http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Texas_City_Disaster

http://www.local1259iaff.org/disaster.html

http://www.americanheritage.com/articles/web/20070416-texas-city-explosion-gulf-coast-petrochemical-industry-grandcamp-monsanto.shtml

An American City Blows Up

On April 16, 1947, 60 years ago today, a burning ship carrying 2,300 tons of ammonium nitrate fertilizer exploded in the Gulf Coast port town of Texas City. Over the next day, 576 people died. It was the deadliest industrial accident in American history.

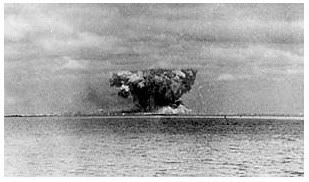

At 9:12 a.m. that day, the city of 16,000, a hub of the petrochemical industry, was rocked by the first in a series of blasts over several days, set off by a fire on the Grandcamp, a French freighter waiting for its final load of the volatile cargo. The explosion on the Grandcamp knocked two other ships, the High Flyer, packed with sulfur and another 960 tons of ammonium nitrate, and the Wilson B. Keene, loose from their moorings and sent them crashing into each other—setting the stage for another even more powerful explosion hours later. The blasts set off a deadly chain reaction that consumed a nearby Monsanto chemical plant and many other refineries in the small but dense area, as well as railroad lines and countless other structures.

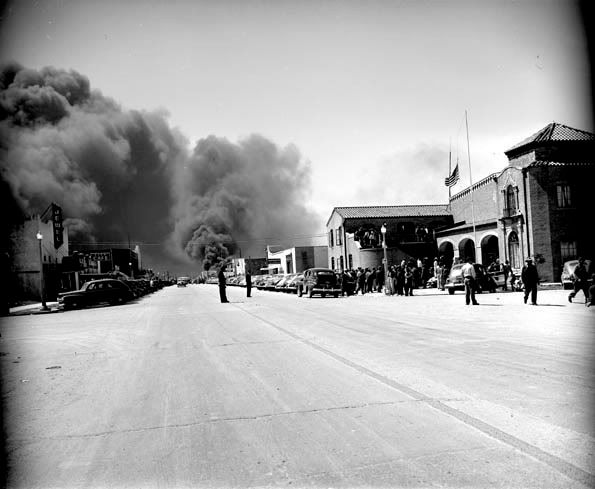

The devastation that followed is almost inconceivable outside of a movie—planes hurled from the sky, a tidal wave washing a film of acid and burning oil over the town as the injured tried to flee, huge pieces of ship and bales of burning sisal flying in every direction. It is a grisly tale of holocaust brought on first by the force of the blast and later by a miasma of burning chemicals that disintegrated clothing and consumed victims alive.

Scores of bodies were never found, including many of the 27 firefighters killed. Every morgue and hospital in the vicinity quickly filled to capacity, and in that era of segregation, many Caucasians were sent to “colored” wings of hospitals because of the film of tar and other chemicals covering their skin. The real African-American neighborhood suffered enormously; “Black Bottom” abutted the docks and was completely leveled. The mostly Mexican “El Barrio” area was similarly affected. Some suspected that the casualty rate was in fact much higher than could be documented, since many of the poorest residents were not legal citizens.

The Texas City Disaster, as it is called, isn’t well remembered today, but it was international news at the time. President Harry Truman sent the mayor of Texas City a telegram offering his deepest sympathy and promising immediate government relief. The New York Times gave the story the kind of front-page banner headline reserved for the very biggest news. Popular entertainers, Frank Sinatra and Jack Benny among them, performed at benefits for survivors. In a sense, Texas City was the Hurricane Katrina of its time, a cautionary tale about unheeded warnings and irresponsible government, with a lot unregulated industry mixed in. The tragedy also brought about the first wholesale civil action ever lodged against the United States government. Though the government was exonerated, the case paved the way for stricter regulation of the petrochemical industry and safer working conditions.

At the time, Texas City was growing rapidly. It had tripled in size since 1940, swollen with wartime and postwar jobs in the defense industry. Like much of the Texas Gulf Coast, the town was dominated by refineries and petrochemical plants—Monsanto, Humble Pipeline, Union Carbide, Amoco—and was short on housing, schools, libraries, and parks. Still, the mostly unionized workers were making decent wages, lured by “the stink of money,” as they called both their comfortable salaries and the smell of the refineries. During the war, half the population of Texas City was employed in defense-related jobs, making gasoline for military vehicles and tin and rubber for tanks and troop trucks. Now the goods were being shipped to Europe to help rebuild the devastated cities there.

Many asked how such a tragedy could happen. Others wondered why it hadn’t happened sooner. The port of Houston, about 40 miles away, was already refusing to load ammonium nitrate, which was the explosive later used in both the first attack on the World Trade Center and the Oklahoma City bombing, but Texas City had no such restrictions. According to Bill Minutaglio, author of City on Fire: The Explosion That Devastated a Texas Town and Ignited a Historical Legal Battle, “The people who ran Texas City, the people who created it, had always offered up the city. Texas City had always been a willing lubricant for the government, the military, the oil companies, and the chemical companies. . . . That was the reason it existed.”

The morning of April 16 started peacefully enough. Many remarked on the freshness of the spring day, a rarity in humid coastal Texas. As dockworkers showed up for their shifts, many lingered at the coffee shop, waiting for work to begin. A small fire had been found on the Grandcamp, and the fire department called, but no real alarm bells went off until it was too late. Curious onlookers watched without any sense of danger. The origin of the fire was never determined, and in hindsight it is difficult to say what might have hastened or hindered the explosion. The captain of the Grandcamp ordered the use of steam instead of water to quench the flames, in hopes of saving his cargo. The crew, alongside local stevedores, labored quickly while waiting for a tugboat to come from Galveston to tow the ship away from the dock, a standard practice when ships are on fire. As the fire spread and intensified, plumes of acrid crimson smoke billowed above the town, arousing much curiosity. The docks filled up with spectators, including many children, but still no one seemed to think there was anything to worry about; fires at the piers were common, and the townspeople often watched and cheered the volunteer fire department. There were even two private planes flying overhead with passengers paying to look at the scene. The first explosion incinerated both aircraft.

Sixteen hours later, as the town struggled to rescue survivors from the Grandcamp explosion and deal with the dead, a second ship, the High Flyer, blew up even more violently. It set off the Wilson B. Keene. All told, the three ships ignited a string of explosions that left at least 576 dead, 5,000 injured, 2,000 homeless, and more than 1,000 buildings flattened. Every single plate-glass window in the commercial district shattered, and there were reports of broken glass more than 20 miles away. People in Galveston, ten miles distant, were knocked to the ground, and a seismologist picked up the shock waves as far away as Denver. Most of the fire department was lost, and hundreds who had gathered to watch it put out the first fire were killed, many of them schoolchildren.

The shockwaves were felt where I grew up, too, about 100 miles from Texas City. I remember hearing stories about the tragedy as a child, mostly memories my mother had of feeling the blast from so far away, and the fear it caused. She would talk about it as we drove home from our semi-annual trips to Galveston. Both she and my father had been 10 years old at the time, going to different schools, both with family working in the refineries that blanketed the coastal inlets. Both remember car trips with their parents to look at the devastated town. Though none of my family was in Texas City when the blasts occurred, many were indirectly affected. All my grandparents had moved to southeast Texas for the same kinds of jobs as those in Texas City—work in the petrochemical plants and shipyards—and the tragedy struck a nerve. It seemed it could as easily have happened in Port Arthur or Beaumont, where they lived and worked. My grandfather and uncles, ironworkers who helped to rebuild Texas City, and men and women like them took huge risks every day, not only the immediate risk of explosions and chemical leaks, which were common, but the long-term perils of environmental poison that might eventually show up as cancer. But the hard-working residents of towns like Texas City didn’t have time to reflect on such dangers.

Today at 9 a.m. Texas City marks the sixtieth anniversary of its biggest tragedy (there have been other deadly explosions there on a lesser scale) with a ceremony honoring survivors and victims at Memorial Park. The courage and generosity of the townspeople became legendary after the disaster, and even today nearly every one in the town has a personal connection to the event. Nearby are the graves of 63 unidentified victims, as well as the anchor from the Grandcamp and a giant propeller from the High Flyer. There are also plaques with names of the dead, including the 27 firemen, sculptures, and an “Angel of Peace” fountain. Texas City is a placid town of 42,000 today, still an important port for the petrochemical industry. After today’s ceremony the town will go back to work, not forgetting but also not dwelling on the past.

—Amy Weaver Dorning is a freelance writer in San Francisco.

http://www.myfoxhouston.com/myfox/pages/News/Detail?contentId=2933408&version=2&locale=EN-US&layoutCode=TSTY&pageId=3.2.1

Texas City to Mark 60th Anniversary of Deadly Blast

TEXAS CITY, Texas -- Jo Ann Stansfield was only 17 years old when her city was faced with one of its darkest hours.

Sixty years ago Monday, a French ship carrying 2,300 tons of fertilizer exploded in Galveston Bay. The explosion caused two subsequent explosions that destroyed dozens of homes, businesses and buildings.

Stansfield was at her high school in study hall when she knew something was wrong.

"You started to run to windows to see what it was, but the windows broke, so you ran the other way to the hall," Stansfield said.

Stansfield's mother was injured during the explosions but she and her family survived. However, 600 other people did not and thousands of others were injured.

Sixth Street was one of the hardest-hit areas. It took years to rebuild and is now commonly referred to as the "street of memories." Stansfiled said just about everyone she knew had a family member who died or was injured from the explosion.

"You can't believe it's real. I mean, how could that be happening, when you see bodies on the curb of 6th Street piled up like hoards of wood," Stansfield said.

Stansfield said he high school graduation ceremony went on as planned months later but it just wasn't the same.

"To see so many of my classmates up there that went through with a member of their family lost, you had to feel for them," Stansfield said.

Texas City will commemorate the 60th anniversary of the disaster on Monday, April 16 at 9 a.m. at The Memorial Park, located in the 2900 block of Loop 197.

![Brotherhood" (2006) [TV-Series]](http://photos1.blogger.com/x/blogger2/1421/379621144723082/211/z/425926/gse_multipart33129.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment