Researchers: Human evolution speeding up

http://www.usatoday.com/tech/science/discoveries/2007-12-10-evolution-speeding-up_N.htm

By tracking the footprints of evolution along the human genome, a team of researchers on Monday reported for the first time that the pace of evolution is quickening with the passing generations.

The findings represent the latest in a series of landmark efforts to use the human genome, which was decoded in 2003, to understand human biology and unravel the mysteries of evolution.

The findings support the notion that the planet's exploding population is a living laboratory for genetic trial and error, researchers say. By tracking the changes over time, the researchers found clear evidence that we're not who we used to be.

Many of these changes were forced on early humans by changing conditions, including waves of infectious diseases, the shift to an agricultural diet and migrations to colder climates. Some are still unexplained.

For instance, just 10,000 years ago — the blink of an eye in evolutionary time — fewer people carried the gene for an enzyme called lactase, which allows humans to digest cow's milk. A bigger proportion of people had the dark skin of our African ancestors, and no one had blue eyes.

"Blue eyes are new," says lead author John Hawks of the University of Wisconsin.

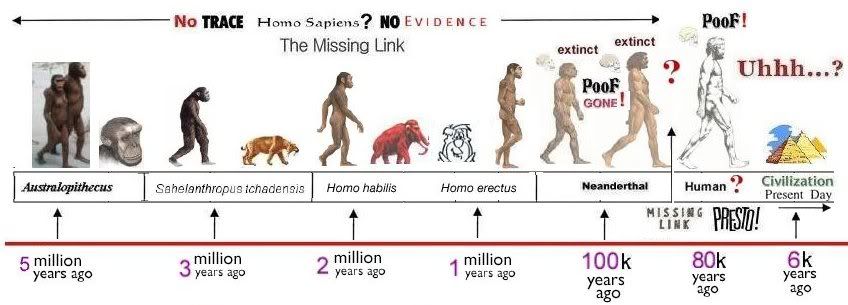

Hawks says the findings, in today's Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, are merely "breaking the ice" in a rapidly expanding effort to use genetics to explain how people have changed since the first humanlike creatures appeared 7 million years ago.

"It's a very important paper," says Clark Larsen, chairman of anthropology at Ohio State University. He says his own study of physical evidence supports the researchers' notion that there was "a ton" of biological change in the past 10,000 years. "Ten thousand years is a tiny part of the picture of human evolution," he says. "It's still going on. Right before our eyes."

Some evolving traits are simple to track. Blue eyes today are common, and millions of people in northern climates now carry the lactase gene, along with about half of those living along the Mediterranean. Why did the lactase gene spread so rapidly? Because it helps people survive and bear children, says co-author Henry Harpending of the University of Utah.

"If you can metabolize milk sugar rapidly, it gives you an advantage when food is scarce," he says.

People who survive are more likely to pass a gene along to their offspring, who also are better able to survive and reproduce. But inheriting a gene doesn't always confer an advantage, Harpending says.

The gene for sickle cell anemia offers an advantage to people living in equatorial Africa, because it helps guard against malaria.

Outside Africa, it's a different story. If a child inherits two copies, one from each parent, the blessing can become a deadly scourge. "In the U.S., where there's no malaria, there are at least 70,000 people leading impaired lives," Harpending says.

Other genetic changes have taken root in the genome, though they don't have any obvious influence on survival or reproduction. "What do people with blue eyes have that made them have more children?" Hawks asks. "I dunno."

Researchers: Human evolution speeding up

http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20071211/ap_on_sc/evolution_speedup;_ylt=AgUWCrYsvx9bRxUspXQwUzas0NUE

Science fiction writers have suggested a future Earth populated by a blend of all races into a common human form. In real life, the reverse seems to be happening. People are evolving more rapidly than in the distant past, with residents of various continents becoming increasingly different from one another, researchers say.

"I was raised with the belief that modern humans showed up 40,000 to 50,000 years ago and haven't changed," explained Henry C. Harpending, an anthropologist at the University of Utah. "The opposite seems to be true."

"Our species is not static," Harpending added in a telephone interview.

That doesn't mean we should expect major changes in a few generations, though, evolution occurs over thousands of years.

Harpending and colleagues looked at the DNA of humans and that of chimpanzees, our closest relatives, they report in this week's online edition of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

If evolution had been proceeding steadily at the current rate since humans and chimps separated 6 million years ago there should be 160 times more differences than the researchers found.

That indicates that human evolution had been slower in the distant past, Harpending explained.

"Rapid population growth has been coupled with vast changes in cultures and ecology, creating new opportunities for adaptation," the study says. "The past 10,000 years have seen rapid skeletal and dental evolution in human populations, as well as the appearance of many new genetic responses to diet and disease."

And they found that different changes are occurring in Africans, Asians and Europeans.

Most anthropologists agree that humans first evolved in Africa and then spread to other areas, and the lighter skin color of Europeans and Asians is generally attributed to selection to allow more absorption of vitamin D in colder climate where there is less sun.

The increase in human population from millions to billions in the last 10,000 years accelerated the rate of evolution because "we were in new environments to which we needed to adapt," Harpending adds. "And with a larger population, more mutations occurred."

In another example, the researchers noted that in China and most of Africa, few people can digest fresh milk into adulthood. Yet in Sweden and Denmark, the gene that makes the milk-digesting enzyme lactase remains active, so almost everyone can drink fresh milk, explaining why dairy farming is more common in Europe than in the Mediterranean and Africa, Harpending says.

The researchers studied 3.9 million gene snippets from 270 people in four populations: Han Chinese, Japanese, Africa's Yoruba tribe and Utah Mormons who traced their ancestry to northern Europe.

Richard Potts, director of the human origins program at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History, said he thinks the researchers reasoning regarding rapid adaptive change is plausible.

The study mainly points to an overall expansion in the human population over the past 40,000 years to explain the genetic data.

"Yet the archaeological record also shows that humans increasingly divided themselves into distinct cultures and migrating groups — factors that seem to play only a small role in their analysis. Dividing the human population into finer units and their movement into new regions — the Arctic, Oceania, tropical forests, just to name some — may have also forced quicker adaptive evolution in our species," Potts said.

Potts, who was not part of the research team, added that he liked the report "because it points to how genetic data can be used to test a variety of ideas about recent human adaptation."

Two years ago Harpending and colleague Gregory M. Cochran published a study arguing that above-average intelligence in Ashkenazi Jews — those of northern European heritage — resulted from natural selection in medieval Europe, where they were pressured into jobs as financiers, traders, managers and tax collectors.

Those who were smarter succeeded, grew wealthy and had bigger families to pass on their genes, they suggested. That evolution also is linked to genetic diseases such as Tay-Sachs and Gaucher in Jews.

The new study was funded by the Department of Energy, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of Aging, the Unz Foundation, the University of Utah and the University of Wisconsin.

Human evolution at the crossroads

Genetics, cybernetics complicate forecast for species

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/7103668/

Scientists are fond of running the evolutionary clock backward, using DNA analysis and the fossil record to figure out when our ancestors stood erect and split off from the rest of the primate evolutionary tree.

But the clock is running forward as well. So where are humans headed?

Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins says it's the question he's most often asked, and "a question that any prudent evolutionist will evade." But the question is being raised even more frequently as researchers study our past and contemplate our future.

Paleontologists say that anatomically modern humans may have at one time shared the Earth with as many as three other closely related types — Neanderthals, Homo erectus and the dwarf hominids whose remains were discovered last year in Indonesia.

Does evolutionary theory allow for circumstances in which "spin-off" human species could develop again?

Some think the rapid rise of genetic modification could be just such a circumstance. Others believe we could blend ourselves with machines in unprecedented ways — turning natural-born humans into an endangered species.

Present-day fact, not science fiction

Such ideas may sound like little more than science-fiction plot lines. But trend-watchers point out that we're already wrestling with real-world aspects of future human development, ranging from stem-cell research to the implantation of biocompatible computer chips. The debates are likely to become increasingly divisive once all the scientific implications sink in.

"These issues touch upon religion, upon politics, upon values," said Gregory Stock, director of the Program on Medicine, Technology and Society at the University of California at Los Angeles. "This is about our vision of the future, essentially, and we'll never completely agree about those things."

The problem is, scientists can't predict with precision how our species will adapt to changes over the next millennium, let alone the next million years. That's why Dawkins believes it's imprudent to make a prediction in the first place.

Others see it differently: In the book "Future Evolution," University of Washington paleontologist Peter Ward argues that we are making ourselves virtually extinction-proof by bending Earth's flora and fauna to our will. And assuming that the human species will be hanging around for at least another 500 million years, Ward and others believe there are a few most likely scenarios for the future, based on a reading of past evolutionary episodes and current trends.

Where are humans headed? Here's an imprudent assessment of five possible paths, ranging from homogenized humans to alien-looking hybrids bred for interstellar travel.

Unihumans: Will we all be assimilated?

Biologists say that different populations of a species have to be isolated from each other in order for those populations to diverge into separate species. That's the process that gave rise to 13 different species of "Darwin's Finches" in the Galapagos Islands. But what if the human species is so widespread there's no longer any opening for divergence?

Evolution is still at work. But instead of diverging, our gene pool has been converging for tens of thousands of years — and Stuart Pimm, an expert on biodiversity at Duke University, says that trend may well be accelerating.

"The big thing that people overlook when speculating about human evolution is that the raw matter for evolution is variation," he said. "We are going to lose that variability very quickly, and the reason is not quite a genetic argument, but it's close. At the moment we humans speak something on the order of 6,500 languages. If we look at the number of languages we will likely pass on to our children, that number is 600."

Cultural diversity, as measured by linguistic diversity, is fading as human society becomes more interconnected globally, Pimm argued. "I do think that we are going to become much more homogeneous," he said.

Ken Miller, an evolutionary biologist at Brown University, agreed: "We have become a kind of animal monoculture."

Is that such a bad thing? A global culture of Unihumans could seem heavenly if we figure out how to achieve long-term political and economic stability and curb population growth. That may require the development of a more "domesticated" society — one in which our rough genetic edges are smoothed out.

But like other monocultures, our species could be more susceptible to quick-spreading diseases, as last year's bird flu epidemic illustrated.

"The genetic variability that we have protects us against suffering from massive harm when some bug comes along," Pimm said. "This idea of breeding the super-race, like breeding the super-race of corn or rice or whatever — the long-term consequences of that could be quite scary."

Environmental pressures wouldn't stop

Even a Unihuman culture would have to cope with evolutionary pressures from the environment, the University of Washington's Peter Ward said.

Some environmentalists say toxins that work like estrogens are already having an effect: Such agents, found in pesticides and industrial PCBs, have been linked to earlier puberty for women, increased incidence of breast cancer and lower sperm counts for men.

"One of the great frontiers is going to be trying to keep humans alive in a much more toxic world," he observed from his Seattle office. "The whales of Puget Sound are the most toxic whales on Earth. Puget Sound is just a huge cesspool. Well, imagine if that goes global."

Global epidemics or dramatic environmental changes represent just two of the scenarios that could cause a Unihuman society to crack, putting natural selection — or perhaps not-so-natural selection — back into the evolutionary game. Then what?

Survivalistians: Coping with doomsday

Surviving doomsday is a story as old as Noah’s Ark, and as new as the post-bioapocalypse movie “28 Days Later.”

Catastrophes ranging from super-floods to plagues to nuclear war to asteroid strikes erase civilization as we know it, leaving remnants of humanity who go their own evolutionary ways.

The classic Darwinian version of the story may well be H.G. Wells’ “The Time Machine,” in which humanity splits off into two species: the ruthless, underground Morlock and the effete, surface-dwelling Eloi.

At least for modern-day humans, the forces that lead to species spin-offs have been largely held in abeyance: Populations are increasingly in contact with each other, leading to greater gene-mixing. Humans are no longer threatened by predators their own size, and medicine cancels out inherited infirmities ranging from hemophilia to nearsightedness.

“We are helping genes that would have dropped out of the gene pool,” paleontologist Peter Ward observed.

But in Wells’ tale and other science-fiction stories, a civilization-shattering catastrophe serves to divide humanity into separate populations, vulnerable once again to selection pressures. For example, people who had more genetic resistance to viral disease would be more likely to pass on that advantage to their descendants.

If different populations develop in isolation over many thousands of generations, it’s conceivable that separate species would emerge. For example, that virus-resistant strain of post-humans might eventually thrive in the wake of a global bioterror crisis, while less hardy humans would find themselves quarantined in the world’s safe havens.

Patterns in the spread of the virus that causes AIDS may hint at earlier, less catastrophic episodes of natural selection, said Stuart Pimm, a conservation biologist at Duke University: “There are pockets of people who don’t seem to become HIV-positive, even though they have a lot of exposure to the virus — and that may be because their ancestors survived the plague 500 years ago.”

Evolution, or devolution?

If the catastrophe ever came, could humanity recover? In science fiction, that’s an intriguingly open question. For example, Stephen Baxter’s novel “Evolution” foresees an environmental-military meltdown so severe that, over the course of 30 million years, humans devolve into separate species of eyeless mole-men, neo-apes and elephant-people herded by their super-rodent masters.

Even Ward gives himself a little speculative leeway in his book “Future Evolution,” where a time-traveling human meets his doom 10 million years from now at the hands — or in this case, the talons — of a flock of intelligent killer crows. But Ward finds it hard to believe that even a global catastrophe would keep human populations isolated long enough for our species to split apart.

“Unless we totally forget how to build a boat, we can quickly come back,” Ward said.

Even in the event of a post-human split-off, evolutionary theory dictates that one species would eventually subjugate, assimilate or eliminate their competitors for the top job in the global ecosystem. Just ask the Neanderthals.

“If you have two species competing over the same ecological niche, it ends badly for one of them, historically,” said Joel Garreau, the author of the forthcoming book “Radical Evolution.”

The only reason chimpanzees still exist today is that they “had the brains to stay up in the trees and not come down into the open grasslands,” he noted.

“You have this optimistic view that you’re not going to see speciation (among humans), and I desperately hope that’s right,” Garreau said. “But that’s not the only scenario.”

Numans: Rise of the superhumans

We’ve already seen the future of enhanced humans, and his name is Barry Bonds.

The controversy surrounding the San Francisco Giants slugger, and whether steroids played a role in the bulked-up look that he and other baseball players have taken on, is only a foretaste of what’s coming as scientists find new genetic and pharmacological ways to improve performance.

Developments in the field are coming so quickly that social commentator Joel Garreau argues that they represent a new form of evolution. This radical kind of evolution moves much more quickly than biological evolution, which can take millions of years, or even cultural evolution, which works on a scale of hundreds or thousands of years.

How long before this new wave of evolution spawns a new kind of human? “Try 20 years,” Garreau told MSNBC.com.

In his latest book, “Radical Evolution,” Garreau reels off a litany of high-tech enhancements, ranging from steroid Supermen, to camera-equipped flying drones, to pills that keep soldiers going without sleep or food for days.

“If you look at the superheroes of the ’30s and the ’40s, just about all of the technologies they had exist today,” he said.

Three kinds of humans

Such enhancements are appearing first on the athletic field and the battlefield, Garreau said, but eventually they’ll make their way to the collegiate scene, the office scene and even the dating scene.

“You’re talking about three different kinds of humans: the enhanced, the naturals and the rest,” Garreau said. “The enhanced are defined as those who have the money and enthusiasm to make themselves live longer, be smarter, look sexier. That’s what you’re competing against.”

In Garreau’s view of the world, the naturals will be those who eschew enhancements for higher reasons, just as vegetarians forgo meat and fundamentalists forgo what they see as illicit pleasures. Then there’s all the rest of us, who don’t get enhanced only because they can’t. “They loathe and despise the people who do, and they also envy them,” Garreau said.

Scientists acknowledge that some of the medical enhancements on the horizon could engender a “have vs. have not” attitude.

“But I could be a smart ass and ask how that’s different from what we have now,” said Brown University’s Ken Miller.

Medical advances as equalizers

Miller went on to point out that in the past, “advances in medical science have actually been great levelers of social equality.” For example, age-old scourges such as smallpox and polio have been eradicated, thanks to public health efforts in poorer as well as richer countries. That trend is likely to continue as scientists learn more about the genetic roots of disease, he said.

“In terms of making genetic modifications to ourselves, it’s much more likely we’ll start to tinker with genes for disease susceptibility. … Maybe there would be a long-term health project to breed HIV-resistant people,” he said.

When it comes to discussing ways to enhance humans, rather than simply make up for disabilities, the traits targeted most often are longevity and memory. Scientists have already found ways to enhance those traits in mice.

Imagine improvements that could keep you in peak working condition past the age of 100. Those are the sorts of enhancements you might want to pass on to your descendants — and that could set the stage for reproductive isolation and an eventual species split-off.

“In that scenario, why would you want your kid to marry somebody who would not pass on the genes that allowed your grandchildren to have longevity, too?” the University of Washington’s Peter Ward asked.

But that would require crossing yet another technological and ethical frontier.

Instant superhumans — or monsters?

To date, genetic medicine has focused on therapies that work on only one person at a time. The effects of those therapies aren’t carried on to future generations. For example, if you take muscle-enhancing drugs, or even undergo gene therapy for bigger muscles, that doesn’t mean your children will have similarly big muscles.

In order to make an enhancement inheritable, you’d have to have new code spliced into your germline stem cells — creating an ethical controversy of transcendent proportions.

Tinkering with the germline could conceivably produce a superhuman species in a single generation — but could also conceivably create a race of monsters. “It is totally unpredictable,” Ward said. “It’s a lot easier to understand evolutionary happenstance.”

Even then, there are genetic traits that are far more difficult to produce than big muscles or even super-longevity — for instance, the very trait that defines us as humans.

“It’s very, very clear that intelligence is a pretty subtle thing, and it’s clear that we don’t have a single gene that turns it on or off,” Miller said.

When it comes to intelligence, some scientists say, the most likely route to our future enhancement — and perhaps our future competition as well — just might come from our own machines.

Cyborgs: Merging with the machines

Will intelligent machines be assimilated, or will humans be eliminated?

Until a few years ago, that question was addressed only in science-fiction plot lines, but today the rapid pace of cybernetic change has led some experts to worry that artificial intelligence may outpace Homo sapiens’ natural smarts.

The pace of change is often stated in terms of Moore’s Law, which says that the number of transistors packed into a square inch should double every 18 months. “Moore’s Law is now on its 30th doubling. We have never seen that sort of exponential increase before in human history,” said Joel Garreau, author of the book “Radical Evolution.”

In some fields, artificial intelligence has already bested humans — with Deep Blue’s 1997 victory over world chess champion Garry Kasparov providing a vivid example.

Three years later, computer scientist Bill Joy argued in an influential Wired magazine essay that we would soon face challenges from intelligent machines as well as from other technologies ranging from weapons of mass destruction to self-replicating nanoscale “gray goo.”

Joy speculated that a truly intelligent robot may arise by the year 2030. “And once an intelligent robot exists, it is only a small step to a robot species — to an intelligent robot that can make evolved copies of itself,” he wrote.

Assimilating the robots

To others, it seems more likely that we could become part-robot ourselves: We’re already making machines that can be assimilated — including prosthetic limbs, mechanical hearts, cochlear implants and artificial retinas. Why couldn’t brain augmentation be added to the list?

“The usual suggestions are that we’ll design improvements to ourselves,” said Seth Shostak, senior astronomer at the SETI Institute. “We’ll put additional chips in our head, and we won’t get lost, and we’ll be able to do all those math problems that used to befuddle us.”

Shostak, who writes about the possibilities for cybernetic intelligence in his book “Sharing the Universe,” thinks that’s likely to be a transitional step at best.

“My usual response is that, well, you can improve horses by putting four-cylinder engines in them. But eventually you can do without the horse part,” he said. “These hybrids just don’t strike me as having a tremendous advantage. It just means the machines aren’t good enough.”

Back to biology

University of Washington paleontologist Peter Ward also believes human-machine hybrids aren’t a long-term option, but for different reasons.

“When you talk to people in the know, they think cybernetics will become biology,” he said. “So you’re right back to biology, and the easiest way to make changes is by manipulating genomes.”

It’s hard to imagine that robots would ever be given enough free rein to challenge human dominance, but even if they did break free, Shostak has no fear of a “Terminator”-style battle for the planet.

“I’ve got a couple of goldfish, and I don’t wake up in the morning and say, ‘I’m gonna kill these guys.’ … I just leave ’em alone,” Shostak said. “I suspect the machines would very quickly get to a level where we were kind of irrelevant, so I don’t fear them. But it does mean that we’re no longer No. 1 on the planet, and we’ve never had that happen before.”

Astrans: Turning into an alien race

If humans survive long enough, there’s one sure way to grow new branches on our evolutionary family tree: by spreading out to other planets.

Habitable worlds beyond Earth could be a 23rd century analog to the Galapagos Islands, Charles Darwin’s evolutionary laboratory: just barely close enough for travelers to get to, but far enough away that there'd be little gene-mixing with the parent species.

“If we get off to the stars, then yes, we will have speciation,” said University of Washington paleontologist Peter Ward. “But can we ever get off the Earth?”

Currently, the closest star system thought to have a planet is Epsilon Eridani, 10.5 light-years away. Even if spaceships could travel at 1 percent the speed of light — an incredible 6.7 million mph — it would take more than a millennium to get there.

Even Mars might be far enough: If humans established a permanent settlement there, the radically different living conditions would change the evolutionary equation. For example, those who are born and raised in one-third of Earth’s gravity could never feel at home on the old “home planet.” It wouldn’t take long for the new Martians to become a breed apart.

As for distant stars, the SETI Institute’s Seth Shostak has already been thinking through the possibilities:

Build a big ark: Build a spaceship big enough to carry an entire civilization to the destination star system. The problem is, that environment might be just too unnatural for natural humans. “If you talk to the sociologists, they’ll say that it will not work. … You’ll be lucky if anybody’s still alive after the third generation,” Shostak said.

Go to warp speed: Somehow we discover a wormhole or find a way to travel at relativistic speeds. “That sounds OK, except for the fact that nobody knows how to do it,” Shostak said.

Enter the Astrans: Humans are genetically engineered to tolerate ultra long-term hibernation aboard robotic ships. Once the ship reaches its destination, these “Astrans” are awakened to start the work of settling a new world. “That’s one possibility,” Shostak said.

The ultimate approach would be to send the instructions for making humans rather than the humans themselves, Shostak said.

“We’re not going to put anything in a rocket, we’re just going to beam ourselves to the stars,” he explained. “The only trouble is, if there’s nobody on the other end to put you back together, there’s no point.”

So are we back to square one? Not necessarily, Shostak said. Setting up the receivers on other stars is no job for a human, “but the machines could make it work.”

In fact, if any other society is significantly further along than ours, such a network might be up and running by now. “The machines really could develop large tracts of galactic real estate, whereas it’s really hard for biology to travel,” Shostak said.

It all seems inconceivable, but if humans really are extinction-proof — if they manage to survive global catastrophes, genetic upheavals and cybernetic challenges — who’s to say what will be inconceivable millions of years from now? Two intelligent species, human and machine, just might work together to spread life through the universe.

“If you were sufficiently motivated,” Shostak said, “you could in fact keep it going forever.”

![Brotherhood" (2006) [TV-Series]](http://photos1.blogger.com/x/blogger2/1421/379621144723082/211/z/425926/gse_multipart33129.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment