Computers are still an important part of its mix, but these days music-related products are at the top of Apple's playlist. The company scored a runaway hit with its digital music players (iPod) and online music store (iTunes). Apple's desktop and laptop computers -- all of which feature its OS X operating system -- include its Mac mini, iMac, and MacBook for the consumer and education markets, and more powerful Power Mac and MacBook Pro for high-end consumers and professionals involved in design and publishing. Other products include servers (Xserve), wireless networking equipment (Airport), and publishing and multimedia software. The company's FileMaker subsidiary makes database software.

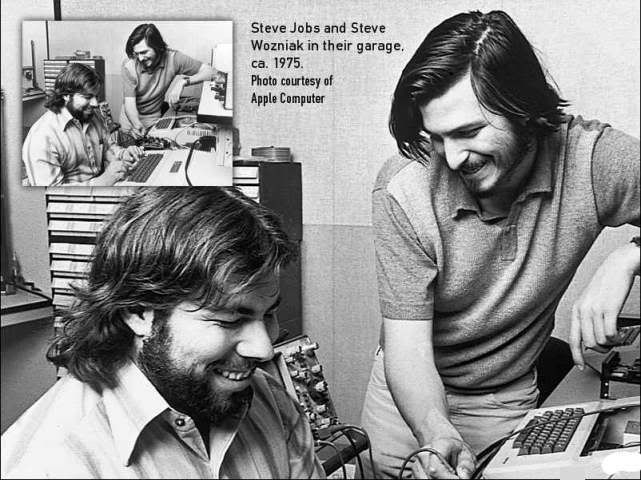

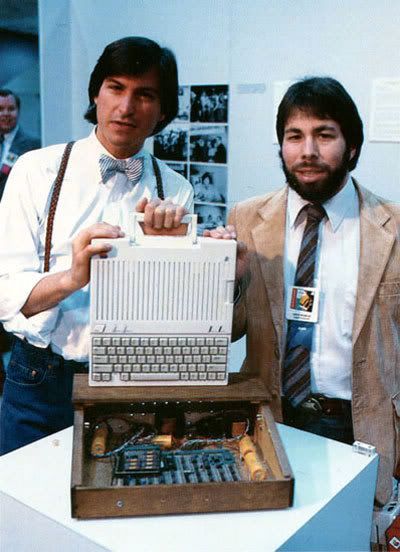

A manufacturer of computers and consumer electronics, Apple is the industry's most fabled story. Founded in a garage by Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs and guided by Mike Markkula, Apple blazed the trails for the personal computer industry. Apple was formed on April Fool's Day in 1976. After introducing the Apple I at the Palo Alto Homebrew Computer Club, 10 retail stores were selling them by the end of the year.

In 1977, the Apple II was introduced, a fully-assembled computer with 4K RAM for $1,298. Its open architecture encouraged third-party vendors to build plug-in hardware enhancements. This, plus sound and color graphics, caused Apple IIs to become the most widely used computer in the home and classroom. They were also used in business primarily for the innovative VisiCalc software that was launched on it.

In 1983, Apple introduced the Lisa, the forerunner of the Macintosh. Lisa was aimed at the corporate market, but was soon dropped in favor of the Mac. As a graphics-based machine, the Mac was successful as a low-cost desktop publishing system. Although praised for its ease of use, its slow speed, small monochrome screen and closed architecture didn't excite corporate buyers. But, things were to change.

In 1987, the Mac II offered higher speed, larger screens in color and traditional cabinetry that accepted third-party add-in cards. Numerous models were offered and widely accepted. In 1991, Apple surprised the industry by announcing an alliance with IBM to form several companies that would develop hardware and software together. All these eventually folded back into Apple and IBM, but the major product of the alliance was the PowerPC chip (see Apple-IBM alliance). In 1994, Apple came out with its first PowerPC-based PowerMacs, which proved very popular. Its PowerBook laptops were an instant success, and all subsequent models departed from the original Motorola 680x0 architecture to the PowerPC.

Apple has stood alone in a sea of IBM and IBM-compatible PCs for more than a decade and a half. It has watched its graphical interface copied more with each incarnation of Windows and watched its market share drop simultaneously. In late 1994, Apple began to license its OS to system vendors in order to create a Macintosh clone industry, which pundits had been suggesting for years. However, a couple of years later, that was discontinued.

In 1997, Apple acquired NeXT Computer, which brought Steve Jobs back to the company he founded and gave it a raft of object-oriented development tools, parts of which filtered down into the Mac OS X operating system.

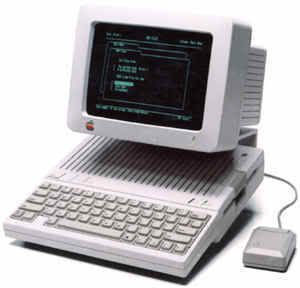

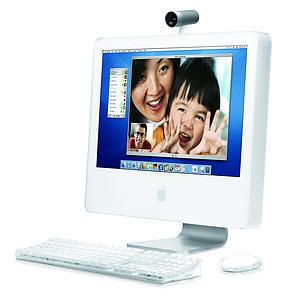

In 1998, Apple introduced the iMac, a low-priced Internet-ready Mac that was the first personal computer without a floppy disk. Self-contained in one unit like the original Mac, Apple sold 800,000 iMacs in a year, making it the fastest-selling computer in its history. Apple's subsequent models, including the G4 Cube and Titanium portable, were in a class by themselves. Apple continues to offer attractive alternatives to the Windows-based PC.

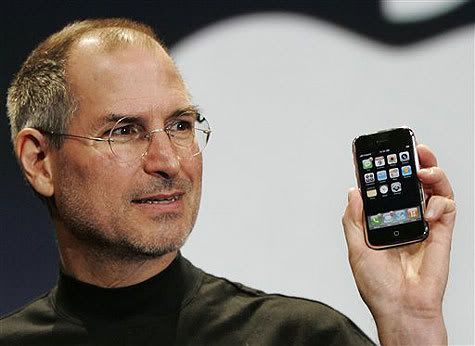

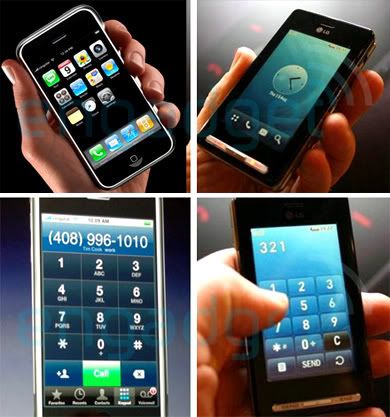

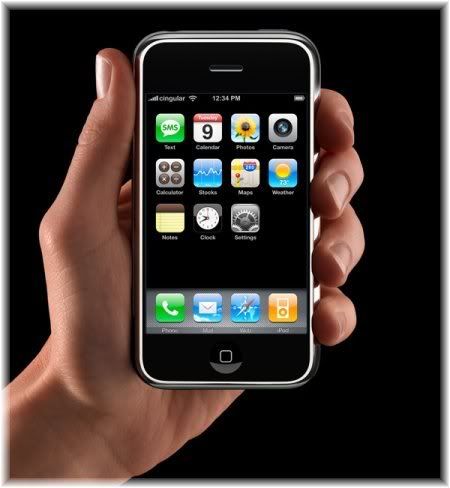

In 2001, Apple launched the iPod, one of the most successful consumer electonics products in history. Setting the bar for portable music players, every competing product is measured against the iPod's ease of use and capabilities. In 2007, Apple announced the iPhone, a combination iPod, phone and Internet appliance that is available in the U.S. exclusively from AT&T (Cingular) for two years.

http://www.answers.com/topic/apple-computer-inc?cat=biz-fin

Apple Inc. (NASDAQ: AAPL, LSE: ACP, FWB: APC) (formerly Apple Computer, Inc.) is an American multinational corporation with a focus on designing and manufacturing consumer electronics and closely-related software products. Headquartered in Cupertino, California, Apple develops, sells, and supports a series of personal computers, portable media players, computer software, and computer hardware accessories; Apple is also currently involved in the creation of new technology concepts, such as the iPhone, Apple TV, and many features of its new, upcoming operating system, Mac OS X "Leopard". Apple also operates an online store for hardware and software purchases, as well as the iTunes Store, a comprehensive offering of digital downloadable music, audiobooks, games, music videos, TV shows, and movies. The company's best-known hardware products include the Mac line of personal computers and related peripherals, the iPod line of portable media players, and the iPhone. Apple's best known software products include the Mac OS operating system and the iLife software suite, a bundle of integrated amateur creative software products. (Both Mac OS and iLife are included on all Macs sold.) Additionally, Apple is also a major provider of professional (as well as "prosumer") audio- and film-industry software products. Apple's professional and "prosumer" applications, which run primarily on Mac computers, include Final Cut Pro, Logic Audio, Final Cut Studio, and related industry tools.

Apple had worldwide annual sales in its fiscal year 2006 (ending September 30, 2006) of US$19.3 billion.[1]

The company, incorporated January 3, 1977[3], was known as Apple Computer, Inc. for its first 30 years. On January 9, 2007, the company dropped "Computer" from its corporate name to reflect that Apple, once best known for its computer products, now offers a broader array of consumer electronics products.[4] The name change, which followed Apple's announcement of its new iPhone smartphone and Apple TV digital video system, is representative of the company's ongoing expansion into the consumer electronics market in addition to its traditional focus on personal computers.[5]

Apple also operates 180 (as of June 2007) retail stores in the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, Canada, and Italy.[6] The stores carry most of Apple's products as well as many third-party products and offer on-site support and repair for Apple hardware and software. Apple employs over 20,000 permanent and temporary workers worldwide.[7]

For a variety of reasons, ranging from its philosophy of comprehensive aesthetic design to its countercultural, even indie roots, as well as their advertising campaigns, Apple has engendered a distinct reputation in the consumer electronics industry and has cultivated a customer base that is unusually devoted to the company and its brand

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apple_Computer

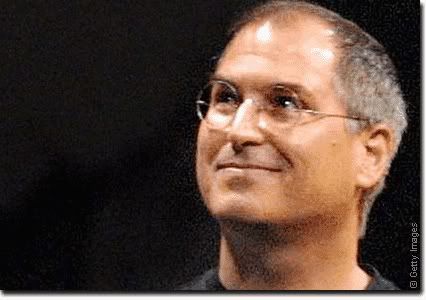

Steve Jobs

Steven Paul Jobs (born February 24, 1955) is the co-founder and CEO of Apple and was the CEO of Pixar until its acquisition by Disney.[2] He is currently the largest Disney shareholder [7] and a member of Disney's Board of Directors. He is considered a leading figure in both the computer and entertainment industries.[8]

Jobs' history in business has contributed greatly to the mythos of the quirky, individualistic Silicon Valley entrepreneur, emphasizing the importance of design while understanding the crucial role aesthetics play in public appeal. His work driving forward the development of products that are both functional and elegant has earned him a devoted following.[9]

Together with Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak, Jobs helped popularize the personal computer in the late '70s. In the early '80s, still at Apple, Jobs was among the first to see the commercial potential of the mouse-driven GUI.[10] After losing a power struggle with the board of directors in 1985, Jobs was fired from Apple Computer and founded NeXT, a computer platform development company specializing in the higher education and business markets. NeXT's subsequent 1997 buyout by Apple brought Jobs back to the company he co-founded, and he has served as its chief executive officer since his return.

Steve Jobs Stanford Commencement Speech 2005

Steve Jobs on CNBC

Apple Timeline

http://www.mapreport.com/na/west/ba/news/cities/apple.html

History of Apple

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Apple_Inc.

1984 Apple Computer inc. We are apple

Time line: Three decades of Apple innovation

http://news.com.com/2009-1041-6054524.html

The Apple Museum

http://applemuseum.bott.org/

1984 Apple's Macintosh Commercial

Apple Computer 30th Anniversary

Apple Computer Timeline

http://www.mac-net.com/1551083.page

2005 Apple ships Mac Mini that comes with Mini but with 1.25 GHz PowerPC G4 processor but without a display and in a tiny form factor. Apple introduces 4 button mouse with a small 360 degree scroll trackball. Mac OS X v10.4 (Tiger) available. iPod shuffle was sold.

2004 An iPod year for Apple see the introduction of iPod Photo and iPod Mini. iMac G5 with 1.8GHz PowerPC 970 (aka G5) Processor.

2003 Apple Safari browser released. iTune launch and offer music at 99cents to download each song. Mac OS X v10.3 (Panther) available

2002 iMac comes with its 10.5" base, 15" flat panel, 800 MHz G4 Processor and DVD Burner. eMac was announced as education only model. Mac OS X v10.2 (Jaguar) available.

2001 Mac OS X ships. Apple redesign iBook and it now comes only in a white box with rounded edges - 500 MHz, prices start at $1,299. Mac OS X 10.0 (Cheetah) and later Mac OS X 10.1 (puma) was released, noted for improved speed. iPod introduced.

2000 Power Mac G4 Cube with 450 MHz PPC 7400 (aka G4) runs on Mac OS 9.0 in a 7.7" square and 10" tall casing announced.

1999 Mac OS X Server ships. Apple ships multi-coloured (orange, green, gray, and blue) iBook.

1998 iMac with 233 MHz PPC 750 (aka G3) runs Mac OS 8.1, garish (some say "girlie") colours and housed in a transparent case was introduced. Apple announces PowerBook G3 Series. Apple phases out Newton.

1997 Steve Jobs becomes an advisor and interim CEO at Apple Computer. Mac OS 8 ships for all 68040-based and later Macs.

1996 Apple buys NeXT.

1995 One-millionth Power Macintosh produced.

1994 Power Macintosh line introduced.

1993 Mac LC III introduced. Apple II line discontinued. System 7.5 introduced. First Apple Newton ships. John Sculley resigned from Apple.

1992 System 7.1 introduced. Mac LC II replace Mac LC. Mac Classic II is reintroduced.

1991 Apple introduces System 7.0 with QuickTime. PowerBook 100 introduced.

1990 Mac LC with 32-bit CPU on a 16-bit data bus was introduced with a new low price point of $2,500.

1989 Mac SE/30 introduced at $4,369. Mac IIci with 32-bit clean Mac was introduced.

1988 Apple introduces CD-ROM player for Mac. Macintosh System 6.0 was introduced. Apple IIc+ introduced in September at $1,099.

1987 Apple Mac II (3/87-1/90), first 68020-based Mac , introduced at $3,898. Macintosh System 4.0 (March) has improved Chooser, Control Panel and networking AppleShare. One-millionth Mac produced.

1986 Macintosh System 3.0 which featured disk cache and HFS, which allows nested folders. Japanese and Arabic versions of MacOS introduced. Apple IIGS introduced in September at $999.

1985 Steve Wozniak leaves Apple followed later by Steve Jobs. Lisa 2 is renamed Macintosh XL and all other Lisa models discontinued. Macintosh System 2.0 introduces New Folder command and viewing by small icon or as a list.

1984 Legendary ad appears during Super Bowl with the introduction of Apple Macintosh with 8 MHz Motorola 68000 CPU with 9" B&W sreen and 400KB floppy drive and sells for $2,495. Apple IIc introduced at $1,295. Apple introduced Lisa 2.

1983 John Sculley becomes Apple´s president and CEO and Apple Lisa was introduced with 5 MHz 68000 CPU, 860k 5.25" floppy, 12" b&w screen, detached keyboard, and mouse for $9,995. Apple IIe introduced in January at $1,395. One-millionth Apple II produced.

1982 Apple takes legal action to stops flow of illegal Apple clones.

1981 Apple introduces ProFile a 5 MB hard drive for Apple III and by now have over 300,000 Apple II users.

1980 Apple goes public with 4.6 million shares and introduces Apple III for $3,495.

1979 Apple II Plus introduced with 48 KB RAM for $1,195 which targets the education market.

1978 Apple moves into new corporate headquarters and introduces 5.25" floppy drive, licenses BASIC from Microsoft and with Microsoft SoftCard lets Apple II use CP / M.

1977 Apple moves out of Steve Jobs´ garage and Apple II introduced with 4 KB RAM for $1,298.

1976 April Fools Day ´76, Apple Computer incorporated by Steve Wozniak (ex Hewlett-Packard) and Steve Jobs (ex Atari) working in in Steve Jobs´ garage and launched Apple I Computer was based on the MOStek 6502 chip and sold as a computer kit with only the circuit board and without a case for $666.66.

iPhone

Conan - iPhone Commercial

Apple iPhone: ALL DEMOS IN ONE!

Apple's IPhone Sells Out at Most AT&T Stores, Swamping Network

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601087&sid=aUIjMF2enOFY&refer=home

Apple Inc.'s U.S. debut of the iPhone drew thousands of shoppers over the weekend, emptying most of AT&T Inc.'s inventory and causing network glitches as the flood of customers began activating the device.

Shoppers snapped up as many as 200,000 iPhones the first day after the device went on sale June 29, according to Global Equities Research. While it was still available at all 164 Apple stores yesterday, AT&T said most of its 1,800 stores no longer had the phone in stock. AT&T is the only mobile-phone service that works with the iPhone.

``A lot of our stores have sold out,'' said Mark Siegel, a spokesman for San Antonio-based AT&T, the largest U.S. wireless service. ``We're restoring our inventory as fast as we can.''

The sales met the expectations of most analysts, giving Apple a foothold in the mobile-phone industry. Chief Executive Officer Steve Jobs is counting on the device to become Apple's third major source of revenue, alongside the iPod media player and the Macintosh computer. The iPhone combines a Web-surfing phone with the iPod.

Some buyers had problems activating the phones because of the large number signing up at the same time, Siegel said. There also were delays switching customers from other carriers.

Wozniak's Test

``Some of my friends are having activation difficulties,'' Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak, who got in line at 4 a.m. on June 29 to buy his iPhone, said in an e-mail interview.

He successfully activated his phone and said he's impressed with the software and how the device serves up Web pages. ``I was going to only use the iPhone as a test phone at first, but I'm ready now to make it my primary number,'' Wozniak said.

Apple stores sold an estimated 128,000 iPhones on the first day, while AT&T stores sold 72,000, said Trip Chowdhry, an analyst with San Francisco-based Global Equities.

The stores stayed open until midnight June 29. Customers could buy one phone at AT&T's stores and two at Apple's outlets. Shoppers can check Apple's Web site to see if the iPhone is in stock at any of its stores.

There's a wait of two to four weeks for customers who order the phone online from Apple, according to the site.

The iPhone comes in two versions: a 4-gigabyte model that sells for $499 and an 8-gigabyte version that costs $599. The phone requires a two-year service contract with AT&T.

Shoppers interviewed at Apple's stores in New York and California favored the 8-gigabyte model.

``For $100 more, you get double the storage,'' said engineer Rick Evans, 50, who bought his iPhone on opening night at Apple's store in Stanford, California. ``It's a no-brainer.''

Miles Barken, a shopper in Santa Monica, California, bought the 4-gigabyte version after the other model sold out.

``I was having trouble deciding between the two of them anyway,'' he said. ``This just made the decision easier for me.''

EBay Sales

The iPhone is already selling at a premium on the auction site EBay Inc., despite it still being in stock at Apple's stores. The phone has sold on EBay for an average of $978.75, the company said.

Jobs said last week that Apple tried to estimate demand and increased manufacturing. ``We've taken our best guess, but it wouldn't surprise me at all if it ain't enough,'' Jobs said in an interview with the Wall Street Journal.

Apple's investors are betting that Jobs, 52, can deliver on a pledge to capture a least 1 percent of the mobile-phone market by selling 10 million iPhones in 2008. Anticipation helped propel the company's market value above $100 billion in May for the first time.

The Cupertino, California, company's shares rose $1.48 to $122.04 on June 29 in Nasdaq Stock Market trading.

Apple's annual profit has surged to almost $2 billion from $65 million in the past five years, while sales more than tripled to about $20 billion.

Is the iPhone Worth the Wait, or Worth Waiting For?

http://www.newswise.com/articles/view/531288/

People across the country were camping out this June for a very different reason than you might think. Rather than trying to get away from modern technology, they were setting up outside of stores waiting to get their hands on it.

The release of Apple's new iPhone, the summer's must-have gadget that combines the features of a video iPod with a Web-capable camera phone, has technology geeks and seekers of the newest status symbol vying to be the first on the block to have one. But is it a good idea to hold off a little while before making this big purchase and committing to a mandatory two-year service plan?

"I recommend for people to wait for anything electronic," said David Allan, Ph.D., assistant professor of marketing at Saint Joseph's University. "But some people can't wait. They've got to have it."

Dr. Allan warned that with the first release of any new technology come glitches that can cause frustration.

One immediate problem has been the speed of the Web browser. To make the Web more widely available, Apple had to sacrifice their speedier service.

"Apple's saying that they did it because the slower network is in 13,000 cities as opposed to 165 major cities," Dr. Allan said.

Also, unlike most phones, the iPhone's memory card and battery are not easily accessible, and can only be fixed by taking it to an Apple store.

"So, when they have initial problems, there could be a big line at Apple stores," said Dr. Allan.

Still, it is unlikely that those who have their heart set on what some have come to call the "Jesus Phone" will be able to resist the allure for very long. The important thing to remember is that even though the iPhone is unlike any other device on the market, you may find yourself with an all-too-familiar technology-induced headache when problems arise.

Apple iPhone Review -- is it worth it?

A Closer Look At The iPhone

Apple's IPhone Sells for Double Costs, ISuppli Says

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601087&sid=aGfLsPKqLcTc&refer=home

Apple Inc. sells the new iPhone at more than double production costs, suggesting the new handset may be more profitable than rivals from Motorola Inc. and Nokia Oyj. The shares rose the most in six months to a record.

The most-expensive $599 model has component and manufacturing costs of $265.83, which translates into margins of more than 55 percent, according to iSuppli Corp. The research firm tore open an iPhone to identify the components in the device. Jill Tan, a spokeswoman for Apple in Hong Kong, declined to comment on the iSuppli report.

The iPhone sold out at most stores less than a week after its debut in a market led by Nokia and Motorola, the two largest handset makers. The $599 version, which costs three times as much as Motorola's Q did upon its debut, may have helped the device earn as much as $186.1 million in its opening weekend, based on estimates from Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and iSuppli.

``It had a very good start,'' said Bill Choi, an analyst with Jefferies & Co. in New York. ``They're selling it for a lot of money. On a gross margin basis, it is very profitable.''

Shares of Cupertino, California-based Apple rose $5.91, or 4.9 percent, to $127.17 at 1 p.m. New York time in Nasdaq Stock Market trading. They have jumped 50 percent this year. U.S. stock markets ended trading at 1 p.m. New York time today, and are closed tomorrow for the Independence Day holiday.

While the 55 percent figure is higher than the gross margin of some of Apple's competitors, that alone doesn't determine how profitable a product is, Choi said. Companies also have costs from marketing and research and development, and Apple still needs to sell a ``critical mass'' of iPhones to cover development costs, he said.

Margin Comparisons

Goldman Sachs said shoppers bought as many as 700,000 iPhones in the weekend after the June 29 debut in the U.S., double the brokerage's earlier projections. Piper Jaffray & Co.'s Gene Munster pegged sales at about 500,000, more than twice his original 200,000 estimate.

Research In Motion Ltd., maker of the BlackBerry, reported a gross margin of 51.8 percent in the most recent quarter. Palm Inc., maker of the Treo, had a gross margin of 38.2 percent. Motorola's mobile phones have a gross margin of less than 30 percent, Choi said.

``The margins for the iPhone are much higher than the typical handset that we've been looking at,'' iSuppli analyst Eric Pratt said in an interview today.

Apple ran out of iPhones, a combination iPod and mobile phone that offers Web and e-mail, at more than half its 164 stores yesterday. AT&T Inc., which is offering wireless service for the device, sold out of the phone in almost all its 1,800 stores, with ``just a handful'' of locations keeping the handset in stock, spokesman Mark Siegel said in an interview today.

Big Winner

ISuppli's estimate excludes costs for logistics and royalties, the El Segundo, California-based researcher said. That differs from gross margin, which is the percentage of sales minus production costs such as labor.

South Korea's Samsung Electronics Co. is the biggest supplier, accounting for 30.5 percent of component costs, by making the memory chips and processors, according to iSuppli. Infineon Technologies AG, Wolfson Microelectronics Plc, Balda AG and National Semiconductor Corp. also make parts, iSuppli said.

Apple will probably sell 4.5 million iPhones this year and more than 30 million units by 2011, according to iSuppli. Chief Executive Officer Steve Jobs said in January that the company will sell 10 million iPhones in 2008, capturing 1 percent of total handset sales worldwide.

By comparison, Nokia, the world's largest mobile-phone maker, said in April it shipped 91.1 million units in the first quarter.

The following is a table listing some of the major suppliers for the 8-gigabyte iPhone, the components and their estimated costs, according to iSuppli's report. The 4-gigabyte model retails for $499 each.

Company Components Total Costs

Infineon Digital baseband

Radio Transceiver

Power Management $15.25

National Semiconductor Display/graphics

connecting chip $1.50

Balda AG Touch screen module $27.00

Epson/Sharp/Toshiba Matsushita Touch screen display $24.50

Samsung Electronics Applications processor

NAND flash memory

DRAM chip $76.25

Wolfson Microelectronics Plc Audio codec N/A

CSR Plc Bluetooth chip $1.90

Marvell Technology Group Ltd. Wi-Fi chip $6.00

Total Bill of Materials $265.83

iPhone - from Apple

Apple calls iPhone launch a success

http://www.usatoday.com/tech/wireless/phones/2007-07-01-iphone-reax_N.htm

Apple declared opening weekend iPhone sales a success, despite activation problems reported by some of the consumers who bought the first wave of devices. Snags were confirmed by Apple and partner AT&T.

"The response to iPhone has been incredible. We are thrilled there is so much excitement," said Apple (AAPL) spokeswoman Natalie Kerris. As of late Sunday, no sales figures were released by Apple.

There was a party atmosphere at New York's Fifth Avenue Apple Store, where Greg Packer waited a week outside to claim the No. 1 spot. "Beautiful," he said after buying two iPhones.

Orders placed on Apple's website Sunday afternoon indicated that it would take two to four weeks for iPhones to ship. At the same time, Apple Stores in Chicago, Cincinnati and Albuquerque still had units in stock.

For its part, AT&T expects to fulfill new orders in three to five business days. AT&T (T) spokesman Tim Klein reported that its nearly 1,800 stores were "virtually sold out."

FIND MORE STORIES IN: Sunday | AT | Apple | Michael Gartenberg

The iPhone — combination iPod, cellphone and pocket Internet device — went on sale at 6 p.m. Friday for $499 and $599, depending on storage.

It didn't take long for sales to hit eBay (EBAY). As of 4:45 p.m. ET on Sunday, more than 2,600 iPhones sold for an average price of $775.03. The highest selling price: $12,500, for a Saturday sale through eBay's "Buy It Now" feature, which offers items at a fixed sum.

"From Apple's perspective, this is exactly the kind of supply-and-demand situation you want," says JupiterResearch analyst Michael Gartenberg, who bought one. "A little scarcity isn't a particularly bad thing, but you don't want people getting frustrated."

In Atlanta, Thom Volarath was still waiting on Sunday for his iPhone to be activated. "It's been 43 hours-plus since I've had phone service," he said in an e-mail. "I've been using my sister's (cellphone) to call AT&T."

Jackson, Miss., nursing student Jenny Springfield also encountered delays. She didn't get her $599 iPhone activated until 11 a.m. Saturday after starting the process at 7 the night before, a wait made more frustrating because AT&T deactivated her old phone.

"We have had a small percentage of customers who have had activation issues," AT&T's Klein said Sunday. "We're working on resolving those as quickly as possible."

Gartenberg thinks the hiccups are to be expected given the iPhone's complexity. "It's not a surprise that there's going to be a couple of glitches," he says. "This is a once-in-a-decade, if not once-in-a-lifetime-type event. And Apple played it perfectly from January to now."

TechTv iPod Review

Bush's iPod

Five reasons the iPod succeeded

From its interface to its DRM, Apple’s device was destined for greatness

http://playlistmag.com/features/2006/10/ipodfive/index.php

When the iPod was announced, few people outside the walls of Apple saw a product that would dominate the the portable music player market. Yet, rivals have come and gone, and the ones that remain appear content to fight over the small slice of the market Apple doesn’t own.

There is one single, overarching reason that the iPod has enjoyed the success that it has: Apple had a plan, followed through on it, and didn’t deviate from it over time. It made a simple product that to this day performs the same task that it did on the day it was announced. It might do other things today, but those are secondary. The iPod was all about the music.

But digging a bit deeper, here are five interlinked factors that helped create the iPod phenomenon, one for each year of the music player’s existence.

1. Total integration

Before Apple unleashed the iPod, no company really did a good job of integrating the player, the computer, and the software that connected the two. Companies such as Rio and Creative would ship someone else’s music software in the box with their player, or sometimes they would include their own home-grown software. Whatever you got played music on your Mac or PC just fine—getting that music from the computer to the audio player was no slam dunk.

Transferring music to a portable player in those pre-iPod days wasn’t a horrible process. But it took the iPod’s arrival to let us know just how bad things were. With the iPod, you could stick a CD into your Mac, and, 10 minutes later, it’d be on the device in your pocket—that was integration on a whole new level. And being able to automatically sync your music library by just hooking up the iPod? That was radical.

That integration was dependent upon FireWire, the conduit that moved the music from your Mac to your iPod. Using FireWire was a no-brainer for Apple, since every Mac shipped with one, but it still was a groundbreaking decision. In 2001, nearly every music player on the market used USB 1.1 to transfer your songs from your computer to your player. Talk about frustration. Moving an album, let alone four or five, was an exercise akin to watching glaciers move. You transferred music to your player before you went to bed at night, so your music would be ready to go with you on the morning commute. The iPod’s FireWire interface made that process obsolete.

But Apple didn’t get all hung up on FireWire—something the company definitely would have done a decade earlier. When the majority of shipping Macs and PCs featured speedy USB 2.0 ports as standard equipment, Apple brought the iPod right along with the trend. FireWire still had a place, but Apple smartly chose to use the technology with a wider adoption.

My colleague Dan Frakes says it best: “No other player made it so easy to get music (via CDs, online services, or, let’s face it, file sharing), and then get that music organized and onto your player. Even today, five years later, the iTunes-iPod integration remains the gold standard; everything else is still a distant second.”

2. The interface

Apple designed a product that was drop-dead simple to use, even if it sounds decidedly deficient when you lay it out on paper. A click wheel, five buttons, and a sparse hierarchical menu system to navigate your music library? Nonsense! Where are the volume buttons? What about the backlight? How do I create presets? And what about a power button? It’s nuts—I need buttons!

And yet, at the announcement, my most vivid memory is of that first minute with a fully loaded iPod. The elegance and simplicity of the device was stunning. It was so easy to get to a singer, a song, an album, a playlist. The way that the volume control worked was brilliant, as was the way you turned it on and off. Nothing got in the way of the music, because it was all about the music.

Apple thought about the way that most of us listen to music and squeezed it down to its essence. The company also used admirable restraint to keep from loading up the iPod with features. I might wish that my iPod let me do more things with my music—delete songs and playlists, reorder playlists, get to different menus quicker, and so forth. And, I really want features like satellite radio support so I can listen to Bob Dylan’s XM Radio show, but the iPod does the “play music” thing so well that I still can’t imagine using anything else.

3. Windows support

While it’s easy for Mac users to discount Windows, for the iPod to succeed it was crucial that Apple make the device available for PCs (even if Steve Jobs was oh-so-coy about that possibility during the launch five years ago). Not only did it have to run on a PC, that iPod/iTunes combination had to be as easy to use as it was on the Mac. The fact that Apple did it so quickly—iPods for Windows arrived less than a year after the iPod’s debut—showed that Apple was committed to the iPod as a platform. That’s what really opened the iPod up beyond its initial market of Mac users. If you look at the curve of iPod sales, the first big spike happened after Apple made the iPod Windows-compatible.

4. The iTunes Store

Making the iPod Windows-compatible set the stage for the thing that really kicked the iPod into the stratosphere: the iTunes Music Store. And, like the integration of the iPod with the computer, the integration of that ecosystem with an easy place to fill the gaping maw of 30GB of available storage was nothing short of genius. (As the 14 pages of my Music Store purchase history tells me again and again.)

I was a music fiend in the ’70s and early ’80s. I had a ton of records at one point, but after the industry switch to CDs, my buying habits changed. I didn’t spend as much on music for a number of reasons. But the cost of CDs was a big part of it, as was the reality that I would be replacing many of my old vinyl recordings with fancy (but not always better) digital sound.

Apple knew what many of us had been like: rummaging through record bins, looking for music that didn’t cost a lot and listening to the new stuff on the record store’s turntable. With the iTunes store, Apple brought that record store into my living room, and took my credit card with it. The capability to browse the store, bouncing from song to song, artist to artist, and being able to buy one song or a whole album, quickly, easily and cheaply, was an analogue to those old days—if not a vast improvement over them.

5. FairPlay

Including Apple’s Digital Rights Management technology as a reason for the iPod’s success is sure to be a controversial factor, but it can’t be discounted. If Apple was going to sell music from the major record labels, the company had to provide a mechanism to prevent buyers from sharing music purchases. There was no way a major label was going to let unprotected MP3 files out of its vault and onto the Internet without some sort of digital rights management system. FairPlay was Apple’s answer.

For DRM, FairPlay is fairly innocuous, and it’s generous as well, with its five-computer limit. And, if you’re determined to be a music pirate, burn a CD and pass your music along. You can't do that with any other system without going through some major hoops. Do you remember Sony’s little rootkit exploit? Tell me again that FairPlay is evil.

You can paint FairPlay out to be draconian, but the Store’s sales don’t lie—by and large, people are willing to put up with it. Do I like it? Not at all, but the protection really only offends my sensibilities when I run into the fact that I can’t play those damn .m4p files on my SqueezeBox. And, if you want unprotected MP3s, there’s always eMusic, to which my credit card can attest is a nice complement to the iTunes Store. And those files play on the iPod. See? In the end, it’s still all about the music.

Original iPod Introduction

Straight Dope on the IPod's Birth

http://www.wired.com/gadgets/mac/commentary/cultofmac/2006/10/71956

Thanks to Apple Computer's penchant for CIA-like secrecy, there are several myths concerning the birth of the iPod.

One of these myths is that the iPod has a father -- one man who conceived and nurtured the iconic device. Steve Jobs, of course, is one candidate; but engineer Tony Fadell has also been named the father of the iPod, as has Jon Rubinstein, the former head of Apple's hardware division. While they all played key roles in the iPod's development, the iPod was truly a team effort.

Here's the story:

In 2000, Steve Jobs' candy-colored iMac was leading the charge for Apple's comeback, but to further spur sales, the company started asking, "What can we do to make more people buy Macintoshes?"

Music lovers were trading tunes like crazy on Napster. They were attaching speakers to their computers and ripping CDs. The rush to digital was especially marked in dorm rooms -- a big source of iMac sales -- but Apple had no jukebox software for managing digital music.

To catch up with this revolution, Apple licensed the SoundJam MP music player from a small company and hired its hotshot programmer, Jeff Robbin. Under the direction of Jobs, Robbin spent several months retooling SoundJam into iTunes (mostly making it simpler). Jobs introduced it at the Macworld Expo in January 2001.

While Robbin was working on iTunes, Jobs and Co. started looking for gadget opportunities. They found that digital cameras and camcorders were pretty well designed and sold well, but music players were a different matter.

"The products stank," Greg Joswiak, Apple's vice president of iPod product marketing, told Newsweek.

Digital music players were either big and clunky or small and useless. Most were based on fairly small memory chips, either 32 or 64 MB, which stored only a few dozen songs -- not much better than a cheap portable CD player.

But a couple of the players were based on a new 2.5-inch hard drive from Fujitsu. The most popular was the Nomad Jukebox from Singapore-based Creative. About the size of a portable CD player but twice as heavy, the Nomad Jukebox showed the promise of storing thousands of songs on a (smallish) device. But it had some horrible flaws: It used Universal Serial Bus to transfer songs from the computer, which was painfully slow. The interface was an engineer special (unbelievably awful) and it often sucked batteries dry in just 45 minutes.

Here was Apple's opportunity.

"I don't know whose idea it was to do a music player, but Steve jumped on it pretty quick and he asked me to look into it," said Jon Rubinstein, the veteran Apple engineer who's been responsible for most of the company's hardware in the last 10 years.

Now retired, Rubinstein joined Apple in 1997. He'd previously worked at NeXT, where he'd been Steve Jobs' hardware guy. While at Apple, Rubinstein oversaw a string of groundbreaking machines, from the first Bondi-blue iMac to water-cooled workstations -- and, of course, the iPod. When Apple split into separate iPod and Macintosh divisions in 2004, Rubinstein was put in charge of the iPod side -- a testament to how important both he and the iPod were to Apple.

Apple's team knew it could solve most of the problems plagued by the Nomad. Its FireWire connector could quickly transfer songs from the computer to player -- an entire CD in a few seconds; a huge library of MP3s in minutes. And thanks to the rapidly growing cell phone industry, new batteries and displays were constantly coming to market.

In February 2001, during the Macworld show in Tokyo, Rubinstein made a visit to Toshiba, Apple's supplier of hard drives, where executives showed him a tiny drive the company had just developed. The drive was 1.8 inches in diameter -- considerably smaller than the 2.5-inch Fujitsu drive used in competing players -- but Toshiba didn't have any idea what it might be used for.

"They said they didn't know what to do with it. Maybe put it in a small notebook," Rubinstein recalled. "I went back to Steve and I said, 'I know how to do this. I've got all the parts.' He said, 'Go for it.'"

"Jon's very good at seeing a technology and very quickly assessing how good it is," Joswiak told Cornell Engineering Magazine. "The iPod's a great example of Jon seeing a piece of technology's potential: that very, very small form-factor hard drive."

Rubinstein didn't want to distract any of the engineers working on new Macs, so in February 2001 he hired a consultant -- engineer Fadell -- to hash out the details.

Fadell had a lot of experience making handheld devices: He'd developed popular gadgets for General Magic and Philips. A mutual acquaintance gave his number to Rubinstein.

"I called Tony," Rubinstein said. "He was on the ski slope at the time. I didn't tell him what he was going to work on. Until he walked in the door, he didn't know what he was going to be working on."

Jobs wanted a player in shops by fall, before the holiday shopping season.

Fadell was put in charge of a small team of engineers and designers, who put the device together quickly. The team took as many parts as possible off the shelf: the drive from Toshiba, a battery from Sony, some control chips from Texas Instruments.

The basic hardware blueprint was bought from Silicon Valley startup PortalPlayer, which was working on "reference designs" for several different digital players, including a full-size unit for the living room and a portable player about the size of a pack of cigarettes.

The team also drew heavily on Apple's in-house expertise.

"We didn't start from scratch," Rubinstein said. "We've got a hardware engineering group at our disposal. We need a power supply, we've got a power supply group. We need a display, we've got a display group. We used the architecture team. This was a highly leveraged product from the technologies we already had in place."

One of the biggest problems was battery life. If the drive was kept spinning while playing songs, it quickly drained the batteries. The solution was to load several songs into a bank of memory chips, which draw much less power. The drive could be put to sleep until it's called on to load more songs. While other manufacturers used a similar architecture for skip protection, the first iPod had a 32-MB memory buffer, which allowed batteries to stretch 10 hours instead of two or three.

Given the device's parts, the iPod's final shape was obvious. All the pieces sandwiched naturally together into a thin box about the size of a pack of cards.

"Sometimes things are really clear from the materials they are made from, and this was one of those times," said Rubinstein. "It was obvious how it was going to look when it was put together."

Nonetheless, Apple's design group, headed by Jonathan Ive, Apple's vice president of industrial design, made prototype after prototype.

''Steve made some very interesting observations very early on about how this was about navigating content,'' Ive told The New York Times. ''It was about being very focused and not trying to do too much with the device -- which would have been its complication and, therefore, its demise. The enabling features aren't obvious and evident, because the key was getting rid of stuff.''

Ive told the Times that the key to the iPod wasn't sudden flashes of genius, but the design process. His design group collaborated closely with manufacturers and engineers, constantly tweaking and refining the design. ''It's not serial,'' he told the Times. ''It's not one person passing something on to the next.''

Robert Brunner, a partner at design firm Pentagram and former head of Apple's design group, said Apple's designers mimic the manufacturing process as they crank out prototypes.

"Apple's designers spend 10 percent of their time doing traditional industrial design: coming up with ideas, drawing, making models, brainstorming," he said. "They spend 90 percent of their time working with manufacturing, figuring out how to implement their ideas."

To make them easy to debug, prototypes were built inside polycarbonate containers about the size of a large shoebox.

The iPod's basic software was also brought in -- from Pixo, which was working on an operating system for cell phones. On top of Pixo's low-level system, Apple built the iPod's celebrated user interface.

The idea for the scroll wheel was suggested by Apple's head of marketing, Phil Schiller, who in an early meeting said quite definitively, "The wheel is the right user interface for this product."

Schiller also suggested that menus should scroll faster the longer the wheel is turned, a stroke of genius that distinguishes the iPod from the agony of competing players. Schiller's scroll wheel didn't come from the blue, however; scroll wheels are pretty common in electronics, from scrolling mice to Palm thumb wheels. Bang & Olufsen BeoCom phones have an iPod-like dial for navigating lists of phone contacts and calls. Back in 1983, the Hewlett Packard 9836 workstation had a keyboard with a similar wheel for scrolling text.

The interface was mocked up by Tim Wasko, an interactive designer who came to Apple from NeXT, where he had worked with Jobs. Wasko had previously been responsible for the clean, simple interface in Apple's QuickTime player. Like the hardware designers, Wasko designed mockup after mockup, presenting the variations on large glossy printouts that could be spread over a conference table to be quickly sorted and discussed.

The output of a committee is a function of the quality of its members and how they're led. As the iPod came together, it garnered more and more attention from Jobs, whose insistence on excellence and high standards are stamped onto the gadget as indelibly as Apple's logo.

"Most people make the mistake of thinking design is what it looks like," Jobs told the Times. "That's not what we think design is. It's not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works."

Jobs insisted the iPod work seamlessly with iTunes, and that many functions should be automated, especially transferring songs. The model was Palm's HotSync software.

"Plug it in. Whirrrrrr. Done," Jobs told Fortune.

The iPod name was offered up by Vinnie Chieco, a freelance copywriter who lives in San Francisco. Chieco was recruited by Apple to be part of a small team tasked with helping figure out how to introduce the new player to the general public, not just computer geeks.

During the process, Jobs had settled on the player's descriptive tag line -- "1,000 songs in your pocket" -- so the name was freed up from having to be descriptive. It didn't have to reference music or songs.

While describing the player, Jobs constantly referred to Apple's digital hub strategy: The Mac is a hub, or central connection point, for a host of gadgets. This prompted Chieco to start thinking about hubs: objects that other things connect to.

The ultimate hub, Chieco figured, would be a spaceship. You could leave the spaceship in a smaller vessel, a pod, but you'd have to return to the mother ship to refuel and get food. Then Chieco was shown a prototype iPod, with its stark white plastic front.

"As soon as I saw the white iPod, I thought 2001," said Chieco. "Open the pod bay door, Hal!"

Then it was just a matter of adding the "i" prefix, as in "iMac."

Chieco declined to mention any of the alternative names that were considered. A source at Apple confirmed Chieco's story.

Athol Foden, a naming expert and president of Brighter Naming of Mountain View, California, noted that Apple had already trademarked the iPod name for an internet kiosk, a project that never saw the light of day. On July 24, 2000, Apple registered the iPod name for "a public internet kiosk enclosure containing computer equipment," according to the filing.

Chieco said the internet kiosk is probably a coincidence. He suggested that maybe another team at Apple registered the name for a different project, but because of the company's penchant for secrecy, his team wasn't aware what the other had done. And neither, apparently, was Steve Jobs. Chieco said neither Jobs -- nor anyone else -- seemed aware that the company had already registered the iPod trademark.

"The name 'iPod' makes much more sense for an internet kiosk, which is a pod for a human, than a music player," said Foden.

"They discovered in their tool chest of registered names they had 'iPod,'" he added. "If you think about the product, it doesn't really fit. But it doesn't matter. It's short and sweet."

Foden said the name is a stroke of genius: It is simple, memorable and, crucially, it doesn't describe the device, so it can still be used as the technology evolves, even if the device's function changes. He noted the "i" prefix has a double meaning: It can mean "internet," as in "iMac," or it can denote the first person: "I," as in me.

On Oct. 23, 2001, about five weeks after 9/11, Jobs introduced the finished product at a special event at Apple's HQ.

"This is a major, major breakthrough," Jobs told the assembled reporters.

iPod + Colbert - Colbert Green Screen Challenge

Five Steps to Apple Enterprise Success

http://www.macnewsworld.com/story/34477.html

Apple always has had presence in certain markets -- most notably in design, content creation and education. But mention Apple's name in the general enterprise market, and it is ignored politely, at best.

"Outside of their traditional customer base, they are not seen as an enterprise provider, and they have to prove [otherwise]," Creative Strategies senior analyst Tim Bajarin told MacNewsWorld.

However, as Apple's server software and hardware offerings proliferate, this attitude might change. Its 1U Xserve 64-bit G5 starts at US$2,999; an unlimited client license for its Unix-based Mac OS X Panther Server retails at $999; and a 1 TB Xserve RAID costs under $6,000.

Meanwhile, Xsan, Apple's storage-area network (SAN) offering, is expected to be available in the fall. This application, like OS X Panther Server, will retail at $999 and will be optimized to work with Apple's 64-bit file system.

Apple has the potential to make gains in its traditional markets and inroads into that elusive (for it) enterprise space. What steps can the company take to inspire CIOs and IT managers, many of whom already have invested in non-Apple infrastructure, to "think different" and consider its products for corporate workgroups and data centers?

Step One: Cut the Price

Tom Goguen, director of servers and storage at Apple, said in an interview with MacNewsWorld that Panther Server is central to all of Apple's enterprise offerings, adding that the company pursued an aggressive path by capping its price at under $1,000 and offering an umlimited-user license.

For his part, Bajarin said Apple is offering what he called "spectacular pricing."

"That, along with the Xserve architecture, should at the very least get serious nods from corporate America," Bajarin said.

Step Two: Exploit Open Source

Panther Server comes with several well-known open source applications powering primary services for Web, mail and user management through file services and directory services.

"Our strategy has been to adopt and contribute to open source technology rather than reinvent the wheel," Goguen explained.

According to Goguen, Apple was the first server software vendor to release Samba 3, which he said demonstrates Panther Server's capabilities in a multiplatform environment for file-and-print services.

In addition, Panther Server's LDAP implementation supports interaction with Microsoft's (Nasdaq: MSFT) Active Directory, Lotus Domino and Novell's EDir directory services, Goguen noted.

"One thing we do to differentiate ourselves is to do the testing and integration of the software we use on the server for the customer," Goguen said.

"For example, an administrator can set up e-mail services in a few checkboxes instead of having to build software from source and test prior to setup."

Step Three: Grow Its Market

IDC server analyst Mark Melenovsky said that, although most Unix-based low-end server deployments involve Linux, Apple has the potential to gain market share in this area with its Xserve.

Melenovsky sees Apple's aggressive pricing and similarity to Linux as a way to counter the popular open source operating system and its relatively low price to deploy.

"The PowerPC chip could be an inhibitor as there is a general perception that the x86 platform is more broad," Melenovsky said. However, he said that Apple could counter this if IBM (NYSE: IBM) sees success with its PowerPC server hardware -- which would serve to build recognition of the G5's architecture.

Step Four: Leverage High-Performance Computing

Melenovsky observed that so-called "high-performance computing" is another area in which Apple can gain traction. Traditionally, such environments were found primarily in academia, science and government.

"Now we are seeing financial services companies needing to analyze portfolios and retail operations automating supply-chain management," Melenovsky said, adding that people working in these areas are examining high-performance clusters as a workable option.

Goguen said Xsan has the goods to accommodate these advanced clustering and storage needs. According to him, the Xsan platform will handle files and volumes up to 16 terabytes in size and support concurrent access of up to 64 users directly connected to the storage area network over fiber channel.

Step Five: Play Nice with Others

"We are targeting our traditional markets that have demand for large files and streaming audio and video," Goguen continued. "However, Xsan is a solution across the enterprise -- whether it is for [network attached storage] replacement or in a multi-operating-system environment with cluster and high-availability storage needs."

Goguen said Xsan is 100 percent compatible with the StorNext File System from Advanced Digital Information Corporation (ADIC), which enables Xsan to deploy alongside Unix and Windows servers.

Bajarin believes this is critical to Apple's success, at the enterprise level.

"When you have mixed environments with Linux and Unix back ends, the [Apple's] compatibility opens some doors," he said.

Staying true to their reputation for usability, Goguen pointed out Xsan includes management tools for administering implementations at no additional cost.

"We have been working on it for quite some time," Goguen said. "We are offering a multiterabyte, multi-SAN solution for under $50,000 and the tools to manage it.

The Key to Apple's Success: If You Make It Easy, They Will Come

http://lowendmac.com/archive/05/0211.html

In the mid-90s Apple's products were less than up to par. The Performa line had constant problems (such as the 5200, which had a recall on the display cable), and PowerBooks were rather slow and also problematic (like the 5300, which had recalls on the battery, logic board, and various plastic case parts).

Of course, once these problems were fixed, the computers generally worked well. That is, assuming that you don't consider how buggy System 7.5.1 was on PowerPC-based Macs and how the Mac software of the time (a certain Microsoft product comes to mind) wasn't very good compared to the Windows version.

Simple Is as Simple Does

Then came the iMac, the computer that was the top-selling model of the late 90s. It was pretty much un-upgradeable - except for the RAM and hard drive - and was completely incompatible with almost every device that existed in the computing world.

And it had no floppy drive.

Most people were amazed that it sold so well. It was so basic, yet there were waiting lists for them!

That's because until then just about every computer company completely ignored consumers who wanted something simple, something that would get them online so they could do email.

Sure, in 1994 Compaq had their all-in-one Presario 500 series, and Apple had its Performa 500 and 5x00 series, but these were marketed as "multimedia computers" - basically computers that could do anything and everything you and your family wanted. Both Compaq and Apple put a whole bunch of expansion ports and add-on slots in these machines, and, like all the other computers out in 1995, they were ugly.

The iMac was a newer variation of the multimedia computer, but it was marketed differently. It was marketed as "Step one: Plug it in. Step two: Turn it on. Step three: There is no step three!"

This was exactly the machine that the computer-intimidated needed in 1998.

It's moved up from there. Those who knew very little about computing in 1998 all of a sudden had new needs, as their original iMac has got them involved and interested in using the computer. They want to be able to connect their digital camera effortlessly. They want to be able to use an MP3 player. They wanted the additional capabilities so their system could expand with their needs (the original iMac lacked a lot of that).

Apple realized this. Newer iMacs added options for wireless networking, Bluetooth, and now comes standard with FireWire ports and a video-out port to support a second display.

It's no longer just a "There is no step three" computer. It's a simple-to-use computer that can grow with a users' knowledge of computing. And that's not even mentioning the additional improvements in Mac OS X 10.3 compared to Mac OS 8.1 and 8.5 that shipped with older iMacs.

Apple's had their little issues, though. The G4 Cube was a marketing disaster. It was too expensive ($1,799 to $2,299), not upgradeable enough, didn't have enough features to compensate for the price, and the models that did get sold had too many problems with the touch-sensitive power switch (which should have probably been called "brush-sensitive").

Further, there was no clearly defined market for the Cube. Professionals didn't want it, because they couldn't install additional hard drives or PCI cards. Home users didn't want it, because they figured out that buying the 400 MHz G4 tower for $1,599 was not only cheaper, but they'd have the additional expandability if they ever wanted to add anything to their system.

Apple has obviously learned from their mistake. The "new Cube" (the Mac mini) has a clearly defined market - those switching from Windows.

Changing Times

Apple's a lot more fashionable today than it was five years ago. "Oh, you have a Macintosh?" has gone from implying disdain to implying a certain curiosity - "Hmm, I've never thought about buying one, maybe I should."

I think a lot of that popularity isn't due to anything Apple's done but to the increasing problems with Windows. Windows XP is a four-year-old operating system and has more viruses, worms, spyware, and adware then anyone should have to deal with. (I'm not blaming Microsoft here; if XP had 10% of the market, there'd be a lot fewer problems.)

Internet Explorer 6 has far too many issues, too, and this is Microsoft's fault. They haven't done enough to keep their browser up to date, and people are starting to dislike it more and more.

Apple's Mac OS X is finally working like it should - no more 7.5.x "Type 2 Error" and OS 8.0 "There is a problem with the control panel Apple Menu Options" issues. And Mac software is actually decent for once in quite some time.

It's excellent luck for Apple. All they need to do is put out products people want to buy - and so far they're doing just that.

Top 5 Apple Flops

Big, Bad Apple

European regulators want to shuffle iTunes—but do consumers on the continent want to play along?

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/17312084/site/newsweek/

March 5, 2007 issue - Apple, Inc., maker of the Macintosh computer and the iPod, never lets anyone forget what it isn't—Microsoft. The company's ads show a hipster named Mac humiliating a pale, pudgy loser named PC; its slogan urges consumers to "Think different." But as Apple has evolved from struggling computer maker to digital media giant, it now finds itself cast in a role that had been Microsoft's alone—European corporate villain.

When Apple's iTunes online music store arrived in Europe in mid-2004, it became an overnight sensation. Customers downloaded 800,000 songs in the first week. Soon iTunes owned as much as 70 percent of the entertainment download market. By giving customers an easy, affordable and legal way to download MP3 files from the Web to their iPods, Apple had turned an illicit act into a viable business, one it means to keep for itself. CEO Steve Jobs allowed the Mac to become an also-ran rather than open its operating system. Now, he's being pushed to loosen the reins on iTunes—and he's pushing back.

Last summer the first signs that Europe might be losing its taste for Apple appeared when Norway's consumer-protection agency filed a complaint claiming that iTunes violates Norwegian law. At the heart of the complaint was Apple's inclusion of digital-rights-management (DRM) software in iTunes, which prevents files downloaded there from being played on non-Apple gadgets like mobile phones. DRM also prevents songs downloaded from other sites, like Yahoo or Napster, from playing on an iPod. Put simply, "customer friendly" Apple was tying its customers' hands.

Norwegian consumer watchdogs weren't the only ones to complain. By the year-end, regulators in Finland, France, Sweden, Denmark and Germany had opened investigations into whether DRM software was fair. On Jan. 27, the Dutch upped the ante, setting a September deadline for Apple to dump its "illegal" DRM, a month earlier than a similar deadline set down by Norway.

Sound familiar? It should. Courts in Europe and the United States held that Microsoft has locked out competitors' products in violation of antitrust laws by bundling its media player and Web browser in Windows. But only in Europe, where trustbusters have become more aggressive than in the United States, did they force the company to unbundle its products. Now they want to force Apple to make its products work with those made by other companies.

So what's driving this sudden burst of rancor? The answer may be partly a question of size. With $9.6 billion in revenue from digital entertainment, Apple has become a colossus; it owns 70 percent of the European market for digital entertainment. As Keith Woolcock, a technology analyst with Westhall Capital in London, observes, "It's the curse of success. They're walking into the middle of every issue from labor standards to consumer rights, just by being big."

Apple is also disruptive. Already, the company has turned music giants on their heads. As the boundaries between the Web, television, music, movies and phones collapse onto each other, Apple has so far been the most successful rider on a wave that could swamp companies as dissimilar as France's Vivendi, Finland's Nokia and Germany's Bertelsmann. It's no wonder that in each of these countries, regulators have added their voices to the outcry against iTunes. "Any time politicians get involved, you have to assume something political," Mike McGuire, a Silicon Valley-based analyst with Gartner Research, observes dryly. "I actually think this is more about European politics than anything else," adds Mark Mulligan of Jupiter/Kagan Research in London. Should the various cases end up in court, Apple could mount a strong defense. After all, DRM was forced upon the company by the major music labels, three of which are European, in exchange for the rights to sell their music on the Web. It's an irony that's not lost on Apple CEO Steve Jobs, who earlier this month made this point in an open memo to consumers, posted on the company's site. It was a clever move to align the company with the sort of anti-DRM consumer sentiment overwhelmingly expressed on Apple users' chat sites and blogs. Denouncing DRM and shifting the blame for Apple's use of it isn't the same as getting rid of it, but it does suggest that Jobs wants to avoid looking like the bad guy, even if his company still benefits from bad behavior.

Benefiting they are. Apple's European sales were up 33 percent last year. But there are signs that the company's core fan base of techies is cooling. One Internet poll shows that 98 percent of respondents favor dumping DRM. Digital-rights pressure groups like Defective by Design have picketed Apple stores in London, and called upon everyone from Parliament to Bono to take up the cause of interoperable software standards. Keeping ahead of this sort of public opinion is a smart idea, and one that may ultimately separate Apple from its cartoon rival. Serial litigator Microsoft became so reviled that the creators of the raunchy "South Park" cartoon series could bring movie audiences to their feet, cheering a scene in which an animated Bill Gates gets shot in the head.

Right now a similar fate for the media-savvy Jobs seems a way off. His careful courting of the company's hugely loyal consumer base coincides with Apple's much-anticipated foray into the mobile-phone business. That's an industry European firms like Nokia, Philips and Ericsson dominate, and one that the EU keeps a close eye on. As Apple unveils its latest disruptive technology, the iPhone, this summer, Jobs is no doubt hoping that Europe's regulators and consumers alike will "think different."

Steve Jobs - Next Computers

Apple's success not always so sweet

Hype over the iPhone brings to mind some products that fell short

http://www.chicagotribune.com/business/chi-fri_apple_0629jun29,0,2050083.story?coll=chi-business-hed

NEW YORK -- When a Roman general returned from a successful campaign and was rewarded with a triumphal parade through the city, a slave stood behind him on his chariot to whisper the words "Memento mori" in his ear.

The Latin phrase means "Remember that you are mortal," and was intended to keep the general's pride manageable. With the launch of the tremendously hyped iPhone upon us, it might be worth reminding Apple Inc. and the buying public that not every product the company has put out has been as successful as, say, Julius Caesar's conquest of France.

So here's a memento mori for Apple, listing some of its greatest misses:

- The Rokr, 2005. It's easy to forget that the iPhone isn't Apple's first venture into the cell phone business. Schaumburg-based Motorola Inc. launched the Rokr in late 2005 in partnership with Apple. As a phone, it was decent if unexciting, but as a music player, it fell far short of the iPod. It could hold only 100 songs, and transferring them from a computer was a slow process.

- The Newton, 1993. The iPhone is a slab with a few buttons, mainly controlled through a touch screen. That pretty much also describes the Newton, a personal organizer that was hailed as revolutionary when it came out. Text was entered by writing on the screen with a stylus, but the Newton was poor at interpreting it.

Palm Inc. later got the concept of a stylus-based hand-held organizer to work by creating a special alphabet and making the device more pocketable.

The iPhone will rely on an on-screen keyboard for text entry, rather than a stylus and handwriting recognition.

- The Cube, 2000. This small desktop computer was beautifully encased in a cube of clear plastic. It won design awards but was a flop in stores because of its high price. The Cube didn't work differently from other Macintosh computers; it just looked different. People weren't willing to pay a premium for the design alone. The iPhone will both look and work differently from other phones, so the higher price of as much as $599 might well be justified.

- EWorld, 1994. This was Apple's attempt to create an alternative to America Online, then a pre-World Wide Web Internet service with bulletin boards and e-mail. EWorld was easy to use and had an appealing interface, but closed after just two years, killed by its exclusivity -- it was open only to Mac users. Today's Apple certainly doesn't stint on marketing, and though it clearly favors the Macintosh, its iPod and iPhone work on Windows PC.

- The one-button mouse, 1983. There's not much to criticize about this design decision at the time it was made. Mice were new, and Apple made an informed choice to use only one button for maximum ease of use.

But Microsoft Corp.'s Windows operating system showed that two buttons were useful and manageable, and Apple's one-button regime started to become a liability in the '90s, at least when it came to winning over Windows users. Despite this, Apple held out until 2005 before introducing a mouse that could sense right and left clicks.

In 10 years, will the iPod be remembered as the ancestor of the iPhone? Or will it be the iPhone that's remembered as a brilliant but short-lived inspiration, like the Newton? Nobody can say. In consumer electronics, a decade is a lifetime, and everyone is mortal.

all about Steve - All-time favorites

all about Steve - Friendly competition

all about Steve - Boom!

Bill Gates Praising Apple Computers

Weekend Update iPhone Special

The New iRack from Apple

Apple Mac Guy -VS- PC Guy

![Brotherhood" (2006) [TV-Series]](http://photos1.blogger.com/x/blogger2/1421/379621144723082/211/z/425926/gse_multipart33129.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment