Oklahoma City Bombing

Add to My Profile | More Videos

Oklahoma City bombing

http://www.courttv.com/archive/casefiles/oklahoma/

Online NewsHour -- The Oklahoma City Bombing

http://video.yahoo.com/video/play?vid=1075737805

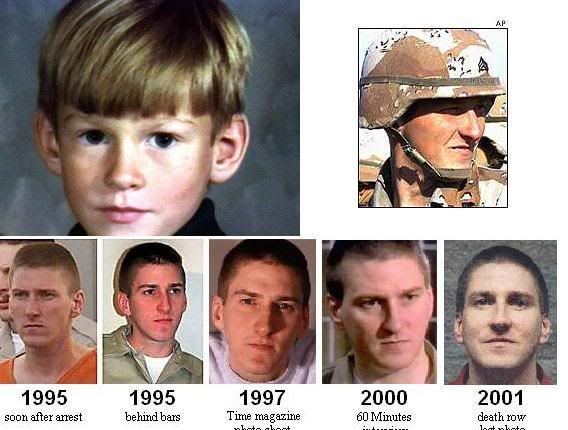

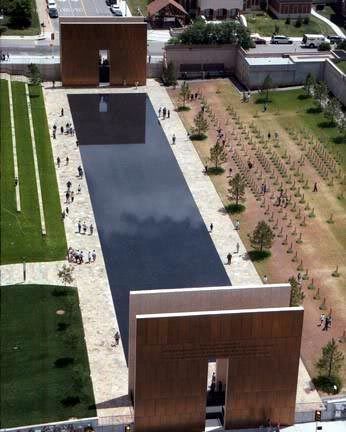

Oklahoma City Bombing (19 April 1995), a devastating act of domestic terrorism, in which political extremist Timothy McVeigh bombed the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. McVeigh's truck bomb, made of fertilizer and diesel fuel, killed 168 people, including 19 children, and injured more than 500 others. Television coverage burned the catastrophe into the nation's psyche with chilling images of bodies being removed from the rubble. The mass murderer turned out to be a 27-year-old decorated U.S. Army veteran of the Persian Gulf War with extreme antigovernment views. McVeigh's motive was to avenge a bloody 19 April 1993 federal raid on the Branch Davidian sect in Waco, Tex., in which some 80 people died. The Federal Bureau of Investigation tracked McVeigh down through the Ryder rental truck that exploded in Oklahoma City. An accomplice, Terry Nichols, was implicated through a receipt for fertilizer and a getaway map linked to the blast. The FBI also searched unsuccessfully for an unidentified "John Doe" suspect whom eyewitnesses placed at the crime scene. This phantom suspect, and the trials of McVeigh and Nichols—both of whom pleaded not guilty—fueled theories of a larger conspiracy. But prosecutors maintained the men acted alone, and both were convicted. McVeigh was sentenced to death, and eventually admitted he carried out the strike. Nichols was sentenced to life in prison for his role. Just five days before McVeigh was scheduled to die, his case took a final dramatic turn. The FBI admitted it had withheld 3,135 documents from McVeigh's lawyers. The execution was briefly postponed. But on 11 June 2001, in Terre Haute, Ind., McVeigh was put to death by lethal injection. Through a grant of special permission by the U.S. Attorney General, victims and survivors watched the execution on closed-circuit television in Oklahoma City.

http://www.answers.com/topic/oklahoma-city-bombing

Oklahoma City bombing

http://www.courttv.com/archive/casefiles/oklahoma/

Online NewsHour -- The Oklahoma City Bombing

http://video.yahoo.com/video/play?vid=1075737805

Survivors mark 12th anniversary of Oklahoma City bombing

April 19, 2007 06:17 EDT

OKLAHOMA CITY (AP) -- It was 12 years ago today that 168 people were killed in the bomb attack on the Oklahoma City federal building, ushering America into the modern age of terrorism.

The bomb was a rental truck loaded with more than two tons of ammonium nitrate and fuel oil. Timothy McVeigh, the war veteran who drove it there, was later convicted of murder and executed. Federal prosecutors say the attack was a twisted attempt to avenge the deaths of dozens two years earlier in the federal operation that ended a cult standoff in Waco, Texas.

Today, survivors of the Oklahoma bombing and families of those killed gather again at the site to remember. There will be 168 seconds of silence followed by a reading of the names of the victims.

There'll be remarks by former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani, who guided his city through the horrors of Nine-Eleven.

This year's Oklahoma observance will also honor the 32 people murdered this week by a suicide-killer at Virginia Tech.

CNN) -- Timothy McVeigh was born April 23, 1968 in Pendleton, New York, and grew up in that rural commuity near Buffalo, Niagara and Canada. He was the middle of three children, and the only boy.

His father worked at a nearby General Motors manufacturing plant; his mother worked for a travel agency. His parents separated for a third and final time in 1984.

High school classmates remember him as small, thin and quiet. He became involved in school functions -- football, track, extra-curricular activities -- but after joining them, soon dropped out. He was shy, did not have a girlfriend and did not date. He did not belong to any clique, but seemed to exist on the margins.

McVeigh graduated from high school in June, 1986 and in the fall, entered a two-year business college. He attended only a short time. During that time McVeigh lived at home with his father, worked at a Burger King and drove dilapidated, old cars.

In 1987 he got a pistol permit from Niagara County and a job in Buffalo as a guard on an armored car. A co-worker recalls that McVeigh owned numerous firearms and had a survivalist philosophy -- a tendency to stockpile weapons and food in preparation for what he believed to be the imminent breakdown of society. In 1988 McVeigh and a friend bought 10 acres of rural land and used it as a shooting range.

McVeigh enlisted in the Army in Buffalo in May 1988, and went through basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia. After basic training, his unit was transferred to Fort Riley, Kansas, and became part of the Army's 1st Infantry Division.

McVeigh became a gunner on a Bradley Fighting Vehicle. He was promoted to corporal, sergeant, then platoon leader. Fellow soldiers recalled that McVeigh was very interested in military stuff, kept his own personal collection of firearms and constantly cleaned and maintained them. Other soldiers went into town to look for entertainment or companionship but McVeigh stayed on base and cleaned his guns. During his time in the Army, he also read and recommended to others "The Turner Diaries,"-- a racist, anti-Semitic novel about a soldier in an underground army. A former roommate said that McVeigh would panic at the prospect of the government taking away peoples' guns, but that he was not a racist and was basically indifferent to racial matters.

While at Fort Riley, McVeigh reenlisted in the Army. He aspired to be a member of the Special Forces and in 1990 was accepted into a 3-week school to assess his potential for joining that elite unit. He had barely begun to prepare himself physically for Special Forces training when, in January 1991, the 1st Infantry Division was sent to participate in the Persian Gulf War. As a gunnery sergeant, McVeigh was in action during late February, 1991. Pursuing his desire of joining the Special Forces, he left the Persian Gulf theater early and went to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, where he took a battery of IQ, personality and aptitude tests to qualify for Special Forces. However, his participation in the Persian Gulf War had left him no time to prepare himself physically for the demands of Special Forces training. McVeigh was unable to endure a 90-minute march with a 45-pound pack, and he withdrew from the program after two days.

This disappointing experience left him facing years of active service due to his reenlistment at Fort Riley. The Army was downsizing however, and after 3 1/2 years of service, McVeigh took the offer of an early discharge and got out of the military in the fall of 1991.

By January 1992, at age 24, McVeigh was back where he had started, living with his father in Pendleton, New York, driving an old car and working as a security guard.

In January 1993 McVeigh left Pendleton, and began to travel, moving himself and his belongings about in a series of battered old cars. He lived in cheap motels and trailer parks, but also stayed with two Army buddies, Michael Fortier in Kingman, Arizona, and Terry Nichols in Decker, Michigan.

McVeigh traveled to Waco, Texas during the March-April 1993 standoff between the Branch Davidians and federal agents, and was said to have been angry about what he saw. He sold firearms at a gun show in Arizona and was heard to remark on one weapon's ability to shoot down an ATF helicopter.

Although both Arizona and Michigan are host to militant anti-tax, anti-government, survivalist and racist groups, there is no evidence that he ever belonged to any extremist groups. He advertised to sell a weapon in what is described as a virulently anti-Semitic publication. After renting a Ryder truck that has been linked to the Oklahoma City bombing, McVeigh telephoned a religious community that preaches white supremacy, but no one there can remember knowing him or talking to him. His only known affiliations are as a registered Republican in his New York days, and as a member of the National Rifle Association while he was in the Army.

Terry Lynn Nichols, of Herington, Kan. Convicted on charges on conspiracy and involuntary manslaughter; could be sentenced to life in prison at sentencing on June 4, 1998. Served in Army with co-defendant Timothy McVeigh at Fort Riley, Kan.; left in 1989 on unspecified hardship discharge. Renounced right to vote in 1992. Lived with second wife and their 2-year-old daughter; has teen-age son by first marriage. Surrendered to police April 21, 1995; initially held as a witness.

Michael Fortier

Though Michael Fortier was considered an accomplice and co-conspirator, he agreed to testify against McVeigh in exchange for a modest sentence and immunity for his wife. He was sentenced on May 27, 1998 to 12 years in prison and fined $200,000 for failing to warn authorities about the attack. As discussed by Jeralyn Merritt, who served on Timothy McVeigh's criminal defense team, on January 20, 2006, after serving eighty-five percent of his sentence, Fortier was released for good behavior into the Witness Protection Program and given a new identity.

No "John Doe #2" was ever identified, nothing conclusive was ever reported regarding the owner of the missing leg, and the government never openly investigated anyone else in conjunction with the bombing. Though the defense teams in both McVeigh's and Nichols trials tried to suggest that others were involved, Judge Steven W. Taylor, who presided over the Nichols trial, found no credible, relevant, or legally admissible evidence of anyone other than McVeigh and Nichols as having directly participated in the bombing.

The Survivor Tree

John Doe No. 2 remains focus of conspiracy theory 12 years after Oklahoma City bombing

http://www.cushingdaily.com/local/local_story_108103632.html

OKLAHOMA CITY (AP) - He was the focus of one of the largest manhunts in U.S. history, a dark-haired, muscular man known only as John Doe No. 2.

Some witnesses claim they saw him with Timothy McVeigh in the days leading up to the deadly Oklahoma City bombing, but he was never found and investigators say he probably never existed.

But 12 years after the April 19, 1995, bombing that killed 168 people, Salt Lake City attorney Jesse Trentadue says he knows the identity of this mystery man and that his brother's death may be tied to his resemblance to a suspect who died in 1996.

Horrific events like the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building can inspire talk of conspiracies for years.

But Trentadue's theory is full of intrigue. He claims it points to a wide conspiracy, a conspiracy the government says did not exist.

He has collected volumes of information from the government and other sources as he investigates the death of his brother, Kenneth Michael Trentadue, at a federal prison in Oklahoma City just four months after the Oklahoma City bombing.

Trentadue believes his brother was murdered in a case of mistaken identity with a member of a white supremacist bank robbery gang with ties to McVeigh.

It was this man, Richard Lee Guthrie Jr., who formed the basis for the sketch of John Doe No. 2. According to the theory, Trentadue's brother looked much like Guthrie. They both had a dragon tattoo on the left arm. They both were about the same height, build and had the same dark eyes.

Each was found hanging in a jail cell _ Trentadue on Aug. 21, 1995, and Guthrie in July 1996 in Kentucky after he was convicted of bank robbery charges.

FBI documents and other evidence point to a relationship between McVeigh, the bank robbery gang and Elohim City, a white separatist community in eastern Oklahoma.

Members of the gang, known as the Midwestern Bank Bandits, robbed 22 banks in the mid 1990s and were frequent visitors to the Elohim City compound. They used profits from their robberies to support white-supremacist causes.

"They robbed banks with McVeigh," Trentadue said.

McVeigh also had contact with the compound. McVeigh telephoned Elohim City in the days leading up to the bombing in what authorities said was an attempt to recruit help to carry out the bomb plot. Guthrie was a member of that gang, Trentadue said.

"I'm convinced now that Guthrie was John Doe No. 2. Guthrie was a perfect match," Trentadue said.

Descriptions of John Doe No. 2, were provided by employees at a Junction City, Kan., body shop who said he accompanied McVeigh when he rented the Ryder rental truck that was used to carry the deadly bomb.

Weeks after the bombing, federal investigators concluded witnesses had mistakenly identified an army private from Fort Riley, Kan., as McVeigh's accomplice and that John Doe No. 2 did not exist. The soldier, who wore a Carolina Panthers baseball cap and vaguely resembled the composite drawing, came into the shop the following day to rent a truck.

Kenneth Trentadue, who was convicted of a 1982 bank robbery, was detained at the Mexican border in June 1995 on suspicion of drunken driving and picked up by federal authorites on a warrant for an outstanding parole violation.

He was transferred to Oklahoma City on Aug. 18, 1995. Three days later, he was found hanging from a braided bed sheet in a supposedly suicide-proof isolation cell.

Trentadue's body was bloody and bruised, and the medical examiner initially said he was "very likely" murdered. His neck had a ligature mark apparently made by plastic handcuffs and his knuckles were black with bruises.

"There was a hell of a fight," Jesse Trentadue said. But following a lengthy investigation, authorities ruled the death a suicide.

Trentadue said he believes his brother died during a violent interrogation by federal authorities who mistook him for Guthrie and were questioning him about his knowledge of the bomb plot.

"And, of course, he wouldn't know anything about it," he said. "I don't think they intended to kill him. I think it got out of hand."

A November 1999 report by the Department of Justice's Office of Inspector General states that, shortly after arriving at the Federal Transfer Center, Trentadue asked to be placed in protective custody and said he had a feeling "things aren't quite right."

"He said that his problems might have resulted from a case of mistaken identity," the report states.

"It is incredible, sickening if it is true," said Trentadue, who is in a protracted and bitter court fight with the government over his brother's death.

"I didn't start out going down this road. I was led down this road by the evidence," Jesse Trentadue said. "I think I have proven who committed the bombing. I don't think I will ever prove who killed my brother."

A spokesman for the FBI in Washington, Paul Bresson, said the agency believes everyone responsible for the bombing has been prosecuted.

"While conspiracy theories continue to circulate twelve years later, no evidence that others were involved in the bombing was corroborated by the investigation," Bresson said. "Furthermore, such unfounded claims only serve to add to the pain and suffering of victim families who have lived this tragedy now for more than a decade."

Suggestions that others were involved have played a key role in the defense strategies at criminal bombing trials, most recently bombing coconspirator Terry Nichols' trial on Oklahoma murder charges in 2004.

Nichols' defense attorney, Brian Hermanson of Ponca City, said the FBI aggressively searched for the John Doe No. 2 suspect until a few weeks after the bombing, when they announced they had rounded up all the suspects.

He said McVeigh's 2001 execution for federal murder convictions means lingering questions about the suspect's relationship with the bomb plot may never be answered.

"I wish they wouldn't have killed McVeigh so we could ask him those questions," Hermanson said. "That's the problem with killing people _ you lose your source."

Nichols is serving life prison sentences on federal and state bombing charges. A third person, Michael Fortier, pleaded guilty to not telling authorities in advance about the bomb plot and was released from a federal prison last year after serving about 85 percent of a 12-year sentence.

![Brotherhood" (2006) [TV-Series]](http://photos1.blogger.com/x/blogger2/1421/379621144723082/211/z/425926/gse_multipart33129.jpg)

1 comment:

Here is an interesting BBC Show about the Oklahoma City Bombing. Please watch and then pass link along to friends.

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=5977554184697409940

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=5977554184697409940

Post a Comment