Anabolic-androgenic steroids or AAS are a class of natural and synthetic steroid hormones that act on the balance between anabolic and catabolic processes within the body. AAS work by binding to androgen receptors of muscle cells which has the effect of increasing protein synthesis. This increased protein synthesis results in anabolism being favored over catabolism. The result of anabolism is growth and differentiation of several types of skeletal tissues, such as bone and especially in the cross-sectional area of muscle cells. In addition to anabolic effects, AAS also have androgenic properties, including the development and maintenance of masculine characteristics.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steroid

A group of synthetic hormones that promote the storage of protein and the growth of tissue, sometimes used by athletes to increase muscle size and strength.

http://www.answers.com/topic/anabolic-steroid

Anabolic steroids

http://espn.go.com/special/s/drugsandsports/steroids.html

There should not be a controversy over anabolic steroid use in athletics -- non-medical use of anabolic steroids is illegal and banned by most, if not all, major sports organizations. Still, some athletes persist in taking them, believing that these substances provide a competitive advantage. But beyond the issues of popularity or legality is the fact that anabolic steroids can cause serious physical and psychological side effects.

In light of these hazards, measures to curtail the use of anabolic steroids are escalating. One of the nation's foremost authorities on steroid use, Dr. Gary Wadler, is part of a concerted effort to educate the public about the dangers of anabolic steroids. Dr. Wadler, a New York University School of Medicine professor and lead author of the book Drugs and the Athlete, serves as a consultant to the U.S. Department of Justice on anabolic-androgenic steroid use. He has also won the International Olympic Committee President's Prize for his work in the area of performance-enhancing drugs in competitive sports. He joined us to address the issue of steroids and sports.

What are anabolic steroids?

Anabolic steroids -- or more precisely, anabolic-androgenic steroids -- are the synthetic derivatives of the naturally occurring male anabolic hormone testosterone. Both anabolic and androgenic have origins from the Greek: anabolic, meaning "to build," and androgenic, meaning "masculinizing." Testosterone's natural androgenic effects trigger the maturing of the male reproductive system in puberty, including the growth of body hair and the deepening of the voice. The hormone's anabolic effect helps the body retain dietary protein, which aids in the development of muscles. "Although there are many types of steroids with varying degrees of anabolic and androgenic properties, it's the anabolic property of steroids that lures athletes," says Dr. Wadler. "They take them to primarily increase muscle mass and strength."

How are steroids taken?

Steroids can be taken orally or they can be injected. Those that are injected are broken down into additional categories, those that are very long-lasting and those that last a shorter time. In recent years, use has shifted to the latter category -- shorter-lasting, water-soluble injections. "The reason for that is that the side effects associated for the oral form were discovered to be especially worrisome for the liver,"says Dr. Wadler. "But the injectable steroids aren't free of side-effects either. There is no free ride and there is a price to be paid with either form."

Who takes anabolic steroids and why?

It is not only the football player or weightlifter or sprinter who may be using anabolic steroids. Nor is it only men. White- and blue-collar workers, females and, most alarmingly, adolescents take steroids -- all linked by the desire to hopefully look, perform and feel better, regardless of the dangers.

Anabolic steroids are designed to mimic the bodybuilding traits of testosterone. Most healthy males produce less than 10 milligrams of testosterone a day. Females also produce testosterone but in minute amounts. Some athletes however, may use up to hundreds of milligrams a day, far exceeding the normally prescribed daily dose for legitimate medical purposes. Anabolic steroids do not improve agility, skill or cardiovascular capacity.

What are the health hazards of anabolic steroids?

"There can be a whole panoply of side effects, even with prescribed doses," says Dr. Wadler. "Some are visible to the naked eye and some are internal. Some are physical, others are psychological. With unsupervised steroid use, wanton 'megadosing' or stacking (using a combination of different steroids), the effects can be irreversible or undetected until it's too late." Also, if anabolic steroids are injected, transmitting or contracting HIV and Hepatitis B through shared needle use is a very real concern.

Additionally, Dr. Wadler stresses that "unlike almost all other drugs, all steroid based hormones have one unique characteristic -- their dangers may not be manifest for months, years and even decades. Therefore, long after you gave them up you may develop side effects."

Physical side effects

Men - Although anabolic steroids are derived from a male sex hormone, men who take them may actually experience a "feminization" effect along with a decrease in normal male sexual function. Some possible effects include:

Reduced sperm count

Impotence

Development of breasts

Shrinking of the testicles

Difficulty or pain while urinating

Women - On the other hand, women often experience a "masculinization" effect from anabolic steroids, including the following:

Facial hair growth

Deepened voice

Breast reduction

Menstrual cycle changes

With continued use of anabolic steroids, both sexes can experience the following effects, which range from the merely unsightly to the life endangering. They include:

Acne

Bloated appearance

Rapid weight gain

Clotting disorders

Liver damage

Premature heart attacks and strokes

Elevated cholesterol levels

Weakened tendons

Special dangers to adolescents

Anabolic steroids can halt growth prematurely in adolescents. "What happens is that steroids close the growth centers in a kid's bones", says Dr. Wadler. "Once these growth plates are closed, they cannot reopen so adolescents that take too many steroids may end up shorter than they should have been."

Behavioral side effects

According to Dr. Wadler, anabolic steroids can cause severe mood swings. "People's psychological states can run the gamut." says Wadler. "They can go from bouts of depression or extreme irritability to feelings of invincibility and outright aggression, commonly called "'roid rage. This is a dangerous state beyond mere assertiveness."

Are anabolic steroids addictive?

Recent evidence suggests that long-time steroid users and steroid abusers may experience the classic characteristics of addiction including cravings, difficulty in stopping steroid use and withdrawal symptoms. "Addiction is an extreme of dependency, which may be a psychological, if not physical, phenomena," says Dr. Wadler. "Regardless, there is no question that when regular steroid users stop taking the drug they get withdrawal pains and if they start up again the pain goes away. They have difficulties stopping use even though they know it's bad for them."

Anabolic steroids were developed in the late 1930s primarily to treat hypogonadism, a condition in which the testes do not produce sufficient testosterone for normal growth, development, and sexual functioning. The primary medical uses of these compounds are to treat delayed puberty, some types of impotence, and wasting of the body caused by HIV infection or other diseases.

http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/drugfact/steroids/index.html

During the 1930s, scientists discovered that anabolic steroids could facilitate the growth of skeletal muscle in laboratory animals. This led to abuse of these compounds by bodybuilders and weightlifters and then by athletes in other sports.1

Anabolic steroids can be taken orally, injected intramuscularly, or rubbed on the skin when in the form of gels or creams.2 These drugs are often used in patterns called cycling, which involves taking multiple doses of steroids over a specific period of time, stopping for a period, and starting again. Users also frequently combine several different types of steroids in a process known as stacking.3 By doing this, users believe that the different steroids will interact to produce an effect on muscle size that is greater than the effects of using each drug individually.4

Another mode of steroid use is "pyramiding." This is a process in which users slowly escalate steroid use (increasing the number of drugs used at one time and/or the dose and frequency of one or more steroids) reaching a peak amount at mid-cycle and gradually tapering the dose toward the end of the cycle.5

Extent of Use

Results from the 2006 Monitoring the Future Study, which surveys students in eighth, tenth, and twelfth grades, show that 1.6% of eighth graders, 1.8% of tenth graders, and 2.7% of twelfth graders reported using steroids at least once in their lifetimes.6

Percent of Students Reporting Steroid Drug Use, 2005-2006

8th Grade 10th Grade 12th Grade

2005

2006

2005

2006

2005

2006

Past month

0.5%

0.5%

0.6%

0.6%

0.9%

1.1%

Past year

1.1

0.9

1.3

1.2

1.5

1.8

Lifetime

1.7

1.6

2.0

1.8

2.6

2.7

Regarding the ease by which one can obtain steroids, 17.1% of eighth graders, 30.2% of tenth graders, and 41.1% of twelfth graders surveyed in 2006 reported that steroids were "fairly easy" or "very easy" to obtain. Furthermore, 60.2% of twelfth graders surveyed reported that using steroids was a "great risk” during 2006.7

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also conducts a survey of high school students throughout the United States, the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS). Nearly 5% of all high school students surveyed by CDC in 2005 reported lifetime use of steroid pills/shots without a doctor's prescription.8

Percent of Students Reporting Lifetime Steroid Use, 2001–2005

2001 2003 2005

9th grade 5.8% 7.1% 4.8%

10th grade 4.9 6.1 3.9

11th grade 4.3 5.6 3.7

12th grade 4.3 4.9 3.3

Total 5.0 6.1 4.0

Approximately 1.9% of young adults (ages 19–28) surveyed in 2005 reported lifetime use of steroids.9

Percent of Young Adults Reporting Steroid Use, 2004–2005

2004 2005

Past month 0.1% 0.1%

Past year 0.5 0.5

Lifetime 1.8 1.9

Top

Health Effects

Anabolic steroid abuse has been associated with a wide range of adverse side effects ranging from some that are physically unattractive, such as acne and breast development in men, to others that are life threatening. Most of the effects are reversible if the abuser stops taking the drug, but some can be permanent. In addition to the physical effects, anabolic steroids can also cause increased irritability and aggression.10

Some of the health consequences that can occur in both males and females include liver cancer, heart attacks, and elevated cholesterol levels.11 In addition to this, steroid use among adolescents may prematurely stop the lengthening of bones resulting in stunted growth.12

People who inject steroids also run the risk of contracting or transmitting hepatitis or HIV.13 Some steroid abusers experience withdrawal symptoms when they stop taking the drug. These withdrawal symptoms include mood swings, fatigue, restlessness, loss of appetite, insomnia, reduced sex drive, and depression. This depression can lead to suicide attempts, and if left untreated, can persist for a year or more after the abuser stops taking the drugs.14

Top

Production & Trafficking

Illicit anabolic steroids are often sold at gyms, competitions, and through mail operations after being smuggled into this country.15 The most common sources for obtaining steroids for illegal use are Internet purchases and smuggling them into the U.S. from other countries such as Mexico and European countries. These countries do not require a prescription for the purchase of steroids, making it easier to smuggle them.16 In addition to this, steroids are also illegally diverted from U.S. pharmacies or synthesized in clandestine laboratories.17

Legislation

Concerns over a growing illicit market and prevalence of abuse combined with the possibility of harmful long-term effects of steroid use led Congress to place anabolic steroids into Schedule III of the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) in 1991.18 It is therefore illegal to possess or sell anabolic steroids without a valid prescription. Some States have also implemented additional fines and penalties for illegal use of anabolic steroids.19

The International Olympic Committee, National Collegiate Athletic Association and many professional sports leagues (including the Major League Baseball, National Basketball Association, National Football League, and National Hockey League), have banned the use of steroids by athletes due to their potentially dangerous side effects and because they give the user an unfair advantage.20

Street Terms

Street/Slang Terms for Steroids

Arnolds

Gym Candy

Juice

Pumpers

Stackers

Weight Trainers

Mitchell to Open Steroid Interviews Soon

http://www.casperstartribune.net/articles/2007/05/07/ap/sports/baseball/d8ou4b9o1.txt

NEW YORK - Former Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell said he expects interviews with active players to begin promptly as part of his investigation into steroids in baseball.

Mitchell sent a letter to the players' association in late March requesting the interviews, which the union confirmed April 3. Lawyers for the union, commissioner's office and Mitchell's staff met later in April to discuss possible interviews, along with Mitchell's request for medical records.

"In the course of our work, we have gathered thousands of pages of documents and conducted hundreds of interviews of individuals with current or past connections to professional baseball, including many former players," Mitchell said Friday in an e-mail to The Associated Press.

"I have just recently requested that interviews of current players begin promptly, which is one of the final phases of our investigation. We expect to meet soon with the players whose interviews we have requested, but to the extent that we are not able to, we will deal with the issue at that time."

Mitchell also may gain evidence that federal prosecutors have gathered in their case against former New York Mets bat boy Kirk Radomski, The Washington Post reported Friday.

Radomski, who pleaded guilty to felony charges of distributing steroids and laundering money, has agreed to cooperate with the ongoing federal steroids investigation, as well as Mitchell's inquiry.

The 37-year-old has admitted providing steroids, human growth hormone, amphetamines and other drugs to "dozens of current and former Major League Baseball players and associates," U.S. Attorney Scott Schools said in a statement.

"Are documents, etcetera, going to be turned over?" Assistant U.S. Attorney Matt Parrella was quoted as saying by the Post. "That's part of the concept, but I can't lay out a schedule or roster of documents. We will make an evaluation item by item."

Mitchell also wouldn't specify what data he hopes to receive.

"I am committed to completing the remaining work and to issuing the report as soon as possible," he said in Friday's e-mail to the AP. "With regard to Mr. Radomski, I have stated that we look forward to working with federal law enforcement toward our shared goal of dealing effectively with illegal performance-enhancing drug use in baseball. Our work in that regard is only one aspect of the broader effort in this investigation."

Confessed steroids dealer could hold key

http://www.usatoday.com/sports/baseball/2007-04-30-steroids-clubhouse-worker_N.htm

Kirk Radomski was just an ordinary New York Mets clubhouse attendant. He washed uniforms. Wiped and polished baseball cleats. Fetched sandwiches.

Now, 12 years later, he has one last errand.

He is being asked to deliver a powerful blow to the integrity of Major League Baseball, which he claims could destroy reputations and embarrass some of the game's biggest stars.

Radomski, 37, pleaded guilty Friday to being a steroid dealer to dozens of major leaguers for 10 years and has been secretly assisting the federal government for the past 16 months in its steroid probe.

Radomski, who bragged his revelations could be more damaging than former slugger Jose Canseco's 2005 book, signed a plea agreement requiring he cooperate with the federal government. He not only will testify before grand juries and trials in future cases, but also vowed to assist MLB's steroids investigation, conducted by former Sen. George Mitchell.

FIND MORE STORIES IN: Major League Baseball | Mets | Kirk Radomski | Jeff Novitzky | Marc Mukasey | Sen. George Mitchell

"The players have been enormously lucky up until now," said attorney Marc Mukasey, a former federal prosecutor who oversaw dozens of steroid-trafficking cases for the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of New York. "The information that has been leaked to the public has been relatively narrow.

"BALCO (Bay Area Laboratory Co-Operative) was sort of like the water building up to the dam, and at some point, you knew the dam was going to break. That dam is breaking."

Lots of access to players

Radomski, who worked with the Mets from 1985 to 1995, has plenty of evidence, according to court records. He told government authorities he distributed anabolic steroids and other performance-enhancing drugs from 1995 to 2005 to dozens of current and former major leaguers.

"We are encouraged that the U.S. attorney has insisted Mr. Radomski cooperate with Sen. George Mitchell's investigation as a condition of the plea agreement," said Bob DuPuy, president of Major League Baseball. "We urge all personnel connected with Major League Baseball to come forward with whatever information they may have that will assist Sen. Mitchell in his investigation."

Radomski, according to court records, was a major drug source for players. He has been cooperating with prosecutors since his Long Island, N.Y., home was raided on Dec. 14, 2005. The undercover investigation was led by IRS investigator Jeff Novitzky, the lead agent in the BALCO steroids case.

"During my past employment with Major League Baseball," Radomski said in his plea agreement, "I developed contacts with Major League Baseball players throughout the country to whom I subsequently distributed anabolic steroids and athletic performance-enhancing drugs.

"I distributed anabolic steroids and other performance-enhancing drugs, including human growth hormone and Clenbuterol, as well as amphetamines. I deposited the payments for those anabolic steroids into my personal bank account, and I then used the proceeds to finance my residence, which was the base of operation, warehouse, and communications center for my anabolic steroid-dealing business."

Outfielder Brian McRae played for the Chicago Cubs from 1995 to 1997 and for the Mets from 1997 to 1999. He said he remembers seeing Radomski in the visiting and home clubhouses.

"Let's just say I saw a lot of people coming and going from the clubhouse that had no business being there," McRae said. "It led me to believe there was some shady s—- going on. The clubhouse was an open door with people coming in and out at all times. You'd ask yourself, 'What the hell are they doing here?'

"There was too much access. During that time, and what was going on in the game, it was easy for guys to bring stuff in.

"You didn't know exactly who was doing what, but you knew the best way to do something like that is through the clubhouse kids."

Supplier will cooperate in all inquiries

Novitzky, according to court records, was tipped off by the FBI in February 2005 that Radomski was providing steroids and other illegal performance-enhancing drugs to players. They made their case Dec. 7, 2005, when he shipped two vials of the steroid Deca-Durabolin, two vials of testosterone and 10 syringes to San Jose, Calif. Radomski believed the shipment was going to the friend of a former client; it went to an undercover agent.

Radomski's home was raided a week later. Federal authorities uncovered "thousands of doses of numerous types of anabolic steroids in both pill and injectable form." They also found players' cellphone numbers, shipping records, financial records, correspondence and contact lists that detailed Radomski's distribution to players.

Radomski was considered by the government as the chief supplier of baseball's illegal performance-enhancing drugs after BALCO was shut down in 2003. He pleaded guilty to one count of distributing steroids and one count of money laundering and faces up to 25 years in prison and $500,000 in fines. Sentencing is scheduled for Sept. 7.

"This kid will continue to cooperate, tell names, tell stories, recall events, and will do that against as many people as possible to bring himself the most leniency," Mukasey said. "This thing could take five years."

The Radomski sting is the second the government has made public since the BALCO case started in September 2003. The Arizona Diamondbacks' Jason Grimsley was served with a search warrant nearly six months after Radomski was nabbed in April 2006 when the pitcher received shipments of HGH.

Grimsley stopped cooperating with the government after his original affidavit identified at least six current players who were also receiving illegal performance-enhancing drugs. The names were blacked out in the court documents, just as they are in Radomski's search warrant filed by Novitzky.

The difference is the players identified by Radomski were provided to Mitchell. The former senator could provide the names to Commissioner Bud Selig, giving him the option to reveal the identities.

The players' identities may also be revealed if Radomski is asked to testify in a grand jury investigation. Congress could also issue subpoenas and force prosecutors to provide the names.

"The distribution of anabolic steroids to professional athletes cheats both the paying public and the clean athletes and is a serious crime," U.S. Attorney Scott Schools said. "This investigation shows that distribution of performance-enhancing drugs continues to be an issue for sport in America. This office is dedicated to pursuing those who benefit from such crimes."

Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., who led the steroid hearings in 2004, also is trying to persuade the players union to cooperate with Mitchell's inquiry. No player has publicly agreed to be interviewed by Mitchell.

"You'll probably see more congressional hearings, if the initial stories are true," McCain said Saturday during a campaign stop.

There's more to be revealed

Radomski listed his occupation as a "personal trainer," according to his tax returns, and received more than $34,000 from 23 checks in May 2003 to March 2005. He also shipped steroids twice in 2005 to clients in the Bay Area, and according to court documents, one player was also involved in the BALCO case.

San Francisco Giants slugger Barry Bonds, New York Yankees DH Jason Giambi, Detroit Tigers DH Gary Sheffield and four other players testified in 2003 before a federal grand jury investigating BALCO.

Bonds and Sheffield denied knowingly using banned drugs, but Bonds still is being investigated by the federal government on possible perjury charges.

Greg Anderson, Bonds' personal trainer, pleaded guilty to steroid dealing in the BALCO case and has been imprisoned since November for refusing to testify to a grand jury investigating Bonds.

"It sounds like this kid is going to do way more to break open this problem than (BALCO founder) Victor Conte ever did," Mukasey said. "That's for damn sure."

Lawmakers go after steroids

http://www.myfoxtampabay.com/myfox/pages/News/Detail?contentId=3093113&version=1&locale=EN-US&layoutCode=TSTY&pageId=3.2.1

TAMPA - Steroid testing is about to hit the playing field at high schools throughout Florida. Lawmakers are working on a plan to test athletes in three sports: wrestling, football, and baseball.

The dangers of steroid use are what state officials are trying to tackle.

National Football League defensive lineman Lyle Alzado died at 43 from excessive steroid use.

"They want it all. Everyone wants that million-dollar contract and it seems the attitude is 'I'll take the risk because if I succeed I'll out-distance everyone else,'" said personal trainer Dietrich Ricks. Competition is fierce and it trickles down to the high school level.

"Getting a division one major scholarship is a big deal for a lot of kids and it's worth thousands and thousands of dollars," said Plant High School athlete Derek Winter.

According to a state study, about 19,350 Florida students reported having used steroids. That represents about 1.4-percent of the total population.

"Our government, or us as coaches, or things of that sort, will help kids make the right decisions particularly when they don't have the vision of the forethought of something that could hurt them down the road," said Plant High School football coach Robert Weiner.

Any student who tests positive would be suspended from practice and games for 90 days. They couldn't return until their test comes back clean and would face regular testing for the rest of their high school careers.

Polk County already tests its athletes for steroid use. This measure could go into effect in July if it passes a final vote.

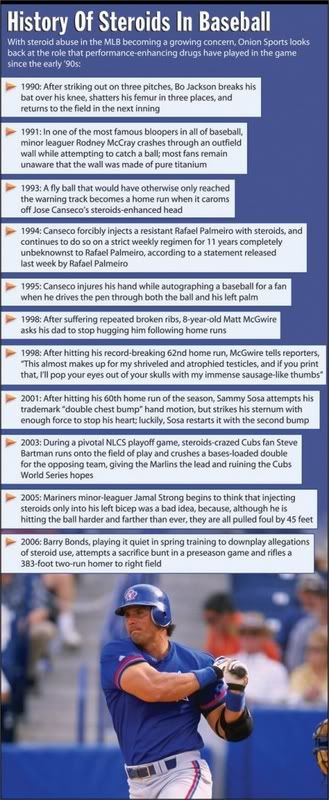

The Juice and I

Jose Canseco and steroids, a love story.

http://www.slate.com/id/2113745/

For those who have marveled at baseball's homoerotic rituals—the butt-slapping, the excessive man-hugs—let Jose Canseco, author of Juiced, add a more intimate encounter. Canseco claims that while he was playing for the Oakland A's in the late 1980s, he and teammate Mark McGwire would lock themselves in a bathroom stall and inject each other with steroids. Pause on that image for a moment. Canseco was 6 feet 4 inches and weighed in the neighborhood of 250 pounds; McGwire was 6 feet 5 inches and adding beef like an Arby's franchise—for the two of them to squeeze into a men's room stall must have presented something of a geometric challenge. Now imagine McGwire gently lowering his uniform pants while Canseco ("I'm a good injector") hovers over his derriere with a syringe, and add the fact that these men are enjoying this ritual immensely, even laughing about it, and there you have an enduring image of the Bash Brothers. Back, back, back, back, back—side!

Juiced is a mesmerizing book, and not just because Canseco throws off stories like that without a trace of self-regard. Canseco has pulled off the impossible: He has written a giddy testimonial to steroids. Perhaps the fact that he named his alleged co-juicers gulled sportswriters into thinking that Juiced was meant as a confessional. It reads more like a huckster selling long-life elixir at a rural county fair. "Steroids, used correctly, will not only make you stronger and sexier, they will also make you healthier," Canseco crows. "Certain steroids, used in proper combinations, can cure certain diseases. Steroids will give you a better quality of life and also drastically slow down the aging process." Then he helpfully adds, "I'm forty years old, but I look much younger."

The sports memoir usually relies on a heartbreaking premise: that playing sports is a wretched, dehumanizing job, and that the only way to survive is the daily intake of massive quantities of controlled substances. Canseco's book has all the substances but none of the morose style. It was his pre-steroid youth, Canseco argues, that was wretched and dehumanizing. In high school in Miami, he was a runty 5 feet 11 inches and 155 pounds, and too shy to stand up in front of the class. His father Jose Sr. humiliated him after every strikeout: "You're going to grow up and work at Burger King or McDonald's! You'll never add up to anything!" (His twin brother, Ozzie, barely seen here, suffered the same wrath. Perhaps Jose Sr. was half right.) It wasn't until Canseco was drafted in the 15th round by the Athletics, and watched his beloved mother die, that he decided to tune into steroids with the encouragement of a high-school friend he calls "Al." To Jose's great relief, Al, too, was a good injector.

Upon reaching the majors, Canseco proclaimed himself the "godfather" of steroids and set about evangelizing their glory to his teammates. "I probably know more about steroids and what steroids can do for the human body than any layman in the world," he boasts. For Canseco, steroids weren't just about padding his home run and RBI totals. Injecting was a near-religious experience. Steroids eased his degenerative disc disease and extended his life: "I needed steroids and growth hormone just to live," he writes. With the zeal of the converted, Canseco credits steroids with helping him avoid temptations, like hard liquor and amphetamines, and notes that the majors are a cleaner, more sober place since the drinking and pill-popping old-timers were replaced by the younger generation of 'roiders.

For Canseco, even steroids' most gruesome side effects have a silver lining. For example: "[O]ne definite side effect of steroid use is the atrophying of your testicles." Uh-oh. "But here's the point I want to emphasize: what happens to your testes has nothing to do with any shrinking of the penis. That's a misconception." Well, I suppose that's slightly less revolting. "As a matter of fact, the reverse can be true. Using growth hormone can make your penis bigger, and make you more easily aroused. So to the guys out there who are worried about their manhood, all I can say is: Growth hormone worked for me." Why, doctor, get me some steroids!

Steroids made Canseco into one of baseball's great playboys. He slept with, by his own estimation, a "couple hundred" women in 17 seasons in the majors—"but I'm not talking about outrageous numbers." Canseco would often select potential dates by inviting a few dozen women to his room for a "beauty contest"; the winners would be allowed to join him in public later that night. Even his monogamous relationships had a certain macho luster. He dated and married Miss Miami, divorced her, and then dated and married a Hooters girl. He flirted with Madonna, who invited him up to her Manhattan penthouse and sounded him out about marriage. (The New York Post dubbed him "Madonna's Bat Boy.")

In the hundreds of pages devoted to the wonders of steroids, Canseco chronicles a single moment of heartbreak. When his daughter Josie was still an infant, Canseco's estranged second wife Jessica, the Hooters girl, disappeared. He called a friend at "one of the airlines," who managed to track Jessica to Kansas City. When Canseco finally reached her, Jessica said she had left him for another jock: Tony Gonzalez, tight end for the Kansas City Chiefs. Canseco was grief-stricken. He walked to his bedroom closet and pulled out a Street Sweeper shotgun. Canseco says he used the gun to shoot sharks when he went deep-sea fishing—an image so comic that we'll put it aside for now. Anyway, Canseco had the Street Sweeper and was ready to do himself in when a tiny noise called him forth from despair. "Something had decided that it wasn't my time yet," he writes. Maybe it was his infant daughter. Maybe God. Or maybe—and this is just a hunch—it was the steroids, calling to save their champion.

There's a great memoir buried inside this half-great one, and it has nothing to do with steroids. Canseco, who was born in Cuba, was a rarity in 1988: a Latin baseball superstar. He's also the first Latin ballplayer to write an important memoir, and every page seethes with racial resentment. Canseco lashes the media for giving preferential treatment to white stars like McGwire and Cal Ripken Jr.—who he says behaved just as wretchedly as he did but were spared the public vilification. Seizing on his arrests for battery and weapons possession, the media portrayed him as an out-of-control Cuban lout. "They always depicted me as the outsider, the outlaw, the villain. I was never ushered into that special club of all-American sports stars. … After all, I was dark." For all the miracles steroids performed on Canseco's body, that was the one thing Anadrol and Equipoise couldn't change.

Bonds Charges Toward Record With a Scandal Close Behind

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/02/sports/baseball/02bonds.html?em&ex=1178251200&en=100532add26ba5f7&ei=5087%0A

SAN FRANCISCO, May 1 — The San Francisco Giants gave their first public tribute to Barry Bonds before he played his first game with them.

It was December 1992, in downtown San Francisco, and thousands of people filled Union Square to see the Giants’ new slugger. The mayor was there. Willie Mays was there. Marjorie Wallace, a disabled fan who went to every home game, was there.

When Bonds took the microphone, he saw Wallace in the crowd, pointed to her, and wiped away a tear.

“That’s what I’ll remember from the first one,” said Larry Baer, the Giants’ executive vice president. “I feel like I’ve been planning Barry Bonds tributes ever since.”

The task has become more and more sensitive. Now that Bonds is up to 742 home runs, 13 shy of Hank Aaron’s career record, the Giants have started planning yet another celebration, while recognizing that not everyone will be cheering with them.

“It’s much weightier now,” Baer said. “We have to be respectful to everybody.”

The more home runs Bonds hits, the hotter baseball’s steroids controversy seems to burn. Last week, with Bonds in the midst of his latest power surge, the former Mets batboy Kirk Radomski testified in San Francisco to the federal grand jury that is investigating Bonds for perjury.

Bonds’s lawyer, Michael Rains, said that Bonds had nothing to do with Radomski, who admitted selling performance-enhancing drugs to dozens of current and former professional baseball players. But it was another case of Bonds and steroids linked in the limelight.

If Major League Baseball wanted Bonds to slink into obscurity this season, he has done just the opposite. Outside of the Yankees’ Alex Rodriguez, no hitter has been more impressive through the first month of the season.

With his former trainer still in jail and a grand jury still targeting him, Bonds entered Tuesday night batting .356 with eight home runs. He was leading the National League with a .536 on-base percentage and an .814 slugging percentage.

“What he’s doing, we’ve all seen it before,” said Bruce Bochy, the Giants’ manager.

On opening day, forecasters projected that Bonds would break Hank Aaron’s home run record sometime in midsummer. But with Bonds hitting a home run every three games, he is on pace to pass Aaron by the middle of June.

(Considering Bonds’s sense of drama, he may note that the Giants play the Red Sox at Fenway Park on June 15-17, and play the Yankees at AT&T Park on June 22-24.)

No matter whom Bonds is facing, the record-breaking blast will be remembered for its historical significance and its undeniable awkwardness. Aaron has said he will not be in attendance. Commissioner Bud Selig has not committed either way.

Bonds, uncharacteristically open this season, has said that he does not hold anything against Aaron and Selig. He also said that he was too far from the record for any kind of hype to begin.

Bonds savors the calm before the swarm. When he walked into AT&T Park on Monday, the clubhouse stereo blasted the lyrics, “Wild horses couldn’t drag me away.”

At batting practice, Bonds sat on the dugout railing, talking to teammates about pitch selection. Then he went back into the clubhouse and chatted with Mays and Willie McCovey. One-thousand-nine-hundred-twenty-three home runs sat together in one room.

The march to this milestone may be drawn out, mainly because opposing managers will not allow Bonds to keep his pace. They are already starting to treat him the way they did in 2004, walking him even when the Giants have a runner on first.

Through the first 19 games of the season, Bonds did not command such respect, drawing only two intentional walks. But in the past five games, he has been walked 10 times, seven intentionally. “If there’s an opportunity not to pitch to him, we’ll choose that avenue,” said Clint Hurdle, the Colorado Rockies’ manager.

Major League Baseball looked as if it was finished with Bonds last fall, when he was limping around on his surgically repaired right knee, hitting meager fly balls and hinting at retirement.

But as his knee has gotten stronger, Bonds’s swing has become more potent. He is now able to transfer his weight from his left leg to his right leg, allowing him to turn on pitches and drive them into McCovey Cove.

“That’s the biggest difference,” said Joe Lefebvre, the Giants’ hitting coach. “Last year, he had no strength in that front knee. He was hitting completely off his back leg.”

On Bonds’s first day of spring training, the Giants got a sense that his power had returned. Bonds walked into the batting cage and asked to face Matt Cain, the hardest-throwing pitcher on the staff.

Cain pumped two fastballs by Bonds. He threw another that Bonds fouled off. Bonds asked for one more. He smashed it about 400 feet, over the right-field fence.

“Wasn’t that awesome?” Cain said. “I really think it kick-started all this. His swing looked totally different to me from Day 1.”

The Giants, who thought seriously about letting Bonds go in the winter, must now find one more way to honor him. They are hustling to arrange another tribute — something unique yet understated, entertaining yet appropriate.

For Baer, baseball’s most experienced party planner, the home runs and the subsequent ceremonies can blend together. There was the one with the watch, the one with the car, the one with Aaron, the one that irritated the Dodgers, and the one that started after midnight.

Sitting in a conference room Tuesday, Baer unfolded a pocket schedule. For a moment, he looked like any hard-core Giants fan, trying to predict the unpredictable.

Will No. 755 come against the Red Sox? Or the Yankees? Or the Dodgers?

“You can’t over-choreograph something like this,” Baer said. “You really have to be in the moment. You have to let Barry carry the moment.”

When Bonds hit his 500th home run, in 2001, the Giants believed it was his defining accomplishment. They stopped the game. They put folding chairs on the field. They brought out a podium.

Back then, 500 seemed like the ultimate number. Now, it is 755.

But there is one more number, one more tribute, looming in the distance. It used to be inconceivable.

800.

A tribute to the life of the legendary Barry Bonds

Barry Bonds Milestone Home Runs

Sports: With Barry Bonds, Baseball should either put up or shut up

http://www.athensnews.com/issue/article.php3?story_id=28113

The one storyline that has captivated even the most casual of baseball fans is Barry Bonds' pursuit of the holy grail of sports records, Hank Aaron's home-run record. This story is interesting for a variety of reasons but the most intriguing aspect for me is just how horribly Major League Baseball has handled the entire saga. It's been the most poorly executed witch-hunt I've ever seen.

Barry Bonds is rapidly approaching hallowed baseball ground, yet so many people are trying to downplay it. His team has done little to publicize the chase, and MLB Commissioner Bud Selig still isn't even sure if he's going to be in attendance when Bonds breaks the record. Bonds had his own reality show when he was catching up to Babe Ruth's home-run mark (why can't we have "Bonds still on Bonds"?), and Hank Aaron has already declared that he's going to be on a golf course when Bonds hits number 756. It's incomprehensible that Bonds can be closing in on such an important record with such little fanfare.

Fans, many of whom are rooting vehemently for him to fail, rationalize baseball's apathetic approach by claiming that Bonds clearly used steroids and that makes him unworthy of the record. The question to ask then is if he blatantly cheated and everyone knows it, why is he still playing baseball? If it was so clear to the MLB brain trust that Bonds used steroids after they were banned in 2005, then what's taking them so long to take him down?

It's not like they haven't been trying. Bonds has been the number-one target of the War on Steroids for a long time. Sen. George Mitchell has been heading up team "Get Barry" for more than a year and has produced absolutely nothing.

The federal government is investigating Bonds for potential perjury charges. Their big trick to curtail the Bonds home-run parade? Getting a former batboy to plead guilty to distributing steroids. That's it. If this was 17th century Salem, Bonds would've been barbecued at the stake months ago whether he was innocent or not.

Apparently, there's enough evidence in the eyes of Selig and company to distance themselves from Bonds' pursuit of the game's greatest record, but there's not enough evidence to take him off the field. They can't have it both ways; either Bonds cheated and needs to be dealt with or MLB needs to do more to recognize his accomplishments when he becomes the true home-run king. If baseball can't take him down, then he must be celebrated.

At this point, it's almost easier to root for Bonds than to root against him. Anyone can jump on the anti-Bonds bandwagon and whine about how he represents everything that's wrong, and most people do because it requires little thought. Even if he's guilty as sin, though, it's still impressive that he has managed to outsmart both the federal government and MLB. Two powerful entities came after Bonds, yet it's the slugger who is still standing. And, if he's innocent, he just may be the biggest underdog in sports.

Consider all Bonds has had going against him in his pursuit of this record. First, he's had to deal with all the negative fan reaction. He's hated at every ballpark outside of San Francisco. On top of that, he's been chasing this record while dealing with the stress of being the top target of the league's investigation. He also has had to deal with the federal government investigating him for perjury. One of his biggest adversaries has been Father Time as Bonds (he'll be 43 in July) has been forced to overcome the injuries and challenges that come with age.

There isn't a current player who has faced anything close to those obstacles. At any moment, his quest for the home-run record could be derailed by a major suspension or a federal indictment, and that's if old age and nagging injuries don't end his career first. One of those factors alone could be enough to break a man, and a combination of them should be far more than enough to rattle any competitor. For now, Bonds has overcome them all. He is still standing.

And as long that continues, he needs to be treated like the future home-run king that he is.

week in week out steroid documentary

http://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=week+in+week+out+steroid+documentary&search=Search

Truth about Steroids

STEROIDS: The Truth.

Barry Bonds Home Run Watch: Hank Aaron's Asterisk

http://www.bleacherreport.com/mlb/mlb/barry-bonds-home-run-watch:-hank-aaron's-asterisk-200705041380/

As Barry Bonds creeps ever closer to Hank Aaron's career home run mark, the baseball world is going to pieces.

Fans are haunted by the prospect of steroids staining the game's most hallowed record. Commissioner Bud Selig is exploring expansion opportunities in Asia and Latin America so he'll have a good excuse to be out of the country when the big day arrives. Even the Giants brass is mulling how to low-key Number 756.

All because Barry did what many other top players were doing around the turn of the century: He used un-banned substances to improve his performance.

What has gone mostly unmentioned in the post-BALCO era is the fact that Barry hit his "tainted" homers off of JUICED PITCHERS. That's right—Major League Baseball turned a blind eye to steroids, and you can bet that many of the game's top hurlers were getting the performance edge right along with the sluggers.

In fact, you could probably make the case that performance-enhancing drugs do more to help a pitcher than a hitter, because a hitter's success depends on vision as much as strength...and I've yet to see evidence that steroids have ever improved anyone's eyes.

Which begs the question: Why are all the so-called journalists out there giving pitchers a free pass while they rush to crucify the guys in the batter's box?

Of course, there's no evidence against the pitchers of the Steroid Era—but then again baseball's absurd no-testing policy means there's little evidence against the hitters either.

My take? Yes, the hitters were juiced...and so were their nemeses on the mound. It was an even battle fought under the prevailing rules of the day.

Like they say: All's fair in drugs and war.

By acknowledging the truth as it was, we can say that Barry Bonds didn't cheat—he competed on equal terms against the pitchers of his generation. We can also say that he deserves the record he's about to break. Actually, if it's true that hurlers gained a more significant edge than hitters in Bud Selig's drugged-up game, then maybe we should think about putting an asterisk next to Hammerin' Hank's precious record:

*No home runs were hit against performance-enhanced pitchers.

PSA for Steroids

![Brotherhood" (2006) [TV-Series]](http://photos1.blogger.com/x/blogger2/1421/379621144723082/211/z/425926/gse_multipart33129.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment