Blackwater USA is a private military company and security firm founded in 1997 by Erik Prince and Al Clark. It is based in the U.S. state of North Carolina where it operates a tactical training facility which it claims is the world's largest. The company trains more than 40,000 people a year, from all the military services and a variety of other agencies. The company markets itself as being "The most comprehensive professional military, law enforcement, security, peacekeeping, and stability operations company in the world". At least 90% of its revenue comes from government contracts, two-thirds of which are no-bid contracts.

Corporate structure

Blackwater USA consists of nine companies

Blackwater Training Center

Blackwater Training Center offers tactics and weapons training to military, government, and law enforcement agencies. See facilities below. Blackwater Training Center also offers several open-enrollment courses periodically throughout the year, from hand to hand combat (executive course) to precision rifle marksmanship.

Blackwater Target Systems

This division provides and maintains target range steel targets and a "shoothouse" system

Blackwater Security Consulting (Moyock, North Carolina)

Blackwater MD 530F in IraqBlackwater Security Consulting (BSC) was formed in 2002. BSC is one of 180 private security firms employed during the Iraq War to guard officials and installations, train Iraq's new Army and Police, and provide other support for Coalition Forces.

Blackwater Security Consulting is very well equipped and known to use:

MD-530F "Little Bird" helicopters, organized into Quick Response Force (QRF) teams.

Sikorsky S-92 helicopters are known to be used based on Blackwater USA's careers page.

AB 412 utility helicopters in use in Iraq.

BAE RG-31 Mamba armored vehicles, purchased from the British Army are known to be used to transport personnel along Route Irish[4]

Force Protection Industries Cougar H[5]

Embraer EMB 314 Super Tucano - Blackwater has purchased one of these aircraft for pilot training in the US, with possible plans for more in the Counter Insurgency (COIN) role later.[6][7]

Blackwater has won a S-70A modification/upgrade program for the UAE Special Operations Command which include Mounts for Machine Guns, Heads Up Display, Secure Communications and FLIR systems EO-IR sensor with Vectr mission system.

Blackwater K-9

Training canines to work in patrol capacities as war dogs, explosives and drug detection, and various other roles for military and law enforcement duties.

Blackwater Airships, LLC

Blackwater Airships LLC was established in January 2006 to build a remotely piloted airship vehicle (RPAV).

Blackwater Armored Vehicle

Blackwater recently introduced its own armored personnel carrier, the Grizzly APC.[8]

Blackwater Maritime

Blackwater Maritime Security Services offers tactical training for maritime force protection units. In the past it has trained Greek security forces for the 2004 Olympics, Azerbaijan Naval Sea Commandos, and Afghanistan’s Ministry of Interior.[9]

Raven Development Group

In 1997, the Raven Development Group was established to design and build Blackwater USA's training facility in North Carolina.

Aviation Worldwide Services (Presidential Airways and STI Aviation)

Aircraft maintenance and tactical transportation. Presidential Airways claims to hold a Secret Facility Clearance from the U.S. Department of Defense.[10]

Greystone Limited

A private security service, Greystone is registered in Barbados, and employs third country nationals for offshore security work.

Personnel

Blackwater's president, Gary Jackson, and other business unit leaders are former Navy SEALs. Blackwater was founded and is owned by Erik Prince, who is also a former Navy SEAL.[11]

Prince and Jackson are also major contributors to the Republican party. In addition, Prince was an intern in George H.W. Bush's White House and campaigned for Pat Buchanan in 1992.[12]

Cofer Black, the company's current vice chairman, was the Bush adminstration's top counterterrorism official when 9/11 occurred. In 2002, he famously stated: "There was before 9/11 and after 9/11. After 9/11, the gloves come off." But Black is not alone, Blackwater has become home to a significant number of former senior CIA and Pentagon officials. Robert Richer became the firm's Vice President of Intelligence immediately after he resigned his position as Associate Deputy Director of Operations in fall 2005. He is formerly the head of the CIA's Near East Division.[13]

In October 2006, Kenneth Starr, independent counsel in the impeachment case of Bill Clinton in 1999, represented Blackwater in front of the US Supreme Court in a case related to the March 2004 killing of four Blackwater employees in Fallujah, Iraq.[14] In response to that event, Blackwater also hired the Republican lobbying and PR firm, the Alexander Strategy Group.[15]

Facilities

The facility, located in North Carolina, is composed of several ranges, indoor, outdoor, urban reproductions and has over 7,000 acres (28 km²) of land spanning Camden and Currituck counties.

It is one of the largest firearms training facilities in the world. Company literature claims that the company runs "the largest privately owned firearms training facility in the world."

In November 2006 Blackwater USA announced it recently acquired an 80-acre (30 ha) facility 150 miles (240 km) west of Chicago, in Mount Carroll, Illinois to be called Blackwater North. That facility is now operational.

Blackwater is also trying[16] to open a facility in California for military training,[17] in Potrero, San Diego County.[18][19]

History

Blackwater USA was formed in 1997 to provide training support to military and law enforcement organizations. In 2002 Blackwater Security Consulting (BSC) was formed. It was one of several private security firms employed following the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan. BSC is one of over 60 private security firms employed during the Iraq War to guard officials and installations, train Iraq's new army and police, and provide other support for occupation forces.[20] Blackwater was also hired during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina by the Department of Homeland Security, as well as by private clients, including communications, petrochemical and insurance companies.[21] In each case, Blackwater received a non-bid contract. Overall, the company has received over 500 million dollars in government contracts.[22]

Iraq involvement

In 2003, Blackwater landed its first truly high-profile contract: guarding Ambassador L. Paul Bremer in Iraq, at the cost of $21 million in 11 months. Since June 2004, Blackwater has been paid more than $320 million out of a $1 billion, five-year State Department budget for the Worldwide Personal Protective Service, which protects U.S. officials and some foreign officials in conflict zones.[23] In 2006, Blackwater won the remunerative contract to protect the U.S. embassy in Iraq, which is the largest American embassy in the world. It is estimated by the Pentagon and company representatives that there are 20,000 to 30,000 armed security contractors working in Iraq, and some estimates are as much as 100,000, though no official figures exist.[24][25] Of the State Department's dependence on private contractors like Blackwater for security purposes, U.S. ambassador to Iraq, Ryan Crocker, told the U.S. Senate: "There is simply no way at all that the State Department's Bureau of Diplomatic Security could ever have enough full-time personnel to staff the security function in Iraq. There is no alternative except through contracts."[26]

For work in Iraq, Blackwater has drawn contractors from their international pool of professionals, a database containing "21,000 former Special Forces troops, soldiers, and retired law enforcement agents," overall.[27] For instance, Gary Jackson, the firm's president, has confirmed that Bosnians, Filipinos, and Chileans (many trained under Augusto Pinochet), "have been hired for tasks ranging from airport security to protecting Paul Bremer, the head of the Coalition Provisional Authority."[28]

[edit] Fallujah mission

Main article: 31 March 2004 Fallujah ambush

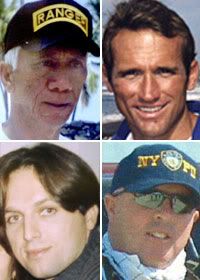

On March 31, 2004, Iraqi insurgents in Fallujah attacked a convoy containing four American private military contractors from Blackwater USA who were conducting delivery for food caterers ESS.[29] The four armed contractors Scott Helvenston, Jerko Zovko, Wesley Batalona and Michael Teague, were attacked and killed with grenades and small arms fire. Their bodies were hung over a bridge crossing the Euphrates.[30]

Photos of the event were released to news agencies worldwide, causing a great deal of indignation and moral outrage in the United States. The event led to a failed U.S. operation to occupy the city in the First Battle of Fallujah, and the later successful attempt seven months later in the Second Battle of Fallujah.

[edit] Later incidents

In April 2004, a few days after the Fallujah bridge hanging, a small team of Blackwater employees, along with soldiers of the Spanish Army, held off over four hundred insurgents outside the Coalition Provisional Authority Headquarters in Al Najaf, Iraq, waiting over three hours for U.S. troops to arrive. The Headquarters was surrounded and it was the last friendly area in the city. Supplies were running low. During this fight, a small but highly trained volunteer group of Blackwater contractors flew on a rescue mission to the Coalition Provisional Authority Headquarters to maintain its control, and bring an injured U.S. Marine back to safety outside of the city.[31] [32][33]

In April 2005 six Blackwater independent contractors were killed in Iraq when their Mi-8 helicopter was shot down. Also killed were three Bulgarian crewmembers and two Fijian gunners. Initial reports indicate the helicopter was shot down by rocket propelled grenades. The six Americans killed have been identified as:[34]

Robert Jason Gore, of Nevada, Iowa

Luke Adam Petrik of Conneaut, Ohio

Jason Obert of Fountain, Colorado

Steve McGovern of Lexington, Kentucky

Erick Smith of Waukesha, Wisconsin

David Patterson of Havelock, North Carolina

The three Bulgarians have been identified as:

Lyubomir Kostov [35]

Georgi Naidenov [36]

Stoyan Anchev [36]

On January 23, 2007, five Blackwater contractors were killed in Iraq when their Hughes H-6 helicopter was shot down. The incident happened in Baghdad, Haifa Street. The crash site was secured by a Personal Security Detail Platoon, callsign "Jester" from 1/26 Infantry, 1st Infantry Division. Three Iraqi insurgent groups claimed responsibility for shooting down the helicopter, however, this has not been confirmed by the US.[37] A US defense official has confirmed that four of the five killed were shot execution style in the back of the head, but did not know whether the four were still alive when they were shot.[38] Robert Young Pelton broke the full details of the crash on his site. Pelton also met and flew with the Little Bird pilots.[39]

On August 12, 2007, an MSNBC report noted the largely unaccountable and unsupervised nature of security contractor activities, and the high number of casual or indiscriminate civilian killings attributed to them. According to the State Department, on December 24, 2006, a civilian U.S. contractor, allegedly a Blackwater employee, shot and killed an Iraqi security officer.[40] In late May 2007, Blackwater contractors, "opened fire on the streets of Baghdad twice in two days... and one of the incidents provoked a standoff between the security contractors and Iraqi forces, U.S. and Iraqi officials said."[41] And on May 30, 2007, Blackwater employees shot an Iraqi civilian deemed to have been "driving too close" to a convoy of Blackwater armored vehicles.[42][43] Other private security contractors, such as Aegis Defence Services have also been accused of similar actions.[44] However, "Doug Brooks, the president of the International Peace Operations Association, a trade group representing Blackwater and other military contractors, said that in his view, military law would not apply to Blackwater contractors working for the State Department."[45]

[edit] Revocation of Iraq license

On September 17, 2007, Blackwater's license to operate in Iraq was revoked following an incident that occurred the previous day. A convoy of US State Department vehicles guarded by Blackwater was attacked in the al-Yarmukh neighborhood of western Baghdad. According to the incident report, the attack occured at 12:08pm, when "the motorcade was engaged with small arms fire from several locations". One vehicle was disabled in the attack, and had to be towed away. The report goes on to state that "The team returned fire to several identified targets" before leaving the area, and that a second convoy en-route to help was "blocked/surrounded by several Iraqi police and Iraqi national guard vehicles and armed personnel".[46] A Blackwater helicopter was also present, and according to a Washington Post employee, it fired several times from the air, although Blackwater has denied this.[47] Sources have also stated that the fighting began after an explosion, possibly a mortar round, went off close to the convoy, although this is not reflected in the incident report, which can be found here.[48] Iraqi Brigadier-General Abdul-Karim Khalaf confirmed that a mortar had landed close to the convoy and said the US firm had 'opened fire randomly at citizens'. Nine civilians were killed including one Iraqi policeman. No State Department officials were wounded or killed. [49] The State Department had not been notified of the Iraqi government's decision, and declined to speculate how it might affect State Department activities. Many doubt that the Iraqi government will have the resolve to revoke Blackwater's license over the long term due to Blackwater's political influence and other factors. Retired Marine Lt. Col. Bill Cowan, an independent military analyst and co-chairman of security consulting firm WVC3 Group, was quoted on September 17, 2007, by the Associated Press as saying: "You can bet the U.S. embassy is doing backflips right now pressuring the Iraqis not to revoke their license." [50]

Interior Ministry spokesman Brig. Gen. Abdul Kareem Khalaf said "the investigation is ongoing, and all those responsible for Sunday's killing will be referred to Iraqi justice." Iraqi authorities have issued previous complaints about shootings by private military contractors, but Iraqi courts do not have the authority to bring contractors to trial without the consent of their home country, according to a report from the Congressional Research Service.[51].

The Private Security Company Association of Iraq, in a document last updated on July 3, 2007, lists Blackwater as having applied for, though not yet as having received, the license in question.[52] Blackwater's operations on behalf of the US Department of State and the CIA might be unaffected by this claimed license revocation.[53] Also, it is not clear whether the license revocation is permanent.[54] Nonetheless, the banning was described by P.W. Singer, an expert on the private military industry, as "inevitable," given the US governments' reliance on and lack of oversight of the private military industry in Iraq.[55]

Blackwater has denied any wrongdoing in the incident.[56] The U.S. State Department said it plans to investigate what it calls a "terrible incident."[51] Henry Waxman, the chair of the US House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, also said his committee would hold hearings "to understand what has happened and the extent of the damage to U.S. security interests."[56]

[edit] Litigation

Blackwater is currently being sued by the families of the four contractors killed in Fallujah in March, 2004. The families allege that they are not suing for financial damages, but rather for the details of their sons' and husbands' deaths. They claim that Blackwater has refused to supply these details, and that in its "zeal to exploit this unexpected market for private security men, showed a callous disregard for the safety of its employees."[57] Four family members testified in front of the House Government Reform Committee on February 7, 2007. They asked that Blackwater be held accountable for future negligence of employees' lives, and that Federal legislation be drawn up to govern contracts between the Department of Defense and the defense contractor.[58] Blackwater has counter-sued the lawyer representing the empty estates of the deceased for $10 million on the grounds that the lawsuit was contractually prohibited from ever being filed.[59]

On April 19, 2006, The Nation magazine published an article titled, "Blood Is Thicker Than Blackwater," concerning the lawsuit against Blackwater brought by some of the families of the four deceased employees.[60] The article discussed the removal of the word "armoured" from already-signed contracts, and other allegations of wrongdoing.

According to an Army report, in November 2004, a Blackwater plane, "in violation of numerous government regulations and contract requirements," crashed into a mountainside, killing all six aboard.[61] The families of the three soldiers killed -- Lt. Col. Michael McMahon, Chief Warrant Officer Travis Grogan and Spec. Harley Miller -- filed a wrongful death suit against Blackwater, alleging negligence. However, Presidential Airways, a division of Blackwater, questioned the hastiness of the Army's report, stating that it "contains numerous errors, misstatements, and unfounded assumptions."[62]

[edit] Post-Katrina Involvement

Blackwater USA was employed to assist the Hurricane Katrina relief efforts on the Gulf Coast. According to a company press release, it provided airlift, security, and logistics and transportation services, as well as humanitarian support. Unofficial reports claim that the company also acted as law enforcement in the disaster stricken areas, such as securing neighborhoods and "confronting criminals".[63]

Blackwater moved about 200 personnel into the area hit by Hurricane Katrina, most of whom (164 employees) were working under a contract with the Department of Homeland Security to protect government facilities[64], but the company held contracts with private clients as well.

Overall, Blackwater had a "visible, and financially lucrative, presence in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina as the use of the company contractors cost U.S. taxpayers $240,000 a day."[65] There has been much dispute surrounding governmental contracts in post-Katrina New Orleans, especially no-bid contracts such as the one Blackwater was awarded. Blackwater's heavily-armored presence in the city was also the subject of much confusion and criticism.

[edit] Other employments

Blackwater USA is one of five companies picked by the Department of Defense Counter-Narcoterrorism Technology Program Office in a a five-year contract for equipment, material and services in support of counter-narcoterrorism activities. The contract is worth up to $15 billion. The other companies picked are Raytheon, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Arinc Inc.

Blackwater USA has also been contracted by various foreign governments. In 2005, it worked to train the Naval Sea Commando regiment of Azerbaijan, enhancing their interdiction capabilities on the Caspian Sea.

[edit] Controversy and criticism

In March 2006, Cofer Black, vice chairman of Blackwater USA, allegedly suggested at an international conference in Amman, Jordan, that the company is ready to move towards providing security professionals up to brigade size for humanitarian efforts and low intensity conflicts. Mr. Black denies the allegation. Critics have suggested this may be going too far in putting political decisions in the hands of privately owned corporations.[70] The company denies this was ever said.

Critics claim that Blackwater's private military company self-description is a euphemism for mercenary activities.

Perhaps the most thorough book about Blackwater was published in 2006 by investigative journalist Jeremy Scahill, titled Blackwater: The Rise of the World's Most Powerful Mercenary Army.

Author Chris Hedges wrote about the establishment of mercenary armies as a threat to democracy in his June 3, 2007 article for the Philadelphia Inquirer, "What if our mercenaries turn on us?" [72] Reprinted in the New York Times, Particularly of note in the article is the question being raised of the wisdom of allowing private enterprises to become involved in combat operations, and its potential advantages and disadvantages.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blackwater_USA

Blackwater USA

Type: Wholly-Owned Subsidiary of The Prince Group

Address: P.O. Box 1029, Moyock, North Carolina 27958, U.S.A.

Telephone: (252) 435-2488

Fax: (252) 435-6388

NAIC: 561612 Security Guards and Patrol Services

http://www.answers.com/Blackwater+USA?cat=travel

Based in Moyock, North Carolina, close to Fort Bragg, the notoriously private company Blackwater USA bills itself as "the most comprehensive professional military, law enforcement, security, peacekeeping, and stability operations company in the world." Founded by former Navy SEALs, Blackwater is comprised of five business units. The Blackwater Training Center, the company's original focus, is one of the best facilities of its kind in the world, located on some 6,000 acres of private land. More than 50,000 law enforcement, military, and civilian personnel have trained here since opening in 1998. The center includes a number of live fire shooting ranges and tactical training facilities, like mock-ups of urban settings, a high school, and naval ship. Blackwater Security Consulting provides vulnerability assessments and risk analysis and training services, and supplies clients with mobile security teams comprised of former members of U.S. military special operations units and foreign intelligence services. Blackwater Target Systems offers indoor and outdoor shooting range target systems. Blackwater K9 maintains two facilities used to train dogs for law enforcement, the military, and commercial organizations in such areas as patrolling and the detection of explosives. The final business unit is Raven Development Group, which was launched in 1997 to design and construct the Blackwater training facility and now offers its services to government and commercial clients, capable of building an office complex in the United States as well as secure facilities in Iraq. It was in Iraq that Blackwater came to the attention of the general public after a number of its operators were killed in a pair of well publicized incidents, which brought notice to the increasing reliance of the U.S. military on professional security firms in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere in the world.

Soldiers for hire have essentially been around since man first began forming armies. While the Geneva Convention held after World War II expressly banned the use of mercenaries, "soldiers of fortune" continued to show up at hot spots around the world. With the demise of the Soviet Union an opportunity was created for a new breed of professional security companies. "At that time," according to a 2004 New York Times' article, "many nations were sharply reducing their military forces, leaving millions of soldiers without employment." Many of them went into business doing what they knew best: providing security or training others to do the same. The proliferation of ethnic conflicts and civil wars in places like the Balkans, Haiti and Liberia provided employment for the personnel of many new companies. The United States employed a small number of these private contractors with the 1991 Gulf War. When it was over Defense Secretary Richard Cheney hired Halliburton subsidiary Brown & Root to study how private military companies might support the military in combat zones.

Blackwater was one of dozens of a new breed of private military companies that sprung up in the 1990s in the United States and the United Kingdom. It was founded in 1997 by former Navy SEALs Gary Jackson and Erik Prince. It was Prince, one of the richest men to have ever served in the U.S. military, who furnished the financial backing and business acumen needed to launch Blackwater.

Prince was the son of Edgar D. Prince, a highly religious man who at the age of 33 in 1965 quit his job as chief engineer of a machine tools company to start his own die cast business. In 1972 Prince Corp. branched into the auto parts industry by inventing the lighted vanity visor for front-seat passengers, first offered on the 1973 Cadillac. This led to the introduction of a multitude of other car interior components and Prince Corp. enjoyed exceptional growth over the next 20 years. As he grew wealthy Edgar Prince became prominent in right wing politics, supporting like-minded candidates around the country. In 1988 he helped Gary Bauer in the establishment of the "pro-family" lobbying group, the Family Research Council.

Erik Prince followed in his father's footsteps to a large degree: devout in his religion, smart in business, and firm in his patriotism. In the late 1980s he attended a small liberal arts school, Hillsdale College, where he studied economics. He also got an education in politics, becoming one of the first interns at the Family Research Council in Washington, D.C. He then worked as a defense analyst for conservative republican Congressman Dana Rohrbacher, before becoming a White House intern for President George H.W. Bush. In a rare interview (his father scrupulously avoided the press), Prince told the Grand Rapids Press in 1992, "I saw a lot of things I didn't agree with--homosexual groups being invited in, the budget agreement, the Clean Air Act, those kinds of bills. I think the administration has been indifferent to a lot of conservative concerns."

Prince returned to Hillsdale and became a member of the local volunteer fire department, attending classes with his emergency radio, and sometimes startling classmates as he rushed off to fight a fire. Prince transferred to the U.S. Naval Academy but resigned, preferring instead to join the Navy and earn a commission as a lieutenant. He then became a Navy SEAL (the acronym drawn from the attack routes of sea, air, and land). According to a Special Forces officer quoted by Raleigh, North Carolina's News & Observer, "Prince was a first-class SEAL, he was the real deal." He would serve four years with Seal Team 8 in Norfolk, Virginia.

In March 1995 Edgar Prince died of a massive heart attack, found on the floor of an elevator shortly after leaving the executive dining room at Prince Corporation headquarters. By now the automotive industry was going global and the private company faced a crossroads. The Prince family decided to sell off the automotive unit, receiving $1.35 billion from Johnson Controls Inc. A year later in 1996 Eric Prince quit the NAVY and returned home to Michigan to run the remaining family companies, which included the original die cast machine business, an airplane leasing operation, and a real estate development company. However, the 27-year-old soon found a venture that was more to his liking.

In 1997 Prince and Jackson went into business together to build a first class private military training center, believing there was an opening for such a facility as the military closed the doors on a number of its training centers. They bought a large section of farmland in Camden and Currituck counties in North Carolina, some 25 miles from Fort Bragg. Because the large amount of peat in the area turned the water black in the drainage canals they called the company Blackwater USA. For a logo they chose a bear claw, an allusion to the large brown and black bear population in the area.

Blackwater experienced some difficulty in gaining permission from Currituck County to build its training center because officials worried that the firing ranges might disturb residents in nearby Moyock, a growing community. Instead, Blackwater turned to Camden Country where it found a more receptive hearing. What resulted would be a world class training complex. Writing for Handguns in 2000, Katherine Rauch took a three-day handgun course at Blackwater and offered a glimpse at the facilities: "There are steel movers and steel plates, steep Pepper Poppers and stationary steel, along with computerized pneumatic steel targets and automated paper targets. There's Simunitions complex of four buildings, with a live-fire 'Hogan's Alley' right across the 'street,' along with two all-steel shoot houses, a 1,200-yard range and a 7,000-square-foot schoolhouse dubbed 'R.U. Ready High.'... All This, plus breakfast and lunch, along with a private room (by request) in the bunkhouse complex with its own little deck overlooking one of the many ponds on the property."

The Blackwater training center was open for business in 1998, but in the early months had difficulty in drumming up much business. The company became adept, however, at keeping tabs on national and international news, then adding facilities and training programs to meet perceived needs. For example, R.U. Ready High School was built after the 1999 shootings at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado. It was essentially a two-story, 24-room, six-stairwell, all-steel building that allowed for the use of live gunfire inside and even the use of explosives for "dynamic entry" through the doors. R.U. Ready was used to teach law enforcement and military personnel special tactics. A catwalk across the ceiling allowed instructors to monitor students as they made their way through the building. The facility found a ready market, clients included a number of police officers who paid for the training out of their own pockets

Another event that caught the attention of Blackwater was the 2000 bombing of the destroyer Cole in Yemen. In response, Blackwater constructed a realistic mockup of a Navy vessel. In the fall of 2002 the company won a $35.7 million, five-year contract with the Navy to conduct two-week training sessions for Navy personnel on topics that included sentry duty, weapons use aboard a ship, and how to board, seize, and search another ship.

What led to the most significant spike in business for Blackwater were the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001, and the ensuing events. Not only would the training facilities find more use, the company would be called on to provide trained personnel to corporations, the U.S. government, and the U.S. military. Blackwater supplied independent contractors to Afghanistan and later to Iraq when the United States invaded the country in spring 2003. Among their tasks, Blackwater personnel served as the personal guard for Paul Bremer, the head of the civilian administration. The company mostly recruited by word of mouth, hiring from within the close-knit community of former SEALs, Green Berets, Army Rangers, and Delta Force Troops. As the war in Iraq settled into a long-term conflict, the demand for personnel increased and Blackwater had to branch out. Jackson told the British newspaper The Guardian in 2004, "We scour the ends of the earth to find professionals." The company also found recruits in the Currituck County sheriff's office, where a number of deputies went to work for Blackwater overseas, making as much money in a single month as they did in a year at home. In 2004 Blackwater made news when it recruited 60 former commandos and other members of Chile's military and flew them to North Carolina for training before deploying them elsewhere.

Modern day "free lancers" were known in international security circles as "operators." In 2004 The Virginian Pilot offered a glimpse of them in Iraq: "They are easy to spot in a landscape dominated by young, uniformed soldiers and the dark slender profiles of Iraqis. Operators tend to be muscled-up men in their 30s or 40s, wearing T-shirts, ball caps and wrap-around sunglasses. An automatic weapon is ever present, cradled in their beefy biceps." Operators tended to be loners who joined the military but grew bored with the regimen and frustrated by the bureaucracy and low pay. It was not the life for a married man. According to the Virginian Pilot, "A military husband occasionally goes off to war, but an operator is always heading somewhere dangerous. Turn down a job or two, and the phone stops ringing. Retirement and leave don't exist. ... Operators rarely discuss their families. ... More than just a soft spot to shield, families can doom a man in a war zone if he can't cut off his emotions."

The use of operators and the companies like Blackwater that supplied them were little known until March 4, 2004 when four Blackwater employees were leading a convoy of trucks to pick up kitchen equipment. According to the company, they were assured by men they believed were members of the Iraqi Civil Defense Corps that they would have safe and quick passage through the dangerous city of Falluja. Instead, the road was blocked, their escape route cut off, and the men were shot to death, burned, and mutilated. Their charred remains were dragged before cameras, the video broadcast around the world. In another well chronicled incident, in April 2005 six Blackwater personnel were killed when the helicopter they were riding in was shot down, apparently by rocket-propelled grenades.

The Falluja incident led to a spike in employment applications for Blackwater, fueled in large part out of a sense of revenge, but it also brought the use of private security firms by the military into public view. To critics of the practice, Blackwater became the face of the entire industry, although in reality there were scores of similar companies. Altogether they added about 15,000 men to the military forces stationed in Iraq. Critics charged that rapid growth in the private military industry was leading to inexperience and poorly trained units. Moreover, the cost of using such forces could be hidden from the public, and the personnel were not subject to the same kind of accountability as U.S. soldiers. Miscreants were simply shipped home. Given that U.S. forces were stretched thin, however, the military had little choice but to continue to rely on private contractors. Following the events in Falluja, according to Nation magazine, Blackwater "hired the Alexander Strategy Group, a PR firm with close ties to GOPers like [House Majority Leader Tom] DeLay. By Mid-November the company was reporting 600 percent growth. In February 2005 the company hired Ambassador Cofer Black, former coordinator for counterterrorism at the State Department and former director of the CIA's Counterterrorism Center, as vice chairman."

Blackwater continued to see training as its core mission and made major upgrades to its North Carolina facilities. In 2004 the company received permission from Currituck County to expand operations into that county, including firearms ranges, parachute landing zones, and explosives training. Later in the year Blackwater began to build a roadway through 90 acres of its property that would be suitable for training in high-speed chases (above 100 miles per hour) as well as motorcade protection against terrorist attacks.

Blackwater was again in the news in the autumn of 2005 when about 150 Blackwater men were spotted in New Orleans during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, which devastated the city. Not only did they--along with operators from other firms--secure government facilities, they guarded private businesses and homes. The company also lobbied in 2005 for Homeland Security contracts to train 2,000 new Border Patrol agents. Jackson testified before Congress regarding the business and made a pitch for Blackwater as a one-stop shopping solution for the government. There was every reason to believe that because of military limitations and the company's strong political ties Blackwater, despite the notoriety it had received, was well positioned to prosper in the years to come.

Blackwater: Shadow Army

Blackwater USA is the most comprehensive professional military, law enforcement, security, peacekeeping, and stability operations company in the world.

http://www.blackwaterusa.com/

Blackwater USA was a participant or observer in the following events:

http://www.cooperativeresearch.org/entity.jsp?entity=blackwater_usa_1

Erik Prince (born June 6, 1969 in Holland, Michigan) is the founder and owner of the military support contractor Blackwater USA. A millionaire and former US Navy SEAL, after high school he briefly attended the United States Naval Academy before attending and graduating from Hillsdale College. After college, he earned a commission in the United States Navy after joining in 1992, and served as a Navy SEAL officer on deployments to Haiti, the Middle East and the Mediterranean, including Bosnia. When his father Edgar Prince unexpectedly died in 1995, he ended his Navy service prematurely. After Erik's mother, Elsa Prince, sold the family's automobile parts company, Prince Corporation, for $1.3 billion to Johnson Controls, Inc., Erik moved to Virginia Beach and personally financed the formation of Blackwater USA at the age of 27.

Prince is the brother of Betsy DeVos, a former chairman of the Republican Party of Michigan and wife of former Alticor (Amway) president and Gubernatorial candidate Dick DeVos.

Prince's first wife, Joan Nicole Prince, died of cancer in 2003, and he has since remarried and has six children. He now runs Prince Group, Blackwater's parent company, from an office in McLean, Virginia and also serves as a board member of Christian Freedom International, a nonprofit group with a mission of helping "Christians who are persecuted for their faith in Jesus Christ".

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erik_Prince

Q&A: Blackwater's founder on the record

http://content.hamptonroads.com/story.cfm?story=107985&ran=89575

Erik Prince, the founder of Blackwater USA, is famously media-shy. But the former Navy SEAL agreed to an e-mail interview with The Virginian-Pilot. Here’s the complete text:

Q. Can you tell me a little about your personal history? I know you were a SEAL. When was that? Is that what brought you to the Hampton Roads area? How long did you live in Virginia Beach?

A. I was raised in Holland, Mich. My dad was a very successful entrepreneur. From scratch he started a company that first produced high pressure die-cast machines and grew into a world-class automotive parts supplier in west Michigan. They developed and patented the first lighted car sun visor, developed the car digital compass/thermometer and the programmable garage door opener.

Not all their ideas were winners. Things like a sock-drawer light, an automated ham de-boning machine and a propeller driven snowmobile didn’t work out so well for the company. My dad used them as examples of the need for perseverance and determination.

I earned my pilot’s license at 17 and entered the Naval Academy after high school intending to be a Navy pilot. I didn’t like the academy but loved the Navy. This is where I was first exposed to the SEAL teams. I resigned after three semesters at the academy and attended Hillsdale College in Michigan, where I graduated in 1992. I re-entered the Navy through Officer Candidate School and was commissioned a naval officer. I then joined the SEALs, where I served as an officer at SEAL Team 8. I deployed to Haiti, the Middle East and the Mediterranean, including Bosnia.

As I trained all over the world, I realized how difficult it was for units to get the cutting-edge training they needed to ensure success. In a letter home while I was deployed, I outlined the vision that is today Blackwater.

I lived in Virginia Beach for about five years.

Q. Can you tell me a little about the genesis of Blackwater? What was your motivation in starting the company? Did you have any inkling that it would come so far so fast?

A. Just prior to a deployment, my dad unexpectedly died. My family’s business had grown to great success and I left the Navy earlier than I had intended to assist with family matters. I wanted to stay connected to the military so I built a facility to provide a world-class venue for U. S. and friendly foreign military, law enforcement, commercial, and government organizations to prepare to go into harm’s way. Many special operations guys I know had the same thoughts about the need for private advanced training facilities. A few of them joined me when I formed Blackwater. I was in the unusual position after the sale of the family business to self-fund this endeavor.

Q. How do you account for the phenomenal growth of Blackwater and the private security industry? Do you expect this growth to continue?

A. Blackwater's growth is due to a few simple, but important facts: We have always delivered our services complete, correct, and on time, and we continue to attract committed professionals who value service over self and who want to have an immediate positive impact for our customers.

Growth in this industry is not restricted to Iraq alone. Because of the demand, the companies who have continually invested for the long-term will be the companies who are looked at to provide services whenever they are needed. As I said before, when Blackwater got started there was little focus on training and readiness in individual skills.

We have a very long-term view to our work. We see ourselves assisting in the transformation of the DoD into a faster more nimble organization. The private sector has always led innovation in our country. If the government sees some of the things we are doing, and chooses to utilize us or to adopt and adapt some of our innovations in the defense of the nation, then all the better.

Q. Can you discuss the role played by Blackwater and other contractors in the Pentagon’s “total force,” as referenced in the latest Quadrennial Defense Review? What is its significance for Blackwater?

A. The "total force" refers to all resources available to be used in the nation's defense. Blackwater considers itself a partner to the DoD and all government agencies, and we stand ready to provide surge capacity, training, security and operational services in various areas at their request. We are honored to contribute in some small way.

American history details the contributions of private contractors in the development of our Nation. Examples include the Jamestown, Plymouth, and Massachusetts Bay colonies; all started as private investment endeavors whose security was provided by PMCs. Across the street from the White House is Lafayette Park; on its four corners stand statues of Lafayette, Von Steuben, Rochambeau, and Kosciusko. All were foreign professional military officers that came here to help build and develop the capacity of the Continental Army. The base of one of the statues bears the inscription: “He gave military training and discipline to the citizen soldiers who achieved the independence of the United States.” Lewis and Clark’s expedition to explore the American West consisted of some active duty soldiers but their “Corps of Discovery” crew also consisted of what would now be considered contractors.

Q. What are the economics of this industry? How is it cost-effective for the government to outsource these functions?

A. Blackwater and the private sector are able rapidly to tailor a custom solution to solve the customer’s problem. Our ability to quickly react with a right-sized solution whose entire cost is only associated with the duration of the contract is cost-effective because there are no subsequent carrying costs like salary, medical care, retirement, etc.

My family’s business was automotive supply, one of the most efficient and globally competitive in the world. You wake up in the morning having to drive efficiency throughout the organization or you will be driven under. We strive for that level efficiency in what we do today. In very competitive industries, the purchasing/contract officers understand your business as well as you do. The government can ensure good value for the taxpayer by pushing that level of competence and accountability to its purchasing agents and contracting officers too.

Q. There have been calls for more regulation of this industry. Do you agree that any further regulation is needed? If so, what could you support?

A. Given the sensational tone of the media coverage our industry receives, it is understandable that there are calls for more regulation. We certainly agree that our industry should be accountable and transparent, but we should carefully analyze the domestic and international regulations that already exist so that further conversations can be had from a common foundation of accurate information. There are already many tools at the disposal of purchasing agents, government contracting officers and law enforcement officials to ensure proper behavior of PMC’s. For example, early privateers (the forbearers of the U.S. Navy) would post a significant performance bond to receive their Letter of Marque. We fully support high standards with high enforcement that drive unethical, immoral players from our industry.

Q. Some contractors have been involved in financial or abuse scandals. How can that kind of thing be avoided?

A. Those companies or individuals who disregard the moral, ethical, and legal high ground are not long for this industry. Closely working together with contracting agencies, contracting officers, and policy makers can only reduce the opportunities for financial and other abuses. The key to success is leadership and balance; strong corporate governance, and operational and "field” leadership at all levels carries the day always. We want to reduce opportunities for abuse without constraining the flexibility that makes our industry so valuable.

Iraq Facts

http://www.iraqfact.com/zPic_blackwater.html

On March 31, 2004, four American civilian contractors were

killed by a grenade in Fallujah, Iraq. The bodies of the contractors were

burned and hung from a bridge. Then in a scene reminiscent of Mogadishu,

Somalia, the corpses were beaten and dragged through the streets. At the

time the civilian contractors were portrayed in the media as American

workers helping Iraqis rebuild their country, however, in reality they

were ex-Navel Seal, para-military security forces working for a firm called

Blackwater USA, and were on an intelligence gathering mission

Blackwater Security Consulting, whose four employees were viciously killed and

mutilated by a mob in Fallujah, Iraq, is one of a growing number of private security

contractors that are hiring military veterans for jobs previously assigned to the

military. 15,000 private security agents from the United States, Britain and

countries as varied as Nepal, Chile, Ukraine, Israel, South Africa and Fiji were

employed in Iraq during the time of the attack. There are around 25 different

security firms operating in Iraq performing tasks ranging from training the country's

new police and army to protecting government leaders to providing logistics for

the U.S. military. (2)

In March of 2004, it was reported that Blackwater had flown a group of about 60

former Chilean commandos, many of who had trained under the military

government of Augusto Pinochet, from Santiago to its training camp in North

Carolina. From there they were taken to Iraq.

In an interview with the Chilean newspaper La Tercera, a former Chilean army

officer, Carlos Wamgnet, 30, who was going to Iraq, said: "We are calm. This mission

is nothing new for us.

"In the end, this is an extension of our military career."

John Rivas, 27, a former Chilean marine, said the work in Iraq would provide a "very

good income" that would allow him to support his family.

"I don't feel like a mercenary," he added. (3)

According to Gary Jackson, President of Blackwater USA,

"We scour the ends of the earth to find professionals - the Chilean

commandos are very, very professional and they fit within the Blackwater

system." he added, "We have grown 300% over each of the past three years

and we are small compared to the big ones'

"We have a very small niche market, we work towards putting out the cream

of the crop, the best." (3)

The privatisation of security in Iraq has been growing as the US seeks to reduce

its commitment of troops. Since private companies pay experienced special forces

personnel far more than the armed services, a decline in re-enlistment has

resulted amongst the most highly trained troops. This has created a cycle where

the private firms are continually taking over more duties once done by "regular"

military forces

According to Jackson,

"The US military has ... problems," he said. "If they are going to outsource

tasks that were once held by active-duty military and are now using private

contractors, those guys [on active duty] are looking and asking, 'Where is

the money? (3)

Reports of the number of "private contractors" operating in Iraq varies form 10 to

20 thousand. As of Sept. 2005, 269 had been killed in action. (4)

Questions have been raised about the nature in which this large force of paid

mercenaries operates. Members of these security companies are highly trained ex-

Special Forces personnel, many non-American, that do not have to adhere to the

rules of engagement that the conventional military sets forth in order to meet

international law. With salaries that can be as high as $1,000 a day, squads of

Bosnians, Filipinos, Israelis, and varies other foreign nationals from nearly every "hot

spot" in the world have been hired for tasks ranging from airport security to

protecting American and Iraqi leaders. There is further concern that the non-

American fighters loyalty to the parent company could supersede that of the

United States who they are in fact representing, creating a higher probability that

the United States’ image abroad will be tarnished.

Private Security Workers Living On Edge in Iraq

Downing of Helicopter Shows Heightened Risks

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A10547-2005Apr22.html

BAGHDAD -- Cruising toward Baghdad in the belly of a Spanish turboprop plane with a dozen other private security contractors from Blackwater USA, Rich, a 43-year-old former Navy commando, squinted out the window at the Euphrates River.

The Casa 212 dove 12,000 feet toward Baghdad airport in a drunken, corkscrew landing. A short while later, Rich was riding shotgun in the back of one of Blackwater's South African-made armored Mamba vehicles along the main highway to the capital, one of the most dangerous roads in Iraq.

"I like being some place where stupidity can be fatal, because here you work with people who think about their actions," said Rich, who asked for security reasons that only his first name be used. He and his colleagues voice disdain for what they consider the soft, even pampered lives of most Americans in a society he sums up as one that "puts warnings on coffee cups."

Rich is typical of the men drawn to Blackwater USA and scores of other private security firms now doing a booming business in Iraq. They're driven by money and a lust for life on the edge, but also by a self-styled altruism. Sporting blue jeans, wraparound sunglasses and big tattoos, they look the part of gun-slinging cowboys -- but most are experienced enough to know that a hot-dog attitude is the fastest way to get yourself and others killed.

With more hired guns in Iraq than in any other U.S. conflict since the 1991 Persian Gulf War, Rich and other armed contractors also admit their role is cloudy and controversial. They do shoot to kill, but they aren't legally considered combatants. U.S. military officials have expressed concern about violence in which the private contractors open fire. The contractors' mission is to protect the lives of individuals and cargo but not necessarily to support the broader interests of the U.S. counterinsurgency.

For more than a year now, Rich has traveled across Iraq, guarding the former U.S. occupation authority chief, L. Paul Bremer, and other high-ranking diplomats. He plans to make a career at Blackwater despite the fact that 18 of his close co-workers have now perished on the job, including two whose bodies were hung in Fallujah last March from what is now called Blackwater Bridge and six who were killed when a helicopter they were riding in was shot down outside Baghdad on Thursday.

Indeed, with an estimated 240 deaths among some 20,000 armed private security contractors in Iraq, Rich's work is as risky or riskier than that of the U.S. military, as firms such as Blackwater take on an unprecedented role in the Iraq war. Blackwater has an average of 1,300 employees on a given day, spread out over seven countries, the firm says. That number includes hundreds in Iraq.

"We have to be willing to go abroad to fight, to go after these guys here so my family at home can stay safe," Rich said. He left the Navy SEALs in the mid-1990s to save his marriage, he said. But after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, he said he felt compelled to leave the Virginia cell phone company he worked for and put his military skills to use.

Making Hay

As the Blackwater convoy sped down the airport highway, John "Tool" Freeman, a red-headed ex-Marine, was at the wheel of the lead Mamba, a high-riding, $70,000 armored vehicle designed to withstand antitank mines.

Used by the South African military in Angola, the vehicle is Blackwater's primary means of zipping State Department employees and other nations' diplomats to Baghdad's fortified Green Zone. For additional protection, the convoys are shadowed by helicopters with armed guards perched at the open doors scanning for potential attackers.

Freeman, of Portsmouth, Va., said he joined Blackwater after seeing some Marines on television during the invasion of Iraq in 2003. "I'd been missing it for a while," he recalled. "I said 'Man, I really need to get back into this.' " But with average pay of $500 to $600 a day, he said, the money was also a big draw for him and his buddies. He said he planned to work for Blackwater for three years to save up cash for retirement -- and a sailboat.

"Most of us have a plan -- it's like, make hay while the sun shines," he said.

Freeman blasted the Mamba's air-horn to force several Iraqi vehicles off the highway. "We beep the horn and flash the lights or push them off the shoulder to keep a buffer between us. Our main threat is the car bomb," he said, adding, "We've had cars cross three lanes of traffic to come after us."

In charge of the daily airport runs, Freeman studies military and private intelligence reports and maps the locations of attacks to look for patterns. He also videotapes the route and watches the tape later to look for possible threats he missed. Such precautions are necessary, private contractors say, as they become more frequent targets of insurgent attacks.

"We're seeing personal security teams are getting hit more," said Richard Hicks, Blackwater's operations manager in Baghdad. "There's been a definite increase in attacks, to hit us where it hurts the most."

At the same time, Hicks said, contractors are under pressure to curb their aggressive methods, although they lack the firepower and backup enjoyed by the U.S. military. Early in the Iraq conflict and up until last year, "there were no rules" limiting contractors' use of force in Iraq, Hicks said. More recently, the State Department imposed restrictions discouraging the contractors from firing warning shots. There are still daily reports of contractors running Iraqis off the road or injuring or killing innocent people, he said.

"Now it's all about accountability," he said at Blackwater's Baghdad team house in the Green Zone, not far from the crossed-sabers archway, a symbol of the era of ousted president Saddam Hussein.

On Their Own

At the team house, the large, comfortable, but simple home of a former Baath Party member, Blackwater employees relax in the evening, eating home-cooked meals of stuffed tomatoes, chicken or hamburgers prepared by an Iraqi staff. Unlike the U.S. military, Blackwater has a far smaller logistical support system and purchases food and other supplies directly from Iraqi sources.

Employees of Blackwater, based in Moyock, N.C., and other private security firms said they were more flexible, efficient and, in many cases, more experienced than U.S. military forces in Iraq. With many of their members former Navy SEALs or Army Green Berets, their teams are small, tight-knit and responsive both by choice and necessity -- if they get in a tough spot, they can't depend on U.S. troops to come to their aid, they say.

Many recalled an incident in April 2004 when eight Blackwater employees fought off a major insurgent assault on the U.S. government compound in Najaf by the militia of the radical Shiite cleric Moqtada Sadr. Blackwater pilots flew in ammunition and evacuated the wounded without any U.S. military support, they said.

Rich and others said they were frequently fired upon by U.S. soldiers and Marines at checkpoints. "I've been shot at numerous times by our troops, and that's in a black Suburban with American flags," Rich said. Still, they say cooperation with the U.S. military on the ground is largely positive and voiced sympathy for the far younger, low-paid U.S. servicemen, who they say regularly approach them asking about jobs at Blackwater.

Vetting for Blackwater hires is rigorous, said Hicks, a former police chief in Pennsylvania. While the money was a key reason he joined, he said, "Once you get here the money isn't really an issue, because you could be dead the next day."

At the Bristol Hotel in Amman, Jordan, where Blackwater employees transit to and from Iraq, J.D. Stratton, a burly company manager, said 10 percent of Blackwater hires may be unqualified "chuckleheads" who just happen to make it through the screening.

"But they'll eventually be caught," said Stratton, whose nickname is "Terminator" because it is his job to dismiss those who don't work out. "If I show up at your doorstep, you are out of there," he said.

Alcohol abuse and a defiant attitude tend to be the main reasons people are fired, he said, relaxing with other employees at Harry's Jazz Bar. "You have to be disciplined to do this job. If any one of them is a cowboy he will . . . get everyone killed."

Blackwater Heavies Sue Families of Slain Employees for $10 Million in Brutal Attempt to Suppress Their Story

http://www.alternet.org/waroniraq/53460/

The lawyers representing the families of four American Blackwater contractors killed in Fallujah make the case that the company's executives are suing the families to keep them quiet and to avoid any accountability.

The following article is by the lawyers representing the families of four American contractors who worked for Blackwater and were killed in Fallujah. After Blackwater refused to share information about why they were killed, the families were told they would have to sue Blackwater to find out. Now Blackwater is trying to sue them for $10 million to keep them quiet.

Raleigh, NC -- The families of four American security contractors who were burned, beaten, dragged through the streets of Fallujah and their decapitated bodies hung from a bridge over the Euphrates River on March 31, 2004, are reaching out to the American public to help protect themselves against the very company their loved ones were serving when killed, Blackwater Security Consulting. After Blackwater lost a series of appeals all the away to the U.S. Supreme Court, Blackwater has now changed its tactics and is suing the dead men's estates for $10 million to silence the families and keep them out of court.

Following these gruesome deaths which were broadcast on worldwide television, the surviving family members looked to Blackwater for answers as to how and why their loved ones died. Blackwater not only refused to give the grieving families any information, but also callously stated that they would need to sue Blackwater to get it. Left with no alternative, in January 2005, the families filed suit against Blackwater, which is owned by the wealthy and politically-connected Erik Prince.

Blackwater quickly adapted its battlefield tactics to the courtroom. It initially hired Fred F. Fielding, who is currently counsel to the President of the United States. It then hired Joseph E. Schmitz as its in-house counsel, who was formerly the Inspector General at the Pentagon. More recently, Blackwater employed Kenneth Starr, famed prosecutor in the Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky scandal, to oppose the families. To add additional muscle, Blackwater hired Cofer Black, who was the Director of the CIA Counter- Terrorist Center.

After filing its suit against the dead men's estates, Blackwater demanded that its claim and the families' existing lawsuit be handled in a private arbitration. By suing the families in arbitration, Blackwater has attempted to move the examination of their wrongful conduct outside of the eye of the public and away from a jury. This comes at the same time when Congress is investigating Blackwater.

Over 300 contractors have been killed in Iraq with very little inquiry into their deaths. The families claim that Blackwater is attempting to cover up its incompetence, its cutting of corners in favor of higher profits, and its over billing to the government. Due to lack of accountability and oversight, Blackwater's private army has been able to obtain huge profits from the government, utilizing contacts established through Erik Prince's relationships with high-ranking government officials such as Cofer Black and Joseph Schmitz.

In addition to assembling its litigation troops, Blackwater also stonewalled the families concerning any information about how the men were killed. Over the past two and a half years, Blackwater has not responded to a single question or produced a single document. When the families' attorneys, Callahan & Blaine, obtained a Court Order to take the deposition of a former Blackwater employee with critical information about the incident, Blackwater quickly re-hired him and sent him out of the country. When the witness returned to the United States more than a year later, the families obtained another Court Order for his deposition. Blackwater again prevented them from taking his deposition by seeking the assistance of the U.S. Attorney's Office to block the deposition under the guise that he possibly possessed national secrets. Following an investigation, the U.S. Army reported that the witness had no secret information and that it had no objection to the deposition.

Blackwater has now lifted this atrocity to a whole new level by going on the offensive and suing the families for $10 million. The families now find themselves looking down the barrel of a gun as Blackwater, armed with a war chest and politically-connected attorneys, is aggressively litigating against them. Blackwater has also threatened to hold the administrator of the estates personally liable to scare him into abandoning his position, and has threatened the families' attorneys as well.

The families are simply without the financial wherewithal to defend against Blackwater. By filing suit, Blackwater is trying to wipe out the families' ability to discover the truth about Blackwater's involvement in the deaths of these four Americans and to silence them from any public comment. In February, the families testified before Congress.

However, Blackwater's lawsuit now seeks to gag the family members from even speaking about the incident or about Blackwater's involvement in the deaths. This is a direct attack to their free speech rights under the First Amendment.

"I initially took this case because it was the right thing to do in helping the families find closure by discovering the events surrounding their loved ones deaths, " said Daniel J. Callahan, attorney for the families. "I have found the evidence concerning Blackwater's involvement in the deaths to be overwhelming and appalling. Even more disturbing though is the callous nature in which Blackwater has not only concealed the truth, but also outright sued to force the families to stop pursuing the case and to silence them." Blackwater has spent millions of dollars and hired at least five different law firms to fight the families, rather than meeting and addressing what should be Blackwater's top priority -- the safety and well being of the mothers, wives, and children left behind. Blackwater has said that it will not pay one red cent to assist or console the surviving families, but instead has counter sued for $10 million.

Without help, Blackwater will succeed in avoiding scrutiny for its conduct, escaping accountability for its actions, and silencing the families of the four Americans killed in Fallujah. A defense fund has been established by which the public is able to donate money to assist the families with litigation costs and expenses.

What exactly happened that day in Fallujah?

http://www.usatoday.com/news/world/iraq/2007-06-10-fallujah-deaths_N.htm

It is one of the Iraq war's grisliest photo images: the charred bodies of American civilians strung up on a bridge in Fallujah. Four private security contractors had been shot in an ambush in March 2004 and burned in their vehicles by an angry mob.

Three years later, the Fallujah attack is at the center of a legal battle that could prompt more government oversight of security contracting companies and determine the extent of their legal liability in the war zone.

The families of the slain men still don't know what happened that day when their loved ones were consumed by insurgent violence. They are suing Blackwater USA, the men's employer, for wrongful death in the hope that their questions will be answered.

The lawsuit is the most prominent in an emerging body of litigation surrounding the secretive world of private security contractors in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. As details about security operations are revealed in the court cases, pressure has intensified in Congress to regulate how armed contractors operate. The Fallujah lawsuit became part of a congressional hearing on Blackwater operations held by Rep. Henry Waxman, D-Calif., in February.

Legal experts say that more than a dozen lawsuits have been filed against contractors and that the Fallujah suit, filed in 2005, could have the biggest long-term impact on the industry.

"Blackwater has got to win this one to deter other suits," says Scott Silliman, director of the Center on Law, Ethics and National Security at Duke University Law School. "All the other private contracting companies are watching this case."

The lawsuit alleges that Blackwater sent Jerry Zovko, Scott Helvenston, Michael Teague and Wesley Batalona on a job with inadequate equipment and protection. The men were killed while escorting a convoy of three empty trucks to pick up kitchen equipment for a European food company. According to the lawsuit, the men should have been traveling in fully armored vehicles and should have had a guard in each vehicle acting as a rear gunner to protect them from attack.

Blackwater denies the allegations and has filed a $10 million counterclaim. It says the families violated employment contracts that prohibit the men or their estates from suing the company.

Blackwater is one of the largest in a labyrinth of private security companies that collectively have assembled an armed force more than a third the size of the U.S. military presence in Iraq, according to congressional testimony and industry figures. The companies employ nearly 50,000 security professionals who escort convoys, guard U.S. diplomats, provide arms training and perform other duties.

The four men killed in Fallujah are among more than 990 American contractors who have been killed in Iraq and Afghanistan as of March 31, according to Labor Department estimates. That's more than one-fourth of the death toll of U.S. troops. Among the dead: 27 contractors for Blackwater, company spokeswoman Anne Tyrell says.

Unlike the practice with military casualties, no official reports are made on the circumstances surrounding the deaths of civilian security contractors.

The families' lawsuit has provided the most complete and only public account of events leading up to the Fallujah attack. Neither a military investigation nor a company report has been made public.

Several family members said Blackwater executives told them they'd have to sue to obtain the company's review of the ambush.

"Imagine having the people so near and dear to your hearts killed … in a foreign country," Kathryn Helvenston-Wettengel, mother of one of the contractors, told Waxman's subcommittee. "And then have the employer tell you the details are confidential."

A growing civilian force

Private contractors, including cooks, truck drivers, translators, interrogators, and maintenance workers, have worked alongside American troops since the Revolutionary War. Since the Cold War ended and the U.S. military was downsized, the United States has become even more dependent on them.

In Iraq, the Bush administration has pushed the use of private contractors to an unprecedented level and assembled a civilian force of 126,000 people to support 146,000 U.S. troops, according to Defense Department and industry figures.

Private contractors often can finish jobs "better and faster" than the military, says Steve Schooner, an Army reservist and a law professor at George Washington University Law School in Washington, D.C., who specializes in government procurement law. "If you say, I need X now, they'll go out and hire more people, buy more trucks, get more planes."

A complication in the Iraq war, he says, is the heavy dependence on armed contractors. The government has no formal oversight policies that "embrace mercenaries," he says.

"We never made those decisions with arms-bearing contractors. The decisions in Iraq were, 'Holy moly, we don't have enough people, go get some people with guns.' "

Four years into the Iraq war, however, little is publicly known about what they do. Members of Congress complain that they have been unable to learn details about the nearly $4 billion spent so far on private security contractors.

"There's no visibility on these contractors," says Rep. Jan Schakowsky, D-Ill. "Meaning no clue how much money we're spending. They are carrying out mission-sensitive activities with virtually no oversight whatsoever."

Jeremy Scahill, an investigative journalist for The Nation magazine, and author of Blackwater: The Rise of the World's Most Powerful Mercenary Army, says that litigation may shed more light on contractor operations than Congress thus far has been able to. "The one place we might be able to get actual information about the operation of these companies is through the court system," he says.

But even opponents of the government's reliance on armed contractors say oversight is the job of Congress, not the courts.

"The concept of second-guessing tactical decisions in a combat situation is not a good one," says retired Marine colonel T.X. Hammes, an expert on insurgencies. "There is no way for a court to determine what information was available on the ground. It will establish a dangerous precedent."

In court papers, the companies say they were working for the government and therefore are subject to the same protections against lawsuits as the military, which cannot be sued for the deaths or injuries of its troops. Blackwater argues that the four families' lawsuit "unconstitutionally intrudes on the exclusive authority of the military of the federal government to conduct military operations abroad."

In the two years since it was filed, the Fallujah lawsuit has bounced between state and federal courts amid a jumble of claims and counterclaims.

Last month, U.S. District Judge James Fox in North Carolina ordered the families and Blackwater into arbitration, a non-public procedure that is designed to resolve disputes without a trial. The families have appealed Fox's order.

Blackwater does not comment on litigation, company spokeswoman Tyrell says. The families of the men are honoring a North Carolina state judge's request to avoid media interviews.

A company with clout

Blackwater was founded in 1997 by Erik Prince, a former Navy SEAL and son of a wealthy Michigan auto-parts supplier. The company, headquartered in Moyock, N.C., on a 7,000-acre compound, has deeply rooted political connections in Washington.

It counts former top CIA and Defense Department officials, including Cofer Black, former director of the CIA's counterterrorism center, and Joseph Schmitz, former Pentagon inspector general, among its executives. Blackwater's legal team once included Fred Fielding, now White House counsel, and now includes Kenneth Starr, the special prosecutor who investigated the Monica Lewinsky and Whitewater scandals during the Clinton administration.

If company executives represent Blackwater's military and national security prowess, the men ambushed in Fallujah were classic Blackwater contractors: highly skilled commandos with backgrounds in military special operations. Three were former Army Rangers: Batalona, 48, who lived with his wife on Hawaii's Big Island; Zovko, 32 and single, who lived near his immigrant parents in a Cleveland suburb; and Teague, 38, who lived with his family in Clarksville, Tenn.

Worked with Demi Moore

Helvenston, 38, of Oceanside, Calif., was an ex-Navy SEAL who had parlayed his expertise into a career as a Hollywood stuntman, according to court papers. He served as a consultant for the movie Face/Off, starring John Travolta and Nicolas Cage, and advised Demi Moore on how to act like a SEAL for her movie G.I. Jane.

The men earned $600 a day, court papers say. Teague wanted to bankroll his son's college tuition. Helvenston was hoping to solve financial problems that had forced him into bankruptcy in 2002. But their families told Congress that the men had also been drawn to the war by the cause.

Andrew Howell, Blackwater's general counsel, told Congress that the men were appropriately equipped on their mission to Fallujah. In her testimony, Scott Helvenston's mother disagreed.

"They did not have heavy machine weapons," Helvenston-Wettengel said. "They were not able to conduct a risk assessment of the mission. They did not have a chance to learn the routes before going on this mission. In fact, when Scott Helvenston asked for a map of the route, he was told: 'It's a little too late for a map now.' "

Contractors accused of firing on civilians, GIs

Huge private force operates in Iraq with little supervision or accountability

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/20231579/

There are now nearly as many private contractors in Iraq as there are U.S. soldiers — and a large percentage of them are private security guards equipped with automatic weapons, body armor, helicopters and bullet-proof trucks.

They operate with little or no supervision, accountable only to the firms employing them. And as the country has plummeted toward anarchy and civil war, this private army has been accused of indiscriminately firing at American and Iraqi troops, and of shooting to death an unknown number of Iraqi citizens who got too close to their heavily armed convoys.

Not one has faced charges or prosecution.

There is great confusion among legal experts and military officials about what laws — if any — apply to Americans in this force of at least 48,000.

Murky set of rules

They operate in a decidedly gray legal area. Unlike soldiers, they are not bound by the Uniform Code of Military Justice. Under a special provision secured by American-occupying forces, they are exempt from prosecution by Iraqis for crimes committed there.

The security firms insist their employees are governed by internal conduct rules and by use-of-force protocols established by the Coalition Provisional Authority, the U.S. occupation government that ruled Iraq for 14 months following the invasion.

But many soldiers on the ground — who earn in a year what private guards can earn in just one month — say their private counterparts should answer to a higher authority, just as they do. More than 60 U.S. soldiers in Iraq have been court-martialed on murder-related charges involving Iraqi citizens.

No prosecutions

Some military analysts and government officials say the contractors could be tried under the Military Extraterritorial Jurisdiction Act, which covers crimes committed abroad. But so far, that law has not been applied to them.

Security firms earn more than $4 billion in government contracts, but the government doesn’t know how many private soldiers it has hired, or where all of them are, according to the Government Accountability Office. And the companies are not required to report violent incidents involving their employees.

Security guards now constitute nearly 50 percent of all private contractors in Iraq — a number that has skyrocketed since the 2003 invasion, when then-Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld said rebuilding Iraq was the top priority. But an unforeseen insurgency, and hundreds of terrorist attacks have pushed the country into chaos. Security is now Iraq’s greatest need.

Efforts to boost accountability

The wartime numbers of private guards are unprecedented — as are their duties, many of which have traditionally been done by soldiers. They protect U.S. military operations and have guarded high-ranking officials including Gen. David Petraeus, the U.S. commander in Baghdad. They also protect visiting foreign officials and thousands of construction projects.

At times, they are better equipped than military units.

Their presence has also pushed the war’s direction. The 2004 battle of Fallujah — an unsuccessful military assault in which an estimated 27 U.S. Marines were killed, along with an unknown number of civilians — was retaliation for the killing, maiming and burning of four Blackwater guards in that city by a mob of insurgents.