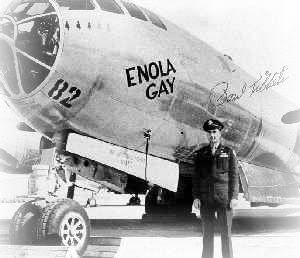

Paul Warfield Tibbets, Jr. (February 23, 1915 – November 1, 2007) was a brigadier general in the United States Air Force, best known for being the pilot of the Enola Gay, the first aircraft to drop an atomic bomb.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Tibbets

Paul Tibbets talks about the Hiroshima bombing

Paul Warfield Tibbets, Jr. (February 23, 1915 – November 1, 2007)

http://www.answers.com/topic/paul-tibbets?cat=technology

Biography

Early life

Tibbets was born in Quincy, Illinois, and was the son of Paul Warfield Tibbets and Enola Gay Tibbets (nee Haggard). Although born in Illinois, Tibbets was raised in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, where his father was a confections wholesaler. The family was listed there in the 1920 U.S. Federal Population Census. The 1930 Census indicates his family had moved and was living in Des Moines, Iowa at the time. Sometime later, the family moved to Florida. He attended the University of Florida in Gainesville and was an initiated member of the Epsilon Zeta Chapter of Sigma Nu Fraternity in 1934.

Military career

On February 25, 1937, he enlisted as a flying cadet in the Army Air Corps at Fort Thomas, Kentucky. He was commissioned a second lieutenant in 1938 and received his wings at Kelly Field, Texas. Tibbets was named commanding officer of the 340th Bomb Squadron, 97th Heavy Bomb Group flying B-17 Flying Fortresses in March, 1942. Based at RAF Polebrook, he piloted the lead bomber on the first Eighth Air Force bombing mission in Europe on August 17, 1942, and later flew combat missions in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations until returning to the U.S. to test fly B-29 Superfortresses. "By reputation", Tibbets was "the best flier in the Army Air Force".[1] One of those who confirmed this reputation was Dwight Eisenhower, for whom Tibbets served as a personal pilot at times during the war.

In September 1944 he was selected to command the project at Wendover Army Air Field, Utah, that became the 509th Composite Group, in connection with the Manhattan Project's Project Alberta.

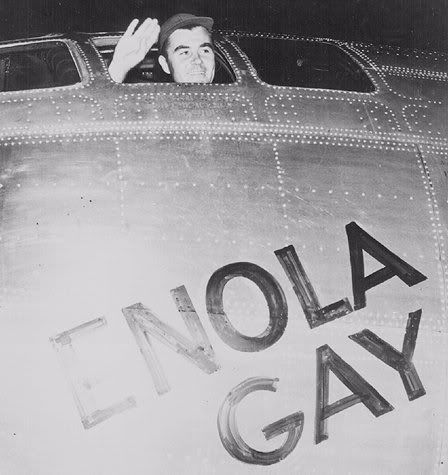

On August 5, 1945, Colonel Paul Tibbets formally named B-29 serial number 44-86292 Enola Gay after his mother (she was named after the heroine, Enola, of a novel her father had liked). On August 6 1945, the Enola Gay departed Tinian Island in the Marianas with Tibbets at the controls at 2:45 a.m. for Hiroshima, Japan. The atomic bomb, codenamed Little Boy, was dropped over Hiroshima at 8:15 a.m. local time, killing about 140,000 Japanese, with many more dying later.

The film Above and Beyond (1952) depicted the World War II events involving Tibbets, with Robert Taylor starring as Tibbets and Eleanor Parker as his first wife, Lucy. In 1980, a made-for-television movie aired, again telling a possibly more fictionalized version of the story of Tibbets and his men, with Patrick Duffy (Bobby Ewing from "Dallas") playing the part of Tibbets and Kim Darby as Lucy. The film was called, Enola Gay: The Men, the Mission, the Atomic Bomb. Tibbets was also portrayed in the films Day One and The Beginning or the End.

Tibbets' first marriage, to the former Lucy Wingate, ended in divorce in 1955;[2] he later remarried, to Andrea. In 1959, he was promoted to Brigadier General. He retired from the U.S. Air Force on August 31, 1966.

Later life

In the 1960s, Tibbets was posted as military attaché in India, but this posting was rescinded after protests. After retirement, he worked for Executive Jet Aviation, a Columbus, Ohio-based air taxi company, and was president from 1976 until he retired in 1987.

The U.S. government apologized when Japan complained in 1976 after Tibbets re-enacted the bombing at an air show in Texas, complete with mushroom cloud. Tibbets said it was not meant as an insult[3].

In 1995, he called a planned 50th anniversary exhibition of the Enola Gay at the Smithsonian Institution a "damn big insult",[3] putting the bombing in context of the suffering it caused.

An interview of Paul Tibbets can be seen in the 1982 movie Atomic Cafe. He was also interviewed in the 1970s British documentary series The World at War.

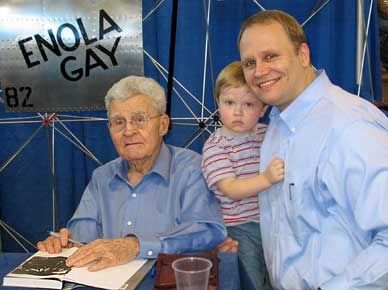

His grandson Lt. Col. Paul W. Tibbets, IV, as of 2006 is commander of the 393rd Bomb Squadron, flying the B-2 Spirit. The 393rd is one of two operational squadrons under the same unit his grandfather commanded, the 509th Bomb Wing.

Tibbets was interviewed extensively by Mike Harden of the Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch, and profiles appeared in the newspaper on anniversaries of the first dropping of an atomic bomb.

Tibbets expressed no regret regarding the decision to drop the bomb. In a 1975 interview he said: "I'm proud that I was able to start with nothing, plan it and have it work as perfectly as it did... I sleep clearly every night".[3] In March 2005, he stated “If you give me the same circumstances, hell yeah, I'd do it again.”

Death

Tibbets died in his Columbus, Ohio, home on November 1, 2007, at age 92.[3][4][5] He had suffered small strokes and heart failure in his final years and had been in hospice care.[6][7] Tibbets laid down in his will that there should be no funeral service after his death and no headstone for fear this might lead to demonstrations at his grave. He wanted to ensure that his resting place could never be a pilgrimage site for opponents of the use of nuclear weapons. Tibbets wanted to be cremated, and have his ashes dispersed into the waters of the English Channel.

The Official Website of Ret. General Paul W. Tibbets

http://www.enolagay.org/

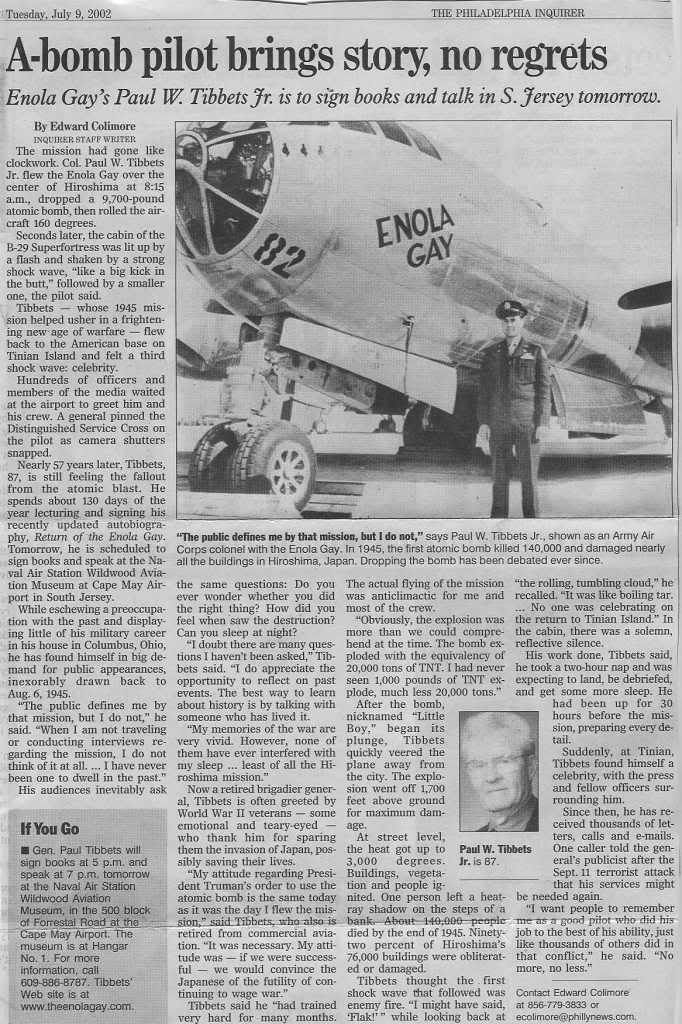

Pilot recalls A-bomb mission

http://www.jsonline.com/story/index.aspx?id=247168

General Paul Tibbets

http://www.theenolagay.com/

Paul Tibbets

Commanded Enola Gay, dropped first atomic bomb on Hiroshima

http://www.acepilots.com/usaaf_tibbets.html

The B-29 Superfortress, Enola Gay, rumbled down the the runway at Tinian, the forward American airbase in the Marianas, as close as the giant Boeing bombers could get to Japan's Home Islands. Heavily laden with the world's first operational atomic bomb, the B-29 shuddered and trembled as its four 2,000 horsepower Wright Cyclones roared. Its pilot, Paul Tibbets, thought briefly of the recent B-29 crashes on Tinian, and then focused on his mission.

"Dimples Eight Two to North Tinian Tower. Ready for takeoff on Runway Able." he radioed to the tower. The Enola Gay picked up speed, 75MPH, 100, then 125. Tibbets held the plane on the runway until it reached 155 MPH, then eased back on the yoke. Near the end of the 8500 foot runway, the B-29 lifted easily and steadily into the air. Tibbets checked his watch, which showed 2:45AM, the morning of August 6, 1945. In ten minutes they were over Saipan, at an altitude of 4,700 feet. In the pleasantly warm tropical night, during the thirteen hour flight, Tibbets and the other crewmen dozed off and on. It's possible that he thought back to another summer day, in 1927, over Miami's Hialeah racetrack.

Youth

Paul Tibbets was born Feb. 23, 1915, son of Enola Gay and Paul Warfield Tibbets in Quincy, Illinois. Attracted by the land boom, the Tibbets family moved to Florida when Paul was nine. On that memorable summer day, a barnstorming pilot, Doug Davis, let the twelve-year old Paul ride in his Waco 9 airplane and toss Baby Ruth candy bars to the crowds at Hialeah racetrack and Miami Beach. Tibbets always traced his interest in aviation to that day. The next year, 1928, he entered Western Military Academy (WMA), where Butch O'Hare attended at the same time. Here he learned many of the rituals of military life, such as hazing and room inspections where the inspector was likely to rub a white glove across the sole of his foot and issue a demerit for "dirty floors."

He enrolled in the University of Florida at Gainesville in 1933, more or less to follow his family's plan for him to pursue a medical career. With this goal still in mind, he transferred to University of Cincinnati after his sophomore year, where he continued to take flying lessons. After some major soul-searching, and a difficult conversation with his father, he decided that his heart was not in medicine, but rather in aviation.

Following this dream, he joined the Army Air Corps, and reported to Randolph Field in 1937. From his years at WMA, he was familiar with hazing, inspections, and other demands of military routine. He trained on PT-3's and BT-9's, the standard trainers of the day. He graduated first in his class, and unlike most of the other top pilots, he did not elect Pursuit, but rather multi-engine Observation duty, because he thought Observation would offer him more independence. From 1938 through 1940, while at Fort Benning, he flew O-46 and O-47 observation planes and B-10 bombers.

Here he met George Patton, then a Lieutenant Colonel, and destined to become the world-famous tank General in World War Two. While Tibbets was a lowly Second Lieutenant, they went skeet shooting together. Patton was a fierce competitor and "screamed in fury" at the few quarters he lost competing against Tibbets.

Tibbets learned a whole new approach to flying in 1941, when he began to fly the Army's new attack bomber, the A-20. While earlier bombers has sought refuge in altitude, the development of radar and the A-20's mission, forced the A-20 pilots to fly on the deck, barely 100 feet off the ground. He was flying over the skies of Georgia, listening to a commercial radio station, when he heard the news of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Amidst the rapidly changing priorities of early 1942, Tibbets (now a Captain) found himself in a squadron of B-18's destined for anti-submarine duty over the Atlantic. He soon transferred to the four-engine B-17 Flying Fortress, as commander of the 40th Squadron of the 97th Bomb Group (Heavy).

Flying B-17s over Europe

In the summer of 1942, he and the 97th flew their B-17s to the war: taking off from Bangor, Maine, stopping in Labrador, Greenland, and Iceland en route to their new base at Polebrook. The 97th BG served as the model for the famous movie Twelve O'Clock High; Tibbets, as a Major left in charge of the Group, was even depicted in the movie. Armstrong, the new CO of the 97th, appointed Tibbets his XO.

The first mission was scheduled for August 9, but a week of rain delayed it and increased the already considerable tension of the air crews.

On Aug. 17, 1942, he flew the B-17 Butcher Shop in the first daylight bombing raid by an American squadron over German-occupied Europe. On that morning, General Spaatz and various British brass, watched the take-off. 18 bombers flew that mission, the first of over 300,000 bomber sorties that the Eighth Air Force would make. Brigadier General Ira Eaker, head of VIII Bomber Command, also flew this mission in the Yankee Doodle and received official credit for "leading" it. They lifted off just after noon, climbed to 23,000 feet, and headed for Rouen and Buddicum, strongly escorted by RAF Spitfires. Three planes carried 1,100-pounds intended for the marshaling yards at Rouen; another nine planes carried 600-pound bombs for the repair shops at Buddicum. In mileage, it was a short mission. The bombers hit train repair shops near Rouen, and all returned safely.

For the next few months, they flew frequent missions, and continued training intensively in England, practicing gunnery over the Wash. Tibbets. Remembering his days cleaning the cannon at WMA, insisted that his crews disassemble thei1r machine guns, wash them thoroughly, and then lightly rub every part of the gun with gun oil, thus reducing the risk of the guns freezing or jamming at 20,000 feet.

In late 1942, as the Americans prepared for Operation "Torch," the invasion of North Africa, Tibbets was called on to fly General Mark Clark on a secret mission to meet with the French commander in Algiers. Flying the Red Gremlin, he flew Gen. Clark to Gibraltar, where a submarine picked the general up and brought him to Algeria. Clark's mission was successful; numerous French units cooperated with the Allied landing forces. Apparently the brass were impressed with Tibbets' general-ferrying skills; on Nov. 5, her flew General Eisenhower from England to Gibralter. With the plane crowded with staff officers, Ike sat on a two-by-four hastily installed in the cockpit, so he could get a pilot's eye view of the flight, which went off smoothly.

North Africa

After the Allies established themselves in Algeria, Tibbets' B-17 group was based first at Maison Blanche (outside Algiers), then at Tafaraoui ("deep and gooey"), and then at Biskra. In early 1943, he was transferred to the 12th Air Force, under General Jimmy Doolittle, where they wrestled with the challenges of the B-26 Marauder, a good plane, but one that was "a handful" for many pilots. It was during this time that Tibbets first crossed paths (and swords) with Lauris Norstad, a politically adept officer who, in the post-war years, stymied Tibbets' Air Force career.

The B-29 Superfortress

In July, 1943, he reported to "Boeing Wichita," one of the four plants devoted to the new bomber. Originally drawn up as early as 1940, the B-29 was an innovative aircraft: a fire control system that permitted one gunner to operate five pair of machine guns, a pneumatic bomb bay door, and completely pressurized crew compartments (connected by a crawl-through tube), tricycle landing gear. It was larger, faster, could fly higher & farther, and carried a larger bombload than a B-17. At Grand Island, Nebraska, he started a school to train B-29 flight instructors, where he connected with Frank Armstrong, his old commander at Polebrook, Among other things, they found that removing some of the heavy machine guns and ammo made a big difference in the Superforts' performance.

In Sept. 1944, he reported to Colorado Springs for a top secret assignment - to organize bombardment group to deliver the atomic bomb. Following a detailed personal interview, he was introduced to General Uzal Ent and Professor Norman Ramsey, who explained the project to him. Tibbets force, the 509th Composite Group, included 15 B-29's and 1,800 men. The 509th settled on Wendover, Utah as their base. Due to its remote location, it was ideal for security. From his old B-17 crew in Europe, he selected Tom Ferebee (bombardier), Sgt. George Caron (tail gunner), Dutch Van Kirk (navigator), and Sgt. Wyatt Duzenberry (flight engineer). These men were assigned to Tibbets' airplane. Bob Lewis flew as co-pilot. As Tibbets could get any men and any planes he needed, the 509th quickly filled out, and the entire organization was complete by Dec. 1944.

The primary challenge would be to drop the atomic bomb, without the shockwave destroying the B-29. The scientists estimated that a B-29 could survive the shockwave at a distance of eight miles. Flying at 31,000 feet, the B-29 would already be six miles in the air. To gain the extra distance, Tibbetts determined that a sharp 155 degree turn would be the best maneuver. In less than 2 minutes, the B-29 would reverse it direction and fly five miles; Another critical concern was accuracy; using the Norden bombsight, the bombardiers would have to put the bomb within 200 feet of the aiming point. Another challenge was to navigate over water and land; the transition could be disorienting. So Tibbets and his men trained for this navigation in Cuba. The Cuba training exercise gave him the opportunity to fly his mother, Enola Gay Tibbets, in a C-54 transport plane to visit him, surviving and even enjoying a turbulent flight, complete with St. Elmo's Fire.

Tinian - 509th Composite Group

By May, 1945, Tibbets and the 509th had moved out to the Pacific, to the island of Tinian in the Marianas. As it was shaped something like the island of Manhattan, the Army engineers named the base facilities with names like Broadway and Forty-second Street. Tibbets' group bivouacked in the "Columbia University district." Tinian was ideal; its 8,500 foot runways were among the longest in the world at the time. Tibbets ran into various confrontations, on issues from maintenance to training, stemming in part from the secrecy of the operations. He flew back and forth to the States three times between May and July, but missed the first atomic test at Alamogordo because he had to return to Tinian to persuade General Curtis LeMay not to switch the atomic mission to another outfit.

On July 26th, the cruiser Indianapolis dropped anchor off Tinian and unloaded a 15-foot wooden crate. Inside was the atomic bomb, complete except for a second slug of uranium that a B-29 later delivered. Having delivered its load without incident, Indianapolis moved on toward the Philippines. Though intelligence reports assured Captain Charles McVay that the route from Guam to Leyte was safe, there were Japanese submarines active in the area. Four days after departing Tinian, Indianapolis was sunk by a Japanese submarine.

The Mission

By early August, 1945, plans for the first atomic mission were set. Seven Boeing Superfortresses would take part, including the primary, a standby, a photo plane, one with scientific instruments to measure the blast, and three others that would scout ahead. Bombing would be visual, rather than by radar. Possible target cities included Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata, and Nagasaki. Until this time, Tibbets' own plane had been simply number 82, when he decided to name it Enola Gay, after his confidence-building and loving mother. Twelve men crewed the plane:

Capt. Robert Lewis - copilot

Maj. Thomas Ferebee - bombardier

Capt. Theodore Van Kirk - navigator

Lt. Jacob Beser - radar countermeasures

Capt. William "Deak" Parsons - weaponeer

2nd Lt. Maurice Jeppson - assistant weaponeer

Sgt. Joe Stiborik - radar

Staff Sgt. George Caron - tail gunner

Sgt. Robert Shumard - asst. flight engineer

Pfc. Richard Nelson - radio

Tech Sgt. Wayne Duzenberry - flight engineer

They got the word on Sunday morning, August 5. Conditions were go, and the next day would be the day. At the last minute, it was decided to complete the final assembly of the bomb in flight, thus eliminating the risk of it exploding if Enola Gay crashed on take-off. Navy Captain Deak Parsons, who had earlier opposed this idea, now suggested it, and persuaded the team that he could perform the difficult assembly in the cramped bomb bay of the B-29.

They loaded the bomb into the Enola Gay that afternoon. "Little Boy" was 12 feet long and 28 inches in diameter - bigger than any bomb Tibbetts had ever seen. Its explosive power equalled 20,000 tons of TNT; or roughly as much as two thousand Superfortresses could carry - all in a single bomb that weighed about 9,000 pounds. Deak Parsons practiced the delicate arming process. That night the crew was briefed, for the first time, on the nature of their weapon - an atomic bomb.

Chuck Sweeney, with the scientific instruments in the Great Artiste, would follow Tibbets' closely, duplicating his hairpin turn. George Marquardt's photo plane would stay far behind, out of range of the shock wave. The three weather planes, Claude Etherley's Strait Flush, John Wilson's Jabbitt III, and Ralph Taylor's Full House, would take off an hour ahead, to scout out the designated target cities. Every crewman carried a standard service pistol; Tibbets carried enough cyanide capsules for all. They started engines at 2:30 AM on the morning of August 6, 1945. Three hours after takeoff, they flew over Iwo Jima at dawn, where 5,500 Americans and 25,000 Japanese had died, so that the USAAF could use Iwo as an emergency landing field. They adjusted course and headed northwest. At 7:30, Deak Parsons completed his adjustments; the atomic bomb was live. They climbed slowly to their bombing altitude of 30,700 feet.

At 8:30 they received the coded message from Etherley's Strait Flush, flying over Hiroshima, "Y-3, Q-3, B-2, C-1." The message meant that cloud cover over Hiroshima, the primary target, was less than three-tenths. Tibbets gave the word to his crew, "It's Hiroshima." As they reached the coastline of Japan, no interceptors challenged them; the Japanese had become indifferent to small groups of B-29s. They crossed Shikoku and the Iyo Sea.

They looked down at the city below. The other crewmen verified that it was indeed Hiroshima. They spotted the Initial Point, or I.P. They turned and headed almost due west. Tom Ferebee peered into his Norden bombsight, and cranked in the information to correct for the south wind. Tibbets reminded the crew to put on their heavy dark Polaroid goggles, to shield their eyes from the blinding blast. It had been calculated to have the intensity of ten suns. They easily spotted the distinctive T-shaped bridge that was their primary. 90 seconds before drop, he turned the controls over to Tom Ferebee, the bombardier. At 9:15AM (8:15 Hiroshima time), they dropped "Little Boy" and made a 155 degree diving turn to the right. Unable to fly the plane with the dark goggles, they shoved them aside.

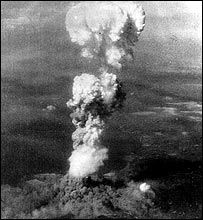

43 seconds later, a tingling in Tibbets' teeth told him of the Hiroshima explosion: the bomb's radioactive forces interacting with his fillings. The bomb exploded at 1890 feet above the ground. Bob Caron, the tail gunner was the only crew member to see the fireball. Even wearing the goggles, he thought he was blinded. The plane raced away, while the shockwave from the explosion raced toward them at 1,100 feet per second. When the shockwave hit, it felt like a near-miss from flak. The mushroom cloud boiled up, 45,000 feet high, three miles above them, and it was still rising. They flew away, shocked and horrified at the sight below. The city had completely disappeared under a blanket of smoke and fire. They radioed back to headquarters that the primary target had been bombed visually with good results.

The mushroom cloud over Hiroshima was visible for an hour and a half as they flew southward back to Tinian. The crew talked about the effect of the atomic bomb on the war. They thought that perhaps the Japs would "throw in the sponge" even before they landed. Twelve hours after they had taken off, Tibbets and the crew of the Enola Gay touched down, to be greeted by all the military brass that could be mustered: General Carl Spaatz, commander of the Strategic Air Force; General Nathan Twining, chief of the Marianas Air Force; General Thomas F. Farrell and Rear Admiral W.R.E. Purnell, both with the atomic development project; and General John Davies, 313th Wing Commander. Spaatz pinned a Distinguished Service Cross on Tibbets as he descended from the plane.

After the welcoming formalities, they were debriefed and given a quick medical checkup. The interviewers were skeptical of their accounts of the blast. The news of the atomic bomb was promptly announced to the world. The Japanese were given an ultimatum, to accept the Potsdam call for unconditional surrender, or face further atomic attacks. Three days later, Chuck Sweeney, in Bock's Car, dropped the second atomic bomb on Nagasaki.

After the War

Not long after the surrender, Tibbets inspected the damage done to Nagasaki. He stayed in the Air Force, and participated in the development of the B-47, our first all-jet bomber. He learned to fly jets with Pat Fleming, a 19-kill Navy ace. In the early 1950's, he flew B-47's for three years. He advised on the making of the movie "Above and Beyond," and was pleased that the famous actor, Robert Taylor, played him. From the 1950's through the 1960's he had a number of overseas assignments, including France and India. After his retirement from the Air Force, he became president of Executive Jet Aviation in Columbus, Ohio.

Still no regrets for frail Enola Gay pilot (Col. Paul Tibbets)

http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/1458133/posts

The mind of the pilot whose B-29 dropped the first atomic bomb often seems more prisoner than resident of his bantamweight body wracked by injury, ailments and 90 years of living.

In the months before today’s 60 th anniversary of his mission to Hiroshima, Paul Tibbets was hobbled by a pair of spills that fractured two vertebrae. For a while, his appetite disappeared, his weight dropped alarmingly, and he railed against the fates torturing him in his waning years.

"I’ve never been incapacitated a damned day of my life," he groused two months ago, daily downing enough OxyContin to make it out of bed and to an easy chair from which he stared at a television he could barely hear.

Yet by August’s first days, the fractures had mended, an orthopedic brace was gone, and his hallmark feistiness had returned.

"He is still the general, and I am the Pfc.," said Andrea, the old pilot’s wife of 51 years. "He went up in rank over the years, but I have stayed a Pfc."

The traits that sometimes have made him a difficult mate — his single-mindedness, drive, tenacity and intolerance for mediocrity — endeared him to the military leadership that chose him to command the first atomic-bomb mission.

"Paul’s mind works like a com- puter," said Gerry Newhouse, Tibbets’ former business manager and friend. "Eisenhower told (historian) Stephen Ambrose that Tibbets was the best bomber pilot in World War II.

"His crews respected him. Psychologically, he could handle the aftereffects of such a mission. For the last 60 years, he has had to deal with the controversy."

"I knew when I got the assignment it was going to be an emotional thing," Tibbets acknowledged Wednesday, noting of his crew, "We had feelings, but we had to put them in the background. We knew it was going to kill people right and left. But my one driving interest was to do the best job I could so that we could end the killing as quickly as possible."

On Aug. 3, 1945, he was told to proceed with "Special Bombing Mission No. 13."

Less than three hours before takeoff, the 30-year-old colonel and his crew sat down to a midnight breakfast at a Tinian Island mess hall nicknamed the "Dogpatch Inn."

When the Enola Gay, named for Tibbets’ mother, roared down the runway in the predawn of Aug. 6, Tibbets was carrying his favorite smoking pipe, a few cigars and a small cardboard pillbox holding a dozen cyanide capsules, in case the crew had to bail out over enemy territory.

Mission from childhood

The seed of Tibbets’ ultimate rendezvous with history likely was planted before he was a teenager.

He was born in Quincy, Ill., and lived briefly in Iowa before his father moved the family to Miami. Tibbets, then 12, was hanging out at his father’s business, Tibbets & Smith Wholesale Confectioners, when a barnstorming pilot entered the offices and announced that he needed an assistant for a bombing mission. While he piloted the plane over Miami’s large public venues, an assistant would drop paper-parachuted samples of Baby Ruth candy bars to the crowd below.

Tibbets volunteered against the wishes of his father, who already had determined that his son was going to be a doctor.

The young man later recalled the week he spent dropping sweets from the back seat of a biplane, "No Arabian prince ever rode a magic carpet with a greater delight or sense of superiority to the rest of the human race."

He was sent to military school and then entered the University of Florida, often spending more time at the Gainesville airstrip than in class.

After his sophomore year, he was pressed by his father to transfer to the University of Cincinnati, where a family friend and physician could help cultivate his interest in medical school.

It had the opposite effect. After a brief stint as an aide at the physician’s two venereal-disease clinics, Tibbets — though deft with a syringe and needle — decided that there had to be something better in life than administering arsenic treatments to syphilitics. He applied to become an aviation cadet in the Army Air Corps.

By late 1941, Tibbets had earned his commission and wings and, on Dec. 7, was flying his A-10 attack bomber to Savannah, Ga., after participating in a war-games mock surprise attack on ground troops at Fort Bragg. Homing in on the signal of a radio station’s broadcast tower, he listened as a somber voice interrupted the music to announce the attack on Pearl Harbor.

"I thought, ‘Boy, Orson Welles is at it again,’ " he recalled, referring to the Welles broadcast of War of the Worlds.

When the U.S. entered the war, Tibbets flew B-17 sorties in the North Africa campaign, later leading the first daylight B-17 raid across the English Channel. He was on a B-17 mission in late 1942 when enemy flak exploded part of his instrument panel and peppered him with shrapnel.

Tibbets says today that his missions over occupied Europe in his beloved Red Gremlin, though fraught with peril, were the most gratifying of all his military flying.

A few months after he was wounded, Tibbets was ordered back to the States to begin testing the new Boeing B-29. By 1944, he knew the plane’s capabilities as well or better than the company that built it, but some of the young pilots who would form his 509 th Composite Bomb Group thought the craft dangerous and unwieldy.

To show the younger fliers that their fears were unfounded, Tibbets recruited two Women’s Air Service Pilots to train on the B-29. To the embarrassment of the male pilots, they maneuvered the B-29 superbly, even with two of the four engines shut off.

Visit from the feds

In 1944, Tibbets learned that the FBI was nosing around his old neighborhood regarding his fitness for a top-secret clearance.

They unearthed his lone arrest, at 19, after a Surfside, Fla., police officer had caught Tibbets and his date in the back seat of a car on a remote stretch of beach.

When Gen. Uzal Ent informed Tibbets that he had been selected for the atomic-bomb mission, the general cautioned, "If this is a success, you’ll be a hero. If not, it’s possible that you could wind up in prison."

Tibbets didn’t know which it would be when, 10 miles from Hiroshima, his bombardier, Maj. Thomas Ferebee, broke in on the intercom: "OK, I’ve got the bridge."

A T-shaped span over the Ota River was the target.

"As we approached the aiming point," Tibbets remembered, "I watched for the first signs of anti-aircraft fire or fighter planes."

There were none.

When the bomb christened "Little Boy" tumbled from the belly of the Enola Gay, the plane’s nose, unburdened of 8,900 pounds in an instant, jerked upward. Tibbets swung the craft into a 155-degree diving turn to put as much distance as possible between the impending blast and his bomber. Forty-three seconds later, the sky lit up with a terrible flash.

"If Dante had been on the plane with us, he would have been terrified," Tibbets later said.

"My God," co-pilot Capt. Robert Lewis scribbled in his flight log.

Death estimates have varied widely. Some say 80,000 is a reliable figure, while noting that tens of thousands of others perished by year’s end from the effects of radiation. The dead included 20,000 Koreans the Japanese had enslaved for war work.

No escape from war

Tibbets remained in the Air Force until 1966, leaving the service as a brigadier general.

Not long after, he went to work for Executive Jet Aviation, a global all-jet, air-taxi company based in Columbus. His first assignment was in Geneva, Switzerland. He spent two years there before moving to Columbus and, in 1976, becoming the company’s president.

Throughout the ’60s and ’70s, Tibbets endured urban legends suggesting, among other falsehoods, that he was in prison or had died at his own hand.

"They said I was crazy," he complained, "said I was a drunkard, in and out of institutions. At the time, I was running the National Crisis Center at the Pentagon."

Tibbets retired from Executive Jet in 1987 and, since then, has been both hot and cold about his notoriety. He was active behind the scenes in the protest of the National Air and Space Museum’s 1995 exhibit of part of the Enola Gay’s fuselage, where the initial presentation suggested that the atomic bomb crews were agents of a vengeful nation. The script ultimately was changed.

In late 2003, a fully restored Enola Gay went on display in a companion facility to the air and space museum in Chantilly, Va.

"I wanted to climb in and fly it," Tibbets said.

The exhibit opening was his last major public hurrah.

This past spring, he gave up driving after his falls and what doctors think to have been two minor strokes. He convalesces in a home guarded by a yammering chihuahua named Lolita and looks out on a front yard whose chief adornment is a weeping Japanese cherry.

At the 60 th anniversary, Tibbets said of his notoriety, "It’s kind of getting old, but then so am I."

He waved off other requests to be interviewed, in part because of his health and for weariness of suffering a new crop of reporters thinking they are the first to ask, "Any regrets?"

His answer always has been a resounding "Hell, no," lately modified to lament, "The guys who appreciated that I saved their asses are mostly dead now."

He is, today, a man untroubled with the certainty of joining their ranks.

"I don’t fear a goddamn thing," he said. "I’m not afraid of dying.

"As soon as the death certificate is signed, I want to be cremated. I don’t want a funeral. I don’t want to be eulogized. I don’t want any monuments or plaques.

"I want my ashes scattered over water where I loved to fly."

The English Channel.

Tibbets’ eyes brimmed for a moment when he pondered the absent friends who formed the unshakeable brotherhood that become the only religion some men ever know.

"That’s the first time I’ve seen that kind of emotion in 51 years," a clearly stunned Andrea said.

"He doesn’t want to have a tombstone or monument in a cemetery, because that would create a controversy," friend Gerry Newhouse said.

One of the candidates for the eventual task of spreading Tibbets’ ashes likely might be his grandson and namesake, Lt. Col. Paul Tibbets IV, a B-2 mission command pilot.

His Air Force nickname is "Nuke."

Pilot of Plane That Dropped A-Bomb Dies

Pilot of B-29 Bomber That Dropped Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima Dies at 92

http://abcnews.go.com/US/wireStory?id=3806264

Paul Tibbets, who etched his mother's name Enola Gay into history on the nose of the B-29 bomber he flew to drop the atomic bomb over Hiroshima, died Thursday after six decades of steadfastly defending the mission. He was 92.

Throughout his life, Tibbets seemed more troubled by other people's objections to the bomb than by him having led the crew that killed tens of thousands of Japanese in a single stroke. The attack marked the beginning of the end of World War II.

Tibbets grew tired of criticism for delivering the first nuclear weapon used in wartime, telling family and friends that he wanted no funeral service or headstone because he feared a burial site would only give detractors a place to protest.

And he insisted he slept just fine, believing with certainty that using the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki saved more lives than they erased because they eliminated the need for a drawn-out invasion of Japan.

"He said, 'What they needed was someone who could do this and not flinch and that was me,'" said journalist Bob Greene, who wrote the Tibbets biography, "Duty: A Father, His Son, and the Man Who Won the War."

Tibbets, 92, died at his Columbus home after a two-month decline caused by a variety of health problems, said Gerry Newhouse, a longtime friend.

"I'm not proud that I killed 80,000 people, but I'm proud that I was able to start with nothing, plan it and have it work as perfectly as it did," he said in a 1975 interview.

"You've got to take stock and assess the situation at that time. We were at war. ... You use anything at your disposal."

He added: "I sleep clearly every night."

Filmmaker Ken Burns said Tibbets' life "helps to take this incredible, gigantic event and personalize it. This is a real human being who changed the course of the world inexorably on that August morning."

Paul Warfield Tibbets Jr. was born Feb. 23, 1915, in Quincy, Ill., and spent most of his boyhood in Miami. He was a student at the University of Cincinnati's medical school when he decided to withdraw in 1937 to enlist in the Army Air Corps.

"I knew when I got the assignment it was going to be an emotional thing," Tibbets told The Columbus Dispatch for a story on the 60th anniversary of the bombing. "We had feelings, but we had to put them in the background. We knew it was going to kill people right and left. But my one driving interest was to do the best job I could so that we could end the killing as quickly as possible."

Tibbets, a 30-year-old colonel at the time, and his crew of 13 dropped the five-ton "Little Boy" bomb over Hiroshima the morning of Aug. 6, 1945. The blast killed or injured at least 140,000.

Three days later, the United States dropped a second atomic bomb on Nagasaki, killing at least 60,000 people. Tibbets did not fly in that mission. The Japanese surrendered a few days later.

"It did in fact end the war," said Morris Jeppson, the officer who armed the bomb during the Hiroshima flight. "Ending the war saved a lot of U.S. armed forces and Japanese civilians and military. History has shown there was no need to criticize him."

Former U.S. Sen. John Glenn, a former Marine fighter pilot, said people who criticized Tibbets for piloting the plane that dropped the bomb failed to recognize that an allied invasion of Japan, which the bomb helped avert, would have resulted in the deaths of several million people.

"It wasn't his decision. It was a presidential decision, and he was an officer that carried out his duty," Glenn said. "It's a horrible weapon, but war is pretty horrible, too."

The head of the Japan Congress Against A- and H-Bombs rejected the idea that the bombing saved lives.

"What Mr. Tibbits did should never be forgiven," said Takashi Mukai, whose mother, a nurse, suffered lifelong effects of radiation as she treated bombing victims. "His actions led to the indiscriminate killing of so many, from the elderly to young children.

"Nevertheless, I would like to express my condolences to his family, and pray for his soul," he said. "What's important now is that we move toward a world free of nuclear weapons."

Tibbets retired from the Air Force as a brigadier general in 1966. He moved to Columbus, where he ran an air taxi service until he retired in 1985.

Tibbets said in 2005 that after the war he was dogged by rumors claiming he was in prison or had committed suicide.

"They said I was crazy, said I was a drunkard, in and out of institutions," he said. "At the time, I was running the National Crisis Center at the Pentagon."

In 1976, he was criticized for re-enacting the bombing during an appearance at a Harlingen, Texas, air show. As he flew a B-29 Superfortress over the show, a bomb set off on the runway below created a mushroom cloud.

He said the display "was not intended to insult anybody," but the Japanese were outraged. The U.S. government later issued a formal apology.

Tibbets again defended the bombing in 1995, when an outcry erupted over a planned 50th anniversary exhibit of the Enola Gay at the Smithsonian Institution.

In his later years, he frequently accepted speaking invitations and signed books on the bombing of Hiroshima, said granddaughter Kia Tibbets.

Author Richard Rhodes said Tibbets' feelings about the bombing he helped plan embodied public opinion at the time.

"He was so characteristic of that generation. He was a man who took great pride in what he did during the war, including the atomic bombing," said Rhodes, who wrote "The Making of the Atomic Bomb."

"It's hard for people today to think about the atomic bombings without feeling they were just out and out atrocities, but people at the time had a very different sense of what they needed to do," Rhodes said.

Tibbets told the Dispatch in 2005 he wanted his ashes scattered over the English Channel, where he loved to fly during the war.

Survivors include his wife, Andrea, and three sons, Paul, Gene and James, as well as a number of grandchildren and great-grandchildren. A grandson named after Tibbets followed his grandfather into the military as a B-2 bomber pilot currently stationed in Belgium.

Paul W. Tibbets Jr., Pilot of Enola Gay, Dies at 92

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/01/obituaries/01cnd-tibbets.html?ex=1351569600&en=37031c28cdbf14ea&ei=5088&partner=rssnyt&emc=rss

Brig. Gen. Paul W. Tibbets Jr., the commander and pilot of the Enola Gay, the B-29 Superfortress that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima in the final days of World War II, died today at his home in Columbus, Ohio. He was 92.

His death was announced by a friend, Gerry Newhouse, who said General Tibbets had been in decline with a variety of ailments. Mr. Newhouse said General Tibbets had requested that there be no funeral or headstone, fearing it would give his detractors a place to protest.

In the hours before dawn on Aug. 6, 1945, the Enola Gay lifted off from the island of Tinian carrying a uranium atomic bomb assembled under extraordinary secrecy in the vast endeavor known as the Manhattan Project.

Six and a half hours later, under clear skies, then-Colonel Tibbets, of the Army Air Forces, guided the four-engine plane he had named in honor of his mother toward the bomb’s aiming point, the T-shaped Aioi Bridge in the center of Hiroshima, the site of an important Japanese army headquarters.

At 8:15 a.m. local time, the bomb known to its creators as Little Boy dropped free at an altitude of 31,000 feet. Forty-three seconds later, at 1,890 feet above ground zero, it exploded in a nuclear inferno that left tens of thousands dead and dying and turned much of Hiroshima, a city of some 250,000 at the time, into a scorched ruin.

Colonel Tibbets executed a well-rehearsed diving turn to avoid the blast effect.

In his memoir “The Tibbets Story,” he told of “the awesome sight that met our eyes as we turned for a heading that would take us alongside the burning, devastated city.”

“The giant purple mushroom, which the tail-gunner had described, had already risen to a height of 45,000 feet, 3 miles above our own altitude, and was still boiling upward like something terribly alive,” he remembered.

Three days later, an even more powerful atomic bomb — a plutonium device — was dropped on Nagasaki from a B-29 flown by Maj. Charles W. Sweeney.

On Aug. 15, Japan surrendered, bringing World War II to an end.

The crews who flew the atomic strikes were seen by Americans as saviors who had averted the huge casualties that were expected to result from an invasion of Japan. But questions were eventually raised concerning the morality of atomic warfare and the need for the Truman administration to drop the bomb in order to secure Japan’s surrender.

General Tibbets never wavered in defense of his mission.

“I was anxious to do it,” he told an interviewer for the documentary “The Men Who Brought the Dawn,” marking the 50th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing. “I wanted to do everything that I could to subdue Japan. I wanted to kill the bastards. That was the attitude of the United States in those years.” “I have been convinced that we saved more lives than we took,” he said, referring to both American and Japanese casualties from an invasion of Japan. “It would have been morally wrong if we’d have had that weapon and not used it and let a million more people die.”

Paul Warfield Tibbets Jr. was born on Feb. 23, 1915, in Quincy, Ill. His father was a salesman in a family grocery business. His mother, the former Enola Gay Haggard, grew up on an Iowa farm and was named for a character in a novel her father was reading shortly before she was born.

The family moved to Miami, and at age 12 Paul Tibbets took a ride with a barnstorming pilot and dropped Baby Ruth candy bars on Hialeah race track in a promotional stunt for the Curtiss Candy Company. He was thrilled by flight, and though his father wanted him to be a doctor, his mother encouraged him to pursue his dream.

After attending the University of Florida and University of Cincinnati, he joined the Army Air Corps in 1937.

On Aug. 17, 1942, he led a dozen B-17 Flying Fortresses on the first daylight raid by an American squadron on German-occupied Europe, bombing railroad marshaling yards in the French city of Rouen. He flew Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower to Gibraltar in November 1942 en route to the launching of Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa, and participated in the first bombing missions of that campaign.

After returning to the United States to test the newly developed B-29, the first intercontinental bomber, he was told in September 1944 of the most closely held secret of the war: scientists were working to harness the power of atomic energy to create a bomb of such destruction that it could end the war.

He was ordered to find the best pilots, navigators, bombardiers and supporting crewmen and mold them into a unit that would deliver that bomb from a B-29.

In his memoir “Now It Can Be Told,” Lt. Gen. Leslie R. Groves Jr., who oversaw the Manhattan Project, said that Colonel Tibbets had been selected to train the crews because “he was a superb pilot of heavy planes, with years of military flying experience, and was probably as familiar with the B-29 as anyone in the service.”

He took command of the newly created 509th Composite Group, a unit of 1,800 men who trained amid extraordinary security at Wendover Field in Utah.

In the summer of 1945, Colonel Tibbets oversaw his unit’s transfer for additional training on Tinian in the Northern Marianas. On July 16, an atomic bomb was successfully tested in the New Mexico desert, and when Japan ignored a surrender demand issued at the Potsdam Conference, Colonel Tibbets completed final preparations to drop a uranium bomb.

The Enola Gay, carrying a crew of 12, carried out a flawless mission, delivering the bomb on time, almost precisely on target and with no opposition from Japanese fighters. When the plane returned to Tinian, Gen. Carl Spaatz, the commander of the Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific, presented Colonel Tibbets with the Distinguished Service Cross, the Army Air Forces’ highest award for valor after the Medal of Honor.

Remaining in the military after the war, he served with the Strategic Air Command, the nation’s nuclear bombing force, and became a one-star general. After retiring in 1966, he was president of Executive Jet Aviation, an air-taxi company in Columbus, Ohio.

His marriage to the former Lucy Wingate ended in divorce in 1955. Survivors include his wife, the former Andrea Quattrehomme, two sons from his first marriage, Paul III and Gene, and a grandson, Col. Paul Tibbets IV. General Tibbets’s s wartime experiences were dramatized in the 1952 MGM movie “Above and Beyond,” in which he was portrayed by Robert Taylor.

As the years passed, he became a symbolic figure in the controversy over use of the atomic bomb.

While he was deputy chief of the United States military supply mission in India in 1965, a pro-Communist newspaper denounced him as “the world’s greatest killer.” In 1976, he drew a protest from Hiroshima’s mayor, Takeshi Araki, when he flew a B-29 in a simulation of the Hiroshima bombing at an air show in Texas.

In 1995, the Enola Gay’s forward fuselage and some other parts of the plane were displayed at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington.

Veterans’ groups and some members of Congress denounced a proposed text for the exhibition, contending it portrayed the Japanese as victims and the Americans as vengeful. Their protest resulted in the resignation of the museum’s director, Dr. Martin Harwit, and the withdrawal of almost all material in the exhibition providing visitors with historical background. General Tibbets’s plane — the name Enola Gay freshly repainted — was left to speak for itself.

In December 2003, the Enola Gay found another home. Fully restored and completely assembled, it went on display at the newly opened Smithsonian air museum branch outside Dulles Airport in Virginia.

The previous spring, General Tibbets visited the Virginia Aviation Museum in Richmond. “There is no morality in war,” The Virginian-Pilot quoted him as saying then. “A way must be found to eliminate war as a means of settling quarrels between nations.”

At the same time, General Tibbets expressed no regrets over his role in the launching of atomic warfare. “I viewed my mission as one to save lives,” he said. “I didn’t bomb Pearl Harbor. I didn’t start the war, but I was going to finish it.”

World War II Weekend in Reading, PA with Paul Tibbets

Hiroshima bomb pilot dies aged 92

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/7073441.stm

The commander of the B-29 plane that dropped the first atomic bomb, on Hiroshima in Japan, has died.

Paul Warfield Tibbets Jr died at his home in Columbus, Ohio, aged 92.

The five-ton "Little Boy" bomb was dropped on the morning of 6 August 1945, killing about 140,000 Japanese, with many more dying later.

On the 60th anniversary of the bombing, the three surviving crew members of the Enola Gay - named after Tibbet's mother - said they had "no regrets".

'No headstone'

A friend of the retired brigadier-general told AP news agency that Paul Tibbets had died after a two-month decline in health.

Gen Tibbets had asked for no funeral nor headstone as he feared opponents of the bombing may use it as a place of protest, the friend, Gerry Newhouse, said.

The bombing of Hiroshima marked the beginning of the end of the war in the Pacific.

Japan surrendered shortly after a second bomb was dropped, on Nagasaki, three days later.

On the 60th anniversary of Hiroshima, the surviving members of the Enola Gay crew - Gen Tibbets, Theodore J "Dutch" Van Kirk (the navigator) and Morris R Jeppson (weapon test officer) said: "The use of the atomic weapon was a necessary moment in history. We have no regrets".

Gen Tibbets said then: "Thousands of former soldiers and military family members have expressed a particularly touching and personal gratitude suggesting that they might not be alive today had it been necessary to resort to an invasion of the Japanese home islands to end the fighting."

Air show

Paul Warfield Tibbets Jr was born in Quincy, Illinois, in 1915 and spent most of his youth in Miami.

He enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1937 and led bombing operations in Europe before returning to test the Superfortress.

He retired from the forces in 1966.

In a 1975 interview he said: "I'm proud that I was able to start with nothing, plan it and have it work as perfectly as it did... I sleep clearly every night."

In 1976, Gen Tibbets was criticised for re-enacting the bombing at an air show in Texas.

A mushroom cloud was set off as he over flew in a B-29 Superfortress in a stunt that outraged Japan. Gen Tibbets said it was not meant as an insult but the US government formally apologised.

In 1995, Gen Tibbets denounced as a "damn big insult" a planned 50th anniversary exhibition of the Enola Gay at the Smithsonian Institution that put the bombing in context of the suffering it caused.

He and veterans groups said too much attention was being paid to Japan's suffering and not enough to its military brutality.

Paul Tibbets, A-Bomb Pilot, Dies

http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,1678775,00.html

Paul Tibbets, who piloted the B-29 bomber Enola Gay that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, died Thursday. He was 92 and insisted almost to his dying day that he had no regrets about the mission and slept just fine at night.

Tibbets died at his Columbus home, said Gerry Newhouse, a longtime friend. He suffered from a variety of health problems and had been in decline for two months. He requested no funeral and no headstone, fearing it would provide his detractors with a place to protest, Newhouse said.

Tibbets' historic mission in the plane named for his mother marked the beginning of the end of World War II and eliminated the need for what military planners feared would have been an extraordinarily bloody invasion of Japan. It was the first use of a nuclear weapon in wartime.

The plane and its crew of 14 dropped the five-ton "Little Boy" bomb on the morning of Aug. 6, 1945. The blast killed 70,000 to 100,000 people and injured countless others.

Three days later, the United States dropped a second nuclear bomb on Nagasaki, Japan, killing an estimated 40,000 people. Tibbets did not fly in that mission. The Japanese surrendered a few days later, ending the war.

"I knew when I got the assignment it was going to be an emotional thing," Tibbets told The Columbus Dispatch for a story published on the 60th anniversary of the bombing. "We had feelings, but we had to put them in the background. We knew it was going to kill people right and left. But my one driving interest was to do the best job I could so that we could end the killing as quickly as possible."

Tibbets, then a 30-year-old colonel, never expressed regret over his role. He said it was his patriotic duty and the right thing to do. "I'm not proud that I killed 80,000 people, but I'm proud that I was able to start with nothing, plan it and have it work as perfectly as it did," he said in a 1975 interview. "You've got to take stock and assess the situation at that time. We were at war. ... You use anything at your disposal."

He added: "I sleep clearly every night."

Paul Warfield Tibbets Jr. was born Feb. 23, 1915, in Quincy, Ill., and spent most of his boyhood in Miami.

He was a student at the University of Cincinnati's medical school when he decided to withdraw in 1937 to enlist in the Army Air Corps.

Tibbets retired from the Air Force as a brigadier general in 1966. He later moved to Columbus, where he ran an air taxi service until he retired in 1985.

He told the Dispatch in 2005 that he wanted his ashes scattered over the English Channel, where he loved to fly during the war.

Newhouse, Tibbets' longtime friend, confirmed that Tibbets wanted to be cremated, but he said relatives had not yet determined how he would be laid to rest.

Final secret of A-bomb pilot Paul Tibbets revealed

http://www.news.com.au/heraldsun/story/0,21985,22692627-663,00.html

PAUL Tibbets, the US pilot of the B-29 bomber Enola Gay which dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, wanted a secret funeral.

The former brigadier-general died at his Columbus, Ohio, home yesterday, aged 92.

He insisted almost to his dying day that he had no regrets about the mission and slept well at night.

Long-time friend Gerry Newhouse said Mr Tibbets suffered from a variety of health problems and had been in decline for two months.

He said Mr Tibbets had requested no funeral and no headstone, fearing it would provide his detractors with a place to protest.

In Tokyo, Japanese survivors of the A-bomb attack on Hiroshima voiced regret Mr Tibbets had died without saying sorry.

The bombing led to the end of World War II, but at a horrific price: 140,000 dead immediately and 80,000 other Japanese succumbing in the aftermath, according to Hiroshima officials.

"He did not apologise, arguing, like the American government, that the bombing saved millions of American and Japanese lives by ending the war," said Nori Tohei, 79, who survived the bombing of the western Japanese city.

"But I wanted him to visit Hiroshima and take a direct look at what he did as a human being," said Mr Tohei, who co-chairs the Japan Confederation of A and H-Bomb Sufferers Organisations and now lives in Tokyo.

"He was following orders as a military man, but I wanted him to recognise it (the bombing) was a mistake and apologise to those who were killed or were long suffering side-effects."

The then-Colonel Tibbets' historic mission in the plane named for his mother eliminated the need for what military planners feared would have been an extraordinarily bloody invasion of Japan. It was the first use of a nuclear weapon in wartime.

The plane and its crew of 14 dropped the five-tonne "Little Boy" bomb on the morning of August 6, 1945.

Three days later, the US dropped a second nuclear bomb on Nagasaki, Japan, killing about 40,000 people. Col Tibbets did not fly in that mission. Japan surrendered a few days later.

Mr Tibbets retired from the air force as a brigadier-general in 1966. He later ran an air taxi service.

He said in 2005 he wanted his ashes scattered over the English Channel, where he loved to fly during the war.

Mr Newhouse, Mr Tibbets' longtime friend, said relatives had not yet determined how he would be laid to rest.

nuclear bombings of hiroshima and nagasaki

![Brotherhood" (2006) [TV-Series]](http://photos1.blogger.com/x/blogger2/1421/379621144723082/211/z/425926/gse_multipart33129.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment