http://www.pensacolanewsjournal.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20070330/NEWS01/70330013

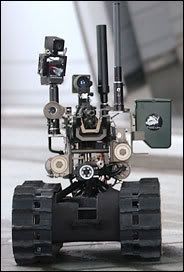

Fido is the first robot with an explosives sensor integrated into its body. iRobot Corp. is filling the military?s first order of 100 in this southwest Ohio city and will begin shipping the robots over the next few months.

There are nearly 5,000 robots in Iraq and Afghanistan, up from about 150 in 2004. Soldiers use them to search caves and buildings for insurgents, detect mines and ferret out roadside and car bombs.

As the war in Iraq enters its fifth year, the federal government is spending more money on military robots and the two major U.S. robot-makers have increased production.

Foster-Miller Inc., of Waltham, Mass., just delivered 1,000 new robots to the military. iRobot, of Burlington, Mass., cranked out 385 robots in 2006, up from 252 in 2005.

The government will spend about $1.7 billion on ground-based military robots between fiscal 2006 and 2012, according to Bill Thomasmeyer, head of the National Center for Defense Robotics, a congressionally funded consortium of 160 companies, universities and government labs. That?s up from $100 million in fiscal 2004.

Fido, produced at a GEM City Manufacturing and Engineering plant, represents an improvement in bomb-detecting military robots, said Col. Terry Griffin, project manager of the Army/Marine Corps Robotic Systems Joint Project Office at Redstone Arsenal, Ala.

The bomb-sniffing sensor is part of the robot, with its readings displayed on the controller along with camera images. Otherwise, a soldier would have to approach the suspect object with a sensor or try to attach it to a robot. The new robot also has a 7-foot manipulator arm so it can use the sensor to scan the inside and undercarriages of vehicles for bombs.

Officials would not release details of how the sensors work because of security concerns.

?The sniffer robot is a very good idea because we need some way of understanding ambiguous situations like abandoned cars or suspicious trash piles without putting soldiers? lives on the line,? said Loren Thompson, defense analyst with the Washington D.C.-based Lexington Institute.

Philip Coyle, senior adviser to the Center for Defense Information in Washington, said the robots could be helpful if they are used in cases where soldiers already suspect a bomb. But he said explosive-sniffing sensors are susceptible to false positives triggered by explosive residues elsewhere in the area, smoke and other contaminants.

?The soldiers can begin to lose faith in them, and they become more trouble than they?re worth,? he said. ?It can slow down things.?

Thompson said all military robots have limitations. Their every move must be dictated by an operator, they can be stopped by barriers or steep grades, they are not highly agile, and they can break down or be damaged, he said.

Robots range in size from tiny ? 1.5 pounds ? to brute ? 110-pound versions that move rubble and lift debris. Fido is an upgrade of PackBot, a 52-pound robot with rubber treads, lights, video cameras that zoom and swivel, obstacle-hurdling flippers and jointed manipulator arms with hand-like grippers designed to disable or destroy bombs. Each costs $165,000.

Army Staff Sgt. Shawn Baker, 26, of Olean, N.Y., has helped detect and disable roadside bombs during two tours in Iraq ? both with and without robots. Before the robots were available, he and fellow soldiers would stand back as far as they could with a rope and drag hooks over the suspect devices in hopes of disarming or detonating them.

?A couple of times you were closer than you needed to be, but it was something you had to do to get it done,? Baker said.

Two soldiers were killed that way, he said. No one in his unit has been hurt or killed while disarming bombs since the robots arrived.

?The science and technology of this has been way out in front of the production side,? Thomasmeyer said. ?We?re going to start to see a payoff for all the science and technology advancements.?

iRobot posted $189 million in sales in 2006, up 33 percent from 2005. Its military business grew 60 percent to about $76 million. Bob Quinn, general manager of Foster-Miller, said his company has contracts of $320 million for military robots and that its business has doubled every year for the past four years.

Griffin, of the Robotic Systems office, said military robots are here to stay.

Unleashing the robots of war

Redstone's robotics chief strives to put technology, not soldiers, in harm's way

By Eric Fleischauer

DAILY Business Writer

eric@decaturdaily.com · 340-2435

http://www.decaturdaily.com/decaturdaily/news/060619/robots.shtml

Many a joke has been told of the military's snail-paced bureaucracy. In Iraq, robotics chief Col. Edward Ward is not laughing.

Ward measures red tape in deaths, and military brass have declined to erect hurdles as Ward marches along the shortest distance between the points.

Based at Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Ward is something of a Decatur fixture due to frequent speeches here, all ginning up support for a robotics program that has proved to be the most effective defense against improvised explosive devices in Iraq.

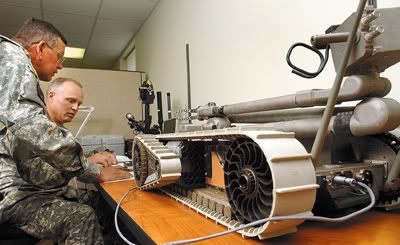

Ward, 50, left the U.S. Marine Corps in 1986. He couldn't stay away. He mobilized in late 2004, becoming head of logistics and business management for Redstone's Joint Project Office on Unmanned Ground Vehicles. It's an example of the "jointness" that is a major goal of today's military. Ward supervises — and is supervised by — Army personnel as well as Marines.

Ward's robots, especially the $7,000 MARCBOT, have become the best friends of explosive ordnance disposal troops.

The radio-controlled vehicle with wheels is 19 inches long. It weighs 25 pounds and has a 24-inch retractable arm with a video camera that sends wireless images to the soldier controlling the unit from more than 100 yards away.

The robot can climb curbs, look inside vehicles or scan ditches. It saves lives.

Ward talks the chain-of-command talk, but his actions show passion for his "kids," not for regulation. When red tape blocks him from producing his lifesaving robots, he pulls out scissors, not a rulebook.

Paul Varian, a civilian robotics expert on his third tour in Iraq, works for Ward. In an e-mail from Baghdad, Varian said Ward's intense focus is not unique in the group of civilians and military troops maintaining and improving anti-IED robots.

"Is Col. Ward driven? Sure," said Varian. "Will some family have a son, daughter, dad or mom come home as a result of a robot taking a catastrophic hit instead of the service member? Yes."

Ward said his intensity goes with the job.

"When you go over there and work with these outstanding young people and see their bravery — see it not sporadically but daily — you want to know how you can help," Ward said last month in his Redstone office, before leaving for his current tour.

"If we can put technology in harm's way and still meet mission, that's important. Then they can come home, undamaged, and live enjoyable lives.

"So yes. I'm focused."

Innovation in uniform

That focus, and the urgency that sparks it, demands innovation. It's a trait not always associated with the military, but Ward takes the shortest distance between two points without disturbing his chain of command. Some examples:

Extending range. Ward recognized that EOD troops had to get too close to IEDs when navigating their robots. He wanted the problem solved in days.

In meetings that more resembled corporate brainstorming sessions than staff meetings between a colonel and his subordinates, Ward prompted his staff for quick fixes. Varian had an idea. A ham-radio enthusiast, Varian recalled that an antenna's strongest signals transmit with the greatest strength not in the direction pointed, but at an angle of 30 degrees.

"Instead of pointing the antenna at the robot, which is what comes naturally, we have them point it 30 degrees away from the robot," Ward recalled. "What did that do? It gave us 300 more meters."

And saved more lives.

Off the shelf. At the core of the military's procurement system are "national stock numbers," basically product identifiers. The NSN system works, but it is slow. Slow means more dead soldiers to Ward.

"We do not conform to Army software or process procedure. I did that for a reason. I want parts to be available commercially, off the shelf. We don't have to go through the system," Ward said.

Which is a good thing, said Varian.

"With NSNs you have to hope someone is stocking the item," Varian said. "With commercial items you just purchase and go."

Ward emphasizes that his innovative approach required approval from superiors.

"Think about it. I'm completely outside the box with our materiel command. These generals and logisticians have been doing this for 20, 30 years. Who am I, a Marine aviator, to come in and say, 'Hey, I wanna do this'? But they've supported us."

Management style. Ward is not the colonel of war movies. He's the boss, but he believes top-down management does not always get the best results.

"He is approachable, he believes in powering down and he encourages folks to act," Varian said. "Col. Ward does not shoot you for making a poor choice. He encourages you to learn, move forward and make a better choice next time. Inactivity will get you more wrath than trying and failing."

Thanks, NASA. Returning IED-damaged robots to the field is a massive job, even though Ward has set up a maintenance facility in Iraq. It's also a time-consuming process because many parts had to be ordered from the United States.

In a military that still balks at the efficiencies of "jointness" — cooperation between services — Ward walked down the street from his Redstone office and knocked on NASA's door. NASA uses robots in places more remote, even, than Iraq.

"They have to be able to make their parts on the moon. FedEx don't go there," Ward chuckled. "Well, if they can make their parts on the moon, I figure we ought to be able to make them in Afghanistan."

More to come on that effort, Ward said.

Using the Web. Ward said written reports to superiors are legitimately important in the military.

"The only problem with reports is, I don't have enough people to do reports," Ward said. "I want my folks doing one thing: fixing robots. Saving lives."

So Ward bid out the creation of a supply management Web site that generates reports whenever his superiors want them, in real time. All without taxing the time of his technicians.

"Speed is life. Now, it doesn't conform with the typical Army standard, so we're kind of out there. Is that good? Yes and no. Yes, because we can make mission and do it faster and cheaper. ... Someday we may have to change, but every day we keep it going like this, we save lives," Ward said. "And who knows? We may be able to influence what the Army's requirements are in the future."

With occasional exceptions, Ward shows no obsessive traits when stateside. He laughs loud, makes fun of himself, teases colleagues and reporters. Until the subject turns to his "kids."

"When I get off the airplane in Kuwait and go to Baghdad," Ward said, "I'm not the same person you see today."

EOD officers' focus on mission is in some respects Ward's curse.

"I promise you that if they don't have a robot to go down-range to look at that trash pile to determine if it's an IED, or to look in that vehicle, they'll go downrange themselves. They do it every day," Ward said.

"These kids put on 100-pound bomb suits on a 140-degree day and walk 300 or 400 or 500 meters down a road, exposed to small-arms fire because every IED is an ambush. And then they confront the IED."

![Brotherhood" (2006) [TV-Series]](http://photos1.blogger.com/x/blogger2/1421/379621144723082/211/z/425926/gse_multipart33129.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment