The Great Chicago Fire was a conflagration that burned from Sunday October 8 to early Tuesday October 10, 1871, killing hundreds and destroying about four square miles in Chicago, Illinois. Though the fire was one of the largest U.S. disasters of the 19th century, the rebuilding that began almost immediately spurred Chicago's development into one of the most populous and economically important American and international cities.

On the municipal flag of Chicago, the second star commemorates the fire.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1871_Great_Chicago_Fire

The Great Chicago Fire was a conflagration that burned from Sunday October 8 to early Tuesday October 10, 1871, killing hundreds and destroying about four square miles in Chicago, Illinois. Though the fire was one of the largest U.S. disasters of the 19th century, the rebuilding that began almost immediately spurred Chicago's development into one of the most populous and economically important American and international cities.

http://www.answers.com/topic/great-chicago-fire

The fire's origin

The fire started at about 9 P.M on Sunday, October 8, in or around a small shed that bordered the alley behind 137 DeKoven Street. The traditional account of the origin of the fire is that it was started by a cow kicking over a lantern in the barn owned by Patrick and Catherine O'Leary, but Michael Ahern, the Chicago Republican reporter who created the cow story, admitted in 1893 that he had made it up because he thought it would make colorful copy.[1]

It was aided by the city's overuse of wood for building, the strong northwesterly winds, and a drought before the fire. The city also made fatal errors by not reacting soon enough and citizens by not caring about the fire when it began. The firefighters were also exhausted from fighting a fire that happened the day before.

Spread of the blaze

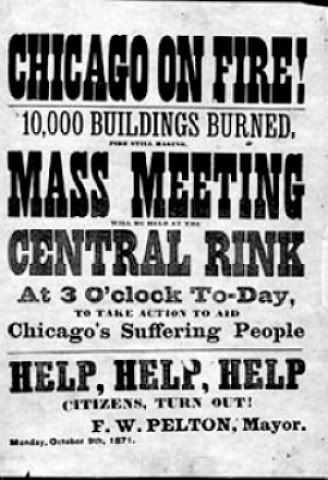

When the fire broke out, neighbors hurried to protect the O'Learys' house in front of the cowshed from the blaze; the house actually did survive with only minor damage. However, the city's fire department didn't receive the first alarm until 9:40 p.m., when a fire alarm was pulled at a pharmacy. The fire department was alerted when the fire was still small, but the guard on duty did not respond as he thought that the glow in the sky was from the smoldering flames of a fire the day before. When the blaze got bigger, the guard realized that there actually was a new fire and sent firefighters, but in the wrong direction.

Soon the fire had spread to neighboring frame houses and sheds. Superheated winds drove flaming brands northeastward. People still did not worry, even though in fact they were in danger.

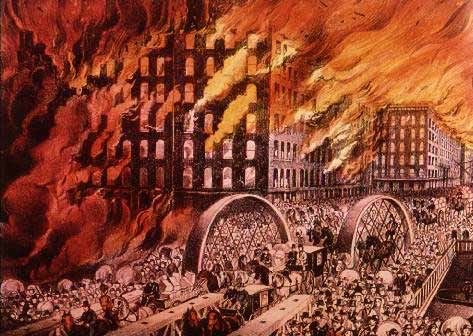

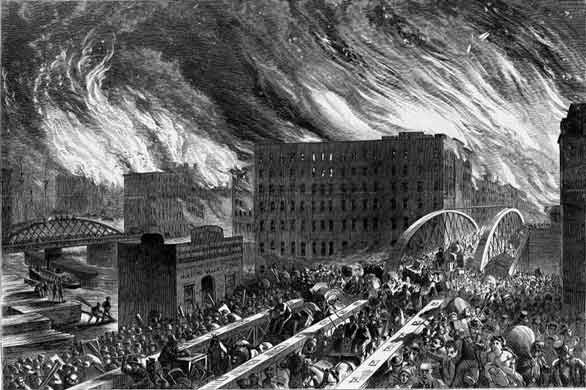

When the fire engulfed a tall church west of the Chicago River, the flames crossed the south branch of the Chicago River. Helping the fire spread were firewood in the closely packed wooden buildings, ships lining the river, the city's elevated wood-plank sidewalks and roads, and the commercial lumber and coal yards along the river. The size of the blaze generated extremely strong winds and heat, which ignited rooftops far ahead of the actual flames.

The attempts to stop the fire were unsuccessful. The mayor had even called surrounding cities for help, but by that point the fire was simply too large to contain. When the fire destroyed the waterworks, just north of the Chicago River, the city's water supply was cut off, and the firefighters were forced to give up.

As the fire raged through the central business district, it destroyed hotels, department stores, Chicago's City Hall, the opera house and theaters, churches and printing plants. The fire continued spreading northward, driving fleeing residents across bridges on the Chicago River. There was mass panic as the blaze jumped the river's north branch and continued burning through homes and mansions on the city's north side. Residents fled into Lincoln Park and to the shores of Lake Michigan, where thousands sought refuge from the flames.

The fire finally burned itself out, aided by diminishing winds and a light drizzle that began falling late on Monday night. From its origin at the O'Leary property, it had burned a path of nearly complete destruction of some 34 blocks to Fullerton Avenue on the north side.

Once the fire had ended, the smoldering remains were still too hot for a survey of the damage to be completed for days. Eventually it was determined that the fire destroyed an area about four miles (6 km) long and averaging 3/4 mile (1 km) wide, encompassing more than 2,000 acres (8 km²). Destroyed were more than 73 miles (120 km) of roads, 120 miles (190 km) of sidewalk, 2,000 lampposts, 17,500 buildings, and $222 million in property - about a third of the city's valuation. Of the 300,000 inhabitants, 90,000 were left homeless. The fire was said by local newspapers to have been so fierce that it surpassed the damage done by Napoleon's siege of Moscow in 1812. Remarkably, some buildings did survive the fire, such as the then-new Chicago Water Tower, which remains today as an unofficial memorial to the fire's destructive power. It was one of just five public buildings and one ordinary bungalow spared by the flames within the disaster zone. The O'Leary home and Holy Family Church, the Roman Catholic congregation of the O'Leary family, were both saved by shifts in the wind direction that kept them outside the burnt district.

After the fire, 125 bodies were recovered. Final estimates of the fatalities ranged from 200-300, considered a small number for such a large fire. In later years, other disasters in the city would claim more lives: 571 died in the Iroquois Theater fire in 1903; and, in 1915, 835 died in the sinking of the Eastland excursion boat in the Chicago River. Yet the Great Chicago Fire remains Chicago's most well-known disaster, for the magnitude of the destruction and the city's subsequent recovery and growth.

Land speculators, such as Gurdon Saltonstall Hubbard, and business owners quickly set about rebuilding the city. Donations of money, food, clothing and furnishings arrived quickly from across the nation. The first load of lumber for rebuilding was delivered the day the last burning building was extinguished. Only 22 years later, Chicago hosted more than 21 million visitors during the World's Columbian Exposition. Another example of Chicago's rebirth from the Great Fire ashes is the now famed Palmer House hotel. The original building burned to the ground in the fire just 13 days after its grand opening. Without hesitating, Potter Palmer secured a loan and rebuilt the hotel in a lot across the street from the original, proclaiming it to be "The World's First Fireproof Building".

In 1956, the remaining structures on the original O'Leary property were torn down for construction of the Chicago Fire Academy, a training facility for Chicago firefighters located at 558 W. DeKoven Street. A bronze sculpture of stylized flames entitled Pillar of Fire by sculptor Egon Weiner was erected on the point of origin in 1961.[2]

Questioning the fire

Catherine O'Leary was the perfect scapegoat: she was a woman, immigrant, and Catholic-–a combination which did not fare well in the political climate of the time in Chicago. This story was circulating in Chicago even before the flames had died out and was noted in the Chicago Tribune's first post-fire issue. However, Michael Ahern, the reporter that came with the story would retract it in 1893, admitting that it was fabricated.[3]

More recently, amateur historian Richard Bales has come to believe it was actually started when Daniel "Pegleg" Sullivan, who first reported the fire, ignited some hay in the barn while trying to steal some milk. However, evidence recently reported in the Chicago Tribune by Anthony DeBartolo suggests Louis M. Cohn may have started the fire during a craps game. Cohn may also have admitted to starting the fire in a lost will, according to Alan Wykes in his 1964 book The Complete Illustrated Guide to Gambling.

An alternative theory, first suggested in 1882, is that the Great Chicago Fire was caused by a meteor shower. At a 2004 conference of the Aerospace Corporation and the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, engineer and physicist Robert Wood suggested that the fire began when Biela's Comet broke up over the Midwest and rained down below. That four large fires took place, all on the same day, all on the shores of Lake Michigan (see Related Events), suggests a common root cause. Eyewitnesses reported sighting spontaneous ignitions, lack of smoke, "balls of fire" falling from the sky, and blue flames. According to Wood, these accounts suggest that the fires were caused by the methane that is commonly found in comets.[citation needed]

Another possible explanation for the coincident conflagrations is that winds associated with the approach of a low-pressure weather system promoted the spread of fires in an area that was tinder-dry due to a prolonged drought.

The Great Chicago Fire and the Web of Memory

http://www.chicagohs.org/fire/

Did a Comet Cause the 1871 Great Chicago Fire?

http://www.mysteriesmagazine.com/articles/issue9.html

Maps: Chicago On Fire

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/chicago/maps/index.html

Great Chicago Fire of 1871

http://chicago.about.com/cs/history/a/04_history_fire.htm

The complete text of James Goodsell's History of the Great Chicago Fire, October 8, 9, and 10, 1871. Published 1871 by J.H. and C.M. Goodsell. (25 pages, including a map of the area affected by the fire.)

In Old Chicago

Site of the Origin of the Chicago Fire of 1871

http://www.ci.chi.il.us/Landmarks/S/SiteChicagoFire.html

Urban Disorder and the Shape of Belief

The Great Chicago Fire, the Haymarket Bomb, and the Model Town of Pullman

http://www.press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/764176.html

The Fire and Cultural Memory

No matter what anyone thought the fire meant, for good or ill, everybody agreed that it marked a moment of major transition in Chicago history. James W. Milner told a friend less than a week after the event, "an age has closed, and a new epoch…is about to begin." This "new epoch," Milner added ominously, is "obscured in doubt and uncertainty." The following day Cassius Milton Wicker wrote to his family, "Everything will date from the great fire now." Four decades later, Frederick Francis Cook confirmed their predictions in his memoir, Bygone Days in Chicago: "As in our national life the old regime is divided from the new by the Civil War of 1861," he explained, "so in the minds of Chicagoans the city's past is demarcated from the present by the great fire of 1871. In respect to both it is a case of 'before' or 'after.'" The local population seized upon the disaster as an historical marker that would help them frame and understand urban experience and this period of rapid change in terms of the fire's own unpredictable and dramatic, violent and destructive, decisive and irreversible qualities.

Of Time and the Fire

As time passed, there were those who looked back on the fire wistfully. For some individuals, including a few of the old settlers, it became the focus of their nostalgic yearnings for a better day that could never be reclaimed. Writing near the turn of the century, the aged Mary Ann Hubbard complained, "Chicago was a much pleasanter place to live in then [during the antebellum period] than it is now, or has been since 'The Fire.' The people with whom we associated were all friendly and kind, sharing each other's joys and sorrows, and enjoying simple pleasures. The Sabbath was kept holy, and the people were mostly such as we wished to associate with." To Mrs. Hubbard, as to so many older people in all times and places, the best was what had been, not what would be, and what others called progress was a regrettable decline. Life was better in the old days because Chicago was a simple and moral human community that did not have the kind of people "we" didn't like, or at least "they" were not so obtrusive. The implication was that these people somehow came with the fire or the fire forced "us" to live with "them," with unhappy and unpleasant results.

Some of this nostalgia, expressed with more subtlety, was in the earliest accounts of the fire. A description of the destruction of the North Division residence of the Isaac N. Arnold family, which appeared in the Evening Post and was reprinted in several other newspapers and fire histories, expressed a longing for a finer world now beyond recapture. The gracious Arnold home took up the entire block bordered by Erie, Huron, Rush, and Pine (now Michigan Avenue) Streets, and it contained a library of eight thousand history, literature, and law books, as well as a Lincoln and Civil War collection that was one of the much-mourned cultural casualties of the fire. The house was also well known for its lush and varied landscaping. The different versions of the account lavish attention on the lilacs, elms, barn, and greenhouse that were trappings of a settled village life, already under siege before the fire, that would no longer be possible in the rebuilt modern city.

The fire signaled the passing of this old order through its destruction of two emblems of that world in the Arnold garden. The first was the "simple but quaint fountain ... beneath a perfect bower of overhanging vines." The fountain was fashioned from a large boulder that featured a rudely carved face of an Indian chief from an earlier era in Chicago history. The second was a nearby sundial with the Latin inscription, Horas non numero nisi serenas ("I reckon only fair hours"), which "was broken by the heat or in the melee which accompanied the fire," so that "the dark hours which have followed pass by without its reckoning." Gone from Chicago was its former harmonious relationship with domesticated nature represented by the fountain, the "perfect bower," and the happy inscription. The accounts of the loss of this little Eden seemed to sense that post-fire Chicago would have other uses for precious real estate than rambling grounds and bowers, and that it would follow the frenetic man-made pace of the time clock, not the sundial.

The predominant view of the fire, however, was decidedly forward-looking and optimistic. As if it were theirs by right, Chicago's boosters claimed possession of the official public memory of the fire, which they dedicated entirely to the golden future, downplaying much of the earlier talk of piety, character, efficiency, and culture. They continued to declare to all that the destruction of Chicago was the best thing that ever happened to the city. Chicago Board of Trade secretary Charles Randolph quickly picked up the booster flag from John S. Wright in proclaiming that God, geography, and history were on Chicago's side. "Nature has seemed to especially designate the banks of the little bayou on which man has built Chicago as a proper and necessary place for the exchange of commodities," Randolph declared. While "some may find their burden greater than they can ever stagger under," he contended, others, "with the aid of the outstretched helping hands from the four quarters of the globe," would "repair the waste places, rebuild the levelled landmarks, and raise from the ashes of Chicago past, a city more grand, more substantial, and in every way more adapted to the needs of what the world has come to recognize as the necessities of Chicago future." In this statement, grandeur and substance unseated simplicity and quaintness as desirable urban values, all under the iron rule of "necessity," whose more appealing synonym was "progress."

Another commentator, who clearly saw the city's future through the eyes of the Yankee elite, proclaimed that Chicago's recovery was not only "the proudest manifestation of the concentration of all Anglo-Saxon energy and enterprise, but also …the shining type of the progress of the Nineteenth century." He went on to assert that the fire surpassed the Franco-Prussian War as an event of significance, creating as it did "a new starting point for the memories of the rising generation." The fire was certainly the starting point in the cultural memory of modern Chicago, which adapted history to its own needs and purposes. The greatest imaginative feat of remembering was to claim that the epic disaster at once gave the young city what it most lacked—a history and a tradition—and devalued the past. This involved a paradox that required a good deal of evasion and repression. The paradox was based in the much-repeated notion that the scale of the disaster demonstrated the greatness of Chicago, which earned recognition as a world-class city by burning to the ground. W. W. Everts, the most prominent Baptist minister in Chicago, took as his text for his sermon, "The Lord thy God turned the curse into a blessing unto thee, because the Lord thy God loved thee," and then told the story of a Chicago businessman traveling in Switzerland before the fire who came upon a map of the United States that marked the location of Milwaukee but not Chicago. Everts then asked his congregation if they thought this could ever happen now. "Do you think another map will be published on this globe without Chicago? Do you think that there will be any intelligent man who will not know about Chicago?" The answer was obvious. "Oh no!" As was the lesson: "Then if material progress be a blessing at all, you see what a distinction has been brought about by the fire." The disaster literally put Chicago on the map by wiping it out.

The fire had thus bestowed on the city a portentous moment of origin that involved the obliteration of its actual past and the directing of all energy and attention toward Chicago's prospects in a modern social and economic order. The catastrophe, instead of shutting down its future, encouraged the destruction of its memory of its pre-fire history as surely as it burned the records in the Courthouse, the artifacts in the Historical Society, and the precious books in Isaac N. Arnold's library. While several of the fire histories included a chronicle of Chicago from the Indian settlements through the Civil War, they also emphasized how completely this earlier era was burned away, and was now dead, distant, and irrelevant. For many, Chicago's past was all condensed into this fiery moment out of which its glorious future was born. This idea was reinforced by boosters, above all the "rising generation" of business leaders, and accepted without reflection by the continuing flow of immigrants from the rest of the country and the world who had no imaginative association with the Chicago that was. They would all start anew in a fresh context full of great expectations. The final paradox was that the first task of cultural memory would be to forget.

• • •

A completely successful escape into boosterism and spectacle was not possible, however. There could be no instant reprieve from the anxieties about Chicago society and culture expressed in the fire literature, even by some imagined moral economy in which a second chance was somehow "paid for" through the suffering caused by the appalling calamity. There was in the boosterism a desperate kind of wishful thinking, a desire to escape the conflicts of historical experience and avoid the difficulties of the present by embracing the future, where nothing has yet happened and so the possibilities are without limit. Some of the less reassuring messages of the fire about the nature of that future were inescapable, however. In a country as varied, complex, and interdependent as that which contained places like Chicago, it sometimes seemed as if a whole city or nation could be put seriously at risk by the actions of almost anyone. The larger moral of Mrs. O'Leary was not so much that it was dangerous to admit these Irish immigrants into "our" midst. Indeed, they were among the most important groups in the building and the rebuilding of Chicago, whether the native-born elite liked it or not. These people would have to be dealt with, since they were part of the system.

The most important lesson of the unhappy accident in the barn was that urban order was so vulnerable that, in the words of a popular song, a cow could kick over Chicago, setting off a night of horrors locally and threatening to bring down the whole system of modernity in which the city had assumed so important a position. The public mood could be skittish and brittle, and any bad news, feeding on fear and anxiety, could have large consequences near and far. Inside Chicago, the rumors of thieves and incendiaries led the city to the assumption of special powers by the Relief and Aid Society and the United States Army. Beyond, the burning of Chicago caused financial havoc. Remarking on the collapse of stock prices following the fire, the Nation attributed this to "the keen scent of Wall Street," which "discovered the gravity of the evil at an early hour," with the result that "the owners of railroad securities so long upheld by the manipulations of gigantic rings and combinations, eagerly rushed into the market as sellers, producing a panic and excitement almost equal in intensity to that of the famous Black Friday of 1869."

New York's instant access to information about Chicago, which enabled it to ship relief supplies while the city was still ablaze, thus set off a secondary calamity of sorts. The would-be safety net of national commerce in which Chicago was a vital element was also a precarious economic web made up of an overextended banking system, great corporations "under the control of reckless Wall street gamblers," inflated real estate, national finances "in a nebulous state of transition," and confused political institutions. "[W]ith all these unfavorable circumstances pressing on the community," the Nation explained, "the destruction of so large an amount of property at Chicago has a most disastrous effect, and tends to destroy credit in every direction, and to precipitate a panic." The fire seemed to have revealed rather than caused the chaotic financial condition of the country, and the commotion on the trading floor reproduced the situation in the streets.

The overall effect of the burning of Chicago on business, the article continued, "is perhaps as striking a proof as we have ever had of the closeness of the relations which have been established between the uttermost ends of the earth. Calamities, and especially great calamities, are fast ceasing to be what is called local—they are now all general." Referring to the aroused feeling which was the central subject of the sentimental tributes to the relief effort, the Nation insisted on practical truth: "No serious disaster can overtake Chicago or St. Louis without making London feel something more than sympathy." That something was the uneasy recognition that in the modern age of cities there was no such thing as an isolated catastrophe. "It appears almost probable," the article went on, "that there will, before long, be no privileged places any more than privileged persons, and no place, in short, any more peaceful or secure against alarms and anxieties than any other place." The sobering conclusion: "The Happy Valley is a thing of the past."

There were a number of important realizations wrapped up in these thoughts. The fire had perhaps put Chicago on the map as a major city, but it also served notice that the dangers of modern life went a good deal beyond those posed by bad building techniques. Tomorrow promised more trouble, not liberation or redemption from the restrictions and sins of the past, but additional entanglements, complications, and conflicts. In its scope, suddenness, and destructive power, the fire spoke of the scale, mystery, instability, and uncertainty of urban life. In its indescribability it offered an unsettling way of perceiving the world it consumed. The fire had, among other things, rearranged and intensified the old categories for understanding the nature of experience. It offered actual events "more romantic than the veriest fiction," Frank Luzerne warned his readers, events whose "realities" could "only be written as it was, with a pen of fire." Chicago's calamity seemed to force a shift in thinking about the new reality the fire appeared to create and reveal. Luzerne repeatedly employed the term "reality," as well as several closely related words. He maintained that his account dealt "with realities alone," but that "it was almost impossible for the compiler to divest his mind of the impression that he is recording a horrid phantasmagorical vision, rather than the facts of real life," and that if Luzerne failed in being true to the realities of his subject, it would be in not being "phantasmagorical" enough. The Chicago Times likewise spoke of the "terrible reality of the scene," while the New York Sun remarked that the eyewitness reports it published "seemed like an overwrought tale of fiction rather than the grim and terrible reality that all knew it to be."

In this period of so many transitions and conflicts, including the contention between the romantic and the realistic imagination as the most valid interpreter of experience, reality was here linked to "overwrought" fiction, and to terror, and beyond that to the central image of a proud young city on fire, which became in turn the representation of a new and unsettling actuality. The dominant imaginative interpretive view of the fire was based on the ideas of resurrection, purification, revival, and renewal, but not without the very real possibility of catastrophic destruction of a world which contained within itself the elements that could undo it. As powerful and even as justified as was the booster dream, it could not dispel this fear, which the fire literature imagined as the fair city in distress at the hands of incendiaries and demons who would defame, defile, and destroy her unless good citizens were vigilant and forceful. All too soon the ritualized hanging of the enemy of the people would move from dark fantasy to real event and occupy center stage in the public imagination. The most terrible reality of the fire was that the unspeakable and the indescribable had happened, furnishing a vocabulary and a conceptual framework for a troubled future.

Catherine O'Leary

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catherine_O%27Leary

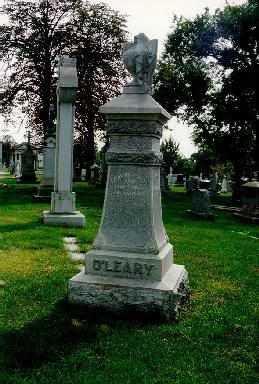

Catherine O'Leary (also known as Cate O'Leary) (ca. 1827 - July 3, 1895) was an Irish immigrant living in Chicago, Illinois in the 1870s. It was alleged that on the evening of October 8, 1871, a fire started in her barn at 137 DeKoven Street which went on to burn a large percentage of the city, an event known as the Great Chicago Fire. She was married to Patrick O'Leary. The couple's son, James Patrick O'Leary would grow up to run a Chicago gambling hall.

After the Great Chicago Fire, she was used as a scapegoat by Chicago Tribune reporter Michael Ahern, who admitted in 1893 that he had made up the story of a cow kicking over a lantern because he thought it would make colorful copy. This story took the population's imagination and many still believe that the fire began with the O'Learys' cow knocking over a lantern. More recent theories posit that Daniel "Pegleg" Sullivan or Louis M. Cohn, who may have been gambling in the barn with the O'Leary's son, James, were involved in the start of the fire.

However, the story of Mrs. O'Leary's Cow has garnered the attention and imagination of generations as the cause of the fire. Popular culture, such as Gary Larson's cartoon The Far Side or Brian Wilson's song "Mrs. O'Leary's Cow," have referred to the story with the expectation that the populace will understand the reference.

Years later, people would sing a parody to the minstrel song There'll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight[1]:

Late one night, when we were all in bed,

Old Mother Leary left a lantern in the shed;

And when the cow kicked it over, she winked her eye and said,

"There’ll be a hot time in the old town, tonight."

Catherine O'Leary died on July 3, 1895 of acute pneumonia at her home at 5133 Halsted Street and was buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery. In the PBS documentary, Chicago: City of the Century, a descendant of O'Leary stated that she spent the rest of her life in the public eye, in which she was constantly blamed for starting the fire. Overcome with much sadness and regret, she "died heartbroken".

Late one night, when we were all in bed,

Mrs. O'Leary lit a lantern in the shed.

Her cow kicked it over,

Then winked her eye and said,

"There'll be a hot time in the old town tonight!"

http://www.chicagohistory.org/fire/oleary/

Did Mrs. O'Leary's cow start the Great Chicago Fire?

There's evidence that suggests she did. The conflagration almost surely began in the vicinity of the crowded family barn, where, in addition to a horse, a calf, and a wagon, Kate O'Leary kept the five cows she milked twice a day for her local dairy business. The O'Learys had just laid up plenty of coal, wood shavings, and hay to see them and their livestock through the winter--and to feed any fire once it got going. Kate supposedly revealed to different people the morning after the blaze began that she was in the barn when one of her cows kicked over a lantern. A few curiosity-seekers claimed to find the broken pieces of such a lantern while snooping behind her cottage, whose survival was one of the great ironies of the disaster.

But one can find good reason to think that poor Mrs. O'Leary and her benighted cow--named Daisy, Madeline, and Gwendolyn in assorted retellings--were innocent. There's testimony to corroborate Kate's contention that she was in bed early that evening, and the official inquiry found no proof of her guilt. Those who heard her "confess" offered different reasons why she said she was in the barn, and a person who years later said that as a boy he found the broken lamp under some floorboards and took it home never explained why the barn had floorboards at all or how they made it through the inferno. As for the lamp itself, he said that he couldn't produce it because an Irish servant, as part of a cover-up, "borrowed" it and then disappeared.

On top of this, on the fortieth anniversary of the great conflagration a police reporter named Michael Ahern, who was working for the Chicago Republican at the time of the fire, boasted in the Tribune that he and two now-deceased cronies made the whole thing up. The O'Leary's, he reminded readers, lived in the rear of 137 DeKoven, renting the front to a family named McLaughlin, who were hosting a party that evening. Ahern opined that one of the revelers went out to get milk for some punch and ended up burning Chicago down. To make the mystery murkier, the invention of the cow story has also been attributed to others, and after Ahern's revelation appeared a long-time colleague wrote to members of the O'Leary family telling them that he had ghost-written the Tribune story under Ahern's byline. As for Ahern himself, this other reporter confided, "The booze got him many years ago, and he has not been able to do any newspaper work."

Several additional theories surfaced then and since. Some boys were sneaking a smoke. Spontaneous combustion. A fiery meteor that split into pieces as it fell to earth October 8, which explains the simultaneous catastrophes in Chicago and Peshtigo, Wisconsin, plus a lesser fire in Michigan. Daisy acted alone. Recently a researcher, working from property records and the post-fire inquiry, has argued that an O'Leary neighbor may have accidentally sparked the blaze.

Like the several cowbells that different people have sworn were the one the four-legged perpetrator (who herself perished in the fire) wore around her neck that fateful night, it is possible that any one of these theories has the truth behind it, but all of them are open to question.

In any case, the more intriguing issue is not the unresolvable one of whether the legend has any basis in fact, but why it has had so much continuing interest, why to the present day the story of Mrs. O'Leary's cow is above all others the one "fact" that almost everyone near and far recalls about the Great Fire, and, for that matter, about the history of Chicago.

The O'Leary story, true or not, has had such appeal because it offers a clear and specific cause for this otherwise overwhelming event, an imaginative handle by which people can take hold of it. Regardless of the inconclusiveness of the official investigation, at the time it also enabled people to blame someone in particular for what was a matter of collective responsibility and misfortune. In this respect it is noteworthy that the O'Leary legend found brief competition with a rumor that the fire was set by an unnamed member of a world-wide terrorist organization with direct ties to the 1871 Paris Commune. A local paper even published his "confession," and a poem that appeared in the New York Evening Post wondered out loud:

Did out of [Paris's] ashes arise

This bird with a flaming crest,

That over the ocean unhindered flies,

With a scourge for the Queen of the West?

But Mrs. O'Leary offered a far better scapegoat. While as a specific person she may or may not have been at fault, what she represented was a more plausible and acceptable cause for the fire. Unlike the Communard, she was a familiar and recognizable type who could readily be made to stand for careless building, sloppy conduct, and a shiftless immigrant underclass. Blaming her simply involved adapting existing anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant sentiments to the terrible calamity at hand. As a poor clumsy Irishwoman and not a sworn enemy of the social order, she was a disempowered comic stereotype, the damage she caused the result of accident, not conspiracy. Given that the catastrophe could not be undone, there was even something imaginatively satisfying in the tale that this epic fire had such a humble beginning.

The lasting nature of the O'Leary legend is attributable to the fact that she also was such a malleable figure, who could be used to discover and express different and even conflicting meanings. From the outset, people were interested not in knowing the real Catherine O'Leary, but in turning her into a repository for their presuppositions. She was in her early forties at the time of the fire, sober and hard-working. In some popular anecdotes and illustrations she was depicted as an aged crone and a drunkard. The Chicago Times, while not naming her specifically nor accusing her of setting the fire deliberately, described her as a welfare cheat who, "when cut off, vowed revenge." But as it became clear that the city had fully triumphed over catastrophe and was hurtling on to an even grander destiny, she became increasingly quaint and benign. In 1881 the Chicago Historical Society installed a marble plaque marking the spot on the much more solid home that had been built at 137 DeKoven. The alley behind the house became a kind of sacred site for local residents, who protested when the city finally filled it in and paved it two decades after the great conflagration. And when Chicago constructed a new fire academy in the early 1960s, it selected as the location the block where the calamity began.

Perhaps the most remarkable and fanciful reworking of the O'Leary legend was the 1938 movie, In Old Chicago. Kate O'Leary (played by Alice Brady, who won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress) is aged a decade or two and divested of her husband, as she is transformed into the spirited widow Molly O'Leary, who runs a successful hand laundry that caters to Chicago's fancy set. To her dismay, her son Dion (Tyrone Power) becomes an unprincipled saloon owner, but his brother Jack (Don Ameche) is an idealistic lawyer who is elected mayor on a reform platform. The centerpiece of his program is to level the firetrap neighborhoods in "the Patch" (evidently based on Conley's Patch) controlled by gamblers and political operators like his brother. Jack sacrifices his life for the city when, while he is trying to stop the fire, he is first shot by a corrupt political opponent and then crushed by a collapsing building.

Hearing this sad news from a now morally awakened Dion as they find refuge in the lake, Molly proudly rededicates the family to the building of a new and better Chicago. The unsinkable Molly is reconciled to Jack's death by her faith in a still greater future to come. For his part, Dion exultantly declares, "Nothing can lick Chicago." In this narrative with plot conventions shared with a long list of disaster stories (including Roe's Barriers Burned Away and MGM's disaster epic, San Francisco) Hollywood thus turned once-despised immigrants like the O'Learys into upwardly mobile middle-class champions of the Chicago booster dream. One glancing coincidence between actual events and this narrative that takes such vast liberties is that the O'Learys did have a son named Jim, who well after the fire was a politically connected saloon keeper and gambler in the stockyards district.

In Old Chicago does pin the fire's origin on Daisy, who does her dirty work when she is left alone for a moment by a distracted Molly. But this is almost incidental to the main plot, and there's no particular blame assigned. By this time the legend was a charming mainstay of American folklore, the subject of a Norman Rockwell painting. Various local parades, commemorations, and promotions would feature a woman dressed up as Mrs. O'Leary leading Daisy. The winner of the National Trophy in the 1960 Rose Bowl Parade, whose grand marshal was Vice President Richard Nixon, was the City of Chicago float depicting Mrs. O'Leary's barn, complete with a lantern, simulated fire, genuine smoke, and a carnation-and-chrysanthemum cow. The theme of the parade was "Tall Tales and True."

Kate O'Leary, unfortunately, never got to enjoy any of this. She bemoaned her own losses by the fire, which included all the animals in the barn except the calf, but otherwise she tried to avoid the unwanted attention, including offers from promoters. She and her family moved to a series of homes around 50th and Halsted, where journalists would seek her out for interviews in early October. She would ignore them or chase them away, and they in turn would make up stories that revived the old stereotypes about the unwashed poor. In 1886, for example, a Daily News reporter whom she supposedly rebuffed described her home as follows: "The house has no front door, in lieu of glass clothing is stuffed into two or three windows, and long before a stranger reaches the place the pungent odor of distillery swill and the effluvium of cows proclaim that old habits are strong with Mrs. O'Leary and that she is still in the milk business." Patrick O'Leary died in September of 1894, and Catherine passed away the following Fourth of July.

Prevention message traces back to Chicago fire

Massive 1871 blaze that killed over 250 and left 100,000 homeless prompted creation of Fire Prevention Week

http://www.canada.com/deltaoptimist/news/story.html?id=f2a57415-ed8f-49d9-a8b0-ef1fd742359f

Fire Prevention Week was established to commemorate the Great Chicago Fire, the tragic 1871 conflagration that killed more than 250 people, left 100,000 homeless, destroyed more than 17,400 structures and burned more than 2,000 acres.

The fire began on Oct. 8, but continued into and did most of its damage on Oct. 9, 1871.

According to popular legend, the fire broke out after a cow, belonging to Mrs. Catherine O'Leary, kicked over a lamp, setting the barn, then the whole city, on fire.

Chances are you've heard some version of this story yourself; people have been blaming the Great Chicago Fire on the cow and Mrs. O'Leary for more than 130 years. But recent research by Chicago historian Robert Cromie has helped to debunk this version of events.

Like any good story, there is some truth to it. The great fire almost certainly started near the barn where Mrs. O'Leary kept her five milking cows. But there is no proof O'Leary was in the barn when the fire broke out -- or that a jumpy cow sparked the blaze. O'Leary swore she'd been in bed early that night, and the cows were also tucked in for the evening.

But if a cow wasn't to blame for the huge fire, what was? Over the years, journalists and historians have offered plenty of theories. Some blamed the blaze on a couple of neighbourhood boys who were near the barn sneaking cigarettes. Others believed a neighbour might have started the fire. Some people have even speculated that a fiery meteorite may have fallen to earth, starting several fires that day -- in Michigan and Wisconsin as well as in Chicago.

While the Great Chicago Fire was the best-known blaze to start during this fiery two-day stretch, it wasn't the biggest. That distinction goes to the Peshtigo Fire, the most devastating forest fire in American history.

The fire, which also occurred on Oct. 8, 1871, roared through northeast Wisconsin, burning down 16 towns, killing 1,152 people and scorching 1.2 million acres before it ended.

Historical accounts say the blaze began when several railroad workers clearing land for tracks unintentionally started a brush fire. Before long, the fast-moving flames were whipping through the area like a tornado, some survivors said. It was the small town of Peshtigo, Wisconsin that suffered the worst damage. Within an hour, the entire town had been destroyed.

Those who survived the Chicago and Peshtigo fires never forgot what they'd been through; both blazes produced countless tales of bravery and heroism. But the fires also changed the way that firefighters and public officials thought about fire safety.

On the 40th anniversary of the Great Chicago Fire, the Fire Marshals Association of North America (today known as the International Fire Marshals Association) decided the anniversary of the Great Chicago Fire should be observed not with festivities, but in a way that would keep the public informed about the importance of fire prevention.

The commemoration grew incrementally official over the years.

In 1920, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson issued the first National Fire Prevention Day proclamation, and since 1922, Fire Prevention Week has been observed on the Sunday through Saturday period in which Oct. 9 falls.

Mark fire safety week by following these tips

http://www.app.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20071009/LIFE/710090344/1006/LIFE

In 2006, fire killed more Americans than all natural disasters combined. Home fires were the leading cause of fire deaths, with 80 percent of all fire-related fatalities occurring as a result of residential fires.

To mark Fire Prevention Week, which runs through Saturday, First Alert and Mr. Handyman International offer these tips to reduce the risk of fire-related injury and property loss:

Keep matches and lighters out of sight and reach of children.

Never leave a candle unattended and keep flames at least three feet away from curtains, furniture or other flammable materials.

Discard frayed or cracked electrical cords.

Clean your dryer vent annually.

Create and practice a home escape plan at least twice a year, making sure everyone is involved.

Install smoke alarms with both photoelectric and ionization sensing technologies on every level of your home for maximum protection.

Have a smoke alarm in every bedroom and on every level of the home.

Test smoke alarms at least once a week.

Change the batteries in smoke alarms every six months or when the low battery signal is heard.

Never remove a battery or disarm a smoke alarm.

Make sure everyone in your home knows the sound of the smoke alarm, what to do next and that the alarm is loud enough to wake up sleeping children and adults.

Keep a fire extinguisher or fire extinguishing spray in your kitchen and near other areas where a fire could occur, such as in a workshop, garage or near a fireplace.

No matter how small the fire, if you can't extinguish it immediately, get out!

Identify two safe ways out of every room in the house, especially upstairs. Draw these exits on a map and place a copy in every room.

Practice fire escape drills twice a year. Have everyone practice escaping every room in the house and practice crawling low under smoke.

Pick an outside meeting place where everyone can gather after they've escaped. Remember to mark this spot on your fire escape map.

Keep doors, stairways and other exits clear of toys, furniture and other clutter.

Close the door behind you. This will slow the spread of fire and smoke.

National Fire Prevention Week (NFPW) always falls in the week of Oct. 9 to commemorate the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 that killed more than 250 people, left 100,000 homeless, destroyed more than 17,400 structures and burned more than 2,000 acres. Since 1922, Fire Prevention Week has been observed during the second week of October.

![Brotherhood" (2006) [TV-Series]](http://photos1.blogger.com/x/blogger2/1421/379621144723082/211/z/425926/gse_multipart33129.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment