Chernobyl The After effects

Chernobyl Legacy

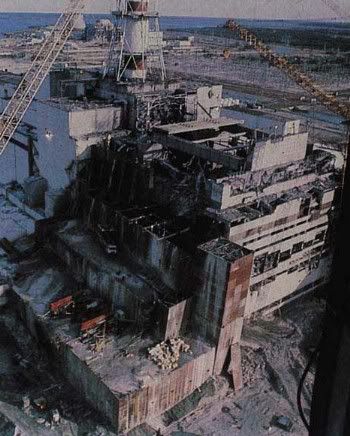

The Chernobyl disaster was a major accident at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant on April 26, 1986 at 01:22 a.m.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chernobyl_disaster

http://www.answers.com/topic/chernobyl

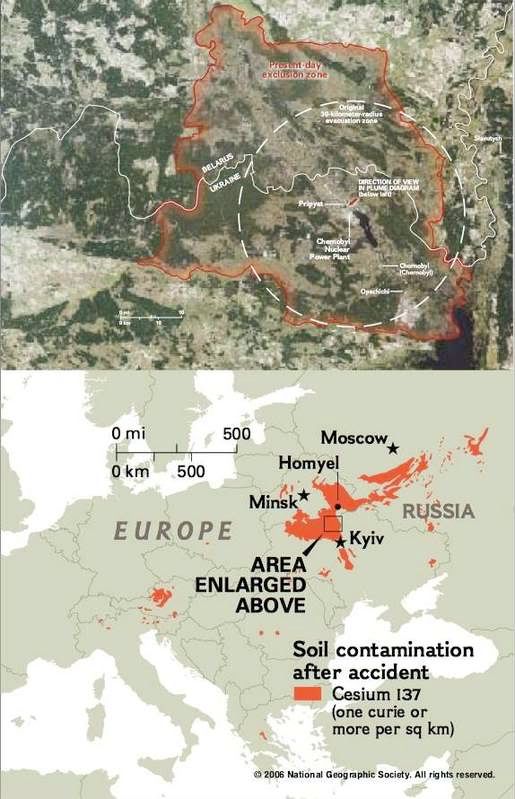

Chernobyl (chuhr-NOH-buhl, cher-NOH-buhl) A place in Ukraine where a nuclear power plant — a generator powered by a nuclear reactor — underwent a meltdown in 1986. A cloud of radioactive gases spread throughout the region of Chernobyl, and to foreign countries as well. Forty thousand people living nearby were evacuated. Dozens of deaths and hundreds of illnesses were reported to have been caused by the accident.

http://www.answers.com/topic/prypiat-ukraine

Prypiat, Ukraine

Prypiat (Ukrainian: При́п'ять, Pryp’iat’; Russian: При́пять, Pripyat; Polish: Prypeć; ) is an abandoned city in the zone of alienation in northern Ukraine, Kiev Oblast, near the border with Belarus. It was home to the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant workers. The city was abandoned in 1986 following the Chernobyl disaster. Its population had been around 50,000.

Twenty Years After Chernobyl 2006

http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,191721,00.html

April 26 marks the 20th anniversary of the accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. Anti-nuclear activists are still trying to turn Chernobyl into a bigger disaster than it really was.

Although the Number Four nuclear reactor at Chernobyl exploded just before dawn on April 26, 1986, Soviet secrecy prevented the world from learning about the accident for days. Once details began to emerge, however, the anti-nuclear scare machine swung into action.

Three days after the accident Greenpeace “scientists” predicted the accident would cause 10,000 people to get cancer over a 20-year period within a 625-mile radius of the plant. Greenpeace also estimated that 2,000 to 4,000 people in Sweden would develop cancer over a 30-year period from the radioactive fallout.

At the same time, Helen Caldicott, president emeritus of the anti-nuclear Physicians for Social Responsibility, predicted the accident would cause almost 300,000 cancers in 5 to 50 years and cause almost 1 million people either to be rendered sterile or mentally retarded, or to develop radiation sickness, menstrual problems and other health problems.

University of California-Berkeley medical physicist and nuclear power critic Dr. John Gofman made the most dire forecast. He predicted at an American Chemical Society meeting that the Chernobyl accident would cause 1 million cancers worldwide, half of them fatal.

But the reality of the health consequences of the Chernobyl accident seems to be quite different than predicted by the anti-nuke crowd.

As of mid-2005, fewer than 50 deaths were attributed to radiation from the accident – that’s according to a report, entitled “Chernobyl’s Legacy: Health Environmental and Socio-Economic Impacts,” produced by an international team of 100 scientists working under the auspices of the United Nations. Almost all of those 50 deaths were rescue workers who were highly exposed to radiation and died within months of the accident.

So far, there have been about 4,000 cases of thyroid cancer, mainly in children. But except for nine deaths, all of those with thyroid cancer have recovered, according to the report.

Despite the UN report, the anti-nuclear mob hasn’t given up on Chernobyl scaremongering.

According to a March 25 report in The Guardian (UK), Greenpeace and others are set to issue a report around the 20th anniversary of the accident claiming that at least 500,000 people may have already died as a result of the accident.

Ukraine's government appears to be on board with the casualty inflation game, perhaps looking for more international aid for the economically-struggling former Soviet republic.

The Guardian article quoted the deputy head of the Ukraine National Commission for Radiation Protection as touting the 500,000-deaths figure. A spokesman for the Ukraine government’s Scientific Center for Radiation Medicine told The Guardian, “We’re overwhelmed by thyroid cancers, leukemias and genetic mutations that are not recorded in the [UN] data and which were practically unknown 20 years ago.”

Putting aside the anti-nuclear movement’s track record of making wild claims and predictions in order advance its political agenda, I put more credence in the UN’s estimates because it squares with what we know about real-life exposures to high levels of radiation.

Among the more than 86,000 survivors of the atomic bomb blasts that ended World War II, for example, “only” about 500 or so “extra” cancers have occurred since 1950. Exposure to high-levels of radiation does increase cancer risk, but only slightly.

There is no doubt that Chernobyl was a disaster, but it was not one of mythical proportions.

Chernobyl and Three Mile Island – the U.S. nuclear plant that accidentally released a small amount radiation in 1979 – are examples of how the anti-nuclear lobby takes every available opportunity to scare the public about nuclear power.

But no one was harmed by the incident at Three Mile Island. The Chernobyl accident can be chalked up to deficiencies in its Soviet-era design and operation. Neither reflect poorly on the track record of safety demonstrated by nuclear power plants designed, built and operated in countries like the U.S., U.K., France and Japan.

It’s quite ironic that while Greenpeace squawks about the need to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases in order to avert the much-dreaded global warming, the group continues spreading fear about greenhouse gas-free nuclear power plants – the only practical alternative to burning fossil fuels for producing electricity.

Apparently, Greenpeace’s solution to our energy problems is simply to turn the lights off – for good.

The lessons of Chernobyl

http://www.fortwayne.com/mld/newssentinel/news/editorial/17143678.htm

By Tatyana Sinitsyna

RIA Novosti

(MCT)

MOSCOW - Ever since the explosion of Unit 4 on April 26, 1986, the word Chernobyl has come to symbolize the worst man-made disaster of the 20th century.

It produced a tremendous radiation emission, human victims, broken lives, severe health problems, huge material losses, great stress, and radioactive contamination of enormous territories.

On the day of the tragedy, the winds took the rising plume of radioactive dust from the banks of the Pripyat River and carried it all over the world. Abnormal radiation levels were registered on tea plantations in the Caucasus Mountains, in California and even in the ice of the Antarctic. Europe was the hardest hit - dust settled in Poland, Bulgaria, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Britain and other countries.

Who was to blame for the disaster? It would seem that this question must have been exhausted by now, but it is being raised over and over again. "What is still unclear? The bodies in charge of nuclear and radiation safety and IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency) experts have drawn their conclusions; the trial was held. There are no grounds to doubt the opinion of serious experts," said Professor Alexander Borovoy from the Kurchatov Institute Russian Research Center, who headed a group of scientists in Chernobyl for many years.

"Journalists are still giving me a hard time, but I do not want to answer this question because it conceals the intention to condemn people who went through hell, those whose bodies and souls were burnt, who died an agonizing death. I have no right to be a judge of my late teachers who gave us nuclear energy and nuclear weapons that have protected us up to this day. Only one question matters for me: Has everything been done to avoid a repetition of Chernobyl? The answer is yes."

In the 21 years since the accident, Chernobyl has been visited by thousands of experts from all over the world. They meticulously uncovered what had happened, conducted studies and drew conclusions together. Nevertheless, there are still people who call everything into doubt. They are engaged in heated debates and keep coming up with new, far-fetched hypotheses.

For instance, they conjure up the image of the KGB, which ostensibly "got scared by perestroika," or they talk about a "nuclear explosion of plutonium," which the plant's personnel were allegedly producing in secret. Sometimes, the disaster has been blamed on an earthquake that for some reason was limited to Unit 4, or even presented as a terrorist attack. The conspiracy theorists discovered some yellow stains that they presented as evidence - traces of explosives. In reality, these stains were left by uranium acid. One version was truly fantastic. Its proponents claimed that a "nearby anti-ballistic-missile facility released large doses of radiation that affected the psyche of the night shift at the nuclear plant."

But everything was much simpler than that. On the eve of the tragedy, at 2:25 p.m. on April 25, a young woman called from Kiev, and demanded in no uncertain terms that the station's personnel should turn Unit 4 back on and put off an experiment that was already under way. The angry girl merely relayed the orders of her bosses. The engineers objected but eventually carried out the instructions. The unit worked for nine hours under dangerous circumstances, and finally exploded in response to the personnel's inadmissible actions.

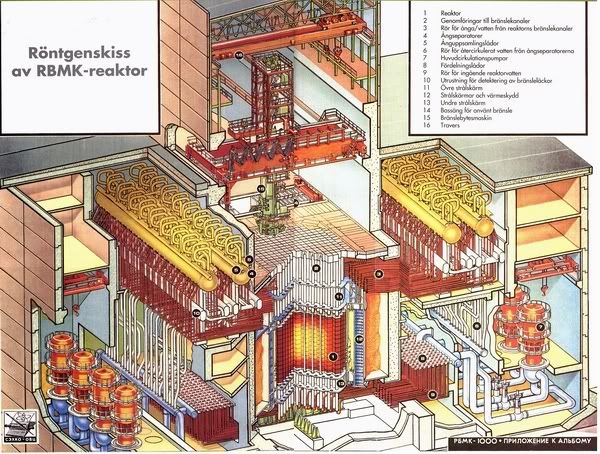

After the disaster, the term "Chernobyl-type reactor" became a synonym for mortal danger and unreliability. It is referred to by its Russian initials, RBMK, which stand for high-power channel-type reactor. One of the leaders of the Russian Green movement, Alexei Yablokov, categorized as insane the government's decision to continue the mothballed construction of an RBMK-type reactor at the Kursk nuclear power station.

But experts maintain that the risk of an accident involving RBMK reactors is truly negligible: 1 million reactor years. "This means that if a reactor worked for the incredibly long period of 1 million years, it might explode by accident. But its average service life is between 30 and 40 years, so in practical terms the probability of an accident is zero," explained Boris Gorbachev, a physicist from Chernobyl.

But the RBMK design still had a weak point: it did not fully consider the human factor and allowed an operator to interfere in its program (the upgraded version rules this out). It was assumed that a nuclear specialist simply could not make a mistake. But, regrettably, neither the director of the station nor the chief operating officer understood the physics of a nuclear plant; they were ordinary specialists in power engineering. Two years before the tragedy, government officials decided to assign nuclear power stations to the Ministry of Electrification; previously they had been part of the nuclear complex. This was the first step on the road to the disaster.

A protective sarcophagus (as high as a 25-story building) was erected over the destroyed unit to contain the radioactive debris. It became a source of increasing concern because of a possible chain reaction - it contained 180 metric tons of radioactive fuel. The shelter was still spewing radiation and builders could not work in its vicinity. As a result, the sarcophagus developed cracks with a total area of about 1,000 square meters through which plutonium dust escaped. The structure of the old sarcophagus was unreliable because it rested on the unit's surviving walls.

It was only 10 years after the disaster that the Chernobyl Shelter Fund was set up to fund the Shelter Implementation Plan. Western countries agreed to cough up the required $1 billion. The new shelter should reliably isolate the nuclear debris for about 100 years. It will be one of the saddest but also one of the most instructive monuments on Earth.

Ukraine President Wants to Renew Chernobyl Area

http://www.ens-newswire.com/ens/apr2007/2007-04-26-06.asp

![Brotherhood" (2006) [TV-Series]](http://photos1.blogger.com/x/blogger2/1421/379621144723082/211/z/425926/gse_multipart33129.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment