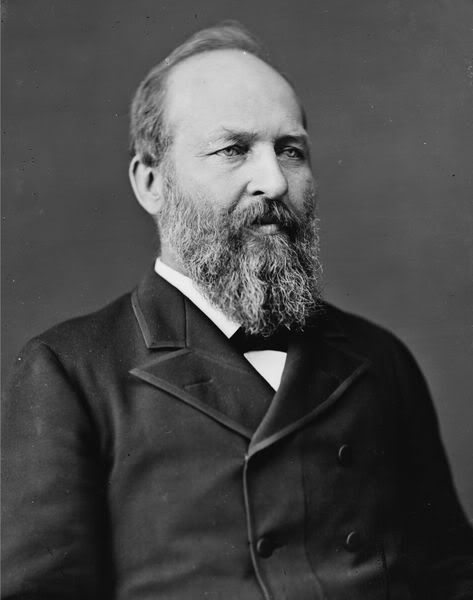

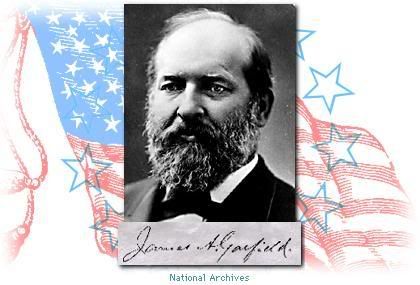

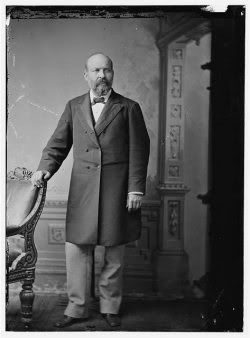

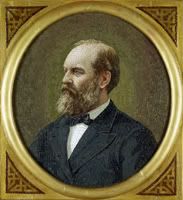

James Abram Garfield

20th President of the United States

(March 4, 1881 to September 19, 1881)

Nickname: None

Born: November 19, 1831, in Orange, Ohio

Died: September 19, 1881, in Elberon, New Jersey

http://www.ipl.org/div/potus/jagarfield.html

Born in a log cabin to poor, uneducated parents, James Garfield went on to be a scholar, a Civil War hero, a U.S. congressman for eighteen years and, eventually, president of the United States. Unfortunately, Garfield's rags-to-riches story came to an abrupt end when a disgruntled Republican supporter, Charles Guiteau, shot Garfield twice on 2 July 1881. Garfield lingered on through the summer and died in Elberon, New Jersey on 19 September 1881. His vice president, Chester A. Arthur, was sworn in as president on 20 September 1881.

http://www.answers.com/topic/james-garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831–September 19, 1881) was the 20th President of the United States and the second U.S. President to be assassinated — Abraham Lincoln was the first. Garfield had the second shortest presidency in U.S. history, after William Henry Harrison's. Holding office from March 5 to September 19, 1881, President Garfield served for a total of six months and fifteen days.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Garfield

American President: President James Abram Garfield

http://www.millercenter.virginia.edu/academic/americanpresident/garfield

James Abram Garfield Speeches

http://millercenter.virginia.edu/scripps/digitalarchive/speechDetail/55?PHPSESSID=48fe5830d9ce824b710fcbc0ee2adde2

James Abram Garfield

http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/entry.php?rec=170

James Abram Garfield was born on November 19, 1831, in Orange, Ohio. Garfield's father died in 1833, and James spent the majority of his youth working on a farm to care for his widowed mother. At the age of seventeen years, Garfield took a position on the Ohio and Erie Canal, steering the boats through the canal.

During his youth, Garfield received minimal schooling in Ohio's common schools. In 1849, he enrolled in the Geauga Seminary in Chester, Ohio. After briefly serving as a teacher, Garfield attended the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (modern-day Hiram College) in Hiram, Ohio. He transferred to Williams College, in Williamstown, Massachusetts, graduating in 1858. He returned to Hiram College that same year as a professor of ancient languages and literature. He also served as Hiram's president until the outbreak of the American Civil War. In 1859, Garfield embarked upon a political career, winning election to the Ohio Senate as a member of the Republican Party.

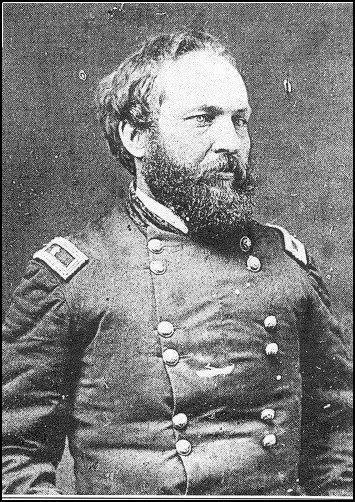

During the Civil War, Garfield resigned his position at Hiram College at joined the Union Army. He began as lieutenant-colonel of the Forty-Second Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment. He participated in the Battles of Shiloh and Chickamauga. He resigned from the army on December 5, 1863, having attained the rank of major general.

Garfield resigned his commission because Ohio voters had elected him to the United States House of Representatives. He served nine consecutive terms in the House of Representatives before he was elected President of the United States in 1880. In Congress, Garfield was a supporter of the Radical Republicans. He opposed President Andrew Johnson's lenient policy toward the conquered Southern states and also demanded the enfranchisement of African-American men. He was appointed by the Ohio legislature to the United States Senate in January 1880, but he declined the office, because he was elected president a few months before he was to claim his seat in the Senate.

As president, Garfield accomplished little. He served only four months before he was shot by Charles J. Guiteau. Guiteau had sought a political office under Garfield's administration. He was refused. Disgruntled, Guiteau shot Garfield while the president waited for a train in Washington, DC. Garfield clung to life for two more months, before dying on September 19, 1881. While Garfield accomplished little as president, his death inspired the United States Congress and his successor as president, Chester A. Arthur, to reform civil service positions. Rather than having the victors in election appointing unqualified supporters, friends, or family members to positions, the Civil Service Commission was created to guarantee that political appointees were qualified for positions.

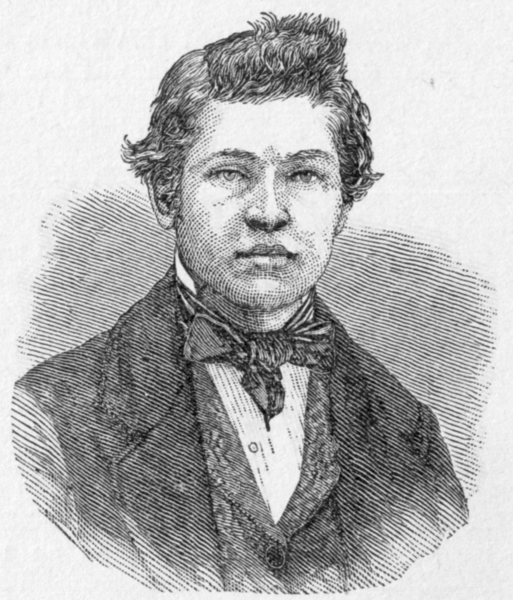

Charles Julius Guiteau (September 8, 1841 – June 30, 1882) was an American lawyer who assassinated President James A. Garfield on July 2, 1881. He was sentenced to death by hanging in 1882.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Julius_Guiteau

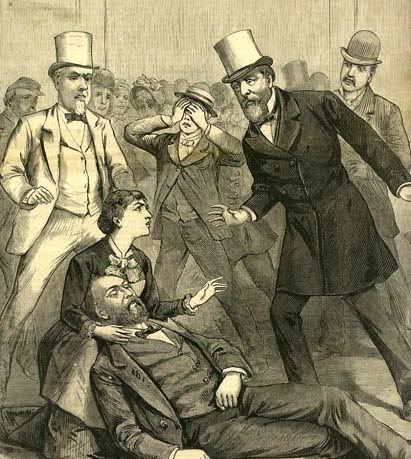

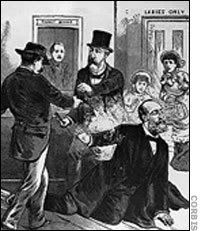

Despite the heat of the morning, James Garfield was in good spirits. President since the March, after narrowly defeating fellow Civil War General Winfield Hancock, Garfield had anticipated a tough start, and there had been deep opposition and debate to every appointment and program his administration had suggested. The country was still healing the divisions caused by the War Between the States, and even Garfield's Republican party was trying to settle its own conflicts, as the Republicans were divided into two distinct camps: the Stalwarts, who had wanted to nominate former President Ulysses S. Grant for another term, and the Half-Breeds, who had gained just enough ground to get Garfield onto the ballot and into the White House.

http://www.crimelibrary.com/terrorists_spies/assassins/charles_guiteau/index.html

But on this July morning, Garfield was taking a break from the conflicts of the presidency and was off for a brief vacation. He was in a good mood, reportedly doing handstands for his sons before dressing and seeing to the final details of the journey.

Soon after 9:00 a.m., Garfield and a few of his political entourage, including Secretary of State James Blaine, arrived at the Baltimore & Potomac Railroad station. They walked quickly through the throng of other holiday-makers and headed toward the lines of departing trains.

An observer in the station that morning would not have noticed anything unusual: the normal activity around the ticket window, a mother disciplining her child, people sitting on benches with their faces hidden by newspapers.

From out of the crowd, a small man approached Garfield from behind and quickly fired two shots at the president -- one shattering bones and puncturing vessels and arteries before coming to rest somewhere deep inside the internal organs.

Feeling more confusion than pain, Garfield crumpled to the floor.

The shooter stepped quickly back into the crowd.

Suddenly there was a panic -- people shouting and running in every direction: to get help, to flee, to get a closer look at what had happened.

The shabbily dressed gunman began to leave the station through one of the many exits, but an observant guard grabbed him and was mildly surprised when the little man put up no resistance.

In the flurry of activity that followed, Garfield was carried out of the station and his assailant hurried off to a local jail.

So began the events that would see Charles Guiteau into the history books as the assassin of President Garfield, the second president in U.S. history to be assassinated -- although Guiteau's bullet was not the actual cause of Garfield's death.

To say that Garfield was born into a hard life would be an understatement. According to Justus Doenecke's book The Presidencies of James A. Garfield & Chester A. Arthur, Garfield was born in 1831 "in a rude hut near Orange, Ohio." His mother was widowed soon after Garfield was born, and the young boy spent his early years working long days on the family farm. As he came of age, he would add to the family's meager fortunes with any other work he could find, including a brief time driving a barge on the rivers of the area. Indeed, his rags-to-riches life inspired Horatio Alger Jr., a classic novelist of such tales, to write the biography From Canal Boy to President in 1881.

Doenecke points to a religious awakening at 18 as a major turning point in Garfield's life, leading to his attendance at college, some time spent considering the ministry as his vocation, and his entry into politics in 1859 as the youngest member of the Ohio Legislature.

He continued to rise steadily up the Republican party ladder before becoming its presidential candidate in 1880.

Born into better financial circumstances (but in many ways an equally bleak childhood), Charles Julius Guiteau came into the world in September 1841 in Freeport, Illinois. Georgetown University's Lauinger Library, which holds a special collection of Guiteau-related documents, states that Charles was the fourth child born to businessman Luther Guiteau and his wife Anne. Two more children followed Charles, and Anne died when Charles was barely 7 years old. Although Luther would later remarry, the Lauinger Library maintains that his sister Frances "practically raised" Charles and would become his substitute mother and primary source of "moral and financial support" for most of his life.

He would choose a disturbing way to repay her for her kindness.

The Freeport locals generally thought the whole Guiteau family was odd, and there was whispered gossip about insanity in the Guiteau gene pool. The Lauinger Library collection includes a letter from one acquaintance of the family to another saying:

I remember of hearing you tell of the funny and strange actions of the Guiteaus. ...I believe that both Charles and his father were (crazy when it came to) religion...write to me stating the peculiar transactions of...old man Guiteau.

Luther was a strange and stern father, and young Guiteau received many whippings and streams of verbal abuse throughout his childhood. As sometimes happens with children raised in this kind of oppressive environment, Guiteau coped with his father's abuse -- and his own resulting feelings of worthlessness -- by developing an inflated sense of self-importance that would later irritate everyone he came into contact with. When people refused to see him as a luminary, Charles would be confused, but he would grow to deny anything that contradicted his own grandiose vision of himself and would refuse to see the reality of his few and pitiful accomplishments.

As noted in the neighbor's correspondence, Luther's religious beliefs were seen as odd by the society of that time. Luther was an ardent follower of John H. Noyes and Noyes's teachings that promoted communal living, multiple sex partners, and other beliefs that were seen as questionable (if not downright evil) by Victorian society.

Young Guiteau also came to believe in Noyes's doctrines and, after reaching adulthood, traveled in 1860 to live in the Oneida Community, a New York commune that was the center of Noyes's cult.

With his inflated ego and abrasive personality firmly in place, Guiteau rubbed most members of Oneida the wrong way. And when it came to enjoying Oneidas' loose sexual morality, Guiteau repelled more women than he attracted. Indeed, in the several years he was living at Oneida, Guiteau would later testify that he had "remained strictly virtuous...aside...from three distinct women in a very short time."

Communal living did not agree with Guiteau. He no doubt wanted to be seen as better than the rest of the residents. The History House -- whose Web site includes many original documents and trial transcripts quoted throughout this article -- cites a letter from an Oneida elder to Luther complaining that Guiteau had:

..a decided repugnance to labor with his hands, and indeed to business of all kinds. He wrote Noyes a long communication, in which he was very insolent, charging him with tyranny and oppression.

The letter concluded with the opinion that Guiteau had "an unsound insane mind."

It would not be the last time that someone in authority reached that conclusion.

Guiteau left Oneida in 1865 and, regardless of supposedly believing him to be an oppressive tyrant, attempted to set up a newspaper in New Jersey that would, according to the Lauinger Library, spread Noyes's teachings.

The newspaper never got off the ground, and, only 14 weeks after leaving, Guiteau rejoined Oneida. He immediately resumed his feelings of superiority over the other commune members, and tensions quickly escalated to a point where Guiteau left Oneida for good on November 1, 1866.

Out on his own, Guiteau began a long history of shady business practices, sneaking out of his lodgings in the dead of night without paying his bills, short stays in jail, and moving around to keep a step ahead of his growing number of creditors.

After Oneida, Guiteau attempted to sue Noyes and the community for what he felt was owed him for all the work he had done during his residency. Pointing out that work done in a communal living environment is done, by definition, for no payment, Noyes refused to make any monetary settlement. Guiteau then considered blackmailing Noyes by going public with lurid stories of rampant sex in Oneida. When, according to the Lauinger Library, Oneida countered by threatening to have him prosecuted for attempted extortion, Guiteau gave up and moved to Chicago.

In 1869, Guiteau married Annie Bunn, who worked at the Chicago YMCA he attended. By the time of their wedding, Guiteau had struggled through the Illinois Bar exam and had established a small legal practice, but his pattern of questionable ethics and business failures continued.

Once he realized that Chicago held no further hope for his big dreams, and no doubt with many creditors on the hunt, he and Annie left Chicago for New York City.

Rick Geary's The Fatal Bullet states that Annie successfully sued for divorce in 1874 on the grounds of adultery once it became known that Guiteau had contracted syphilis from a prostitute. That Annie had stayed for five years is remarkable; as the Lauinger Library's Web site says, Guiteau "...was abusive to his wife, reportedly locking her in a closet for whole nights."

New York City held no better fortunes for Guiteau than Chicago had. Now on his own, lack of money continued to plague Guiteau, although his massive ego kept him convinced that his prosperity would bloom as soon as one of his brilliant ideas resulted in the money and prestige he deserved.

Still dodging creditors and landlords, he moved about frequently, and some of those creditors approached his brother John for the settlement of Guiteau's many debts. When John wrote to Guiteau about the urgency to pay back the debts, Guiteau was outraged and wrote John a reply:

Find seven dollars enclosed. Stick it up your bung hole and wipe your nose on it, and that will remind you of the estimation in which you are held by Charles J. Guiteau. Sign and return the enclosed receipt and I will send you (the money), but not before. And that, I hope, will end our acquaintance.

Guiteau didn't turn his back on his entire family, however. After a brief stay in jail (which Geary states was due to trying once again to vacate his residence without paying), he went to live with his sister Frances and her family.

After a few months, however, according to Lauinger Library's Web site, Guiteau attempted to attack Frances with an ax he was using to chop wood. There was no apparent reason for the spontaneous attack, and Frances ran to a local doctor who recommended that she have her brother institutionalized. Guiteau fled the area before Frances could take any action.

Without a home or income, his journalistic and legal careers in the dust, Guiteau began a string of speaking appearances to take advantage of the many religious revival "meetings" that crisscrossed the country in the late 19th century.

If he hoped to become more successful as a traveling preacher than in his earlier occupations, however, he was to be disappointed. One newspaper article that appeared after one of his nearly-incoherent religious lectures said:

Is There a Hell? Fifty deceived people (believe) that there ought to be. Charles J. Guiteau (if such really is his name), has fraud and imbecility plainly stamped upon his (face). (After) the impudent scoundrel talked only 15 minutes, he suddenly (thanked) the audience for their attention and (bid) them goodnight. Before the astounded 50 had recovered from their amazement...(he had taken their money and) fled from the building and escaped.

As 1880 approached, Guiteau took stock of his life. Nearing 40, none of his past efforts had led him to the notoriety and fame he felt he was owed.

He could not understand it.

He was a great man, an exceptional man, but nobody was paying him homage.

He wondered if he had just chosen the wrong occupations.

Perhaps, Guiteau thought, he was destined to make his mark in politics.

1880 was an election year. As a lifelong Republican, Guiteau sided with the Stalwarts in the bitter infighting within the party. He wrote letters and speeches in support of the Stalwarts' plan to put Ulysses S. Grant back into the White House. Once the Half-Breeds had narrowly defeated the Stalwarts and put Garfield onto the ticket, Guiteau quickly switched sides and began producing pro-Garfield related documents. The History House claims that on some rallying speeches, Guiteau merely substituted "Garfield" for "Grant," without changing any of the biographical information basically giving Garfield credit for Grant's childhood, decisive battles, and government accomplishments.

After Garfield won the election, the Lauinger Library's Web site notes that Guiteau believed that a little-heard speech he had given in August of 1880 was the primary cause for the Republican victory. He reached this conclusion without any external input whatsoever.

Certain now that he was approaching the great heights he was destined for, and equally certain that the Republican Party (and Garfield in particular) were forever in his debt, Guiteau moved to Washington, D.C., to receive what he felt sure would be an endless stream of honors.

Completely ignored by the new administration, Guiteau nevertheless decided to allow himself to be appointed to an international consulate, and he began writing letters to that effect after his arrival in Washington.

To President Garfield he wrote:

Next Spring I expect to marry the daughter of a deceased New York Republican millionaire and I think we can represent the United States government at Vienna with dignity and grace.

Not receiving any response, Guiteau sent Garfield another letter, more overconfident than the previous:

I called to see you this morning, but you were engaged. (Previously) I sent you a note touching on the Austrian mission. (The current Austrian Consul), I understand, wishes to remain at Vienna till fall. He is a good fellow (and) I do not wish to disturb him in any event.

What do you think of me for Consul-General at Paris? I think I prefer Paris to Vienna...and I presume my appointment will be promptly confirmed.

Still receiving no response from Garfield, Guiteau began writing a stream of letters to various government officials, targeting Secretary of State Blaine in particular:

...in January last I wrote Garfield touching the Austrian Mission, and I think he has filed my application and is favorably inclined. Since then I have concluded to apply for the Consul-General at Paris instead.

I spoke (with Garfield) about it, and he said your endorsement would help, (so I) will talk with you about it as soon as I can get a chance. There is nothing against me. I claim to be a gentleman and a Christian.

The History House states that Guiteau had seen the heiress mentioned in the first letter only once, from a distance -- and it is doubtful that Garfield had read any of Guiteau's letters, let alone advised him to get Blaine's endorsement.

Puzzled by the silence from the administration that owed him so much, but certain that he would be rewarded for his outstanding services, Guiteau increased his letter-writing campaign. Secretary of State Blaine received so many letters and messages from Guiteau that when one day a strange man approached him and identified himself as the persistent author of the letters, Blaine reportedly shouted at Guiteau: "Never speak to me again on the Paris Consulship as long as you live!"

Guiteau was stunned. How could they deny him a position of honor, after his speech and other works had clinched the election?

On hearing the news that the consulate jobs had gone to others, Guiteau felt infuriated and betrayed.

He would not allow himself to be treated so.

He began to concoct a plan, although he would later claim he was directed in his future actions by God. He may even have eventually come to believe that.

To put his plan into effect, he bought a pistol (Geary states that Guiteau made sure to get a gun with an attractive handle, as he was sure it would soon be featured in a place of honor in a fine museum) and made several aborted attempts at the assassination. He would later state that he decided not to act on those earlier occasions because of his desire not to accidentally shoot someone else, his displeasure with the weather, or the fact that Garfield's wife was with him and Guiteau didn't want to cause her needless anguish.

On the morning of July 2, 1881, he arose early, ate breakfast, and went out to assassinate the president.

When Garfield was brought back to the White House after the shooting, various doctors swarmed around and offered numerous and conflicting advice on methods to save his life. Medical practice at the time did not include the hygienic practices of today, and so doctors put their unwashed and ungloved fingers (as well as various unsterilized instruments) into the wound in the president's back in an attempt to find and dig out the bullet. These doctors consequently caused numerous infections and complications that would ultimately be the reason for Garfield's death in mid-September.

As the president lingered in agony for weeks, Guiteau's imprisonment did nothing to dispel his delusion that he had done something noble and would be applauded by everyone. As reproduced on the Lauinger Library's Web site, in the days before the shooting he had drafted a letter that he presumed would be widely published after the deed and would result in his idolization:

To the American People: I conceived the idea of removing the President four weeks ago. Not a soul knew of my purpose. I conceived the idea myself and kept it to myself. I read the newspapers carefully for and against the Administration, and gradually the conviction settled on me that the President's removal was a political necessity, because he proved a traitor to the men that made him, and thereby imperiled the life of the Republic. This is not murder. It is a political necessity.

He also wrote to famed General William T. Sherman in a tone one would use to write to a trusted confidante:

I have just shot the President. I shot him several times as I wished him to go as easily as possible. His death was a political necessity. I am a lawyer, theologian, and politician. I am going to the jail. Please order out your troops and take possession of the jail at once.

According to Lauinger Library's Web site, Sherman passed along the letter saying "I don't know the writer. Never heard of or saw him to my knowledge."

When Garfield died on September 19, Guiteau was charged with murder and his trial began November 14, 1881. It could charitably be called a circus and would last for more than six months.

Officially, Guiteau's defense would be headed up by his brother-in-law (Frances's husband), George Scoville -- but Guiteau was quite vocal in his dissatisfaction with Scoville and argued loudly with many aspects of Scoville's defense strategy, especially when any attempt to use an insanity defense was put into play. He also chose to speak directly to the judge, witnesses, and spectators whenever he pleased -- often loudly contradicting testimony or objecting to lines of questioning.

In spite of waves of hate mail flowing into the jail, Guiteau believed his actions had been commanded by God and he would be freed and given the proper praise for his heroic action, once addressing the courtroom spectators:

I (have) had plenty of visitors, high-toned, middle-toned and low-toned people...everybody was glad to see me...they all expressed the opinion without one dissenting voice that I be acquitted.

He would call on his mythical supporters to add to the rapidly shrinking funds that were paying for his defense, even having the audacity to place himself on equal footing with the woman he'd recently made a widow:

(I) desire to invite my friends throughout the nation to send me money. (People have given) Mrs. Garfield $200,000...a splendid thing, a noble thing. Now I want them to give me some money.

Throughout the trial, Guiteau insisted (and technically was correct) that Garfield had died from complications resulting from mistreatment at the hands of the doctors. He was equally adamant that he could not be held accountable, anyway, since he had been acting for God.

He continually berated Scoville whenever the lawyer didn't go along with his wishes. The History House quotes just a few of Guiteau's tantrums:

Get off the case, you consummate ass!

I would rather have some ten-year-old boy try this case than you!

You have compromised my case in every move you make!

After months of testimony and countless outbursts from the defendant, the jury adjourned and promptly found him guilty.

The Lauinger Library's Web site states that despite the reports from several noted doctors who were convinced Guiteau was insane -- and impassioned pleas from his family -- he was executed on June 30, 1882.

He enlightened the hangman and crowds around the scaffold with a muddled and peculiar poem he had written for the occasion -- a final gift for the people who should have revered him.

But the adulation he expected never came, and his name is largely forgotten today.

Shortly after his death he did become the subject of a folk ballad (one of several known versions is below), but it is infrequently performed and rarely recorded, leaving the man who believed himself destined for Great Things to become a footnote in popular history, at best.

Come all you tender Christians, wherever you may be,

And likewise pay attention to these few lines from me.

For the murder of James A. Garfield I am condemned to die,

On the thirtieth day of June, upon the scaffold high.

(Repeating Chorus):

My name is Charles Guiteau -- my name I'll never deny.

I leave my aged parents to sorrow and to die.

But little did I think, while in my youthful bloom,

I'd be going to the scaffold to meet my fatal doom.

'Twas down at the station I tried to make my escape,

But Providence being against me, it proved to be too late.

They took me off to prison while in my youthful bloom,

To be taken to the scaffold to meet my fatal doom.

I tried to play insane but found it wouldn't do,

All people were against me, for escape there was no clue.

Judge Cox, he passed my sentence, his clerk he wrote it down:

I'd be carried to the scaffold to meet my fatal doom.

My sister came to prison, to bid a last farewell.

She threw her arms around me and wept most bitterly.

She said, "My darling brother, this day you must die,

For the murder of James A. Garfield, upon the scaffold high.

James A. Garfield

20th President of the United States

http://www.jamesgarfield.org/

JAMES ABRAM GARFIELD was born in a log cabin in Orange, Cuyahoga County, Ohio on November 19, 1831, the youngest of five children. His father, Abram Garfield, was a native of New York, but of Massachusetts ancestry, descended from Edward Garfield, an English Puritan, who in 1630 was one of the founders of Watertown. His mother, Eliza Ballou, was born in New Hampshire, of a Huguenot family that fled from France to New England in 1685. Abram Garfield moved his family to Ohio in 1830, and settled in what was then known as “The Wilderness”. Abram made a prosperous beginning as a farmer and a canal construction worker in his new home, but died at the age of thirty-three after a sudden illness. Eliza Garfield brought up her young family unaided in a lonely cabin and impressed on them he high standard of moral and intellectual worth. She displayed almost heroic courage. Hers was a life of struggle and poverty, but the poverty of her home differed from that of cities or settled communities – it was the poverty of the frontier and all shared it.

James A. Garfield started school at the age of three, attending classes in a log hut and learned to read and began a habit of reading that would only end with his life. At ten years of age he was helping out his mother’s meager income by working at home or on the farm of the neighbors. Labor was play to the healthy boy and he did it cheerfully, for his mother’s hymns and songs sent her children to their tasks with a feeling that the work was honorable. By the time he was fourteen, young Garfield was fairly knowledgeable in arithmetic and grammar and was particularly interested in the facts of American history, having eagerly gathered information from the meager treaties that circulated in that remote section of Ohio. In fact, he read and reread every book the scanty libraries of his part of the wilderness supplied, and many he learned by heart. The tales of the sea especially thrilled Garfield and a love for adventure took over him. In 1848, at the age of seventeen, Garfield went to Cleveland and planned to work as a sailor on board a lake schooner. He soon realized that the life was not the romance he had envisioned. He did not want to return home without adventure and without money, so he drove for a few months for a boat on the Ohio canal. Little is known of this experience except that young Garfield secured a promotion from the towpath to the boat, and a story that he was strong enough and brave enough to hold his own against his fellow workers, who were naturally a rough group.

In 1849, Garfield’s mother persuaded him to enter Geauga Academy in Chester, Ohio, which was about ten miles from his home. During his vacations he learned and practiced carpentry and helped at harvest, he taught and did anything and everything to get money to pay for his schooling. After his first term, he needed no aid from home, he had reached the point were he was self-sufficient. While at Chester, he met a Miss Lucretia Rudolph, his future wife. He was attracted at first by her interest in the same intellectual pursuits, and he quickly discovered sympathy in other tastes and a congeniality of disposition, which paved the way for the one great love of his life. He was himself attractive at this time, and he exhibited many signs of intellectual superiority and was physically a splendid specimen of vigorous young manhood. He studied hard, worked hard, cheerfully ready for any emergency, even that of the prize ring; for, finding it a necessity, he one day thrashed the bully of the school in a stand up fight. His nature, always religious, was at this period profoundly stirred in that direction. He was converted under the instructions of a Campbellite preacher, was baptized and received into that denomination. They called themselves “The Disciples” condemned all doctrines and forms and sought to direct their lives by the Scriptures, simply interpreted, as any plain man would read them. This sanction to independent thinking given by religion itself had great influence in this young man that kept his earnest nature out of the ruts of bigotry. From this moment, his zeal to get the best education heightened and he began to take wider views, to look beyond the present and into the future.

In 1851, after finishing his studied in Chester, he entered the principal educational institution of the Campbellites, Hiram Eclectic Institute (later Hiram College). He was not a very quick study, but he was determined and he soon had an excellent knowledge of Latin and was fairly adept in algebra, natural philosophy and botany. He read with appreciation, but his superiority was easily recognized in the debating societies of the college, where he was industrious and outstanding. Living at Hiram was inexpensive, and he easily made his expenses by teaching in the English departments, and also gave instruction in the ancient languages. After three years, Garfield was well prepared to enter the junior class of any eastern college, and he had saved $350 toward the expense. He hesitated between Yale, Brown and Williams colleges, finally choosing Williams on the kindly promise of encouragement sent him by its president, Mark Hopkins. It was natural to expect Garfield would choose Bethany College, in West Virginia, an institution largely controlled and patronized by the Campbellites. Garfield himself felt the need to explain his choice, giving the reasons that Bethany was too friendly in opinion to slavery, that Bethany was not as extended as were the New England colleges; and most significant of all – that he had both by birth and by association, held a strong bias toward the religious views of Bethany, he ought to examine other faiths.

James A. Garfield entered Williams in the autumn of 1854 and graduated with the highest honors in the class of 1856. His classmates joined with President Hopkins in testifying that in college he was warm hearted, large minded and possessed a great earnestness of purpose and a singular poise of judgment. But outside of these and other like qualities such as industry, perseverance, courage, modesty, unassuming manners, and conscientiousness, Garfield hand exhibited up to this time no signs of the superiority that was to make him a conspicuous figure. The effects of twenty-five years of the most varied discipline, cheerfully accepted and faithfully used, begin to show themselves and to give to history one of its most striking examples of what education – the education of books and circumstances – can accomplish. Garfield was not born, but made; and he made himself by persistent, strenuous, conscientious study and work. In the next six years, he was a college president, a state senator, a major general in the National army, and a representative-elect to the National congress. No other American president had received so many rapid and varied promotions.

On his return to Ohio after his graduation in 1856, he resumed his place as a teacher of Latin and Greek at Hiram, and the next year (1857) being then only twenty-six years of age, he was made its president. He was a successful officer, and ambitious beyond his allotted tasks. He discussed with his interested classes almost every subject of current interest in science, religion, education and art. The story spread, and his influence with it; he became an intellectual and moral force in the Western Reserve. His influence was greatest, however, over the young. They became infected with his thirst of knowledge, his sympathy, his manliness and his veneration for the truth when it was found. As an educator, he was, and always would have been eminently successful; he had the knowledge, the art to impart it, and the personal magnetism that impressed his love for it upon his pupils. His intellectual activity at this time was intense. The laws of his church permitted him to preach, and he used the permission. He also pursued the study of law, entering his name, in 1858 as a student in a law office in Cleveland, but studied in Hiram.

On November 11, 1858, James A. Garfield married Lucretia Rudolph, his fellow student at Geauga Academy. The couple had seven children: Eliza A. Garfield (1860-63); Harry A. Garfield (1863-1942); James R. Garfield (1865-1950); Mary Garfield (1867-1947); Irvin M. Garfield (1870-1951); Abram Garfield (1872-1958); and Edward Garfield (1874-76).

To one ignorant of the slow development of Garfield in all directions, it would seem incredible that he now for the first time began to show any noticeable interest in politics. He seems never to have even voted before the autumn of 1856. No one who knew the man could doubt that he would then cast his vote for the first Republican candidate for the presidency, John Fremont. As moral questions entered more and more into politics, Garfield’s interest grew apace, and he sought frequent occasions to discuss these questions in debate. In advocating the cause of freedom against slavery, he showed for the first time a skill in discussion that afterward bore good fruit in the House of Representatives. Without solicitation or thought on his part, in 1859, he was sent to represent the counties of Summit and Portage in the senate of Ohio. Again in this new field his versatility and industry are outstanding. He makes exhaustive investigations and reports on such widely different topics as geology, education, finance and parliamentary law. Always looking to the future, and apprehensive that the impending contest might leave the halls of legislation and seek the arbitrage of war, he gave special study to the militia system of his state and the best methods of equipping and disciplining it.

The Civil War came, and Garfield, who had been a farmer, carpenter, student, teacher, lawyer, preacher and legislator, was to show himself an excellent soldier. In August 1861, Governor William Dennison commissioned him lieutenant colonel in the 42nd regiment of Ohio volunteers. The men were his old pupils at Hiram College, whom he had persuaded to enlist. Promoted to the command of this regiment, he drilled it into military efficiency while awaiting orders to the front. In December, 1861, he reported to General Buell in Louisville, Kentucky. General Buell was so impressed by the soldierly condition of the regiment that he gave Colonel Garfield a brigade, and assigned him the difficult task of driving the confederate general Humphrey Marshall from eastern Kentucky. Buell’s confidence was such that he allowed the young soldier to lay his own plans, though on their success hung the fate of Kentucky. The undertaking itself was difficult. General Marshall had 5,000 men, while Garfield had only half that number, and must march through a state where the majority of the people were hostile, to attack an enemy strongly entrenched in a mountainous country. Garfield, not daunted at all, concentrated his little force and moved it with such rapidity, sometimes here and sometimes there, that General Marshall was deceived by his moves and still more by false reports which were skillfully prepared for him. Marshall abandoned his position and many of his supplies at Paintville, and was caught in retreat by Garfield, who charged the full force of the enemy and maintained a hand-to-hand fight with it for five hours. The enemy had 5,000 men and 12 cannons; Garfield had no artillery and but 1,100 men. Garfield held his own until reinforced by Generals Graner and Sheldon, when Marshall gave way, leaving Garfield the victor at Middle Creek, January 10, 1862, one of the most important of the minor battles of the war. Shortly afterward the Confederates lost the state of Kentucky. In recognition of his service, President Lincoln made the young Garfield a Brigadier General dating his commission from the battle of Middle Creek. During Garfield’s campaign of the Big Sandy, he was engaged in breaking up some scattered Confederate encampments, his supplies gave out and he was faced with starvation. Going himself to the Ohio River, Garfield seized a steamer, loaded it with provisions and on the refusal of any pilot to undertake a perilous voyage (the river was high and running very fast), he took the helm and for forty-eight hours piloted the craft through the dangerous channel. In order to surprise Marshall who was then entrenched in Cumberland Gap, Garfield marched his soldiers 100 miles in four days through a blinding snowstorm. Returning to Louisville, he found that Buell was away, and overtook him at Columbia Tennessee and was assigned to the command of the 20th Brigade. He reached Shiloh in time to take part in the second day’s fight, was engaged in all the operation in front of Corinth, and in June, 1862, rebuilt the bridges on the Memphis and Charleston railroad, and exhibited noticeable engineering skill in repairing the fortifications of Huntsville. The unhealthful ness of this region overcame Garfield, and on July 30, 1862, he returned to Hiram, under leave of absence, where he lay ill for two months. After regaining his strength, Garfield reported to Washington and was ordered to court-martial duty, and gained a very respectful reputation in this practice. Garfield was retuned to duty under General Rosencrans who made him his chief of staff, with responsibilities beyond those usually given to this office. After the Union loss at the Battle of Chickamauga, Garfield volunteered to take news of the defeat to General George H. Thomas, who held the left of the line. It was a bold ride, under constant fire, but he reached Thomas and gave the information that saved the Army of the Cumberland. For this action he was made a major general on September 19, 1863, promoted for gallantry on a field that was lost. With a future military career so bright before him, Garfield, always unselfish, yielded his own ambition to a request by Mr. Lincoln that he hasten to Washington to sit in Congress. Garfield had been chosen fifteen months before as the successor of Joshua R. Giddings.

James A. Garfield was thirty-two years old when he entered congress. In December 1863, he started his first term as a representative for his home district. He was reelected for eight successive terms to the same office. His military reputation had preceded him and secured for him a place in the Committee on Military Affairs, then the most important in congress. Garfield was a loyal Republican. He favored a policy of “hard money” the principle that all paper money issued by the government should be secured by gold or silver. After the Civil War he sided with the radical faction of the Republican Party, supporting seizure of the property of those who had served the Confederacy and demanding voting rights for blacks.

In 1865, Garfield, at his own request, was changed from the Committee on Military Affairs to the influential Ways and Means Committee. He soon became a power in his party. In 1876, James G. Blaine of Massachusetts resigned his seat to serve in the Senate. James A. Garfield assumed the Republican leadership in the House. During his rise to power, Garfield was connected to two incidents that tarnished his record, one involving an alleged bribe to delay a congressional investigation of Credit Mobilier Company, which had made illegal profits fro government contracts. The other involved accepting fees from a company trying to obtain a paving contract for Washington, D.C. Garfield denied all charges but remained his own harshest critic that he had not shown his usual cautiousness in avoiding any connection with any matter which could come up for congressional review. His Ohio constituents knew both scandals in 1874, but he was reelected for another term.

James A. Garfield was elected the United States Senator from Ohio in 1880. Before his term began, he became involved in the presidential campaign of 1880. He supported Secretary of the Treasury, John Sherman, another Ohioan, and was head of his state’s delegation and manager of the Sherman campaign at the Republican national convention. He worked hard to win convention delegates for Sherman. He was chairman of the rules committee and he persuaded the convention to permit delegates to vote individually rather than in state blocks. This system freed many delegates from party dictated support, however, no candidate was able to muster a majority. Garfield addressed the convention on behalf of Sherman, but he spoke for 15 minutes before he mentioned Sherman’s name. Many suspected that Garfield was placing himself in nomination and he probably won more cheers for himself than for his candidate. There is no evidence to suggest that he was disloyal to Sherman but finally on the 36th ballot on the convention’s sixty day, Garfield himself was nominated for president. Chester A. Arthur, a former customs collector of the Port of New York was nominated for vice president.

Garfield won the election but he did not have a majority of the popular vote. He received 214 electoral votes to Democrat Winfield S. Hancock’s 155, however, his electoral margin came mainly for Northern states as he received 4,454,416 popular votes compared to Hancock’s 4,444,952.

After the election Garfield surrendered his Senate seat to which he had been elected and he resigned from the House. He was inaugurated on March 4, 1881. Once in office, Garfield took a stand against political corruption. In May he won a showdown with a powerful New York Senator, Roscoe Conkling, with his choice of Conkling’s rival to head the New York Customs House. The early summer came and peace and happiness and the growing strength and popularity of his administration cheered Garfield’s heart.

On the morning of July 2, 1881, the president was setting out on a trip to New England. He was passing through the waiting room of the Baltimore and Potomac railroad depot at nine o’clock in the morning with Mr. James G. Blaine, his close friend. Charles Guiteau, a lawyer who’s application to be the U. S. ambassador to France was denied, fired two shots at President Garfield. One bullet grazed the President’s arm but the other one had entered his back, fractured a rib and lodged itself somewhere inside Garfield’s body. Guiteau, a religious fanatic stated that he shot Garfield in order “to unite the Republican Party and save the Republic”. Guiteau readily gave himself up after the shooting – he reportedly had arranged to have a hansom cab wait for him outside to take him to jail because he was afraid that an angry mob would form and lynch him. The Washington police arrested him.

Garfield, who never lost consciousness, was taken to the White House. Under the highest medical skill of the day, Garfield lingered between life and death for more than ten weeks. There were two methods of treatment at the time for bullet wounds. First, if the bullet had penetrated an organ, it would mean certain death without surgery to remove it. Second if the bullet hadn’t penetrated an organ it would be better to delay surgery until the condition of the patient stabilized. The first doctor to see the President, Dr. Willard Bliss stuck his finger into the wound (unsterilized) trying to probe and find the bullet. He never found it but the passageway that he dug through the President later confused physicians as to the bullet’s path. They concluded that the bullet had penetrated the liver and surgery would be of no help. They were wrong. In an effort to find the bullet, Alexander Graham Bell devised a crude metal detector. On July 26, Bell and his assistant, Tainter and Simon Newcomb (who originally had the idea of the metal detector) made their first attempt to locate the bullet in Garfield’s body. There were also five White House doctors and several aides present for the experiment. Garfield expressed fear of being electrocuted and Bell reassured him. The results of the experiment were inconclusive as there was a hum no matter where the wand was placed on the president’s body. Bell was unaware that the White House was one of the few that had a coil spring mattress that had just been invented. Very few people had even heard of them. If Bell had moved Garfield off the bed, their apparatus would have detected where the bullet was and likely, knowing this, the surgeons could have saved James A. Garfield’s life.

In the end, the doctors had taken a three-inch wound and turned it into a twenty-inch gouge that was massively infected. On September 15, 1881, symptoms of blood poisoning appeared. Garfield lingered until September 19, 1881 when, after a few hours of unconsciousness, he died.

As the last of the log cabin Presidents, James A. Garfield attacked political corruption and won back for the Presidency a measure of prestige it had lost during the Reconstruction period.

http://www.whitehouse.gov/history/presidents/jg20.html

He was born in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, in 1831. Fatherless at two, he later drove canal boat teams, somehow earning enough money for an education. He was graduated from Williams College in Massachusetts in 1856, and he returned to the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (later Hiram College) in Ohio as a classics professor. Within a year he was made its president.

Garfield was elected to the Ohio Senate in 1859 as a Republican. During the secession crisis, he advocated coercing the seceding states back into the Union.

In 1862, when Union military victories had been few, he successfully led a brigade at Middle Creek, Kentucky, against Confederate troops. At 31, Garfield became a brigadier general, two years later a major general of volunteers.

Meanwhile, in 1862, Ohioans elected him to Congress. President Lincoln persuaded him to resign his commission: It was easier to find major generals than to obtain effective Republicans for Congress. Garfield repeatedly won re-election for 18 years, and became the leading Republican in the House.

At the 1880 Republican Convention, Garfield failed to win the Presidential nomination for his friend John Sherman. Finally, on the 36th ballot, Garfield himself became the "dark horse" nominee.

By a margin of only 10,000 popular votes, Garfield defeated the Democratic nominee, Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock.

As President, Garfield strengthened Federal authority over the New York Customs House, stronghold of Senator Roscoe Conkling, who was leader of the Stalwart Republicans and dispenser of patronage in New York. When Garfield submitted to the Senate a list of appointments including many of Conkling's friends, he named Conkling's arch-rival William H. Robertson to run the Customs House. Conkling contested the nomination, tried to persuade the Senate to block it, and appealed to the Republican caucus to compel its withdrawal.

But Garfield would not submit: "This...will settle the question whether the President is registering clerk of the Senate or the Executive of the United States.... shall the principal port of entry ... be under the control of the administration or under the local control of a factional senator."

Conkling maneuvered to have the Senate confirm Garfield's uncontested nominations and adjourn without acting on Robertson. Garfield countered by withdrawing all nominations except Robertson's; the Senators would have to confirm him or sacrifice all the appointments of Conkling's friends.

In a final desperate move, Conkling and his fellow-Senator from New York resigned, confident that their legislature would vindicate their stand and re-elect them. Instead, the legislature elected two other men; the Senate confirmed Robertson. Garfield's victory was complete.

In foreign affairs, Garfield's Secretary of State invited all American republics to a conference to meet in Washington in 1882. But the conference never took place. On July 2, 1881, in a Washington railroad station, an embittered attorney who had sought a consular post shot the President.

Mortally wounded, Garfield lay in the White House for weeks. Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, tried unsuccessfully to find the bullet with an induction-balance electrical device which he had designed. On September 6, Garfield was taken to the New Jersey seaside. For a few days he seemed to be recuperating, but on September 19, 1881, he died from an infection and internal hemorrhage.

Impact and Legacy

http://millercenter.virginia.edu/Ampres/essays/garfield/biography/9?PHPSESSID=cd53cc30f9363ce4119851f74853beda

Murdered within months of his inauguration, Garfield served as President too briefly for him to have left much of an impact. Still, his legacy is far more ambiguous than most people realize. His replacement of Merritt shows him not only lacking judgment but acting as a spoilsman himself. His secretary of state, James G. Blaine, conducted foreign policy in, at best, an offhand manner, adding to the burdens of his successor, Chester A. Arthur. Nevertheless, Garfield appeared to be increasingly dependent upon Blaine as his short-lived presidency emerged. Since Garfield was passionately devoted to hard money and a laissez-faire economy, it is doubtful whether he could have really coped with the recession that began in 1881. He might have advanced the cause of civil rights, but without again stationing federal troops in the South, his options were limited.

For his reputation, it might have been just as well that he died when he did. He died in the prime of his life, still politically untested. The times did not demand a President in the heroic mold, and Garfield could therefore be remembered as a martyr above all else, as one who truly gave his life for his nation.

Presidents of the United States (1789-2007)

![Brotherhood" (2006) [TV-Series]](http://photos1.blogger.com/x/blogger2/1421/379621144723082/211/z/425926/gse_multipart33129.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment