the problems that plagued the record business. Music buyers had long felt bitter about album prices. Moviegoers generally do not feel that way about films. While music consumers want to own their MP3s forever, movies are usually a one-hit blast - fewer viewers will want to permanently own the movies. That means creating a digital rights management system for downloadable movies is likely to be a lot easier than it is for music. Music lovers hate DRM limits on their MP3s because they expect their music to behave like a piece of property - something they can own forever and transfer from device to device. In contrast, Blockbuster has long proven that people are happy to just rent movies.

Either way, the lawsuits place Cohen in the crosshairs. The record industry sued Napster into oblivion. Could the MPAA do the same thing to him? Legal experts doubt it. The courts have argued in recent years that a file-sharing technology cannot be banned if it has "substantial noninfringing uses" - in other words, if it can be used for legal purposes. BitTorrent passes that test, says Fred von Lohmann, a lawyer at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, because Linux groups and videogame companies regularly use it to shuttle software around the Net. "That puts Bram in the same situation as Xerox and its photocopiers," he says.

Cohen knows the havoc he has wrought. In November, he spoke at a Los Angeles awards show and conference organized by Billboard, the weekly paper of the music business. After hobnobbing with "content people" from the record and movie industries, he realized that "the content people have no clue. I mean, no clue. The cost of bandwidth is going down to nothing. And the size of hard drives is getting so big, and they're so cheap, that pretty soon you'll have every song you own on one hard drive. The content distribution industry is going to evaporate." Cohen said as much at the conference's panel discussion on file-sharing. The audience sat in a stunned silence, their mouths agape at Cohen's audacity.

Cohen seems curiously unmoved by the storm raging around him. "With BitTorrent, the cat's out of the bag," he shrugs. He doesn't want to talk about piracy and the future of media, and at first I think he's avoiding the subject because it's so legally sensitive. But after a while, I realize it simply doesn't interest him much.

He'd rather just work on his code. He'd rather buckle down and figure out new ways to make BitTorrent more efficient. He'd rather focus on something that demands crazy, hair-pulling logic. In his office, he roots through his bin of twisting puzzles and pulls out CrossTeaser, an interlocking series of colored x's that you have to orient until their colors line up. "This is one of the hardest I've ever tried, " he says. "It took me, like, a couple of days to solve it."

Cohen has even started sketching out ideas for his own puzzles. He dreams of making enough money to buy a 3-D prototyping machine and retire. Now that, he figures, would be a fun life: Sitting at home and designing stuff so fiendishly hard almost no one can figure it out. We know his philosophy of what makes a good game; he's got a theory of the perfect puzzle, too.

"The ideal," he says, "is that you appear to be near the end - you've got almost all the colors lined up, and you think it's nearly solved. But it isn't. And you realize that to get that last color in place, you're going to have to do something that jumbles it up all over again."

Sounds like the puzzle he's created for the television and film

How BitTorrent Works

Bram Cohen's approach is faster and more efficient than traditional P2P networking.

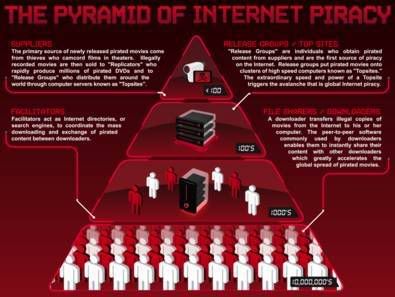

1. A single source file within a group of BitTorrent users, called a swarm, spreads around pieces of a film or videogame or TV show so that everyone has a chunk to share.

2. After the initial downloading, those pieces are then uploaded to other needy users in the swarm. The rules require every downloader to also do some uploading. Thus the more people trying to download, the faster everything is uploaded.

3. Before long, the swarm has shared all the pieces, and everyone has their own complete source.

How Traditional Peer-to-Peer works

Sites like Kazaa and Morpheus are slow because they suffer from supply bottlenecks. Even if many users on the network have the same file, swapping is restricted to one uploader and downloader at a time. And since uploading goes much slower than downloading, even highly compressed media can take many hours to transfer.

Untraceable File Sharing Inspired by Ants

Insects Inspire 'Untraceable' Online File-Sharing Network

http://abcnews.go.com/Technology/FutureTech/story?id=99600

An invasion of ants has become the unlikely inspiration for what may be an untraceable way to trade files online.

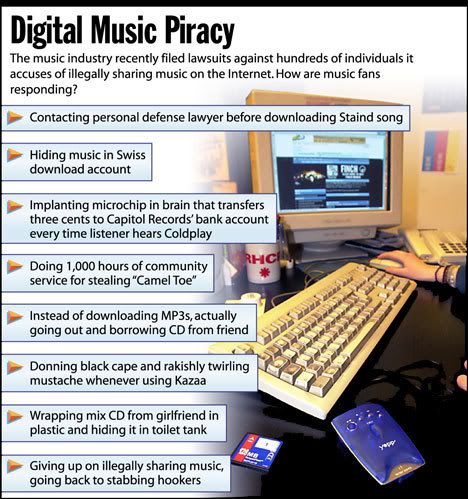

Since last September, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) has filed over 380 copyright infringement lawsuits against suspected online music pirates in the United States. And the effect has been chilling.

A recent Pew survey of online users found just 14 percent still downloading music files from so-called peer-to-peer, or P2P, networks such as KaZaA, compared to 29 percent a year ago. Many cited fears of being nabbed as online "pirates."

Still, the legal clampdown hasn't stopped others, according to a recent survey by market researcher The NPD Group. As many as 12 million individuals claimed to have downloaded music illegally in November — a 9 percent increase in the number of pirates reported in a September survey.

Now Jason Rohrer, a 26-year-old programmer in Potsdam, N.Y., thinks he has a way to really boost file-sharing back into popularity.

When Rohrer was living in Santa Cruz, Calif., and studying for a master's degree in computer science, he noticed a trail of ants had invaded his indoor Ficus tree from the front door. No matter how he tried to destroy the trail — sweeping daily, or blocking the path with chalk or hot pepper — the ants always figured a way around the obstacle to the tree.

"I read about how they use pheromones — chemical scents — to create the trails and how it's used by the colony," says Rohrer. And it inspired him to see if the same "swarm intelligence" could be applied to how programs work over the Internet.

The result: MUTE, freely-available software for a P2P system that Rohrer maintains is almost as hard to trace and stop as, well, ants at a picnic.

Like Foraging Ants, A Circuitous Message Routing

In current P2P networks such as KaZaA and Grokster, software identifies each computer on the network using Internet Protocol (IP) addresses — a string of numbers similar to a telephone number.

When a member searches a P2P network, the request — say for music by Britney Spears — goes out across the network. Computers that have the requested files send a response back directly to the computer that made the request using the IP address.

Files are traded directly between computers in small packets using the IP addresses — making it extremely easy to track.

But MUTE's system has several different ways to thwart tracking efforts.

First of all, each computer on the MUTE network is "addressed" by a random string of characters and numbers. And each time a computer connects to the MUTE network, a new random address is generated.

When a MUTE member searches a file, Rohrer says the request goes out from the originating computer only to nearby computers the program knows about. If the files aren't found there, the MUTE software on those nearby computers then sends out requests to the next set of computers they know about.

Like ants foraging for food, the requests continue on their way across the network. When the file is finally located on the network, the computer that has the file sends the message back to the nearby computer that sent the request, which then passes it on the computer that it received the request from and so on.

Calling for Attention

Rohrer says MUTE's setup offers several advantages over current P2P networks.

For one, chances of finding and retrieving a particular file across the network might be increased since each computer on the network is actively looking and sending data back to the originating computer.

Rohrer compares it to sending a message using the old "telephone" party game.

"Let's say you're in a room crowded with people, one of whom is someone you know," says Rohrer. "To reach that person, you ask the seven people next to you to pass a written message to that person. They may not know the person or where he is in the room, but in turn, they'll copy and pass the note to the people closest to them and so on. Eventually, the person you want to reach gets the message because you've covered everyone in the room."

So while Rhorer's tiny, experimental Mute network has escaped the attention of the RIAA so far, there's no guarantee that the music industry will challenge him and his creation much like they did Shaun Fanning and his Napster creation.

And that leaves it unclear if MUTE will become the latest pest to the RIAA's attempts to thwart piracy, or squashed like the insect that inspired it.

Classified U.S. military info, corporate data available over P2P

Inadvertent data leakage worse than thought, experts tell Congress

http://computerworld.com/action/article.do?command=viewArticleBasic&taxonomyName=privacy&articleId=9027949&taxonomyId=84

Millions of documents, both government and private, containing sensitive and sometimes classified information are floating about freely on file sharing networks after being inadvertently exposed by individuals downloading P2P software on systems that held the data, members of a House committee were told yesterday.

Among the documents exposed: The Pentagon's entire secret backbone network infrastructure diagram, complete with IP addresses and password change scripts; contractor data on radio frequency manipulation to beat Improvised Explosive Devices (IED) in Iraq; physical terrorism threat assessments for three major U.S cities; information on five separate Department of Defense information security system audits.

Information about the breach came during a hearing on inadvertent file sharing over peer-to-peer (P2P) networks held by the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform chaired by Rep. Henry Waxman, (D-Calif.) One of those testifying was retired General Wesley Clark, who is currently a board member of Tiversa Inc., a company that sells P2P network monitoring services to government agencies and private sector companies.

Clark described how "in a matter of hours" he was able to lay hands on over 200 documents containing classified and secret government data from P2P networks using Tiversa's search engine. He came across the documents while preparing for the hearing.

Some of the data appears to have come from the system of a contract worker at the Pentagon who installed P2P software on her computer, Clark said. The data included everything from Iraq status reports to a list of soldiers with their Social Security numbers. "They are the complete documents. They are not faxed copies. They are not smudged. They are as fresh as if they were printed off the computer" of the organization they came from.

"There's all kind of data leaking out inadvertently," he told the committee, noting that the documents he cited were "simply what we found when we put the straw in the water. The American people would be outraged if they are aware of what is being inadvertently being disclosed on P2P networks."

It's not just government data that is leaking out; So is a lot of sensitive corporate information, said Robert Boback, the CEO at Tiversa who also testified at the hearing. In written testimony, Boback listed several examples of corporate information Tiversa was able to pull from P2P networks. It found, for instance, the board minutes of one of the world's largest financial services organization, the entire foreign exchange trading backbone of a financial company and a comprehensive launch plan -- complete with growth targets -- of yet another financial company that was diversifying into a new region. Other corporate documents retrieved from P2P networks included press releases not yet issued, patent information, business contracts and non-disclosure agreements.

In addition, the ready availability of federal and state ID cards, passports, Social Security numbers, credit card information and bank account details make P2P networks a great source of information for identity thieves, he said.

Popular P2P clients such as Kazaa, Lime Wire, BearShare, Morpheus and FastTrack are designed to let users quickly download and share music and video files. Normally, such P2P clients allow users to download files to and share items from a particular folder. But if proper care is not taken to control the access that these clients have on a system, it is easy to expose far more data than intended.

Eric Johnson, a professor of operations management at the Center for Digital Strategies at Dartmouth College's Tuck School of Business, testified that inadvertent data disclosure on P2P networks is a "whole lot worse" than many assume.

Speaking with Computerworld after the hearing, Johnson said that accidental information disclosure on P2P networks has become a "substantial issue for government [agencies] and for banks and for large corporate enterprises. Many companies believe that they have implemented adequate internal controls to block access to P2P networksl, he said. The problem with these types of disclosures is that every employee, contractor, customer or supplier is a potential weak link.

"I spend a lot of time with CISOs and CIOs who think they have locked down their networks and made it difficult for people to join P2P networks," Johnson said. But those controls fail when employees take work home and then connect their systems to a P2P network. "CISOs can do a great job hardening their own networks but controlling what thousands and thousands of individuals do is impossible," he said

One company compromised in this manner is Pfizer Inc. In June, the company disclosed that personal data on about 17,000 employees had been inadvertently exposed on a P2P network after the spouse of an employee used a company computer to access a file sharing network.

Another example is the U.S. Department of Transportation. Daniel Mintz, the department's CIO, offered written testimony about how 93 DOT-related documents were inadvertently exposed on a P2P network. The exposure resulted when the teenage daughter of a DOT worker who was authorized to work at home installed LimeWire's P2P client on the computer containing the DOT data. The accidental data exposure was only discovered after a Fox News reporter informed the employee that he had been able to access several DOT-related documents from her computer, Mintz said.

DOT's inspector general "found that 30 of the approximately 93 DOT-related documents were publicly accessible at the time via LimeWire or other P2P software by virtue of residing in a 'shared folder,'" Mintz said. In addition, about 36 out of approximately 260 National Archives-related documents that were also on the employee's computer were in a shared folder and thus similarly exposed.

House Panel Scrutinizes File-Sharing

House Panel Scrutinizes Peer-To-Peer File-Sharing For Security Threats

http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2007/07/24/ap/hightech/main3094167.shtml

A diagram of a Pentagon computer network that includes passwords to defense contractors' systems is one of hundreds of classified documents accidentally available online, a House panel was told Tuesday.

This and other sensitive information, including personal financial data, is mistakenly leaked through popular file-sharing programs such as LimeWire, KaZaA and Morpheus that individual, corporate and government users use to share music, movie and other entertainment files, several experts said at a hearing by the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee.

"The American people would be totally outraged if they were aware of what is inadvertently shared ... by government agencies," said retired Gen. Wesley Clark, who is on the advisory board of Tiversa Inc., a data security company. Clark did not name the defense contractors whose computing passwords were compromised.

Rep. Henry Waxman, D-Calif., chairman of the committee, said the hearing was intended to scrutinize the threats file-sharing, or peer-to-peer, technology poses to privacy and security, not to ban it.

Waxman and Rep. Tom Davis, R-Va., senior Republican on the committee, said they had examined similar concerns four years ago. Both members introduced a bill in 2003 that would have required government agencies to clamp down on file-sharing, but the legislation wasn't approved.

Robert Boback, Tiversa's chief executive, said that over 300 million searches are conducted through peer-to-peer networks daily, compared to 130 million through Google. While most sensitive information is shared accidentally, users in both the United States and abroad are aware of what is available and actively search for data such as credit card numbers, bank statements, and account passwords.

Mark Gorton, chairman of Lime Wire LLC, said his company "takes the problem of inadvertent file-sharing seriously" and seeks to make it easy for users to understand what files they may be sharing.

But he also said he had "no idea" of the amount of classified information available over peer-to-peer networks.

Other experts downplayed the threat posed by peer-to-peer file-sharing.

Mary Engle, associate director of advertising practices at the Federal Trade Commission, said a 2005 FTC report found that peer-to-peer file-sharing "is a 'neutral' technology," meaning that "its risks result largely from how individuals use the technology rather than being inherent in the technology itself."

Meanwhile, Thomas D. Sydnor, an attorney at the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office, said that distributors of the five leading file-sharing programs continue to include features in their software that can trick users into sharing sensitive and copyrighted files.

Kurt Opsahl, a senior staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said on Monday, before the hearing, that users of file-sharing software need to be educated on how to do so safely, as do users of all kinds of software.

"Why is the focus on peer-to-peer?" Opsahl said. "Is that furthering another agenda?," he added, referring to the entertainment industry's criticism of the practice.

Can File-Sharing Impact Future Employment?

http://www.slyck.com/story1184.html

University and college students aren’t exactly well known for staying within the confines of the law. Sex, drugs and rock n’ roll are part of the college experience; a time when depravity, decadence and moral ineptitude bring out the best in us. But by all means, don’t copy that floppy.

So says the BSA (Business Software Alliance), a trade organization that represents the intellectual property rights of member companies such as Apple, Adobe, IBM, and Microsoft. Similar in function to the RIAA or MPAA, the BSA has struggled to maintain the line against online file-sharing.

Much like the music and movie industries, the BSA has spent considerable effort on educating students on the potential adverse financial effects of unathorized file-sharing.

Unlike sharing music and movies online however, private file-sharers are generally immune from widespread lawsuits. Yet this doesn’t mean the BSA is ignorant. As part of the BSA’s educational effort, the software trade organization has released a study with the intent to influence the sharing habits of students ready to enter the workforce.

The study, published on the BSA educational site DefineTheLine.com, was conducted by BusinessWeek Research Services. Note this was not an independent study, rather one commissioned by the BSA.

The research’s primary foundation is to convey that past file-sharing habits could have an impact on future job potential. According to the study, a “vast majority of Managers (86%) say that applicants’ file-sharing attitudes and behaviors have an impact on their hiring decisions.”

Understandably, those responsible for interviewing potential employees felt that an applicant’s philosophy towards workplace file-sharing influenced the hiring process. “If they company knew that a job applicant had lax attitudes toward illegal file-sharing in the work place, they would probably (23%) or definitely (6%) reject the candidate (total of 29%).”

Oddly enough, the study found that if a company had knowledge the “job applicant had improperly obtained or shared files [privately] in the past, they would probably (24%) or definitely (10%) reject the candidate (total of 34%)” – an increase of 5% over workplace file-sharing.

While the study is aimed to educate and deter students nearing graduation, its noteworthy to point out employers also appear to have lax attitude towards file-sharing – especially on corporate networks. A surprisingly small number (less than 1/3) felt that a lax attitude towards workplace file-sharing would impact their hiring decision. The BSA could benefit by capitalizing on the fact there’s little sympathy for those caught sharing on corporate networks and focus their educational efforts on employers as well.

Over 950 businesses from all ranges of corporate America were surveyed, such as consulting, manufacturing, marketing, banking, technology, and healthcare firms. Yet the question remains, does past file-sharing have an impact on future employment? Perhaps that’s a question best answered by Bram Cohen or Shawn Fanning.

File-sharing 'not cut by courts'

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/4627368.stm

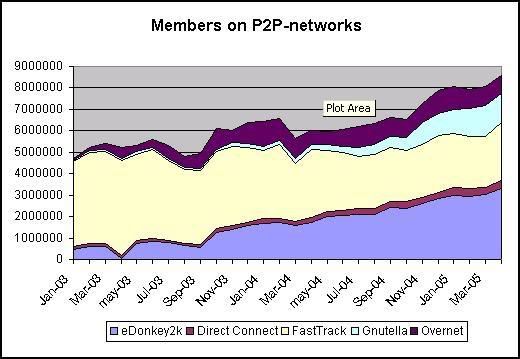

Global court action against music file-sharers has not reduced illegal downloading, an industry report says.

The level of file-sharing has remained the same for two years despite 20,000 legal cases in 17 countries.

The International Federation of the Phonographic Industries (IFPI) said it was "containing" the problem and more people were connecting to broadband.

The global music industry trade body said sales of legal downloads were worth more than $1bn (£570m) in 2005.

That is up from $380m (£215m) in 2004, with "significant further growth" predicted this year.

Download stores now offer two million songs - double the number available a year ago - and the total number of legal downloads shot up to 420 million in 2005.

IFPI chairman John Kennedy said the industry was "winning the war but we haven't won the war" against piracy.

The fact that illegal song-swapping had not increased should be regarded as a success, he told the BBC News website.

"I would love to be sitting here telling you that it had gone down," he said.

"As broadband rolls out and as there's an explosion in many countries of broadband, file-sharing is being contained."

But the industry was finding it difficult to persuade existing song-swappers to use legal download services such as iTunes instead, he said.

"Those who've got into the habit of consuming their music for free are very difficult to shift.

More court cases

"And frankly it's an argument for increasing the scale of court cases because at the moment, people still don't think it's going to be them."

There are currently about 870 million song files available to download illegally over the internet, according to the IFPI.

Mr Kennedy also warned that the music industry could sue internet service providers (ISPs) if they do not crack down on their customers who flout copyright rules.

Music piracy could be "dramatically reduced within a very short period of time" if ISPs took action against their law-breaking customers, Mr Kennedy said.

The IFPI's Digital Music Report also revealed that music downloaded onto mobile phones was now worth $400m (£227m) per year - 40% of the digital music business.

'Misunderstood'

And Mr Kennedy backed the continuing use of Digital Rights Management (DRM) technology, which controls what consumers can do with their music once it has been purchased - either online or on CD.

DRM remains controversial, with some critics arguing it does little to prevent piracy but instead limits what consumers fairly should be able to do with their music.

Earlier this week, the National Consumer Council complained that DRM was eroding established rights to digital media.

Mr Kennedy, writing in the report, said DRM "helps get music to consumers in new and flexible ways".

He said DRM was a "sometimes misunderstood element of the digital music business".

Legal download sales pass $1bn a year

A library of two million songs legally available

420 million singles downloaded in 2005

19,400 people sued for illegal song-swapping to date

335 legal online music services available

35% of illegal file-sharers have cut back*

14% of illegal file sharers have increased activity*

One in three illegal file-sharers buy less music*

Recording Industry Association of America

The Recording Industry Association of America (or RIAA) is a trade group that represents the recording industry in the United States. Its members consist of a large number of private corporate entities such as record labels and distributors, who create and distribute about 90% of recorded music sold in the US. It is involved in a series of controversial copyright infringement legal actions on behalf of its members.

The RIAA was formed in 1952 primarily to administer the RIAA equalization curve. This is a technical standard of frequency response applied to vinyl records during manufacturing and playback. The RIAA has continued to participate in creating and administering technical standards for later systems of music recording and reproduction, including magnetic tape, cassette tapes, digital audio tapes, CDs and software-based digital technologies.

The RIAA also participates in the collection, administration and distribution of music licenses and royalties.

The association is responsible for certifying gold and platinum albums and singles in the USA. For more information about sales data see List of best selling albums and List of best selling singles.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RIAA

The RIAA's stated goals are to protect intellectual property rights worldwide and the First Amendment rights of artists; to perform research about the music industry; and to monitor and review relevant laws, regulations and policies

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RIAA

RIAA says lawsuits cannot be the complete answer to music piracy

http://www.tgdaily.com/content/view/33022/120/

The Recording Industry Association of America’s massive lawsuit campaign to crack down on music pirates has generated a lot of bad PR, while any good that has come out of it remains controversial at best. In a recent conversation with TG Daily, the RIAA acknowledged that suing potential customers “was not the answer,” while adding that the lawsuits were “a necessary part of a larger equation.”

“Litigation tends to generate more heat, friction, and headlines,” Jonathan Lamy, a spokesman for the RIAA told us. “What is the most important anti-piracy strategy is aggressive licensing and offering great legal alternatives. That is what our member companies obviously do and our job is to complement that, which is the most important thing to do to win over fans.”

According to the latest statistics from the RIAA, there were over 7.8 million households in March 2007 in the U.S. that illegally downloaded music versus 6.9 million households in April 2003, when the litigation campaign began. However, while this number suggests that the lawsuits have been counter-productive there is also the fact that the broadband penetration rate in the U.S. has also more than doubled since 2003.

Still, whether or not the litigation has had much of an effect in mitigating piracy, the benefits for society, as well as for the recording industry, remain debatable.

“I don’t think [the litigation] has made a meaningful dent in how much piracy goes on among American young people,” John Palfrey, a clinical professor of law at Harvard Law School and executive director of the Berkman Center for Internet and Society. “And I think it continues to represent a signal that the recording industry is out of step with the future, and frankly out of step with the present as well [….] But it is more importantly, I think, a distraction from finding the way forward in a digital age.”

Besides its questionable benefits, the RIAA’s lawsuit dragnet that has involved over 21,000 legal actions in the U.S. since 2003 and has ensnared some innocent parties in its wake.

One such person wrongly accused was Tanya Andersen, a single mother who is also disabled, against whom the RIAA only recently dismissed its lawsuit against her for allegedly having shared 1400 pirated music files.

The claim was dismissed with “prejudice,” meaning that the RIAA or the record companies it represents must pay her attorney fees.

But the RIAA’s dismissal of the case came after more than a year after Ms. Andersen first received a letter from RIAA lawyers claiming she was liable for a minimum of $750 for each of the 1400 songs they claimed she downloaded.

Ms. Andersen, who had never heard of the songs and artists she allegedly pirated then offered to surrender her computer as proof that she had not downloaded the files. But instead, the RIAA’s continued to litigate with same zealousness as if it were going up against a large corporation.

Ms. Andersen’s eventual legal victory is but one example of other dismissals of RIAA cases, which were dropped after over a year of depositions, trials, and numerous other time-consuming procedures the defendants were subjected to but not compensated for.

Federal judges have rejected RIAA’s legal claims in federal courts in Oklahoma, New York, and in Michigan.

Some of the defendants are taking a more aggressive approach in fighting back. Defendant Suzy Del Cid in Florida recently filed a counter claims against UMG for computer fraud and abuse, extortion and trespassing when her computer was accessed.

As far as bad PR goes, it does not get much worse when a multi-million dollar legal machine wrongfully attacks single mothers with limited financial resources to fight back. But instead, the RIAA has extended its litigation campaign.

The RIAA has begun to target college campuses, much to the ire of university officials and some politicians. In what it called a “fifth wave” of pre-litigation letters, the RIAA said its lawyers have sent over 395 letters to 19 universities demanding settlement fees. The organization also has asked universities to forward copyright infringement complaints to students for file sharing on school networks to; reactions are pouring in and not all universities said they will follow the idea: Harvard was among the first that said that it will ignore the RIAA’s request. Instead, more and more universities are beginning to enforce their own piracy policies: For example, the University of Kansas is reported to have implemented a new copyright infringement policy for the students, which says that students who are caught downloading copyrighted material will lose their privileges on the university’s residential network “forever”.

From the view of the RIAA, it is unlikely that the litigation will end anytime in the near future.

“They know what they are doing. They are not going to wake up one morning and say ‘oh, gee, there is a new method of distributing music,’” Lory R. Lybeck, Andersen's attorney from Lybeck Murphy of Mercer Island, Washington, said. “I think what it is going to take is for the artists and the general public to say ‘you guys are dead. You’ve been dead for a long time.’”

The settlement fees are certainly not paying for the litigation costs, either, Ray Beckerman, a New York-based attorney with Beldock Levine & Hoffman, who has represented defendant clients against RIAA claims, said.

“It has cost them more than they've collected,” Beckerman said in an email. “They've accomplished nothing, other than to create a whole class of people who are boycotting their product.”

In fairness, the majority of the 21,000 IP addresses targeted for illegal file downloads in the U.S. are probably at fault in the legal sense. Litigation is by no means the only strategy the recording industry employs to thwart music file pirating, either.

“No one relished having to take all these actions, but they have undeniably played a big role in raising awareness that unauthorized file-sharing is illegal and they have helped contain levels of file-sharing,” a spokesman for the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry - the international equivalent of the RIAA – wrote to us in an email. “But legal actions are in no way a strategy in isolation - making great music services available is key, as is public education. At the same time it’s recognized that, effective as they are, lawsuits against illegal-file sharing are only the second best way to stop mass piracy on the internet.”

Instead, the recording industry’s main emphasis is more focused on the ISPs, the spokesman said. “They have the ability and the opportunity to make a huge difference simply by enforcing their terms and conditions against people file-sharing on their networks and disconnecting infringers,” the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry said.

But while statistic show that the RIAA is getting its message across that downloading music files without paying for them is illegal, many do not deem sharing files from a CD that they or someone else has paid for as stealing or morally wrong. People know that smoking marijuana or driving above the speed limit without endangering the welfares of others, are against the law, for example, but people do not necessarily see these acts as immoral.

“[Studies] show a continued sense on the part of American young people that file sharing may be wrong on the law but it is acceptable as a moral matter,” Palfrey said.

The artists who stand to lose money are often hardly advocates of the massive litigation campaign, either.

Rick Mason, for example, the drummer for Pink Floyd recently told this writer how he believed that artists need to be paid for their work, but that lawsuits were the wrong approach.

Instead, artists’ compensation should increase with new music distribution methods, Lybeck said. “They should let the music authors actually share some of the profit, which [the RIAA] has had a strong hold on in the distribution scheme for 50 years,” Lybeck said. “There is a whole new distribution capability, and the [RIAA] guys are not needed--and they know it.”

RIAA Accused Of Illegal Investigations

http://www.informationweek.com/news/showArticle.jhtml?articleID=200900640&subSection=All+Stories

A Texas woman asks a court to bar the music companies from using unlicensed firms when they build their legal cases against illegal file sharing.

Another target of a music file-sharing lawsuit is fighting back, claiming in a countersuit that record companies' investigatory tactics were illegal.

Texas resident Rhonda Crain claims that Sony BMG Music Entertainment and others in the Recording Industry Association of America lawsuit illegally employed unlicensed investigators and were aware that they were disregarding the laws of her state. She filed an amended counterclaim Monday in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas, Beaumont Division.

Court documents claim that the plaintiffs in the original lawsuit "agreed between themselves and understood that unlicensed and unlawful investigations would take place in order to provide evidence for this lawsuit, as well as thousands of others as part of a mass litigation campaign. On information and belief, the private investigations company hired by plaintiffs engaged in one or more overt acts of unlawful private investigation. Such actions constitute civil conspiracy under Texas common law." The counterclaim states that the companies promoted or incited illegal investigations of Texas residents.

Crain is claiming emotional distress and that she has been forced to spend resources and time defending the "ill-conceived" lawsuit. She has requested that the court bar the music companies from using unlicensed firms during the discovery process against her and in all other Texas lawsuits. She is also seeking "all other relief as the court may deem equitable and proper including an award of damages." Finally, she is asking the court to throw out the case.

Crain claimed earlier that she did not infringe on copyright-protected music. Her lawyer, John Stoneham, has argued that the plaintiffs failed to show that they own or license the recordings that Crain allegedly infringed upon, did not identify the recordings in question, and failed to indicate where and when the alleged infringement took place.

Stoneham said nobody ever contacted Crain or tried to stop the alleged infringement before taking the matter to court and the only evidence produced in the case was a screenshot showing a peer-to-peer file-sharing program and Crain's status as an account holder with an Internet service provider.

The screenshots point a finger at file-sharing network, KaZaA, which has already reached a settlement with the record companies, he said. That should cover all copyright infringement damages that occurred on the network, including any alleged involvement on Crain's behalf, Stoneham argued. He said the $115 million covers any and all injuries resulting from file-sharing on the network, and the plaintiffs are barred for recovering damages twice for the same alleged infringements. Stoneham also argued that the exhibits in the case fail to link the screenshots with an IP address or, in any other way, link specific individuals with the alleged infringement.

"Plaintiff's actions amount to extortion," Stoneham said in court documents. "Plaintiffs did not seek to mitigate their damages, if any; instead they filed their Complaint which was served upon Defendant with a cover letter offering to enter into settlement negotiations."

The document explains that Crain contacted the companies' lawyers and learned she could settle the case for $4,500, which Stoneham called "grossly disproportionate to the amount claimed in the settlement letter."

Crain is seeking reimbursement for the cost of defending a lawsuit that Stoneham called frivolous.

A lawyer for the defendants referred calls to the Recording Industry Association of America. Representatives there could not be reached immediately for comment.

CRACKSDOWN ON FILE SHARING

Pirated Music Helps Radio Develop Playlist

http://online.wsj.com/public/article/SB118420443945664247-LO5CbEkUSQBDobMKFSTfygkJUr8_20070810.html?mod=tff_main_tff_top

The music industry has long blamed illegal file sharing for the slump in music sales. But now, a key part of the industry is trying to harness file sharing to boost its own bottom line.

Earlier this year, Clear Channel Communications Inc.'s Premiere Radio Networks unit began marketing data on the most popular downloads from illegal file-sharing networks to help radio stations shape their playlists. The theory is that the songs attracting the most downloads online will also win the most listeners on the radio, helping stations sell more advertising. In turn, the service may even help the record labels, because radio airplay is still the biggest factor influencing record sales.

Premiere's Mediabase market-research unit is working on the venture with the file-sharing research service BigChampagne LLC. BigChampagne collects the data while a Premiere sales force of about 10 people pitches the information to radio companies and stations. Premiere declined to disclose how much it charges.